View sample women’s health research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a health research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Introduction

A report in 2004 by the Secretariat of the World Health Organization summarized threats to women’s health in three broad categories of vulnerability:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

- Inequities related to gender: Inequities related to gender manifest in many forms. For example, they may include the consequences of lower familial investment for female children, such as inadequate nutrition, poorer access to health care, or reduced educational and job training opportunities. They include the impact of experiencing discrimination or living in conditions of low social status, which may affect physical and mental health outcomes. Moreover, gender inequities may be experienced directly through reduced control over one’s body, potentially resulting in unprotected, unwanted, or forced sexual intercourse or violence.

- Adolescents’ exposure to risk: Adolescents’ exposure to risk is a second significant area of women’s vulnerability. Many cultures limit adolescent access to information that may be needed to protect a teen’s reproductive and sexual health. Adolescents also have reduced economic resources, which affects their ability to access quality health care, and they are especially vulnerable to stigma and violence.

- Inequities related to poverty and poor access to health care: Women’s health is greatly affected by inequities related to poverty and poor access to health-care services. Many women most in need of quality care live in settings with the least resources, medical personnel, and facilities. Access to health care is influenced by distance from services, lack of transport, cost of services, and discriminatory treatment of users.

Women live longer than men, but have higher morbidity. In this research paper, we examine the interrelationships between women’s living conditions – poverty, poor access to health care, living in low-resource areas, and disadvantages related to young age as well as gender inequities – on the distribution of health and illness worldwide. Whether examining reproductive health outcomes or chronic or infectious diseases, social and institutional environments affect the incidence and course of disease in women, their access to health care, and their morbidity.

Women’s Health

According to estimates from the United Nations, 81% of the world’s 6.5 billion people live in less developed regions. Population growth is expected to increase rapidly in the coming decades, so that by the year 2050, 86% of the world’s population will be living in developing regions. The implications for women’s health are profound because health outcomes and health-care access are overwhelmingly poorer in developing countries.

Women comprise 49.7% of the world’s population, but 70% of the world’s poor. Life expectancy for women exceeds that of men in all regions of the world. This discrepancy is greatest in developed nations where women live an average of 7.4 years longer than men (79.3 vs. 71.9 years). In the least developed nations, where life expectancy is much lower, women outlive men an average of 2 years (52.0 vs. 50.1 years). The HIV epidemic has had an important impact on life expectancy statistics, with life expectancy for men now exceeding that of women in high prevalence countries, such as Kenya, Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. This phenomenon will spread to other HIV high-prevalence nations in the coming years.

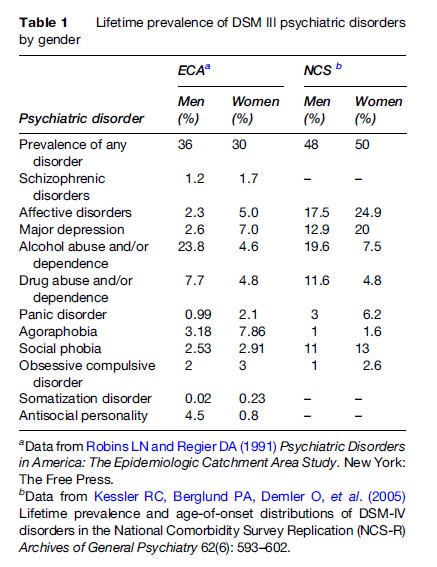

A familiar paradox of women’s health is that women live longer than men, but have poorer health. Disparities in self-reported general health and physical functioning arise in early adulthood and persist across the life span. Table 1 summarizes the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in women. Chronic conditions, such as heart and cerebrovascular diseases (CVD), dominate the mortality statistics, whereas infectious diseases, mental health, and reproductive conditions are leading sources of morbidity in women. When measuring the impact of diseases using disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs; a measure that summarizes the total years of healthy life lost to disability and premature death), the leading burdens for women include lower respiratory tract infections, HIV/ AIDS, unipolar depressive disorders, and maternal conditions. Infectious diseases account for 22.8% of DALYs compared with 8% for chronic or noncommunicable disease. Other conditions, such as unipolar depressive disorders, cataracts, hearing loss, and osteoarthritis, although not major contributors to mortality statistics, are leading sources of disability when measured using the years lost to disability method.

The Role Of Chronic Diseases in Women’s Health

Women’s health, especially in developing nations, has been predominantly defined as reproductive health, as a result, the impact of chronic disease has been overlooked. Chronic disease is an important source of morbidity and mortality among young and old women in both developed and developing nations.

As seen in Table 1, chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes, are important contributors to global statistics of women’s morbidity and mortality. In fact, data from 1999 found that, although chronic diseases were responsible for only one in five deaths in Africa, they were responsible for more than half of deaths in all other regions (Brands and Yach, 2002). Chronic disease affects women’s health across the life span. Raymond and colleagues looked at nine studies of causes of death for women in developing nations and found that chronic disease deaths (due to CVD, cancer, or diabetes) were a significant proportion of deaths among women 15–44 years of age in all nine studies examined (Raymond et al., 2005). In fact, chronic disease accounted for a larger proportion of deaths than HIV and reproduction in eight of the nine countries in both young and old women. Further, the percentage of female deaths due to chronic disease did not appear to be associated with the level of development of the nations.

Heart Disease

Cardiovascular disease is an important source of morbidity and mortality for adult women worldwide. In all regions of the globe except for sub-Saharan Africa the number of deaths due to cardiovascular disease exceed those caused by infectious and parasitic diseases. Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of death among women, accounting for 12.5% of all deaths and considerable morbidity. Similarly, hypertension is the cause of 1.8% of deaths. Increases in behaviors associated with cardiovascular disease, like dietary changes, tobacco use, obesity, and physical inactivity, lead experts to forecast significant increases in the rates of cardiovascular disease by the year 2020 (Husten, 1998; Yusuf et al., 2001) This increase is expected to be particularly pronounced for women living in developing nations. Mortality from ischemic heart disease will increase 29% for women in developed nations and 120% for women in developing nations.

Hypertension or elevated blood pressure is a major modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease. One in four women globally have hypertension, and this percentage is anticipated to increase to almost one in three in the coming decades. The prevalence of hypertension varies widely, but is common among women in developed and developing nations. A meta-analysis of published papers on hypertension that included 33 developing and 4 developed nations found that, in 41% of populations studied, women had higher rates of hypertension than men in their same country and 45% of developing nations had higher rates of hypertension than U.S. females (Fuentes et al., 2000) The prevalence of hypertension was higher among urban populations and in nations with higher gross national products per capita. Awareness of hypertension diagnosis, access to appropriate treatment, and successful control of blood pressure varied considerably, but in general, women fared better than their male counterparts.

Cancer

Cancer is an important source of morbidity and mortality for women worldwide. And, unlike many health conditions that are important to women’s health, cancer has higher incidence and mortality rates in developed nations. The age-standardized incidence rate in developed nations is 228.0 per 100 000 women compared with 128.8 per 100 000 women in developing nations. Similarly, the age-standardized mortality rate in developed nations is 102.5 per 100 000 compared with 83.1 in developing nations for all cancers. Cancer causes 1 in 20 deaths in Africa, 1 in 14 deaths in Eastern Mediterranean and South East Asia, and 1 in 5 deaths in the American region, Europe, and Western Pacific (Brands and Yach, 2002).

The most prevalent sites for cancer differ in developing versus developed nations. In developed nations, cancers of the breast, colon and rectum, and lung have the highest incidence and mortality rates. In developing nations, breast cancer is again the most common site for cancer, but the incidence and mortality rates are significantly lower than in developed nations. The second two most common sites in developing nations are the cervix and the stomach. Breast, colorectal, and lung cancers have well-known associations with tobacco use, diet, and physical inactivity. Although the incidence of cancer has been decreasing in developed nations, it is anticipated to increase dramatically by 2020. This increase is predominantly attributed to the adoption of ‘Western’ personal behaviors, such as tobacco use.

Similarly cervical and stomach cancers are related to individual behaviors (e.g., sexual activity or diet) and are also strongly related to access to preventive screening and treatment. For example, the availability of treatment for H. pylori significantly reduces the incidence of stomach cancer. In the case of cervical cancer, for which four of five new cases are diagnosed in developing nations, access to screening is essential in the reduction of incidence. Although systematic screening has dramatically reduced the incidence of cervical cancer in developed nations, a study by the World Health Organization found that screening had limited impact on cervical cancer incidence in developing nations. Developing nations are often faced with the absence of screening programs, inadequate funding, and lack of quality health-care professionals and facilities. Finally, the incidence of cervical cancer may be correlated with the degree of women’s control over their own bodies and fertility. The ability to negotiate the use of barrier contraceptives and to regulate one’s extent of sexual activity can have profound effects of the transmission of human papilloma virus.

Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is the tenth leading cause of death in women globally and an important source of morbidity. Complications of diabetes may manifest as either microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy), or macrovascular (hypertension and hyperlipidemia) endpoints, or both. Although diabetes itself is not a modifiable risk factor for these complications, improved glycemic control has been shown to delay the onset and slow the progression of microvascular complications, such as diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy, and possibly reduce the number of cardiovascular events.

The prevalence of diabetes has been increasing in both developing and developed nations and is expected to double in the next 25 years. Estimates are that between 500 000 and 1.5 million women die as a result of diabetes each year. Of these deaths, roughly 75% occurred in women living in developing nations. Diabetes is also an important contributor to disability and in 2002 was responsible for almost 4 million years lost to disability. Unlike many other health conditions, the overall attributable burden associated with disability is greater for women in developed nations.

The Role Of Reproductive Health

Reproductive health services are essential needs for women, most acutely during their childbearing years. However, in developing and some developed nations, access to health care is poor or nonexistent. Several gender-related constraints interfere with women’s ability to access reproductive health services in developing countries. Women are often not free to make decisions about their reproductive health and may not have the freedom to travel to health facilities or resources to pay for needed services. Adolescent and unmarried women are often prevented from receiving reproductive health services by strict beliefs about sexuality and sexual activity.

Fertility And Fertility Control

Fertility is the total number of births that each woman would have during her lifetime if she bore children at current fertility rates. The number of births and age at first birth have lasting socioeconomic consequences in the lives of women. High fertility and early childbearing are associated with reduced earning potential, reduced educational and job training opportunities, increased likelihood of divorce or single parenthood, and a greater risk of living in poverty. In 2000 the total fertility rate was 2.7 births per woman worldwide. Most births occur in developing nations. The fertility rate was:

- 6 in developed nations

- 0 in developing nations

- 4 in the least developed nations

- 7 in sub-Saharan Africa.

Between 1990 and 2000, fertility decreased dramatically, in part due to increased contraceptive use. Declines averaged:

- Overall – 16%

- Largest decline – 26% in the Middle East/North

Africa

- Smallest decline – 10% in sub-Saharan Africa.

Contraceptive Use

Worldwide contraceptive prevalence (the percentage of married women currently using contraception) was approximately 58% in 1993, with average levels higher in more developed nations (68–70%) than in developing nations (55–58%) according to the United Nations and Population Research Bureau (2005). The prevalence of contraceptive use was lowest in Africa (20%) with western Africa being the lowest prevalence region (8%). In contrast, eastern Asia had the highest rates of use (83%). Estimates of contraceptive prevalence in 2000 were 78% for developed nations, 65% in developing countries, and32% in least developed nations.

Nine of ten contraceptive users reported using a modern contraceptive method. Female sterilization, IUD, and oral contraceptives account for two-thirds of use worldwide. Female sterilization was the most prevalent method (almost 33%). When considering only modern methods of contraception – such as hormonal contraceptives, an IUD, or female sterilization – the prevalence of contraceptive use was 58% in developed and 52% in developing nations, respectively.

Modern methods account for a larger share of use in developing nations (90%) than in developed nations (70%). Traditional methods like withdrawal and the rhythm methods are used more commonly in developed nations. These methods account for 26% of total use in developed regions compared with 8% in less developed areas. The most common method of contraceptive used in developed nations was condom, whereas in developing nations female sterilization was the most common contraceptive method reported.

Globally the demand for contraceptives exceeds access. Social and religious conventions may interfere with women’s ability to use contraceptives, often forcing women into clandestine use of contraceptives or abortion.

Abortion

Approximately 26 million legal and 20 million illegal abortions were performed worldwide in 1995. This number correlates with a rate of 35 per 1000 women or approximately one in four of all pregnancies (Henshaw et al., 1999). Illegal abortions are of particular concern because they may be unsafe. Illegal abortions are more likely to be performed by untrained providers, use hazardous techniques, and/or occur in unsanitary conditions. A WHO report estimated that 19 million of the abortions performed each year are unsafe. That is, there is one unsafe abortion performed for every six live births, although this varies by region: there is 1 unsafe abortion for every 3 live births in Latin America, in contrast to 1 for 25 in developed countries. The WHO estimates that almost all unsafe abortions take place in the developing world – only 500 000 of 19 million unsafe abortions (2.6%) performed each year are in developed countries. Nine percent of abortions in developed nations are performed illegally in stark contrast with 54% in developing nations (Henshaw et al., 1999).

Among the 19 million women receiving unsafe abortions each year, approximately 68 000 women die following the procedure. Like the distribution of unsafe abortions, the majority of deaths are in developing countries. Of the 68 000 women who die each year from unsafe abortion, only 300 were from developed nations. In developing countries, one mother dies for every 270 unsafe abortions performed. Unsafe abortion is a significant contributor to the total number of maternal deaths in some nations. Abortion-related mortality was highest in Latin American and the Caribbean and remained an important contributor to overall mortality in Eastern Europe and parts of Africa.

Young women are more likely to receive an unsafe abortion. Adolescents often wait longer before receiving an abortion, are less able to locate skilled care, are more likely to use dangerous methods, and take longer to receive care for complications.

Pregnancy

Health Care During Pregnancy And Delivery

Worldwide, approximately 72% of women receive some health care during pregnancy, although the availability and receipt of antenatal care vary by income and urbanization. In developed nations almost all women – 98% – receive some antenatal care. In contrast in developing nations, only two-thirds receive antenatal care. The region of the world with the lowest levels of reported antenatal care is in south Asia, where just over half of women receive antenatal care during pregnancy. In Nepal and Pakistan only one in four women receive antenatal care. According to estimates published by AbouZahr and Wardlaw (2003) for UNICEF, levels of antenatal care improved considerably between 1990 and 2000. The percentage of women receiving antenatal care in developing countries rose from 53 to 64%, an increase of 21%. The largest percent increase was observed in Asia (from 45% to 59% – an increase of 31%).

Although considerable effort has been expended to improve access to antenatal care, based on the belief that early detection of particular risk factors will reduce morbidity or mortality, more recent efforts have shifted to emphasize quality health care during delivery. Healthcare access during delivery also varies considerably by region. Data made available by UNICEF show that between 1995 and 2003 most women in industrialized nations had a skilled attendant present at delivery (99%), whereas only 59% in developing nations and 32% in the least developed nations had a skilled attendant. The percentage of women with a skilled attendant increased significantly between 1990 and 2003 for many developing nations. The exception was sub-Saharan Africa, which had only a 3% increase. Moreover, access to some healthcare services does not guarantee access to needed services. For example, a recent study of maternal deaths in Ghanaian hospital found that one-third of women in need of a cesarean section were able to receive one (Baiden et al., 2006).

Maternal Mortality

It is estimated that more than a half-million women die each year due to maternal mortality. Of these deaths 99% occur in developing nations. Sources of maternal mortality include both direct – deaths due to obstetric complications (pregnancy, labor, or puerperium), interventions, omissions, or incorrect treatment – and indirect obstetric deaths – deaths resulting from previous disease or disease developed during pregnancy that was aggravated by the pregnancy.

Women living in developed regions of the world have a 1 in 2800 lifetime risk of maternal death. In contrast, women in the developing world have a 1 in 61 lifetime risk of maternal death (Haub, 2005) Maternal deaths vary by cause globally. Hemorrhage was the leading cause of maternal death in Africa and Asia, whereas hypertensive disorders represent the highest cause of death in Latin America and the Caribbean. Maternal mortality is highest in developing regions. The lifetime risk of maternal death is:

- 1 in 20 in Africa (1 in 16 in sub-Saharan region)

- 1 in 83 in Oceania (Pacific Islands)

- 1 in 93 in Asia

- 1 in 160 in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Individual countries with the highest maternal mortality ratios (maternal deaths per 100 000 live births) are:

- Sierra Leone

- Afghanistan

- Malawi

- Angola

Higher rates of maternal mortality are associated with urbanization, poverty, and young maternal age. These factors also affect the distribution of maternal mortality in developed nations. For example, in the United States black women have maternal mortality rates three to four times that of white women.

Multiple studies have found that the majority of maternal deaths in developing nations are avoidable; that is, those deaths could have been prevented if feasible actions had been taken. Improvements in the quality of healthcare providers, availability of health-care facilities and resources, and access to health care could substantially reduce avoidable maternal mortality. A study of Palestinian women in the West Bank found that access to lifesaving care was often delayed due to mobility and security concerns (Al-Adili et al., 2006).

Avoidable deaths are not only a problem in developing nations. A study conducted in the United States found that 40% of maternal deaths in one state were avoidable (Berg et al., 2005). The causes of avoidable deaths were the same as those observed in developing nations – substandard medical care or facilities, inaccessibility of health care, and iatrogenic illness (e.g., infections or complications).

Worldwide efforts to decrease the rates of maternal mortality have been underway with little overall improvement, although interventions to reduce maternal mortality can be successful under certain conditions. A multipronged initiative implemented in Egypt that focused on provider training and education, community awareness, and improved health facilities halved the maternal mortality rate between 1992 and 2000 (Campbell et al., 2005).

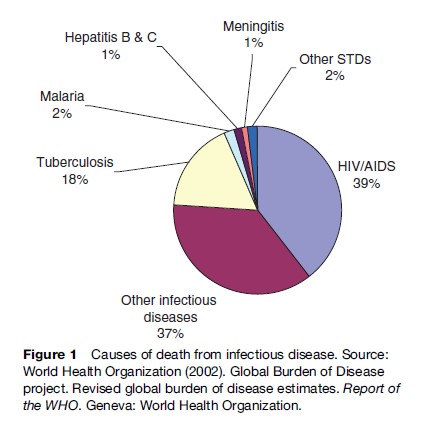

The Role Of Infectious Disease in Women’s Health

Infectious disease is the second leading cause of death among women, killing almost 2.5 million women each year (see Figure 1). One of every five deaths among women is due to an infectious disease. Infectious diseases are often associated with poverty. Such factors as poor living conditions, inadequate health care, and lack of sexual autonomy put women at increased risk of infection.

Tuberculosis

Approximately one-third of the world’s population is infected with tuberculosis (TB). TB was responsible for2% of deaths among women and for 18% of deaths in women due to infectious disease in 2002. Annually, there are 2.7 million new infections in women and 550 000 deaths. Many studies have shown that twice as many men as women die from TB each year. However, a prevalence study conducted in Vietnam found that men and women were similarly affected by tuberculosis (Thorson et al., 2004). This finding raises the question whether women have a similar prevalence of TB as men, but those cases are undetected or undiagnosed. The debate is ongoing over when this discrepancy is related to biological or social factors. The Vietnamese study found that case detection for both sexes was poor, but was worse among women (39% for men vs. 12% for women; Thorson et al., 2004). Poor case detection for women may occur because fewer women present for treatment, fewer receive testing, and fewer test positive. A common test for TB, sputum microscopy, appears to be less sensitive in women. Similarly, among those diagnosed with TB, there is a longer delay in the appearance of symptoms in women compared to men (Long et al., 1999); this difference is believed to be due in part to differing symptom presentations. Women less often report certain key symptoms, such as cough or sputum expectoration, which are associated with faster diagnosis. Whether reporting is influenced by the presence of less severe symptoms or an individual reluctance to report symptoms for fear of the potential stigma is not known but, regardless, will affect women’s access to treatment and TB-related morbidity.

TB affects predominantly individuals between the ages of 15 and 44 years of age, resulting in a significant impact on the families of TB patients through loss of income and reduced ability to provide caregiving. Pregnancy may significantly affect the progression of TB, but it is not yet clear whether this is a result of accelerated progression or an artefact of increased use of health care. Significant social stigma may accompany a diagnosis of TB, especially in regions where TB and HIV co-infection are common. Women are especially vulnerable to stigma and may delay or refuse to seek medical care as a result.

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease endemic to many tropical and subtropical countries. Malaria is the cause of only 2.4% of deaths in women globally, but is a significant source of disability. The WHO Global Burden of Disease Project has estimated that there were over 200 million incident cases of malaria in women in 2002 and almost 2 million years lost to disability.

Pregnancy is a period of increased risk for malaria. Pregnancy is believed to decrease immunity to one of the parasites responsible for malarial infection, Plasmodium falciparum. Malaria during pregnancy is associated with maternal anemia and multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes, which include low birth weight, preterm delivery, and intrauterine growth restriction. Preventive measures, like insecticide-treated bed nets and intermittent preventive treatment, have proven effective in reducing malaria, but are not systematically employed due to lack of knowledge about the interventions, lack of access, or lack of affordability. The rainy season, early gestational age, timing of the first prenatal health-care visit, and young maternal age have all been found to be associated with a higher prevalence of malarial infection.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

In 2002 there were an estimated 1.1 million deaths in women due to sexually transmitted diseases (STD). The overwhelming majority of deaths (96%) were due to HIV/ AIDS, but more than 50,000 deaths occurred as a result of syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, or some other sexually transmitted infection. Forty percent of HIV-related and 25% of non-HIV STD-related deaths occurred among women under the age of 30.

HIV/AIDS

HIV is a virus that targets cells of the immune system, progressively destroying the body’s ability to respond to infections and certain cancers. The prevalence of HIV infection in the general population ranges from a low of 0.2% in the Middle East/North Africa to a high of 7.2% in sub-Saharan Africa. There are an estimated 17.5 million HIV-infected women worldwide:

- 5 million in sub-Saharan Africa

- 0 million in Asia

- 580 000 in Latin America

- 490 000 in North America/Central and Western Europe

- 440 000 in Eastern Europe/Central Asia

- 220 000 in Middle East/North Africa

- 140 000 in the Caribbean

- 39 000 in Oceania.

Recent studies of the spread of HIV show variability by region. The prevalence of HIV in women increased between 2003 and 2005 in Oceania, North America/ Central America, Western Europe, and Eastern Europe/ Central Asia; decreased slightly (from 7.3 to 7.2%) in sub-Saharan Africa, and remained constant in the other regions.

HIV has had a disproportionate impact on the health and lives of women. Women may be more physiologically susceptible to HIV infection due to factors such as genital tract biology, hormonal contraceptive use, and the presence of sexually transmitted infections. Yet, many social factors also contribute to this disparity. The major burden of HIV is among women who are disadvantaged – those living in impoverished conditions, young women, and racial and ethnic minorities. In one South African survey females aged 15–24 years had infection rates three times that of similar-aged males (15.5 vs. 4.8%; Pettifor et al., 2005).

Studies of HIV transmission provide stark evidence of the direct impact of women’s position in society and its consequences on health. Age and economic differences between young women and their sexual partners are directly related to sexual practices, condom use, and violence. In addition to the direct impact of HIV, women are more often primary caregivers for HIV/AIDS patients. As such, they are more likely to spend time and effort in the caretaking of loved ones, negatively affecting their own jobs, income, or schooling.

The impact of HIV among women has become evident through dramatic shifts in the demographic characteristics of certain nations. For the first time, the life expectancy for women fell below that of men in four African nations with high HIV prevalence (Population Division, 2005). Globally, half of HIV infections are in women. In sub-Saharan Africa 57% of infections are in women.

Other Sexually Transmitted Infections

In 2002 there were an estimated 50 000 deaths and 4.5 million years lost to disability due to non-HIV sexually transmitted infections in women. Syphilis was the leading cause of death, but chlamydia and gonorrhea were the largest contributors to disability (see Table 2).

Syphilis, when untreated, can result in pregnancy loss, complications for newborns, and, in its later stages, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and nervous system disorders. In 1999 there were an estimated 5 million new cases of syphilis worldwide. Over half of new infections occurred in sub-Saharan Africa (1.7 million) and South and Southeast Asia (1.9 million) with an additional 1.3 million infections in Latin America and the Caribbean. Moreover, although the overall prevalence of syphilis in Western Europe is low, the states of the former Soviet Union have experienced sharp increases in syphilis rates since 1989.

Chlamydia is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium, Chlamydia trachomatis, that is a common cause of pelvic inflammatory disease and cause of infertility. Chlamydia is often a silent infection – as many as 70 to 75% of affected women may be asymptomatic – highlighting the importance of health-care access to screening and treatment. The prevalence of chlamydia varies globally and unlike many other health conditions is common in developed as well as developing nations. In 1999 there were an estimated 50 million new cases in women, 3 million of which were in the United States alone. Chlamydia disproportionately affects young women and disadvantaged women. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance data have shown that chlamydia disproportionately affects both young (2761.5 per 100 000 among those 15–19 years and 3630.6 for women 20–24 years) and black women (1722.3 cases per 100 000 vs. 226.6 for white women).

Gonorrhea is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium called Neisseria gonorrhoeae and is a common cause of infertility, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, and chronic pelvic pain. Like chlamydia, gonorrhea is often asymptomatic – approximately 80% of women report no symptoms. The prevalence of gonorrhea has been highly variable, decreasing dramatically in some regions, like the United States and Western Europe, while increasing in others. In 1999, there were almost 1 million new infections in women in the United States and over a half-million in Western Europe.

Screening and treatment are important tools in the reduction of the prevalence and consequences of syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea. The diagnosis of syphilis is simple and inexpensive, yet often unavailable in developing countries. The diagnosis of chlamydia and gonorrhea involves costly tests and sophisticated equipment – often making the identification of these curable infections prohibitive in resource-poor environments.

Other Significant Sources Of Morbidity

Female Genital Mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is the removal of part or all of the female genitalia. Procedures vary in severity from removal of the clitoral hood to infibulation, a procedure defined by Amnesty International as ‘clitoridectomy (where all, or part of, the clitoris is removed), excision (removal of all, or part of, the labia minora), and cutting of the labia majora to create raw surfaces, which are then stitched or held together in order to form a cover over the vagina when they heal.’ An estimated 100 to 120 million women have undergone FGM, and an additional 2 million are at risk each year. The prevalence of the practice varies widely. Studies in Nigeria found that approximately half of women studied had experienced FGM, with the frequency of occurrence positively correlated with age and negatively correlated with education. The age at which FGM occurs varies from birth to first pregnancy, but is most common in childhood – from 4 to 8 years in age.

FGM has both immediate and long-term health consequences. The immediate effects include severe pain, hemorrhage, infection, injury to surrounding tissue, and infection from unsanitary surgical instruments. Long-term impacts may be physical or psychological. Physical implications may include keloid scar formation, damage to the urethra, painful sexual intercourse or sexual dysfunction, or complications during childbirth. Psychological implications include posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression.

FGM is most commonly thought of as a practice occurring in African nations. However, although FGM does occur in 28 African nations, it is also a cultural practice in parts of Asia (among Muslim populations in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and India) and the Middle East (Egypt, Oman, Yemen, and the United Arab Emirates). Further, although not widespread, there are sporadic reports of practice of FGM among indigenous groups in Central and South America. FGM also occurs in developed nations, but predominantly among immigrant groups.

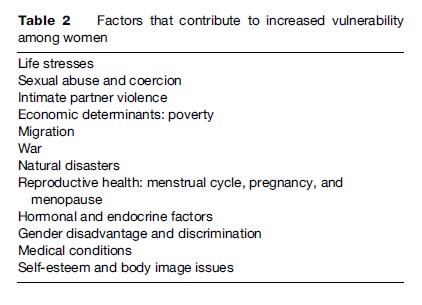

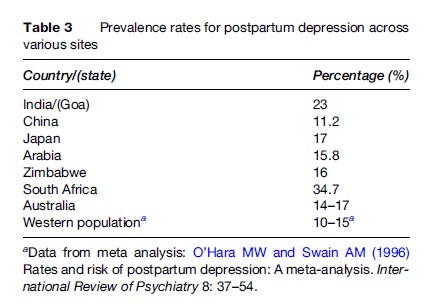

Mental Health

Many mental health conditions, most notably depression and anxiety, are more common among women than men (see Table 3). The disparity by gender exceeds differences in biology, and the relationship among poverty, social position, and these illnesses has been well documented. Women living in situations of deprivation often lack access to psychiatric health care and facilities and are often at increased vulnerability to potential social and economic consequences related to stigma.

According to the WHO, as many as one-third of all nations have no formal mental health system. Although mental health-care interventions and treatment regimens have proven effective in developing countries, they have not been implemented widely. As few as 10% of affected individuals living in developing nations may have access to any psychiatric care.

Global surveillance data on mental health issues are sparse. The Global Burden of Disease Project of the World Health Organization has estimated a prevalence of 200 million women with psychiatric illness in 2002. Table 3 shows an estimated 95 million women had unipolar depressive disorder and 19 million had panic disorder. Moreover, almost 17 million had posttraumatic stress disorder, a condition that occurs as the result of past traumatic experiences, such as violence or rape. These three conditions alone are associated with significant disability, accounting for over 44 million years lost to disability.

Violence

Violence is a significant contributor to women’s mortality and morbidity. In 2002 more than 100 000 women died as a result of violence and war, and there were almost 1 million years lost due to disability following violence. Violence against women may take many forms. It may be experienced within an intimate relationship in the form of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse by a partner or family member. It may be within a community in the form of physical or sexual abuse by a neighbor or stranger. Finally, it may be experienced within a society in the form of systematic violence against women, as has been documented during recent violent conflicts in Sudan and Liberia.

Violence in domestic relationships is common in the developed and developing world. Ramiro examined severe psychological violence in four developing nations and found that lifetime prevalence ranged from a low of 10.5% in Egypt to a high of 50.7% in Chile. A met analysis of intimate partner violence in developing countries found high rates of lifetime experiences of violence – from 18 to 57% – and high rates of violence during pregnancy from 4 to 28% (Nasir and Hyder, 2003).

Violence affects women’s health in many ways. There are the immediate impacts of violence against women, such as injury and death, as well as long-term consequences. The long-term impact of violence against women includes unintended pregnancy, maternal death, sexually transmitted infections, as well as mental health problems including posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and substance abuse.

Conclusion

When women are living without autonomy their health is at risk. Lack of autonomy may result in increased vulnerability to a host of medical concerns – from interpersonal violence, to unintended pregnancy or sexually transmitted infection, to the inability to receive health care or medication for curable conditions. Lack of access to health care or information, lack of control over one’s body, and economic or social vulnerability when ill all have the potential to affect women’s health. Although the economic and medical infrastructure are vastly different in developing and developed nations, the conditions that contribute to women’s vulnerability are universal. Poverty; social conventions regarding gender roles that limit women’s access to opportunities, information, and resources; and the effects of inequities in the home, community, and society all work in concert to increase vulnerability and deleteriously affect women’s health.

Bibliography:

- AbouZahr C and Wardlaw T (2003) Antenatal Care in Developing Countries: Promises, Achievements and Missed Opportunities. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization and UNICEF.

- Al-Adili N, Johansson A, and Bergstrom S (2006) Maternal mortality among Palestinian women in the West Bank. International Journal of Gynaecology Obstetrics 93: 164–170.

- Baiden F, Amponsa-Achiano K, Oouro AR, et al. (2006) Unmet need for essential obstetric services in a rural district in northern Ghana: Complications of unsafe abortions remain a major cause of mortality. Public Health 120: 421–426.

- Berg CJ, Harper MA, Atkinson SM, et al. (2005) Preventability of pregnancy-related deaths: Results of a state-wide review. Obstetrics and Gynecology 106: 1228–1234.

- Brands A and Yach D (2002) Women and the Rapid Rise of Noncommunicable Disease. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Campbell O, Gipson R, Issa AH, et al. (2005) National maternal mortality ratio in Egypt halved between 1992–93 and 2000. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 83: 462–471.

- Fuentes R, Ilmaniemi N, Laurikainen E, et al. (2000) Hypertension in developing economies: A review of population-based studies carried out from 1980 to 1998. Journal of Hypertension 18: 521–529.

- Haub C (2005) 2005 World Population Data Sheet. Washington, DC: Population Research Bureau.

- Henshaw SK, Singh S, and Hass T (1999) The incidence of abortion worldwide. International Family Planning Perspectives 25: S30–S38.

- Husten L (1998) Global epidemic of cardiovascular disease predicted. Lancet 352: 1530.

- Long NH, Johansson E, Lonnroth K, et al. (1999) Longer delays in tuberculosis diagnosis among women in Vietnam. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 3: 388–393.

- Mathers CD, Bernard C, Iburg KM, et al. (2003) Global Burden of Disease in 2002: Data Sources, Methods and Results Global Programme for Health Policy Discussion Paper No. 54. World Health Organization, revised 2004.

- Nasir K and Hyder AA (2003) Violence against pregnant women in developing countries: review of evidence. European Journal of Public Health 13: 105–107.

- Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, et al. (2005) Young people’s sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS 19: 1525–1534.

- Population Division (2005) World population prospects: The 2004 revision. Highlights. Report of the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. New York: United Nations.

- Raymond SU, Greenberg HM, and Leeder SR (2005) Beyond reproduction: Women’s health in today’s developing world. International Journal of Epidemiology 34: 1144–1148.

- Thorson A, Hoa NP, Long NH, et al. (2004) Do women with tuberculosis have a lower likelihood of getting diagnosed? Prevalence and case detection of sputum smear positive pulmonary TB: A population-based study from Vietnam. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 57: 398–402.

- World Health Organization (2002) Global Burden of Disease project. Revised global burden of disease estimates. Report of the WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, and Anand S (2001) Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Part I: General considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation 104: 2746–2753.

- AbouZahr C and Wardlaw T (2001) Maternal mortality at the end of a decade: Signs of progress? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 79: 561–568.

- Ahman E and Shah I (2004) Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2000, 4th edn. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Goldman MB and Hatch MC (eds.) (2000) Women and Health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, and VanLook PF (2006) WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: A systematic review. Lancet 367: 1066–1074.

- Miller G (2006) Mental health in developing countries. The unseen: Mental illness’s global toll. Science 311: 458–461.

- United Nations (1998) Levels and trends of contraceptive use as assessed in 1998. Report of the UN Department for Economic and Social Information and Policy Analysis. Population Division. New York: United Nations.

- UNAIDS (2005) AIDS epidemic update: December 2005. Report of the Joint UN Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2001) Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections: Overview and estimates. Report of the WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.