View sample workers’ health research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a health research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The labor market is a place where labor demand and supply mutually interact in relation to jobs, working conditions, and salaries. Major issues in labor market relations include employment, unemployment, labor market participation rates, and salaries. The secondary labor market, which refers to jobs with poor working conditions (high turnover, low salary, and insecure employment) has intrinsically grown around the world, alongside traditional full-time jobs. A majority of secondary workers, which includes atypical workers, informal jobholders, child laborers, and bonded laborers, are regarded as being exploited as cheap labor sources in developed and developing countries. The poor working environment surrounding these vulnerable groups is related to health risks. The potentially hazardous features of the secondary labor market have raised increasing concern among epidemiologists and health policy makers.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Labor Market Terms

Key Terms In The Labor Market Literature

The labor market is the area where labor supply meets labor demand.

Economically active population refers to persons who are at or above the minimum age for full-time employment and below the state retirement age, who are working or looking for work. A person economically inactive is defined as a person, at or above the minimum age for full-time employment and below the state retirement age, who is neither employed nor looking for work. Economic inactivity is usually due to long-term illness. It is also used to describe those doing full-time unpaid domestic work, early retirees, and a small group of persons who do not want to work.

Demand for labor refers to the number of jobs in an economy of a given nation. Most demand is for a specific skill level. In the 1980s, the demand for both skilled and unskilled industrial labor decreased sharply in developed nations as technology advanced. In the 2000s, it is predicted that the demand for many types of skilled nonmanual labor (clerical, secretarial, data processing) will also decline. However, the demand for unskilled nonindustrial labor (such as that required in catering, home care, and private domestic service) will increase.

Employment is a contract between buyers and suppliers of labor (employer and employee). The employer profits through an employee’s productive activity for the company, and the employee provides labor in exchange for monetary payment. Employment includes all individuals who work at least an hour for a wage, are self-employed, or unpaid family workers. New challenges in the employment relationship have arisen from the growing flexibility and globalization of the employment relation.

Globalization is defined as ‘‘the growing economic interdependence of countries worldwide through increasing volume and variety of cross-border transactions in goods and services, free international capital flows, and more rapid and widespread diffusion of technology’’ by the International Monetary Fund. On the other hand, The International Forum on Globalization (IFG, 2002: 1) defines it as ‘‘the present worldwide drive toward a globalized economic system dominated by supranational corporate trade and banking institutions that are not accountable to democratic processes or national governments’’ (IFG, 2002 p. 1) While notable critical theorists, such as Immanuel Wallerstein, emphasize that globalization cannot be understood separately from the historical development of the capitalist world system, the different definitions highlight the ensuing debate of the roles and relationships of government, corporations, and the individual in maximizing social welfare within the globalization paradigms. Nonetheless, it is clear that globalization has economic, political, cultural, and technological aspects that may be closely intertwined. Given that these aspects are important to an individual’s quality of life and health, the social benefits and costs brought upon them by globalization generate strong debates.

The concept of decent work was first introduced by the International Labour Organization in 1999, defined as ‘‘opportunities for women and men to obtain decent and productive work in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity.’’ Decent work reflects the ILO’s converging focus of four strategic objectives: the promotion of rights at work, employment, social protection, and social dialogue.

Standard employment usually defines what it means to be in full-time, year-round, permanent employment with benefits. However, precarious employment has been used to signal that new employment forms might reduce social security and stability for workers. Flexible, contingent, nonstandard, temporary work contracts do not necessarily provide an inferior status as far as economic welfare is concerned. Precarious work forms are located on a continuum, with the standard of social security provided by a standard (full-time, year-round, unlimited duration, with benefits) employment contract at one end and a high degree of precariousness at the other. Precarious employment might also be considered a multidimensional construct defined according to dimensions such as temporality, powerlessness, lack of benefits, and low income.

The term nonstandard work contract is defined as employment that fails to meet the standards on any dimension and typically is characterized by reduced job security, lower compensation, and impaired work conditions. Examples of nonstandard employment are part-time, seasonal, home-based, contingent, or informal work.

Contingent employment refers to work with unpredictable hours or of limited duration. Work may be unpredictable because jobs are structured to be short-term or temporary, or because the hours vary in unpredictable ways. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics has adopted this definition: short-term or temporary work contracts, unpredictably variable hours, as an ‘‘alternative employment arrangement,’’ a strategy for increasing the flexibility of work assignments. These workers are often marginalized at work; they have less training and promotion opportunities, less predictable and lower incomes, and fewer pension benefits. In countries like the United States, where health insurance is primarily derived from work, contingent employees are less likely to have health insurance. In a variety of ways, contingent work is poorly covered by government regulations over workplace safety and social safety nets. Nevertheless, some workers may seek temporary work to satisfy personal needs for flexibility, or some may choose it as a transition from unemployment to a standard job.

A sizeable proportion, although one that no doubt varies from region to region, of economic activity takes place in an informal economy. Informal economy – related to contributing family work, slavery, bonded labor, child labor, and unemployment – includes employment relations where the economic activity is not reported to government authorities. Exchange in the informal economy is either for cash or barter because cash and barter do not create records that can be tracked by the authorities. Some activity in the informal economy may be illegal even if the income or the transactions were reported. Work in the informal economy poses significant health risks because working conditions are unregulated and workers do not receive benefits.

Bonded labor and slavery is a form of forced labor that is found in different sectors of the informal economy. Millions of men, women, and children around the world are forced to lead lives as slaves. Although this exploitation is rarely called slavery, the conditions are similar. People are sold like objects, forced to work for little or no pay, and are at the mercy of their employers. According to Anti-slavery International, a slave is someone who is forced to work through mental or physical threat, owned or controlled by an ‘employer’, usually through mental or physical abuse or threatened abuse, dehumanized, treated as a commodity or bought and sold as property, and/or is physically constrained or has restrictions placed on his or her freedom of movement. Examples of slavery include bonded labor, early and forced marriage, forced labor, slavery by descent, trafficking, and the worst forms of child labor.

Child labor is ‘‘the employment of children under the age determined by law or custom’’ and is most common in the poorest countries. In many cases, child labor is accepted as a strategy of diversification of income resources to better manage household income, risk of job loss, or a failed harvest.

The relations among poverty, illiteracy, and child labor are reported as vicious circles of an indissoluble connection. These workers are reportedly exploited by many countries with high intensive labor, but they have little control over their daily work. Although the proportion of informal workers varies from region to region, a sizable proportion of informal workers may face more health risks due to their poor working conditions compared to employee groups.

Employee turnover occurs when workers leave their positions in organizations. Their reasons for leaving jobs are a measure of employee morale. The rate of employee turnover is one measure of the commitment of employees to organizational goals. Turnover is determined in part by organizational policy and management through factors such as salary, benefits, promotions, training, and work schedules, and in part by personal factors that are largely beyond employers’ control, for example, an employee’s desire to relocate. Temporal trends in the importance workers place on various reasons for leaving are useful, as they provide indirect evidence of organizational changes in the workplace.

The definition of early retirement used generally in government information to older people is retirement before state pensionable age. Some of those who retire early actively seek further employment, but many leave the labor force for good, either through ill health or by choice. Thus, the social meaning of early retirement and redundancy are not fixed but dependent on the prevailing level of unemployment and the financial implications of the different ways of leaving employment. In response to changes in public policy, early retirement in most industrialized countries rose considerably during the 1980s and most of the 1990s. However, recent policy changes are aimed at stemming this outflow of older workers from the labor market.

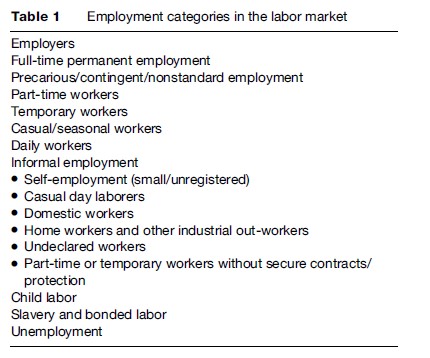

Unemployment is also an important issue in labor market. The meaning of unemployment varies in each country over time and for political purposes. Roughly speaking, unemployment is when a previously employed worker is laid off or not in gainful employment, even when they are actively seeking jobs. It often leaves out large numbers of people who would like to work but are prevented even from looking for work, such as many people with long-term illness who could work if working conditions were better, and parents who could work if child care services were adequate (Table 1).

Characteristics Of Contemporary Labor Markets: Globalization, Downsizing, Flexibility, And Job Insecurity

Globalization And Organizational Downsizing

After the era of Fordism, characterized by mass production and a stable economy, globalization and liberalization have affected the conventional labor market. Higher efficiency is achieved by a situation that includes unemployment and nonstandard work arrangements (ILO, 1997). Conversely, proponents of globalization such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) proposed that it contributes to developing countries to achieve faster economic growth resulting from foreign direct investment and technology advances (UNCTAD, 2001; Rama, 2003). Amid controversy regarding the role of globalization, several studies have found that globalization puts great emphasis on the efficiency of the world economy. The change in labor market leads to increasingly unstable employment, organizational downsizing, which is the widespread restructuring of organizations. In general, these workplace right-sizing efforts share one key objective: To reduce the costs of labor. A central aspect of this trend is downsizing the workforce through large-scale layoffs. The initial waves of downsizing in the 1970s and 1980s were mostly attributable to a process of deindustrialization and the transition to a service economy; however, since then offshore investment has increasingly involved nonmanufacturing ventures, and by the 1990s organizational downsizing involving job losses had affected workers across all sectors and occupations (Noer, 1993; Rifkin, 1995; Budros, 1997). Studies indicate that downsizing is associated with significant changes in workload and can create uncertainty around work roles and responsibilities (de Vries and Balzas, 1997; Greenglass and Burke, 2000; Moore et al., 2004). As a result, the labor market, in recent decades, has increasingly produced new forms of organization and flexible types of employment such as contract, part-time, on-call, and home-based work (Bielenski, 1999). Most flexible employment is characterized by instability, including a lack of social protection, low income, and a greater risk of layoff (Polivka, 1996; Saloniemi et al., 2004b).

Job Insecurity

Job insecurity is a key dimension of precarious work. Workers who labor under nonpermanent employment contracts and those who lack adequate protection from dismissal can be negatively affected by the persistent threat of job loss. Job insecurity is typically defined as a subjective phenomenon arising from the perceived threat to employment continuity (Ashford et al., 1989; Hartley et al., 1991; Bussing, 1999). At its core, job insecurity is an expression of the discrepancy between the level of security a person experiences and the level that he or she might prefer (Hartley et al., 1991). Because job insecurity represents a fundamental and involuntary event, it is considered a classic work stressor with health consequences consistent with demand-control models of job strain (Sverke et al., 2002). However, the global regulatory response to ameliorating the rising prevalence of job insecurity and its deleterious effects have proceeded in a somewhat piecemeal fashion. Changes in employment have outpaced the sluggish evolution of labor market legislative, social, and political mechanisms (Polaski, 2004). Part of this regulatory failure is reflected in the documented growth in perceived employment insecurity in OECD countries (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1997). There are, however, some examples of effective policy interventions that give reason for optimism.

Flexicurity As A New Paradigm In The Globalized Labor Market

A new paradigm called flexicurity (social dialogue with flexiblity and security in the job market) was also implemented in the European labor market. In Denmark, a tripartite approach involving government, business, and labor aims to combine a flexible labor market with a program of broad social security (ILO, 2006). Consequently, although employment stability in Denmark is relatively low (each year, roughly 30% of Denmark’s workers change jobs), Denmark ranked second in the job security feelings rankings of the OECD in 2000 out of a total of 17 countries (OECD, 2001). In Sweden, employers have opted to directly involve labor in the reorganization of work. This has resulted in the development of sociotechnical systems wherein job satisfaction and life-long learning are an integral aspect of the social relations of production (Gallie, 2003). Moreover, there is evidence that the presence of laws and regulations that ensure minimum standards in employment protection and in social security do not necessarily inhibit economic growth. In a survey of several countries broadly representative of three different socioeconomic models – liberal, social market, and social democratic – Jackson (2000) concluded that the strong presence of collective bargaining and labor market regulation can work to maintain a low level of earnings inequality without preventing job growth or business investment ( Jackson, 2000). Two countries in particular – the Netherlands and Denmark – provided striking examples of the ability to combine high levels of social security with strong economic performance (e.g., the average annual rate of growth in per capita GDP for the period 1990–1998 in these countries was 2.3% and 2.1%, respectively; this compares with an average rate of growth of just 1.7% in the United States) ( Jackson, 2000). Wilkinson and Lapido (2002) maintain that it is the ‘‘highly developed regulatory systems in these small, highly internationalized economies’’ that function to protect firms and workers from the shocks of global markets, and which serve to ‘‘strengthen rather than weaken their international competitiveness’’ (Wilkinson and Lapieo, 2002: 184). Hence, despite strong pressures on equality-generating institutions arising from international competition, it is not obvious that the liberal/U.S. model of turbo-charged capitalism represents best practice for promoting high rates of productivity and growth and high levels of employment performance. As the OECD (2002) explains, ‘‘more generous unemployment insurance benefits and higher union density do cause workers to report greater satisfaction with job security, perhaps because their families’ income are better protected, should they lose their jobs’’ (OECD, 2002: 268).

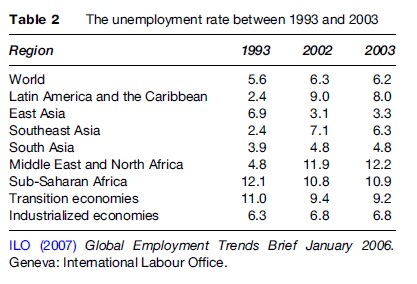

Dimensions Of Precarious Employment

Within the past few decades, labor markets around the world have been undergoing a number of drastic changes, including technological innovation, rising global competition, and an industrial shift from manufacturing to services. Although the global economy has recovered in the 21st century, it has failed to reduce the unemployment rate, and created a variety of flexible types of employment around the world. In East Asia, for example, the average annual GDP growth rate has continuously been 8.3% since 1993. However, the unemployment rate has slightly increased from 3.1% in 2002 to 3.3% in 2003 (Asian Development Bank, 2004). Furthermore, those employed are not always guaranteed decent jobs. A very high percentage of informal workers around the world are known to be employed with very low salaries and no contracts. The characteristics of the informal labor economies are mostly known for being typically unstable and lacking in legal and social protection. The shear size of unemployment is masked by a lack of information such as duration of unemployment, ethnic origin, and composition of the jobless, especially in developing countries. There was roughly 195.2 million unemployed at a global rate of 6.3% in 2006 in the world (ILO, 2007). Over the last decade, East and South Asia’s unemployment rates have been maintained at a very low 3.8% and 4.7%, respectively. The unemployment rates in the Middle East and North America (at 13.2%) were twice as much as the global average unemployment rate. In African countries south of the Sahara, the unemployment rate was recorded at about 10.9% of the economically active population. South Africa recorded the highest unemployment rate at 30% (ILO, 2004). As a consequence of rural poverty due to war, conflict, and disasters, two thirds of the population migrated from rural to urban areas. In addition, structural adjustment reforms in the 1980s have brought a rapid influx of rural population to urban areas resulting in urban slums (WHO, 2007). Constant conflicts and rapid urbanization in Africa led to increase in unemployment, especially in youth unemployment (nearly 80% of total unemployed). An ILO report from 2007 outlined that the unemployment rate for adolescents was almost three times greater than those for adults worldwide. According to a report from the Economic and Social Research Council, the unemployment rate of eight OECD countries has steadily increased from the 1970s to the 1990s, ranging from 4 to 12%. The unemployment rate among women is considerably higher than among men, with the largest gaps in Spain at 12%, 9% in Greece, 6% in Italy, 4% in both France and the Czech Republic, and no change in the UK in 1999. Overall, the unemployment rate is closely linked to lower education groups. People with lower education were three times more likely to be unemployed than those with higher education. An estimated 500 million unemployed people survives at the extreme poverty level, making less than US $1 a day (ILO, 2007).

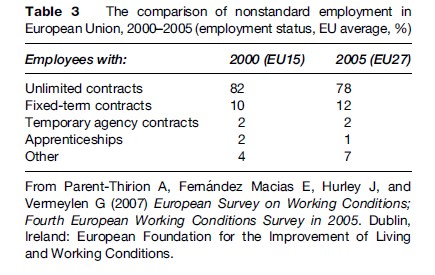

With this background, nonstandard employment in Europe has been an important job creation strategy to reducing the unemployment since the 1970s. Nonstandard employment arrangements regarding fixed-term, temporary, and part-time work have steadily increased since 1990 (UNECE, 2003). Marmot (1999) reported that the proportion of European workers in nonstandard employment increased from 5% in 1970 to 30% in 1990. The trend toward nonstandard employment is expected to continue worldwide (Ostry and Spiegel, 2004). According to the Fourth European Working Conditions Survey (Parent-Thirion et al., 2007), the percentage of part-timers among workers has steadily increased in the EU27 from 17% in 2000 to 20% in 2005, while the percentage of nonpermanent contractors has slightly decreased from 13% in 2000 to 12% in 2005. Meanwhile, the proportion of the standard contract decreased from 82% in 2000 to 78% in 2005 on average in the EU27. Part-time work is more common in the services sector (30%), the health (28%) and, retail sectors (27%), education (24%), and the wholesale and retail trade (23%). Surveys also show that nonstandard workers such as part-time (25%) and nonpermanent workers (23%) are less likely to have an opportunity of training and promotion than full-timers (30%) (Parent-Thirion et al., 2007). Although female labor participation has expanded significantly, more women are marginalized into jobs with low salaries and easily laid-off due to gender discrimination and sexual segregation (OECD, 2002). As a result, the percentage of female nonstandard workers has continued rising from 40% in 1970 to roughly 55% in 2000. OECD (2002) reported that an average of 26% of women and 7% of men worked as part-timers. Employed women are working more as parttimers: 57% of employed women in the Netherlands, 40% in Australia, Norway, Switzerland, and the United

Kingdom, and approximately 10% in Eastern European countries, Greece, and Korea. However, women with a tertiary qualification have more opportunities to get well-paid jobs compared to less educated women in most of the OECD countries, except for Japan and Korea.

Most flexible employment is characterized by instability, including a lack of social protection, low income, and a greater risk of layoff (Polivka, 1996; Saloniemi, 2004). In Europe, characteristics of workers in nonstandard employment tend to include female gender, young age, and relatively little education (Polivka, 1996; Saloniemi, 2004a). Although women are increasingly becoming wage earners (from 36% in 1960 to 48% in 2000), they are overrepresented in nonstandard employment, and are especially concentrated in skilled manual occupations with unfavorable working conditions (Matthews et al., 1998; Bartley, 1999; O’Campo et al., 2004). Women tend to choose nonstandard jobs because of their role as family caregiver. More than half of fixed-term contract workers in the European Union (EU) are young (under 30). They are mostly students who have chosen to work part-time as they study (Ahn and Mira, 2001; Chaykowski, 2005). Some young workers with a low level of education tend to choose unskilled nonstandard work. Overall, the occupational distribution of nonstandard workers varies widely from highly skilled jobs to unskilled labor such as janitorial or cleaning work (Polivka, 1996).

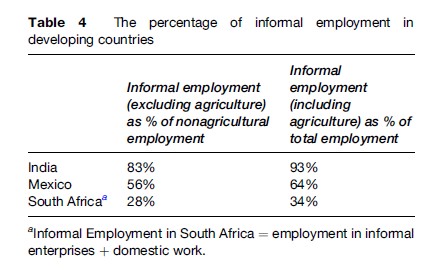

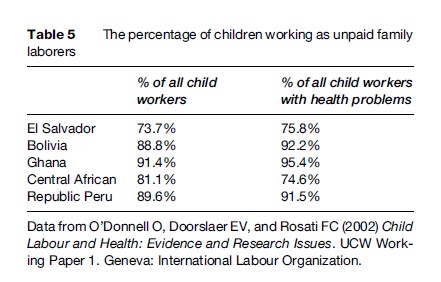

The informal economy comprises two components: Informal enterprises and informal jobs (ILO, 2005). Informal enterprises generally include three parts: Microenterprises with an employer and some employees, family businesses with unpaid family workers, and own-account operations. Informal jobs usually mean irregular, unstable, unprotected jobs that include domestic work with no regular contract, casual day labor, industrial outwork for formal and informal firms, unregistered or undeclared work, and temporary and part-time work. Due to insufficient worldwide data, the size of the informal economy was estimated by indirect methods. According to an ILO survey in 2005, over half of the labor force around the world was known as informal jobholders. One-third of total nonagricultural employment is categorized as self-employment. In developed countries, informal workers consist of mostly the self-employed, part-timers, and temporary workers, which is approximately 30% in Europe and 25% in the United States among total employment in the late 1990s. Self-employment is estimated at less than 15% of total nonagricultural employment. In developing countries, the informal economy is one of the largest sources of employment. It comprises one-half to three-fourths of nonagriculture employment: 48% in North Africa, 51% in Latin America, 65% in Asia, and 72% in sub-Saharan Africa (ILO, 2002). Most developing countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and India reported that over 70% of total employment is related to non-agricultural informal occupations (ILO, 2005). Self-employment arrangements comprise as much as 50% of nonagricultural employment in developing countries. Similarly to self-employment, 30–40% of informal employment accounts for informal wage employment, such as casual day labor and domestic work without a fixed contract. In the context of accelerated industrialization, informal employment will continuely expand more in developing countries (Quinlan et al., 2001). Recent studies suggest that the informal economy is severely gender segregated. Except in North Africa, working women concentrate more highly in informal employment than working men. Nearly 60% or more of women workers are engaged in nonagricultural informal work in the developing countries. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, 84% of working women are informally employed compared to 63% of working men. Contrary to Africa, the proportion of informal workers in Asia appeared to be almost equivalent in both genders (ILO, 2002). Women are more likely to work in the low strata of the informal economy than men (after Chen et al., 2004). In Peru, 36% of employed women are more likely to work at unpaid family work, compared to around 12% of men. On the contrary, a higher percentage of men (35%) than women (14%) is involved in wage work (after Chen et al., 2004). A survey in Ghana (Ghana Statistical Service, 2000) showed a similar result in line with previous findings (11% of men and 35% of women are unpaid family workers). Characteristics of informal work are generally job insecurity, low salaries, and lack of fringe benefits. Even when they work for 40 h per week, they were paid below the minimum wage or often not paid at all. Workers within the informal job market tend to have low socioeconomic status or less education. In OECD countries, temporary workers and part-timers receive an hourly salary rate that is 50–90% of regular based workers. As a general rule, a few of them receive social fringe benefits such as pensions, sick leave, and health insurance. For instance, in the United States, only less than 20% of informal workers have health insurance and a pension. Also, self-employed workers are usually ineligible for unemployment insurance. In developing countries, informal workers work mostly in semi-skilled or unskilled jobs (Daza, 2005). The majority of those who have informal jobs have not received any formal training. Wage earnings vary greatly, depending on informal sectors or regions. The specifically self-employed earnings ranged from 1.5 to 5.8 times the minimum wage (Blunch et al., 2001). In developing countries, a large share of the informal economy involves outdoor activities such as street vending, advertising. Workers in the informal economy tend to move to another job and face seasonal fluctuations in work or have more than one job. Whether they work at home or not, these workers are at an increased risk of injuries and occupation-related diseases. Turnover in the informal sector is twice what it is in the formal sector. According to UNICEF research, much of informal employment suffers from a minimum level of income, which does not cover minimal expenses, especially female informal workers. Over 60% of women in developing countries engaged in the informal economy with lower-status jobs earn less than men (UNICEF, 2006). Women with small children suffer more from economic hardship and lack of benefits such as maternity leave or retirement benefits provided for regular full-time workers (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5).

The number of child laborers aged 5–17 was estimated at approximately 218 million for the year 2006, excluding child domestic labor (UNICEF, 2006). The population of child laborers worldwide is approximately 127 million in the Asian and Pacific region, 48 million in sub-Saharan Africa, 17.4 million in Latin America, and 2.5 million in the Middle East and North Africa (UNICEF, 2006). In developing countries, the proportion of child labor varied enormously, ranging from 4% in Timor-Leste, Asia, to 67% in Niger, Africa, and 63% in Togo. In Burkina Faso, the proportion of child laborers reportedly is 57%, similar to other African countries such as Sierra Leone, Ghana, and Chad. Boys were more likely to be in the labor market than girls in most countries (UNICEF, 2006). According to the ILO report (ILO, 2006a), over 70% of child laborers work in agriculture. UNICEF research revealed that roughly 128 million child labors work in agriculture worldwide. The child labor in the agriculture sector far outnumbered (more than ten times) the numbers in factory work such as carpet-weaving, or garment manufacturing (Human Rights Watch, 2006). Child laborers are often exposed to dangerous working environments such as long working hours as well as physical and psychological harm. Roughly 50% of child laborers are reportedly engaged in a hazardous working environment containing dust, chemicals and pesticides, heat and harsh weather, intensive labor, and dangerous tools (hoes, tractors, etc.). About 1.2 million girl workers are involved in sexual abuse and violence because of debt bondage and slavery (UNICEF, 2007). Many school-aged children are deprived of the fundamental right to education. Many working children are subjected to forced or compulsory recruitment, a form of slavery. Worldwide, more than one million children are involved in human trafficking annually for slave labor, prostitution, drug selling, and sometimes war combat. The worst forms of child labor are documented by over 20 countries such as Angola, Burma, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda. Approximately 20–30 million children are recruited for use in armed conflict. Slavery and bonded labor are widespread in Asia and Africa, although it is considered a crime. Sometimes the unemployed are in such desperate or extreme poverty that they are vulnerable to undesired work. They are likely to fall into servitude or are victimized by fraudulent or deceptive means. Forced to work in dangerous conditions, these children are being exploited, tortured, raped, and sometimes murdered. Surveillance systems monitor them so they cannot escape. Their life is totally constrained to the workplace (Free The Slaves, 2004). To cite an example, there is the case of a 7-year-old boy working on a cocoa farm. Among almost 700 000 cocoa farmers working on cocoa farms in Cote d’Ivoire are 15 000 slave children. Aly Diabate from Mali was 11 years old when he was lured in Mali by a slave trader to go work on an Ivorian farm. Life on the cocoa farm of Le Gros (or Big Man) was nothing like Aly had imagined. He and the other workers had to work from 6 am to about 6:30 pm in the cocoa fields. Since Aly was only about 4 ft tall, the bags of cocoa beans were taller than he was. Aly was beaten the most because the farmer accused him of never working hard enough. The little boy still has the scars left from the bike chains and cocoa tree branches that Le Gros used. He and 18 other slave workers had to stay in their one room that measured 24 20 ft. There was only a single small hole just big enough to let in some air. Aly and the others had to urinate in a can, because once they went into the room, they were not allowed to leave, with the room locked (Chatterjee et al., 2001).

Employment Status And Health

Unemployment And Health

Research concerning the negative health impact of unemployment is well established. In the competitive labor market worldwide, growing unemployment and its related health issues have received much research attention. A large body of evidence has accumulated relating unemployment to higher risk of mortality rates caused by heart disease and suicide ( Jin et al., 1995). It also tended to be related to poor mental health such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia. According to stress theory, concern about the future of their job – unemployment or job insecurity – may be the indirect consequence of job stress caused by physiological changes, changed health behavior, as well as deteriorated health. Studies showed that lifestyle factors such as heavy drink, smoking, and psychoactive drug use are more common in the jobless, seen especially in young men as a result of more leisure time or as a coping strategy ( Jin et al., 1995; Khlat et al., 2004). The social support model explains that unemployment leads to increased social exclusion, economic exclusion, and social isolation, which in turn can demolish the social support system. Long-term unemployment of youth could threaten their overall integration into society (Kieselbach, 2003). Studies investigating the use of healthcare services for the unemployed show contradictory results depending on the health-care system available. In countries with a comprehensive health-care system like England and Canada, the unemployed used the health-care system significantly more than the general population. On the contrary, the access to health care on the part of the unemployed was limited by expensive costs of private medical treatment (Harris et al., 1998).

The relationship between unemployment and health can be explained by two mechanisms: The health of people who are unemployed can deteriorate or those with poor health can easily be excluded from the labor market. Most unemployed people suffer from economic hardship and this uncertainty in their future could possibly be associated with psychological and physiological strain. On the contrary, those who have poor health may be hampered from entering the labor market or have a high risk of unemployment (reverse selection hypothesis). An important longitudinal study from Finland found a positive association between unemployment and mental disorder and digestive disease. However, it is also true that unemployment is related to protection from musculoskeletal diseases (Heponiemi et al., 2007). In addition, the incidence of motor vehicle fatalities tends to be lower.

Precarious Employment And Health

In terms of the growing number of nonstandard workers, there are two contradictory arguments: The first views increasing nonstandard work as a consequence of the market principle, namely supply and demand, while the other argues that nonstandard work arrangements have brought a great burden of job insecurity to the labor market. Although nonstandard contracts are one of the solutions to escape inflexibility in the market, there is also concern about the quality of jobs and lack of opportunities for career improvement related to nonstandard jobs (Booth et al., 2002). Also, much evidence has been accumulated on the unfavorable conditions faced by these nonstandard workers such as lower salaries, lack of opportunities for promotion, an insufficient social safety net, and lower level of job control, compared to standard workers. Meanwhile, there is still controversy on whether nonstandard jobs are a kind of dead-end job in the peripheral segment of the labor market. A recent study from Finland suggests that nonstandard work could be a bridge for moving to a standard position (Saloniemi et al., 2004a). However, considering the realities of combined nonstandard work conditions without a welfare system, nonstandard jobs could still be a poverty trap worldwide. In the past few decades, empirical studies have found evidence that nonstandard work is associated with detrimental effects on physical health, mental health, self-rated health, and mortality (Virtanen et al., 2005). A recent study in Finland found an association between nonstandard work and mortality regarding drinking and smoking-related cancer (Kivimaki et al., 2000). The disadvantageous characteristics of precarious work are generally considered to be associated with psychosocial problems, including anxiety, depression, suicide, and substance abuse (Friedland and Price, 2003; Ludermir and Lewis, 2003). A cross-sectional survey suggested that precarious workers have an adverse impact on common mental disorders, and this result remained after controlling for socioeconomic position (age, sex, marital status, education, and income) (Ludermir and Lewis, 2003). A comparative study of 15

EU countries supported the previous finding that fixed-term and temporary workers are related with a higher risk of fatigue than standard counterparts (Benavides et al., 2000). Workplace risk factors for mental health involve exposure to hazardous material, lack of autonomy, high job demands, and an effort-reward imbalance (Wilhelm et al., 2004). According to Siegrist’s hypothesis, those workers carry great demand, lower control, poor psychosocial working conditions, and lower wages (Saloniemi et al., 2004b). In this view point, precarious work is likely to have a greater impact on physical health than a standard job. Chronic conditions, especially musculoskeletal disease, have been studied as an important barrier to productivity (Burton et al., 2001; Lerner et al., 2005). Also, socioeconomic health inequality has been widely studied using self-rated health outcome measures. Selfrated health describes chronic disease, long-term disability (Goldstein et al., 1984). The finding of the employment inequality in self-rated health may reflect the accumulated disadvantage during their occupational history (Anitua and Esnaola, 2000). The positive association with musculoskeletal disorders with nonstandard employment may represent the cumulative risk and latent periods of physical factors such as heavy and frequent lifting or carrying and extreme forward bending (Devereux et al., 2002). Findings from South Korea are similar to the previous study, showing that nonstandard employees were mostly assigned to extremely repetitive and heavy work, causing frequent absences for illness, lower productivity, and higher mental disorder (Kim et al., 2006). Missed work for illness reasons is used as an essential indicator of morbidity in occupational medicine in all countries. A Dutch study (Notenbomer et al., 2006) found that absence for sickness was related to physical demands, job autonomy, and education level. These findings laid the ground for the association between nonstandard work and absenteeism. However, many empirical studies revealed that precarious job holders were negatively associated with job satisfaction and absenteeism (Benavides et al., 2000; Virtanen et al., 2005). When workers move up from precarious to permanent jobs, job satisfaction improved and increased absence due to sickness, compared to nonstandard jobholders. A possible explanation is that the difference may originate from thresholds of sickness or from the fear of getting laid off in case of absenteeism. As outlined by Mackenbach et al. (1996), people with higher socioeconomic position were likely to perceive their health conditions as poorer than those with lower socioeconomic position, presumably due to higher expectations from the good quality of health information and education (Goldstein et al., 1984; Dunlop et al., 2000). Contrary to previous findings, some research found no relation between nonstandard work and poor health, including depression and psychological distress (Virtanen et al., 2003b). In addition, a few studies suggested that nonstandard workers were in better health than standard workers (Rodriguez, 2002). This discrepancy in findings could be explained by varying levels of legal and social protection for workers in societies.

Informal Employment And Health

The empirical research on the relations between informal economies and occupational health outcomes have been much hampered because of the lack of available health-related database and official statistics in informal economies. Some features of informal employment, including scattered spatial distribution of small-scale businesses and domestic work or street vendors make it more difficult to research. Another technical issue is that the large heterogeneity of informal employment could be a deterrent to reaching the consensus of an acceptable standard definition, although it is roughly explained in terms of their general employment characteristics. An accurate definition of informal employment is required before the current health condition of affected informal workers can be identified.

Recently, the empirical evidence available reveals that workers in the informal sector were related with much higher risks of unfavorable health conditions compared to those in the formal sector. A Brazilian study shows that higher annual nonfatal injuries are more common among women with a medium level of education and unskilled jobs compared to regular, full-time jobholders (Santana and Loomis, 2004). In terms of government laws regarding informal jobs, there are no clear labor regulations to protect informal workers from work-related hazardous materials. Although occupational injuries are one of the most important preventable health problems, the characteristics of the informal economy without proper social protection cause workers more exposure to occupational hazardous conditions compared to regular workers who have a supervisor on the work site. In addition, informal jobholders seem to withhold reporting injuries or ignore the condition from lack of training and a fear of layoff (Quinlan et al., 2001). A recent result from a longitudinal study showed that an adult representative sample of the U.S. population moderately approves the expectation that underemployed workers who hold part-time jobs, have a low income and little opportunity for skill training are related to lower levels of psychological well-being (Friedland and Price, 2003). In many developing countries, especially in Africa, informal workers report excessive exposure to hazardous materials such as dust, fumes, chemicals, or sunlight without personal protective equipment at the work site. A Zimbabwean study (Loewenson, 1998) found a correlation between informal workers and excessive risks of musculoskeletal and respiratory diseases. The annual occupational mortality rate and the rate of workers injured in the workplace were 12.5 persons per 100 000 workers and 131 persons per 1000 workers, respectively. One-fifth of the injuries resulted in permanent disability, but workers’ compensation was not provided. The World Health Organization (1997) estimated that approximately one million occupation diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa threatened informal workers’ health. Zimbabwean official statistics of occupational health might underestimate informal workers’ health problems. A recent study from Tanzania (Rongo, 2004) supported the previous findings that informal workers in small-scale industries were exposed to various hazardous conditions resulting in a high level of occupational health problems. In Botswana, data related with its informal economy are not available. Roughly 5 million of the 5.6 million businesses are engaged in small-business and micro-business activities. Although this sector has contributed to job creation and provided regular income, this type of informal work is extremely precarious and unsafe. Common types of informal economies are involved in brick making, carpentry, metal work, and auto repairs. Most workers are exposed to high risks of fire, welding sparks, fumes, chemicals, and harsh weather, and work with inadequate equipment and lack of sanitary facilities. These potentially hazardous factors play a crucial role in contributing to high risks of physical injuries and mental disorders for informal workers (Karanja et al., 2003).

Child Labor And Health

Several epidemiological studies have found child labor to be associated with increased musculoskeletal disorders, physical impairment, and psychological distress (Fassa, 2003; Guarcello et al., 2004), but the effect of child labor on various health problems has not been fully explored because of a lack of qualified data. The negative impacts on health vary widely, from occupational-related injuries to increased vulnerability to biological and toxic agents or ergonomic risks from use of inadequate tools and equipment. Child laborers are overrepresented in dangerous informal employment and are especially concentrated in agriculture with unfavorable working conditions (69%) (ILO, 2006a). Children in agriculture are subjected to much worse working conditions than other informal workers. These children have little control over their employment, are exposed to pesticides, heat and harsh weather, and hazardous equipment (Fassa, 2003; UNICEF, 2007). Increasing evidence has shown that the hazardous conditions of child laborers are the most common cause of musculoskeletal disorders, cancer, hearing loss, asthma, and pesticide poisoning (Fassa, 2003; UNICEF, 2007). For instance, children working at rug looms are subject to disability from eye damage, lung disease, stunted growth, and are susceptible to arthritis in the future. In India, children making silk thread are in danger of injuries from burns and blisters as they dip their hands into boiling water (Human Rights Watch, 2006). Children may be more vulnerable than adults working in similar conditions due to a child’s physical and mental immaturity (O’Donnell et al., 2002).

Child laborers working in urban areas are often exposed to intensive labor, drugs, physical and sexual abuse, and undesired pregnancy (O’Donnell et al., 2002; Vilma et al., 2005; UNICEF, 2006). They may easily develop physical or mental health problems arising from the unfavorable working conditions such as street selling, rag picking, construction, and prostitution. Kassouf et al. (2001) suggested that the child laborers who started work before the age of 10 were strongly associated with poorer self-rated health than those who have not worked as a child. These adverse working conditions for child laborers may be linked to increased health problems during the course of their lives. Contrary to these results, Huk-Wieliczuk (2005) suggested that child laborers with heavy workloads have no association with poor self-rated health. Further studies show a positive relationship between child laborers and their health since they are helping their family or gaining work experience and skills. A few studies have supported the hypothesis that child labor may reduce the high risk of health problems (Appleton and Song, 1999; Smith, 1999). These inconsistent findings from self-rated health on child laborers can be explained by the time-lag effect on child laborers. For children under the extreme poverty level, the argument for positive heath effects of child labor is still plausible. However, this connection cannot be definitively defined without further research. Empirical studies show that child labor is related with illiteracy, poverty, and poorly trained, low-skilled workers. It is a well-established fact that a positive relationship exits between lower education and poor health, such as mental disorders (Patel and Kleinman, 2003), malnutrition, stunted growth (Ram, 2006), and a lower life expectancy (Fassa, 2003). To understand the intricate association between child labor and health in the informal labor market, the research should be extended to monitor the trend in the effect by different social contexts over time.

Slavery And Bonded Labor And Health

It is widely believed that children exploited in slavery and bonded or forced labor systems are exposed to biological and chemical hazards, leaving them with physical, emotional, and psychosocial trauma. Supporting documents to further disseminate slavery issues focusing on their health are limited. Forced child labor may be illustrated as hidden and inhuman crimes, and it even includes involuntary sex trafficking. Child forced into labor suffer from abusive conditions, including physical and psychological violence, which are designed to keep them obedient. A U.S. study suggests a relationship between forced labor and traumatic conditions regarding physical and psychological assaults, risk behavior, inadequate or nonexistent health care, and cultural barriers (Free The Slaves, 2004). Hyde and Bales (2006) suggested that child laborers exposed to the dehumanizing violence of slave labor experience increasingly detrimental results to their health and their moral background is greatly influenced. Moreover, the effect reportedly persists and deteriorates their health, even after their period of slavery is finished. This is supported by evidence from interviews and observations of rehabilitating children set free from slavery: Their traumatic experience (exploitation, torture, or abuse) was likely to increase physical problems (stunted growth, malnutrition, burn, bruises, parasites, and HIV) and psychosocial illness (fear, anxiety, aggressiveness, dissociation, and obsessive-compulsive disorder).

Every child the world over should be protected to enhance their basic necessities such as safety, food, sleep, hygiene, and medical care. To tackle the problem of slavery and the worst cases of the illegal economy exploiting children, it is necessary to enforce an effective monitoring strategy at both the country and international level.

Downsizing And Health

Research on the occupational health consequences of organizational downsizing has focused on two major risk factors: (1) Job insecurity and (2) work intensification and disorganization. Both types of study typically collect data from workers over time, from the announcement of impending layoffs, to the post termination phase. The first type of study investigates downsizing as the major objective factor that precipitates job insecurity as an occupational stressor. Findings from these studies are fairly consistent in demonstrating a link between workplace downsizings and compromised psychological and physical health outcomes. In particular, employees facing layoff are at greater risk of experiencing mental or emotional health problems such as distress and anxiety, negative physiological changes including increases in blood pressure and cholesterol, and decreases in global self-rated health (Mattiason et al., 1990; Seigrist, 1991; Amick et al., 1998; Ferrie et al., 1995, 1998a, 1998b; Isaksson et al., 1999; Probst, 2000).

Other studies have focused on the effect of downsizing on how work is organized and distributed within the organization. Studies indicate that downsizing is associated with significant changes in workload and can create uncertainty around work roles and responsibilities (de Vries and Balzas, 1997; Greenglass and Burke, 2000; Moore et al., 2004). Employees subject to work intensification and disorganization due to downsizing have been found to be at increased risk of injury or illness, psychological morbidity (particularly depression and burnout), and declines in global self-rated health (Farr, 1996; Fridkin et al., 1996; de Vries and Balzas, 1997; Brown et al., 2003). In addition, increases in work-related pressures have been shown to interfere with work-life balance and to impair social and familial relationships (Burke and Greenglass, 1999; Kivimaki et al., 2000; Westman et al., 2001). At the firm level, downsizing is reportedly associated with increases in the rate and/or duration of sickness absence (Beale and Nethercott, 1988; Kivimaki, 1997; Kivimaki et al., 2000; Vahtera et al., 2004), and the frequency of occupational violence (Snyder, 1994; McCarthy, 1996; Sheehan et al., 1998). At least one study has found that recent downsizing is related to an increase in the duration of workers’ compensation claims (Park and Butler, 2001).

Another key aspect of workplace downsizing is unemployment caused by job loss, a factor that is strongly related to poor health outcomes (Avison, 2001; Pohjola, 2001; Turner, 1995). Studies of displaced workers indicate that these individuals often have insecure prospects for reemployment and can experience prolonged periods of unemployment or underemployment (de Vries and Balzas, 1997; Ferrie et al., 2001a; Ostry et al., 2001). Moreover, postdisplacement jobs are often inferior in quality relative to predisplacement employment with respect to skill use, earnings and benefits, and opportunities for career development (Feldman, 1995; de Vries and Balzas, 1997; Brand, 2005). Workers who experience late-life job displacement may be particularly vulnerable to deteriorating employment prospects. Studies of workers undergoing involuntary job loss indicate that, relative to their younger counterparts, older people tend to experience more prolonged jobless spells and more substantial losses in earnings, job security, and occupational status (Gallo, 1999). The post-displacement pattern involving downward mobility and financial insecurity is particularly pronounced in older women (Gilberto, 1997; Quadagno et al., 2001). Within some sectors of the economy, organizational downsizing has given rise to another trend described as disguised employment. This refers to the circumstance where an employer treats a worker as an independent contractor or self-employed person to avoid the responsibilities and costs associated with being an employer (Law Commission of Canada, 2004). During workplace restructuring, workers who were previously employed under traditional ongoing employment contracts may be reassigned to the status of independent contractor, even though they perform the same duties and functions that they did when they were employed by the firm (Law Commission of Canada, 2004). This shift in employment status is frequently associated with reduced earnings and job security, a lack of access to important statutory benefits and protections (e.g., employment standards protections, workers’ compensation, the right to collective bargaining), and a lack of access to employer-sponsored benefits such as health and disability insurance, and private pensions (Hipple and Stewart, 1996; Law Commission of Canada, 2004). Moreover, this type of change in employment status within the same organization may be a unique source of occupational stress (Gallagher, 2005).

Job Insecurity And Health

Studies of the effects of exposure to job insecurity present relatively consistent evidence for the adverse impact on health. Job insecurity is reportedly associated with mental and emotional health problems such as anxiety and depression, negative physiological changes including increases in levels of blood pressure and cholesterol, and increases in general psychosomatic sequelae such as sleeplessness, headaches, and declines in self-rated health (Mattiason et al., 1990; Roskies and Louis-Guerin, 1990; van Vuuren et al., 1991; Heany et al., 1994; Ferrie et al., 1995, 1998b). Other studies have documented a link between job insecurity and impaired social and family relations (Wilson et al., 1993; Larson et al., 1994; Fox and Chancey, 1998). At the level of the organization, job insecurity has been linked to heightened rates of sickness absence, injury rates, and occupational violence (Beale and Nethercott, 1988; Snyder, 1994; Vahtera et al., 1998; Bourdouxhe and Toulouse, 2001; Probst and Brubaker, 2001; Kivimaki et al., 2001; Probst, 2004; Cole et al., 2005).

There is also evidence that the health effects of job insecurity are cumulative. Longitudinal investigations have shown that extended periods of job insecurity can produce an increase in the number of physical and psychological symptoms compared to situations where job insecurity is observed at a single point in time. These studies have found that chronic job insecurity has a dose–response relationship with self-reported health and measures of physical symptoms, and it greatly increases the risk of minor psychiatric morbidity (Dekker and Schaufeli, 1995; Heany et al., 1994; Domenighetti et al., 1999; Marmot et al., 2001; Ferrie et al., 2002). There is also evidence of a strong association between chronic job insecurity and increases in body mass index (BMI) (Ferrie et al., 2001b). Moreover, job insecurity appears to have residual effects; that is, the adverse effects on health are not completely reversed by removal of the threat and increase with chronic exposure to the stressor (Ferrie et al., 2002).

A handful of studies have considered the social distribution of job insecurity and its health consequences. This research indicates that both exposure and vulnerability to job insecurity as an occupational stressor varies according to sociodemographic characteristics denoting social position, e.g., social and economic class, gender, race, and age. Lynch et al. (1997) have reported gradients of exposure to job insecurity according to socioeconomic position. Other research indicates that employees in blue-collar manual jobs experience greater strain due to perceived threats of unemployment compared to employees in nonmanual jobs (De Witte, 1999; Lynch et al., 1997). Gender differences in the health effects of job insecurity have also been reported. In general, these studies indicate that the deleterious effects of job insecurity are more pronounced in men. Ferrie et al. (1998) found that men who experienced job insecurity exhibited significantly greater increases in self-reported physical and psychological morbidity compared to women, though women demonstrated small adverse changes in health behaviors not observed in men. According to De Witte (1999), job insecurity is associated with significant increases in distress in men but not in women. A study of Taiwanese employees found that the negative health impact of job insecurity is greater in men, though among women, the adverse effects were more pronounced in individuals who held managerial or professional jobs compared to those in lower employment grades. The authors suggest that women in senior positions may be more invested in their work roles than women in lower occupational positions (Axelrod and Gavin, 1980). Racial differences in perceived job insecurity have been reported by Wilson, who describes the greater perceived levels of insecurity perceived by African-Americans as the result of objective differences in levels of vulnerability to dismissal compared to Whites. Some evidence for the incremental effects of job insecurity arising from older age has been reported by Vaherta et al. (1998). In their study of downsized employees, the authors found that individuals aged 44 or older were at significantly greater risk for medically certified sick leave relative to their younger counterparts.

The limited research on the social patterning of job insecurity and the links to health indicate that further work in this area is needed. Ferrie et al. (2001b) have recently called on researchers to develop studies that systematically address the ‘‘distribution of job insecurity by social class, age, and gender, and the contribution of acute and chronic job insecurity to widening socioeconomic inequalities and gender differences in morbidity and mortality’’ (Ferrie et al., 2001b: 75). Although most researchers adopt a global view of job insecurity as an overall concern about the existence of the job in the future, some have recommended a multidimensional definition of the construct. For instance, Campbell (1997) has isolated four possible sources of work-based insecurity including fears regarding job loss, loss of income, unpredictable work schedules, and the lack of employability. De Witte (1997) has reported several aspects of insecurity arising from the loss of valued benefits from labor-market engagement such as contact with social networks, help with structuring time, and the opportunity to develop skill sets. Scott (2005) has argued that standard definitions of job insecurity fail to capture several emerging aspects of insecurity within contemporary employment relations. In particular, the exclusive focus on the perceived threat of job loss obscures the more general and fundamental pattern of work-based insecurity arising from multiple threats to the quality of employment. This refers not only to psychosocial aspects of the work environment (e.g., the subjective threat of becoming unemployed), but also to the impact of structural workplace determinants such as the lack of unionization, low wages, or the absence of benefits (Cheng et al., 2005). A recent empirical investigation of the impact of exposure to multiple emergent aspects of insecurity within nominally secure employment arrangements (i.e., full-time permanent jobs) found that employees’ health is adversely affected by earnings and benefits inadequacy, the absence of career advancement opportunities, and the lack of control over work processes arising from work intensification and substantial unpaid overtime hours (Wilson, 2002).

Gender, Precarious Work, And Health

Recently, much empirical evidence has suggested that precarious employment is associated with detrimental effects on physical and psychological health, self-rated health, and mortality (Jin et al., 1995; Campbell, 1997; Janlert, 1997; Vahtera et al., 1998; Benach et al., 2002; Huk-Wieliczuk, 2005; Scott, 2005). However, the relationship between women’s health and their working status has not been fully explored. Due to rapidly changing social and economic circumstances, the female participation rate in the labor market is at a historically high level, 68% worldwide, and is expected to continue to increase in the future (O’Donnell et al., 2002; Santana and Loomis, 2004). Most female workers are estimated to occupy the low-income strata of employment status worldwide; more than 60% of working women are in part-time work in all OECD countries and in informal employment in the developing world (Santana et al., 1997). Female workers, in particular, tend to have secondary labor market or marginal jobs with more adverse job characteristics than men (Schwefel, 1986; ILO, 2004). It is widely assumed that women face structural inequality, job segregation, and discrimination in most workplaces; they have lower hourly salaries, spend more time doing housework duties than formal workers, have less opportunity to train for job skills, and are easily fired (ILO, 2002, 2004). Clear evidence shows that female informal work is linked with low socioeconomic status (less educated or low-income families) (Matthews et al., 1998).

Many studies have examined gender-based patterns of ill health according to employment status. Brazilian studies show that positive associations between female informal workers and a number of psychological symptoms exist (ILO, 2002; O’Campo et al., 2004). Another study reveals that, compared to full-time workers, informal workers such as part-timers, temporary workers, and home-based workers share several psychosocial symptoms with women, but not with men (Standing, 1997; Devereux et al., 2002; ILO, 2002; Ludermir and Lewis, 2005). A contrasting result was found by De Witte et al. (1999); job insecurity is related to psychological well-being only in male workers. Women with mental health problems may have been prevented from having a formal job; otherwise working women may often quit their decent job at the onset of mental disorders. Although reasons for gender differences in mental disorders have not been fully studied, further research should consider the social role and cultural backgrounds within the labor market. For instance, female workers may have a lot of stress from multiple roles, such as taking care of family as well as performing household chores. These women are also exposed to discriminatory working environments. Thus, women working in precarious employment may easily acquire psychological symptoms arising from restricted opportunities for training, less job control, and a high risk of dismissal, as well as the possibility of sexual abuse. Moreover, the harsh and intensive labor conditions of informal jobs have been shown to manifest themselves in musculoskeletal and physical disorders (Santana et al., 1997; Ludermir and Lewis, 2005). The research on the relationship between unemployed women and mental health has been even more hampered since most women performing unpaid family work can be designated as housewives rather than as unemployed. Evidence from empirical studies suggests that female workers outside the home have an advantage over unpaid family workers, since they have a protective effect for their psychological symptoms from social support (De Witte, 1999; Santana, Loomis, Newman et al., 1997). Contrary to the results, female paid employees with the burden of family care may diminish the benefits from employment (De Witte, 1999; Santana and Loomis, 2004; Ferrie et al., 2005). Considering the vast majority of female informal workers in both developed and developing countries, more research should be done on the detrimental health effects and the mechanism related to adverse working environments of women.

Interventions

In an effort to combat the negative impact of downsizing on remaining employees, employers have implemented different types of organizational interventions. One major type of intervention is aimed at modifying the negative consequences of the insecurity arising from workplace change through improving communication within the organization. Buono and Bowditch (1989) first noted that during times of organizational transition, rumors will often play a major role in determining employee perceptions, which can exacerbate employee anxiety. Consequently, interventions that are designed to enhance the communication of factual information to employees during workplace restructuring can be critical to attenuating the negative effects of job insecurity on employees’ physical and psychological outcomes (Santana and Loomis, 2004; Ferrie et al., 2005; ILO, 2007). Other forms of organizational intervention that have proven effective against the adverse effects of job insecurity involve increasing employee participative decision making (Buono and Bowditch, 1989; Santana and Loomis, 2004). These initiatives allow employees to regain a sense of control over aspects of the job that may have otherwise been lost during workplace restructuring. Studies of participatory interventions indicate that employees who are provided with a greater number of learning opportunities and higher levels of decision authority experience fewer negative consequences as a function of job insecurity and other sources of occupational stress (Appelbaum and Donia, 2001; Schweiger and DeNisi, 1991).

Generally, trends in workplace restructuring that have resulted in an increasing overlap between paid employees and the self-employed have prompted organizations such as the OECD and the ILO to call on countries to scrutinize the growth of nominal or disguised self-employment and devise policies to extend social protections and benefits to this segment of the self-employed (Probst, 2003). However, the extent to which countries have implemented labor market regulatory mechanisms involving such protections varies considerably (Liden and Tewksbury, 1995). For example, some European countries provide not only full-time but also precarious workers with equal legal rights such as periods of notice or redundancy pay and martial leave, which are likely to improve the health of precarious workers in those countries.

In conclusion, egalitarian social policy programs regardless of employment status are prerequisite steps to improving the health of precarious workers. For instance, as a successful Dutch case suggested, it is recommended to provide social investment in early childhood, equal opportunities for education and training regardless of employment status, a sound partnership between employers and employees, and social consensus to invest in the infrastructure. Finally, to protect employees’ health from the negative health effects of rapid restructuring and downsizing, and to minimize the scale of exploited including precarious, informal, and slave labor, a successful international collaboration must be based on the establishment agencies with real power to influence government legislation, monitoring, and proper enforcement.

Bibliography:

- After Chen MA, Vanek J, and Carr M (2004) Mainstreaming Informal Employment and Gender in Poverty Reduction Women and Men in the Informal Economy. pp. 10–33. Ottawa, Canada: The International Development Research Centre.

- Ahn N and Mira P (2001) Job bust, baby bust? Evidence from Spain. Population Economics 14: 5005–5021.

- Amick B, Kawachi I, Coakley E, Lerner D, Levine S, and Colditz G (1998) Relationship of job strain and iso-strain to health status in a cohort of women in the United States. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health 24(1): 54–61.

- Anitua C and Esnaola S (2000) Changes in social inequalities in health in the Basque Country. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 54(6): 437–443.

- Appelbaum S and Donia M (2001) the realistic downsizing preview: A multiple case study, Part 1: The methdology and results of data collection. Career Development International 6: 128–148.

- Appleton S and Song L (1999) Income and Human Development at the Household Level: Evidence from six Countries. Oxford: University of Oxford Press.

- Ashford SJ, Lee C, and Bobko P (1989) Content, causes, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Academy of Management Journal 32(4): 803–829.

- Asian Development Bank (2004) Asian Development Outlook 2004, Foreign Direct Investment in Developing Asia. New York: Asian Development Bank by the Oxford University Press.

- Avison W (2001) Unemployment and its consequences for mental health. In: Marshall V, Heinz W, Kruger H, and Verma A (eds.) Restructuring Work and the Life Course, pp. 177–200. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Axelrod WL and Gavin JF (1980) Stress and strain in blue-collar and white-collar management staff. Journal of Vocational Behavior 17: 41–49.

- Bartley M (1999) Measuring women’s social position: The importance of theory. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 53(10): 601–602.

- Beale N and Nethercott S (1988) Certified sicknesss absence in industrial employees threatened with redundancy. British Medical Journal 296: 1508–1510.

- Benach J, Amable M, Muntaner C, and Benavides F (2002) The consequences of flexible work for health: Are we looking at the right place? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56: 405–406.

- Benavides FG, Benach J, Diez-Roux AV, and Roman C (2000) How do types of employment relate to health indicators? Findings from the Second European Survey on Working Conditions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 54(7): 494–501.

- Bielenski H (1999) New patterns of employment in Europe. WHO Regional Publications European Series 81: 11–30.

- Blunch N-H, Canagarajah S, and Raju D (2001) The Informal Sector Revisited: A Synthesis Across Space and Time. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Booth AL, Marco F, and Jeff F (2002) Temporary Jobs: Stepping stones or dead ends? The Economic Journal 112: f189–f213.

- Bourdouxhe M and Toulouse G (2001) Health and Safety Among Film Technicians Working Extended Shifts. Journal of Human Ergology 30: 113–118.

- Brand J (2005) Enduring Effects of Job Displacement on Career Outcomes The Humanities and Social Sciences. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin.

- Brown C, Arnetz B, and Petersson O (2003) Downsizing within a hospital: Cutting care or just costs. Social Science and Medicine 57(9): 1539–1546.

- Budros A (1997) The new capitalism and organizational rationality: The adoption of downsizing programs 1979–1994. Social Forces 76(1): 229–250.

- Buono A and Bowditch J (1989) The Human Side of Mergers and Acquisitions: Managing Collisions Between People Cultures and Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- Burke R and Greenglass E (1999) Work-family conflict, spouse support, and nursing staff well-being during organizational restructuring. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 4(4): 327–336.

- Burton WN, Conti DJ, Chen CY, Schultz AB, and Edington DW (2001) The impact of allergies and allergy treatment on worker productivity. Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine 43(1): 64–71.

- Bussing A (1999) Can control at work and social support moderate psychological consequences of job insecurity? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 8: 219–242.

- Campbell I (1997) Beyond unemployment: The challenge of increased precariousness in employment. Just Policy 11: 4–20.

- Chatterjee S and Kuhnhenn J (2001) House Approves No-Slavery Labelson Chocolate Products Despite Industry Protest. Washington, DC: Knight-Ridder Washington Bureau.

- Chaykowski RP (2005) Non-standard work and economic vulnerability. Vulnerable Workers Series, In: No 13, pp. 1–67. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks Incorporation.

- Chen MA, Vanek J, and Carr M (2004) Mainstreaming Informal Employment and Gender in Poverty Reduction Women and Men in the Informal Economy, pp. 10–33. Ottawa, Canada: The International Development Research Centre.

- Cheng Y, Chen C, Chen C, and Chaing T (2005) Job insecurity and its association with health among employees in the taiwanese general population. Social Science and Medicine 61: 41–52.

- Cole DC, Ibrahim S, and Shannon H (2005) Predictors of work-related repetitive strain injuries in a population cohort. American Journal of Public Health 95(7): 1233–1237.

- Daza JL (2005) Social Dialogue, Labour Law and Labour Administration Department Informal Economy, undeclared Work and Labour Administration. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office, Paper No. 9.

- De Witte H (1999) Job insecurity and psychological well-being: review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 8: 155–177.

- Dekker SWA and Schaufeli WB (1995) The effects of job insecurity on psychological health and withdrawal: A longitudinal study. Australian Psychologist 30(1): 57–63.

- Devereux JJ, Vlachonikolis IG, and Buckle PW (2002) Epidemiological study to investigate potential interaction between physical and psychosocial factors at work that may increase the risk of symptoms of musculoskeletal disorder of the neck and upper limb. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 59(4): 269–277.

- Domenighetti G, D’Avanzo B, and Bisig B (1999) Health Effects of Job Insecurity Among Employees in the Swiss General Population. Lausanne: University of Lausanne.

- Dunlop S, Coyte PC, and McIsaac W (2000) Socio-economic status and the utilisation of physicians’ services: Results from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. Social Science and Medicine 51(1): 123.

- Farr B (1996) Understaffing: A risk factor for infection in the era of downsizing. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 17: 147–149.

- Fassa AG (2003) Health benefits of eliminating child labour. In: Paper IIW (ed.) International Program on the Elimination of Child Labor. Paris: International Labour Office.

- Feldman DC (1995) The impact of downsizing on organizational career development activities and employee career development opportunities. Human Resource Management Review 5(3): 189–221.

- Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, Stansfield S, and Smith GD (1995) Health effects of anticipation of job change and non-employment: Longitudinal data from the Whitehall II Study. British Medical Journal 311: 1264–1269.

- Ferrie J, Shipley M, Marmot M, Stansfeld S, and Smith DG (1998a) An uncertain future: The health effects of threats to employment security in white-collar men and women. American Journal of Public Health 88: 1030–1036.

- Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, Stansfield S, and Smith GD (1998b) The health effects of major organisational change and job insecurity. Social Science and Medicine 46(2): 243–254.

- Ferrie J, Martikainen P, Shipley M, Marmot M, Stansfeld S, and Davey Smith G (2001a) Employment status and health after privitisation in white collar civil servants: Prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal 322: 647–651.

- Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, Martikainen P, Stansfield SA, and Smith GD (2001b) Job insecurity in white-collar workers: Toward an explanation of associations with health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 6(1): 26–42.

- Ferrie J, Shipley M, Stansfeld S, and Marmot M (2002) Effects of chronic job insecurity and change in job security on self-reported health minor psychiatric morbidity physiological measures, and health related behaviours in British civil servants: The Whitehall II Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56: 450–454.

- Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Newman K, Stansfeld SA, and Marmot M (2005) Self-reported job insecurity and health in the Whitehall II study: Potential explanations of the relationship. Social Science and Medicine 60(7): 1593–1602.

- Fox G and Chancey D (1998) Sources of economic distress: Individual and family outcomes. Journal of Family Issues 19: 725–749.

- Free The Slaves (2004) Hidden Slaves Forced Labor in the United States. Human Rights Center: Berkeley. University of California Berkeley.

- Fridkin S, Pear S, Williamson T, Galgiani J, and Jarvis W (1996) The role of understaffing in central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infections. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 17: 150–157.