View sample undernutrition research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a health research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Introduction

It must be remembered that privation of food is very reluctantly borne, and that as a rule great poorness will only come when other privations have preceded it. Long before insufficiency of diet is a matter of hygienic concern, long before the physiologist would think of counting the grains of nitrogen and carbon which intervene between life and starvation, the household will have been utterly destitute of material comfort; clothing and fuel will have been even scantier than food… . The home, too, will be where shelter can be cheapest bought; in quarters where commonly there is least fruit of sanitary supervision, least drainage, least scavenging, least suppression of public nuisances, least or worst water supply.. . . And while the sum of them is of terrible magnitude against life, the mere scantiness of food is in itself of very serious moment. Karl Marx, Das Kapital (1867: 726)

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Undernutrition and lack of food, as Karl Marx noted when describing the plight of the English working classes more than 150 years ago, are the culmination of numerous deprivations. Even today risk factors for infections and undernutrition are concentrated amongst the poor. Children of the poor are more likely to be born with low birth weight to mothers who are undernourished, and are less likely to receive energy-rich complementary food or iodized salt. The only advantage they have, and this is only in poorer countries, is that they are more likely to be breastfed, and for longer, than their richer counterparts (although HIV is now eroding this in some regions). Poorer children also live in environments that predispose them to illness and death. They are more exposed to diarrhea pathogens, being less likely to live in households with safe water or sanitation, and more likely to contract pneumonia, being exposed to indoor air pollution – a result of the greater reliance on burning coal and biomass fuel (wood, animal dung) for cooking and heating, coupled with inadequate ventilation.

The Significance Of Undernutrition

There is now a solid body of evidence that underweight and micronutrient deficiencies significantly increase the risk of death in children. Pooled analysis of community cohort studies estimates that underweight is the underlying condition responsible for about 53% of all childhood deaths (Pelletier et al., 1995). About 35% of all childhood deaths are due to the effects of underweight on diarrhea, pneumonia, measles, and malaria. Similarly, intervention studies have established that children over 6 months of age with vitamin A deficiency have a 23% increased risk of dying in childhood and those with zinc deficiency a 15% increased risk (Black, 2003). A recent systematic review of risk factors for premature mortality quantified the total loss due to undernutrition and other underlying risk factors:

Despite disaggregation into underweight and micronutrient deficiency (which are not additive) and methodological changes, undernutrition has remained the single leading global cause of health loss, with comparable contributions in 1990 (220 million DALYs; 16% for malnutrition) and 2000 (140 million DALYs; 9.5% for underweight; 2.4%, 1.8%, and 1.9% for iron, vitamin A, and zinc deficiency, respectively; 0.1% for iodine-deficiency disorders).

Leading causes of burden of disease in all high-mortality, developing regions were childhood and maternal undernutrition – including underweight (14.9%), micronutrient deficiencies (3.1% for iron deficiency, 3.0% for vitamin A deficiency, and 3.2% for zinc deficiency), unsafe sex (10.2%), poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (5.5%), and indoor smoke from solid fuels (3.6%). (Ezzati et al., 2002: 1355)

The Extent Of Undernutrition

Unfortunately the progress in reducing hunger and undernutrition remains too slow in many parts of the world and has actually reversed for many populations. According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), every day 799 million people in developing countries – about 14% of the world’s population go hungry. Whilst there were reductions in the number of chronically hungry people in the first half of the 1990s, between 1995 and 1997, the number increased by over 18 million. Similarly the number of undernourished people actually increased by 4.5 million per year in the late 1990s. Approximately 175 million children under 5 years of age are estimated to be underweight, 32% of preschool children are stunted, 16% of birth weights are below 2.5 kg, and 243 million adults are severely malnourished. Two billion women and children are anemic, 250 million children suffer from vitamin A deficiency, and 2 billion people are at risk from iodine deficiency. In sub-Saharan Africa the proportion and absolute number of malnourished children has actually increased over the past decade. Eastern Africa is the sub-region experiencing the largest increases in prevalence and numbers of underweight children, increasing to around 36% by 2005. Findings for stunting, or extreme shortness of stature – which reflects long-term undernutrition – and extreme thinness, or wasting, are similar.

Causes Of Undernutrition

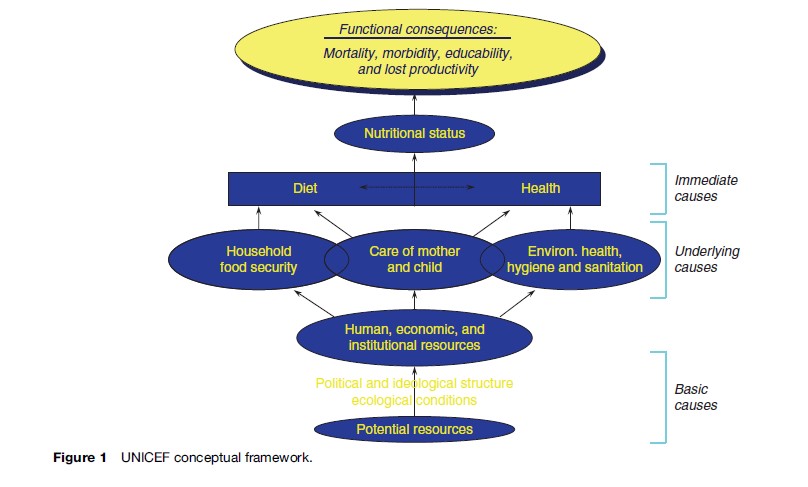

An explanation often proffered for differences in levels of stunting between populations is genetic differences. The rapid increase in height among second-generation immigrants, such as the Japanese to the United States, as well as significant rises in secular trends of average height in countries that have recently undergone rapid development, is just some of the vast body of evidence that environmental factors are far more important. This is recognized in UNICEF’s widely used conceptual framework that displays the multifactorial nature of the causes of undernutrition (Figure 1). It draws attention not just to the immediate causes such as inadequate food and nutrients and frequent illness, but also to how these in turn are related to access to food through household food security, the environment in which people live, and the caring practices performed. The conceptual framework is essential in understanding the paradox of the poor progress toward reducing levels of malnutrition in many parts of the world, even though this has coincided with the greatest expansion in crop and food production in human history. There is now more than enough food to feed everybody on the planet with a doubling in food production over the last 40 years. However, it is clear that many millions of people are not sharing in the benefits of this increased production. This research paper focuses on four more distal or social determinants of undernutrition, especially in sub-Saharan Africa: low levels of female education, globalization of trade and agriculture, HIV/ AIDS, and inappropriate social sector reform.

Female Education

Female education leads to better health outcomes, even after controlling for the higher household income that usually goes hand-in-hand with higher levels of education. For example, education (especially that of women) is strongly associated with the level of health service use, the type of provider, the choice of private versus public provider, dietary and child-feeding practices, and sanitary practices. Overall, this can have a significant impact on child health. In Sri Lanka, for example, under-5-years mortality rate was over 30 per 1000 live births among mothers with no education or only primary schooling, but less than 20 per 1000 among mothers with above primary schooling. It is probable that this relationship exists because educated women are better able to deal with their children’s illness episodes; they are more likely to take them to modern health facilities for treatment, follow health providers’ instructions carefully, and take their children back if medication does not seem to be working.

It is not just general education, but also health-specific knowledge that matters. A recent study in Morocco (Glewwe, 1999) suggests that, by themselves, general numeracy and literacy levels do not – at least in Morocco – lead to better child nutrition. What enables educated women to achieve higher levels of nutrition for their children is that they are able to use their general knowledge and skills to acquire health-specific knowledge. Closely related to female education is women’s power. Women who have relatively little control over household resources are less likely to receive antenatal care, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy (Beegle et al., 2001).

Globalization, Agriculture, And Trade

In less than 4 decades sub-Saharan Africa has been transformed from a net exporter of food to a continent now heavily dependent on food imports. Africa accounted for 18% of world imports in 2001 (up from 8% just 15 years previously) (Beintema, 2002). This was caused by a sharp decline in per capita output in sub-Saharan Africa. Agricultural productivity per worker for the region as a whole fell by about 12% from US$424 in 1980 to an estimated US$365 per worker (constant: 1995 US$) in the late 1990s (World Bank, 2002). Although overall agricultural output has risen, this has been the result of expansion in the area under cultivation. The UN Millennium Development Goals (MDG) Hunger Task Team (2003) Interim Report summarizes the consequences:

Expanding the area under food production is inherently unsustainable, as the supply of new lands in densely populated areas of Africa is largely exhausted or must be maintained as natural systems for biodiversity conservation and other ecological services. The first effect in Africa and elsewhere in the tropics has been to expand into land that was previously available for fallows. Leaving land fallow allows land under cultivation the necessary time to recover from the effects of the crops taking nutrients from the soil. As a result of the reduction or elimination of fallows, soil fertility has fallen dramatically in many places, and yields are reducing with time. As the land becomes exhausted, there develops a serious tendency to continually subdivide land among family members, which leads to holdings too small to produce a family’s food. (World Bank, 2003: 52)

Significantly, the yields of most important food grains, tubers, and legumes (maize, millet, sorghum, yams, cassava, and groundnuts) in most African countries are no higher today than in 1980. The environmental impacts of deforestation and drought, floods, and the loss of topsoil are being compounded by the lack of investment. Only about 4.2% of land under cultivation in Africa is irrigated. This compares with 14% in Latin America and the Caribbean, a region with similar population densities and resource endowments (World Bank, 2003). Fertilizer application is 15% lower today than in 1980. The number of tractors per worker is 25% lower than in 1980 and the lowest in the world. Africa’s share of total world agricultural trade fell from 8% in 1965 to 3% in 1996 (World Bank, 2003).

For years, public investment in agriculture has been falling, not rising. In countries where 20 to 35% of the population are defined as food insecure, agricultural spending averaged 7.6% of the national budget in 1992 and 5.2% in 1998. For countries with more than 35% of their population suffering food insecurity, agricultural spending in 1992 was 6.8% and declined to 4.9% in 1996, the last year for which data are available (IFPRI, 2004).

The dramatic decline in investment in the rural economy is leading to increasing household food insecurity, not just in sub-Saharan Africa but also in India – recent survey data show that the average Indian family of four has reduced annual consumption of food grains by 76 kg compared with just 6 years ago, and this has now reached levels last seen just after independence (Persaud and Rosen, 2003). This dramatic fall is also a result of the collapse in rural employment and incomes as liberalization of the agricultural sector leads to the buying out of small farmers.

This process has been accelerated by the undermining of the prices of agricultural commodities and products because of the massive farming subsidies in the developed countries. In the European Union, the average dairy cow has a bigger annual ‘income’ than most people in the world. In the United States the 2002 Farm Bill recently authorized the paying out of US$180 billion over a 10-year period as ‘emergency measures,’ mainly in sup-port of staple cereal crops. The Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy has calculated that United States subsidies mean that major crops are put on the international market at well below their production costs: wheat by an average of 43% below the cost of production, soybeans at 25% below, cotton at 61% below, and rice at 35% below. This depression of commodity prices is having a devastating effect on farmers in developing countries. Research by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) shows that subsidies to agriculture in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, which totaled US$311 billion in 2001 (or US $850 million per day), are displacing farming in the developing countries, thereby costing the world’s poor countries about US$24 billion per year in lost agricultural and agro-industrial income. The deteriorating terms of trade for developing countries are starkly expressed by commodity prices. In 2000, prices for 18 major export commodities were 25% lower in real terms than in 1980 and yet retail prices in the developed world continue to rise. For eight of these commodities, the decline exceeded 50%.

Reconciling the rhetoric of reliance upon the ‘free’ market for food security with the huge subsidies given to large commercial farmers in the north can only be done through recognizing the different interpretations of food security applied. Contrast President George W Bush’s interpretation of food security for the United States with the urging of his officials to developing countries to rely upon American exports:

It’s important for our nation to build – to grow foodstuffs, to feed our people. Can you imagine a country that was unable to grow enough food to feed the people? It would be a nation subject to international pressure. It would be a nation at risk. And so when we’re talking about American agriculture, we’re really talking about a national security issue. (President Bush, quoted in McMichael, 1994: 12)

But it is a different story for developing countries where there has been a fundamental shift away from national food sufficiency – world wheat and rice imports have grown from 46 and 6.5 million metric tonnes, respectively, in 1961 to 120 and 27 million metric tonnes, respectively, in 2001 (World Bank, 2003). In many cases governments have been powerless to reverse this state of affairs as IMF/World Bank imposed policies, such as removing subsidies for fertilizer or charging user fees for dipping of cattle, directly impact the cost of agricultural inputs. Many developing countries are now at the mercy of world food grain prices that in turn can be extremely volatile since production is now so concentrated. There are real fears that grain prices may further escalate as increasing amounts of cereals are dedicated to bio-fuel production. This might benefit a few farmers in developing countries but for the majority of the poor these price rises will further increase household food insecurity.

The wider liberalization of trade (and financial markets) has accelerated during the past decade and a half and is clearly impacting negatively on the living standards and diets of the poor in some countries. For example, textiles and clothing industries in Zambia, the poultry sector in Ghana, and corn cultivation in Mexico have been decimated by the lowering of trade barriers with resultant social dislocations. In Mexico, 700 000 agricultural jobs have been lost with rural poverty rates rising to more than 70% and infant mortality rates among the poor increasing (Henriques and Patel, 2004).

HIV/AIDS

HIV, nutrition, and food security interact at a number of different levels – biological, individual, and community. At the biological level it is well established that good nutrition plays a critical role in the ability of the individual’s immune system to withstand and respond to infections. HIV is no exception. At the individual level poor nutritional status (especially from a young age) leads to reduced physical and intellectual capacity, ultimately leading to reduced earning potential. Poverty is well recognized as an important factor in increasing vulnerability to HIV. Poor women are especially vulnerable. Finally, communities with poor food security are more likely to be engaged in high-risk strategies such as increased migration and commercial sex and to have decreased access to health-care services. They are therefore at increased risk of spreading or contracting HIV. Similarly, HIV erodes social capital and traditional coping mechanisms within communities, thus increasing food insecurity. For example, one common coping strategy is to grow and consume foods that are easier to cultivate and cheaper to purchase, but these also tend to be nutritionally poorer foods (such as starchy foods). Many households also skip meals. Their vulnerability is increased by a reduction of their capacity to respond both at a biological level and at an individual and community level.

The role that HIV/AIDS is playing in undermining development in the African region is shown by the experience of the recent climatic changes compared with the drought in 1991–92. The 1991–92 drought was far more severe and yet there were far fewer starvation deaths reported. Through its devastating impact on economically active members of society the epidemic is eroding the capacity of many communities to cope with the usual challenges that poverty brings. Young people are inheriting debts and having to increase cultivation to feed more dependants without the luxury of having gone through an apprenticeship in agricultural techniques and with less opportunity for accessing credit and knowledge through community and state institutions. In Zimbabwe, a study found that output on small-holder farms shrank by 29% for cattle, 49% for vegetables, and 61% for maize if the household had suffered an AIDS-related death (UNAIDS/ WHO, 2003). Overall, in maize production, there was a decline of 54% of the harvested quantity. The amount of land planted to cotton decreased by about 34% and marketed output by 47%; while groundnut and sunflower production experienced an average decline of 40%.

Even though HIV infects all sectors of society it is fairly well established that once again it is the poorest that are the most susceptible and have the highest rates of infection. HIV/AIDS has a greater economic impact on poor households than on better-off ones because it forces them to draw on their meager assets to cushion the shock of illness and death; and households with fewer assets are likely to have more difficulty coping than households with more assets. In particular, it is women who are at increased risk. Overall, about twice as many young women as men are infected in sub-Saharan Africa. Not only do women have an increased physiological risk of HIV infection but this is compounded by economic need, lack of employment opportunities, poor access to education, training, and information, and local traditions. In rural areas, women tend to be even more disadvantaged due to reduced access to resources and services. A combination of these factors prevents women from having choices, especially choices about sexual risk and family health.

It is poor women in particular who are bearing the brunt of HIV/AIDS. They are also responsible for 50 to 80% of food production, including the most labor-intensive work, such as planting, fertilizing, irrigating, weeding, harvesting, and marketing. Their work also extends to food preparation, as well as nurturing activities. The impact on them of HIV/AIDS is multilayered. It falls on poor women to care for sick spouses, children, and relatives while continuing to strive for household food security. Quite often this is untenable: a survey carried out in two Zimbabwean districts in 2000 revealed that two-thirds of households that had lost a key adult female had disintegrated and dispersed.

Social Sector Reforms

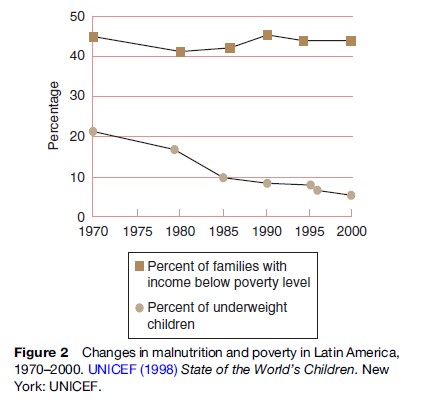

Food security level or poverty alone does not explain why many countries and populations, however poor, have managed significant reductions in malnutrition before there were similar reductions in poverty. For example, in a comparison among Sri Lanka, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand, all countries with similar levels of poverty in the 1970s, Sri Lanka and Thailand showed rapid improvement in nutrition in the 1980s to 1990s. Indonesia showed slower but consistent improvement, and the Philippines showed little progress (Mason, 2001). At the regional level, malnutrition in Latin America decreased from an estimated 21% in 1970 to 7.2% in 1997, while the rate of poverty (measured by income level) decreased only slightly over the past three decades, from 45% in 1970 to 44% in 1997 (Figure 2). These trends show that the reduction of malnutrition is not solely dependent on increases in income. In Latin America, the gains in reducing malnutrition are attributed, at the underlying level, to good care practices (such as improved complementary feeding) and access to basic health services, including family planning and water/sanitation services; and, at the basic level, to women’s empowerment in terms of their education and the cash resources they control (UNICEF, 1998).

Whatever the capacity of the state, communities and families in many developing countries have been seriously undermined as a result of the structural adjustment programs (SAPs) that have been imposed on developing countries. These have usually involved reducing the budget deficit through a combination of cuts in government spending (e.g., reductions in staff numbers); trade liberalization, including removal of price controls; deregulation of foreign trade, investment, and production; phased removal of subsidies including on basic foods; devaluation of the local currency; and enforcement of cost recovery in the health and education sectors.

These economic reforms have been associated with severe declines in economic and health welfare, and hence nutrition, in many countries, with greatest impact on the poorest people. In the Congo, for instance, the 1994 devaluation, prescribed by its SAP, resulted in increasing food prices and a subsequent negative impact on the nutritional status of children. In Zambia the wages of public sector employees collapsed to a quarter of their 1975 levels in the early 1990s. A recent review of the impact of SAPs on health and nutrition, by World Bank analysts, concluded: ‘‘The majority of studies in Africa, whether theoretical or empirical, are negative towards structural adjustment and its effects on health outcomes’’ (Breman and Shelton, 2001: 15).

Conclusion

When considering the social determinants of undernutrition it is necessary to bear in mind the interconnections between these different determinants or causes. For example, in reading the literature on the impact of HIV on household food security, it is easy to forget that the epidemic does not just hit the most vulnerable households the hardest, but also the countries that have suffered the most with respect to new global trade and financial organization. The focus in the literature is usually on how HIV/AIDS is destroying households and communities within African states too corrupt or incapacitated to help. It is portrayed as an African problem. However, the underlying vulnerability of these countries, communities, and households is inextricably linked to the deteriorating terms of trade with the rest of the world, and in particular the spectacular decline in commodity prices. Similarly, the impacts of trade liberalization (with resulting declines in tax revenue from trade tariffs) and the terrible effect of HIV/AIDS on civil servants substantially reduces the capacity of the state to respond to the increasing vulnerability of large sections of its population.

There is an urgent need to raise the awareness of the health and economic impact of poor nutrition among senior policy makers, especially those in the Finance Ministries who make key resource allocation decisions. Nearly all countries have also made public commitments toward achieving the Millennium Development Goals. These will only be realized if serious investment in nutrition is made.

Bibliography:

- Beegle K, Frankenberg E, and Thomas D (2001) Bargaining power within couples and use of prenatal and delivery care in Indonesia. Studies in Family Planning 32(2): 130–146.

- Beintema N and Stads GJ (2002) Investing in Sub-Saharan African Agricultural Research: Recent Trends. 2020 Conference Brief 8. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Black RE (2003) Zinc deficiency, infectious disease and mortality in the developing world. Journal of Nutrition 133(5, supplement 1): 1485S–1489S.

- Breman A and Shelton C (2001) Structural Adjustment AND Health: A Literature Review of the Debate, Its Role Players and the Presented Empirical Evidence. Working Paper No. WG6, p. 6. WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Ezzati M, Lopez A, Rodgers A, et al. (2002) Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. The Lancet 360: 1–14.

- Glewwe P (1999) ‘Why does mothers’ schooling raise child health in developing countries?’ Journal of Human Resources 34(1): 129–144.

- Henriques G and Patel R (2004) NAFTA, Corn, and Mexico’s Agricultural Trade Liberalization. America’s Program. Silver City, NM: Interhemispheric Resource Center.

- International Food and Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) (2004) How Much Does It Hurt? Impact of Agricultural Policies on Developing Countries. Washington, DC: International Food and Policy Research Institute.

- Mason JB (2001) Measuring Hunger and Malnutrition. New Orleans, LA: Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine.

- McMichael P (1994) The Global Restructuring of Agro-Food Systems. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA Jr, Schroeder DG, et al. (1995) The effects of malnutrition on child mortality in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 73: 443–448.

- Persaud S and Rosen S (2003) India’s consumer and producer price policies: Implications for food security. Food Security Assessment February: 32–39.

- UNAIDS/WHO (2003) AIDS Epidemic Update. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS/WHO.

- UNICEF (1998) State of the World’s Children. New York: UNICEF.

- World Bank (2002) From action to impact. Discussion Paper, the Africa Region’s Rural Strategy: Rural Development Operations. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- World Bank (2003) From action to impact. Discussion Paper, the Africa Region’s Rural Strategy. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2003) The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2003: Monitoring Progress Towards the World Food Summit and Millennium Development Goals. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (2004) U.S. Dumping on World Agricultural Markets. Minneapolis, MN: Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy.

- Pinstrup-Andersen P and Pandya-Lorch R (eds.) (2001) The Unfinished Agenda: Perspectives on Overcoming Hunger, Poverty, and Environmental Degradation. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- UNAIDS (2002) AIDS Epidemic Update, December 2002. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- UNAIDS (2003) AIDS and Female Property/Inheritance Rights. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

- World Health Organization (2002) Reducing risks, promoting healthy life.

- World Health Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.