Sample Compression Of Morbidity Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The compression of morbidity paradigm (Fries 1980) envisions reduction in cumulative lifetime morbidity principally through primary prevention, by postponing the age of onset of morbidity to a greater amount than life expectancy is increased, largely by reducing the health risks which cause subsequent morbidity and disability. Recent data document slowly improving age-specific health status for seniors, indicate that postponement of the onset of disability by at least 10 years is feasible, and prove the effectiveness of some specific lifestyle modification interventions by randomized controlled trials.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The health of senior persons is the largest of all health problems in the developed nations. Over 80 percent of all illness, morbidity, mortality, and medical costs are concentrated in the years after age 65. The illness burden is mostly made up of chronic illness, complicated by the frailty of increasing age. In the twentieth century we saw a transfer of the illness burden from the acute infectious diseases prevalent in 1900 to ascendancy of chronic disease by mid-century, to a decline in major chronic illnesses, led by cardiovascular disease, and now to the slow transition from chronic disease per se to the associated problems of aging (Fries 1980).

1. An Overview Of The Aging Process

1.1 Mortality Changes Over Time

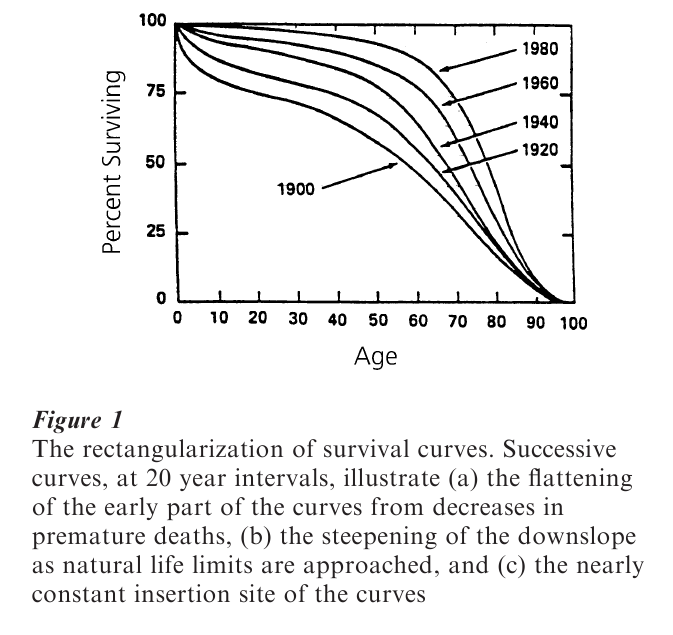

Changes in survival curves in developed nations over the twentieth century are instructive, since they lead us beyond a simplistic, if popular, notion of ever-increasing life expectancy. Life expectancy from birth is affected most strongly by changes in infant mortality rates and in deaths in early and middle life. Successive survival curves (Fig. 1) have become more rectangular, as marked reduction in deaths at early ages flatten the initial part of the curve. There are now few deaths prior to age 50 or 60. At the same time, the downslope of the curves has become steeper, and the insertion point has changed little (Fries and Crapo 1981). A natural barrier to biologic longevity may be visualized through these successive curves. In the USA, life expectancy from birth increased from 47 to 76 years in the twentieth century. However, life expectancy from advanced ages has changed relatively little. From 1980 to 1998, life expectancy for females from age 65 increased only by 0.7 years in contrast to more rapid rises in prior decades. Life expectancy for both sexes from age 85 remained stable at 6.1 to 6.3 years in the USA in the 18 years from 1981 (Kranczer 1999). Projections for future increases vary widely from high (Manton et al. 1991) to low (Olshansky et al. 1990). Nevertheless, with increasing size of successive birth cohorts and with increased survival to age 65 or age 85 the absolute numbers of senior citizens will increase very substantially in coming years.

1.2 Declines In Organ Reserve Function With Age

Data from longitudinal studies of aging show a consistent decline in the maximum function of the various organs with age, the decline being essentially linear at a rate of 1.5 percent per year after age 30. Data on maximal performance, such as world record marathon times, similarly show a nearly linear decline with age at the same rate (Fries and Crapo 1981).

Physiologic normal values, however, remain constant with increasing age. Normal pH, blood chemistry, white count, and other homeostatic values do not vary over the lifespan, representing the internal physiologic environment essential for cellular function. However, with the linear decrease in organ reserve in multiple organs, the ability to respond physiologically to a perturbation decreases exponentially. As a result, mortality rates increase exponentially, with a doubling of mortality rates each seven or eight years after age 30 (Fries and Crapo 1981).

With these realities of human aging comes a paradox: the decline in organ reserve is inevitable, yet organ reserve can be increased quite readily, at almost any age (Rowe 1999). For example, an increase in exercise levels can increase cardiopulmonary reserve very substantially, even at advanced ages (Stewart et al. 1993, Fries et al. 1996).

1.3 Enhanced Personal Autonomy And Modifiable Determinism

In philosophic writings, a classical conflict has been between the advocates of free will and those of determinism, and this conflict now exists in modern dress. Determinism is represented by molecular genetics, with the sometime notion that your health over the lifespan is ultimately determined only ‘by your genes.’ Free will is represented by the advocates of health promotion, seeking voluntary changes in behavioral risk factors, such as lack of exercise, cigarette smoking, obesity, and excessive dietary fat; changes which can enhance organ reserve, preserve function, and extend life. In this view, health requires that you ‘take care of yourself.’ The tension between these two paradigms is complex and sometimes un-easy.

2. The Compression Of Morbidity

2.1 The Hypothesis And The Paradigm

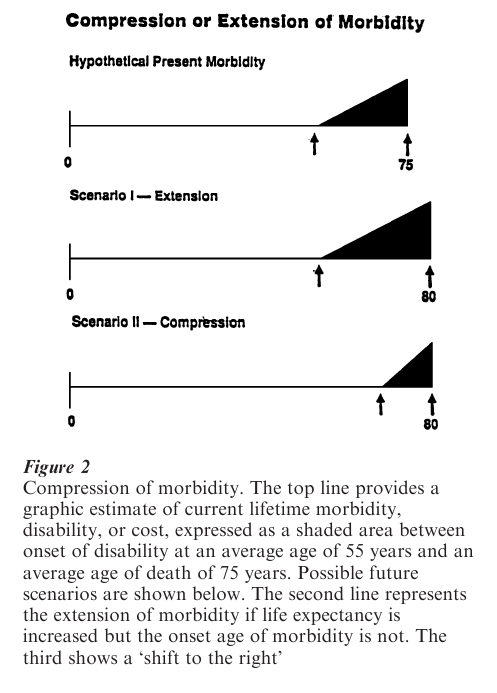

The compression of morbidity hypothesis was introduced in 1980 (Fries 1980) and has become a major paradigm underlying health improvement programs and health improvement policies directed at more successful aging (Fries et al. 1998). Most morbidity results from chronic processes of disease and frailty and is concentrated in the years prior to death. The goal is compression of morbidity between its time of onset, currently averaging 55 years, and the age of death, currently averaging 76 years, as diagrammed in Fig. 2. A crescendo of increasing morbidity occurs, on average, over this period.

With social and scientific progress it is likely that both the age of onset of infirmity and the age at death will increase over time. At issue is the relative movement of the two points. If mortality decreases predominate there may be more morbidity in the typical life, the so-called ‘failure of success’ (Gruenberg 1977, Verbrugge 1984, Scheider and Brody 1983), as shown in the second line of the figure. If postponement of the age of onset of morbidity predominates, then morbidity is compressed and the average illness burden is less, the period of adult vigor is prolonged, life quality is improved, and the need for medical care and associated costs may be reduced.

For many, the ideal life is one vigorous and vital over the lifespan, with a terminal collapse of physical and mental function limited to a few months or years immediately preceding death (Fries and Crapo 1981). A central issue, when considering the eventual impact of new scientific discoveries or behavioral changes, is whether they may add years of health or add years of illness to the average life. If morbidity is compressed by a new advance then the advantage is clear; if the process of dying is prolonged then major ethical issues arise (Verbrugge 1984).

2.2 Trends In Morbidity Compression

Since the early 1980s there has been some compression of morbidity in the elderly, as documented by a number of recent studies (Manton et al. 1997, Nusselder and Mackenbach 1996, Allaire et al. 1999). The major chronic illnesses, including heart disease, cancer, and stroke, are about 70 percent preventable. The true causes of death are not the chronic diseases themselves but the underlying causes of these diseases, which are led by cigarette smoking, sedentary living, obesity, and diets high in saturated fat and low in complex carbohydrates (McGinnis and Foege 1993). The potential for postponement of morbidity is now much better understood.

Freedman and Martin (1998), among others, have shown significant age-specific functional improvement in seniors over a recent seven-year period. Cross-sectional studies have suggested compression of morbidity in favored groups, such as those with higher levels of education (Leigh and Fries 1994), higher socioeconomic status (House et al. 1990), and those with fewer lifestyle health risks (Vita et al. 1998). Daviglus and colleagues (1998) showed substantial decreases in Medicare costs for those with few health risk factors in midlife. Reed and colleagues (1998) related healthy aging to prospectively determined health risks. Allaire et al. (1999) showed a reduction of disability of 25 percent across successive generations in the Framingham study. Clearly, social and behavioral health risks make a very major contribution to both morbidity and mortality. Selected medical advances also evidently contribute to compression of morbidity, from established therapies such as total joint replacement and cataract extraction to any other treatment which makes a major contribution to life quality. The central measure of success at compression of morbidity is reduction in average cumulative lifetime morbidity (Vita et al. 1998, Wang et al. 1999, Hazzard 1997). Hitt et al. (1999) analyzed morbidity in centenarians and found it to be mild, with a rapid terminal decline.

3. How Long May The Onset Of Morbidity Be Postponed?

Substantial numbers of aging seniors in two cohorts have been followed longitudinally to identify the factors which postpone onset of morbidity, the magnitude of the postponement, and the effects of lifestyle health risks, using disability as a definable and measurable surrogate for morbidity and cumulative disability as a surrogate for cumulative lifetime dis-ability.

The University of Pennsylvania Study followed 1,741 university attendees studied in 1939 and 1940, surveyed again in 1962, and followed annually since 1986. Health risk strata were developed for persons at high, moderate, or low risk, based upon cigarette smoking, body mass index, and lack of exercise, and assigned by risk status in 1962 (average age 43 years). Persons with high health risks in 1962 or in 1986 had twice the cumulative disability of those in the low risk strata. This 100 percent decrease in disability rates was offset only partially by a 50 percent decrease in mortality rates in the high risk strata, documenting compression of morbidity. Onset of disability was postponed by about seven years in the low risk stratum as compared with the high stratum (Vita et al. 1998).

In the Precursors of Arthritis Study 537 senior runners and vigorous exercisers and 423 age-matched community controls were studied over 13 years with careful controls for self-selection bias. The exercising group has had less than one-half the cumulative disability of the sedentary controls and differences between groups has actually increased over time. The proportion of those disabled was also reduced by more than one-half in the exercise groups. The postponement of disability for the exercising group was 8.7 years for minimum disability and approximately 12 years for higher levels of disability (Wang et al. 1999).

While these two studies are the only ones to directly assess the magnitude of morbidity progression they are entirely consistent with the larger literature (Stewart et al. 1993, Daviglus et al. 1998, Freedman and Martin 1998, Campion 1998, Allaire et al. 1999, Reed et al. 1998).

4. Randomized Controlled Trials Of Behavioral Interventions

Epidemiologic studies of associations, no matter how strong and consistent, ultimately require randomized study of interventions for proof of causality, and a number of these are now available (Fries et al. 1998). Health promotion programs in senior populations directed at risk prevention, health improvement, and medical cost reduction have been studied in a number of large and well-performed randomized trials, with positive results. The Bank of America randomized study of 4,500 retired subjects reduced risks by 12 percent in the intervention groups in the first year compared with controls and reduced medical care requirements by even more, confirmed by study of medical claims (Fries et al. 1993). The California Public Employment Retirement System study (Fries et al. 1994), involved 57,000 subjects in a one-year randomized trial with similarly dramatic results con-firmed by claims data endpoints. Over 42 carefully designed high quality health improvement programs have now been proven effective and cost-effective at preventing illness and at reducing medical need (Fries et al. 1998).

5. Issues For Contemplation

The human aging process, when not prematurely stopped by trauma or disease, moves toward multiple organ system frailty (Fries et al. 1998). The immediate cause of death shifts from external toward intrinsic factors. The formally assigned ‘cause of death’ becomes increasingly irrelevant compared with the underlying frailty, the inability of the aging organism to withstand even a minor perturbation. With frailty, an analogy is an old curtain, rotted by the sun, where an attempt to repair a tear in one place is followed by a tear in another.

William Osler considered pneumonia to be the ‘old mans’ friend,’ terminating the infirmities of frailty. Influenza epidemics result in an increase in death rates, but they are followed by a six-month period of death rates which are actually below expected baselines. Pneumovax and influenza vaccines can prevent a number of specific perturbations and associated attributable deaths, but only in the context of multiorgan frailty. The ultimate health benefits of successful interventions in the terminally frail may prove in substantial part illusory when so many competing risks remain.

Health policies directed at healthy aging may now be visualized quite clearly. An underlying paradigm is the compression of morbidity. Prospective longitudinal studies now link health outcomes firmly with antecedent health risk factors, providing proof of concept. Randomized controlled trials of interventions in seniors document the ability to reduce health risks, to improve outcomes, and to reduce costs, providing proof of causality. National and inter-national initiatives are now needed to provide these benefits to populations.

Bibliography:

- Allaire S H, LaValley M P, Evans S R, O’Connor G T, Kelly-Hayes M, Meenan R F, Levy D, Felson D T 1999 Evidence for decline in disability and improved health among persons aged 55 to 70 years: The Framingham Heart Study. American Journal of Public Health 89: 1678–83

- Campion E W 1998 Aging better. New England Journal of Medicine 338: 1064–6

- Daviglus M L, Liu K A, Greenland P et al. 1998 Benefit of a favorable cardiovascular risk-factor profile in middle age with respect to medicare costs. New England Journal of Medicine 339(16): 1122–29

- Freedman V A, Martin L G 1998 Understanding trends in functional limitations among older Americans. American Journal of Public Health 88(10): 1457–62

- Fries J F 1980 Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. New England Journal of Medicine 303: 130–5

- Fries J F 1993 Compression of morbidity 1993: Life span, disability, and health care costs. Facts and Research in Gerontology 17: 183–90

- Fries J F, Bloch D A, Harrington H, Richardson N, Beck R 1993 Two-year results of a randomized controlled trial of a health promotion program in a retiree population: The Bank of America Study. American Journal of Medicine 94: 455–62

- Fries J F, Crapo L M 1981 Vitality and Aging. W. H. Freeman, San Francisco

- Fries J F, Harrington H, Edward R, Kent L A, Richardson N 1994 Randomized controlled trial of cost reductions from a health education program: The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (PERS) Study. American Journal of Health Promotion 8: 216–23

- Fries J F, Singh G, Morfeld D, O’Driscoll P, Hubert H 1996 Relationship of running to musculoskeletal pain with age: A six-year longitudinal study. Arthritis and Rheumatism 39: 64–72

- Fries J F, Koop C E, Sokolov J, Beadle C E, Wright D 1998 Beyond health promotion: Reducing need and demand for medical care. Health Affairs 17(2): 70–84

- Gruenberg E M 1977 The failures of success. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 55: 3–34

- Hazzard W R 1997 Ways to make ‘usual’ and ‘successful’ aging synonymous: Preventive gerontology. Western Journal of Medicine 167: 206–15

- Hitt R, Young-Xu, Silver M, Peris T 1999 Centenarians: The older you get, the healthier you have been. Lancet 354(9179): 452

- House J S, Kessler R C, Herzog A R et al. 1990 Age, socio-economic status, and health. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 68: 383–411

- Kranczer S 1999 US life expectancy. Statistical Bulletin Oct–Dec: 20–27

- Leigh J P, Fries J F 1994 Education, gender and the compression of morbidity. International Journal of Aging & Human Development 39: 233–46

- Manton K G, Stallard E, Tolley H D 1991 Limits to human life expectancy: Evidence, prospects, and implications. Population and Development Review 17: 603–37

- Manton K G, Corder L, Stallard E 1997 Chronic disability trends in elderly United States populations: 1982–1994.

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 94: 2593–98

- Mcginnis J F, Foege W H 1993 Actual causes of death in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association 270(19): 2207–12

- Nusselder W J, Mackenbach J P 1996 Rectangularization of the survival curve in the Netherlands, 1950–1992. Gerontologist 36: 773–82

- Olshansky S J, Carnes B A, Cassel C 1990 In search of Methuselah: Estimating the upper limits to human longevity. Science 250: 634–40

- Reed D M, Foley D J, White L R et al. 1998 Predictors of healthy aging in men with high life expectancies. American Journal of Public Health 88(10): 1463–8

- Rowe J W 1999 Geriatrics, prevention, and the remodeling of G medicare. New England Journal of Medicine 340: 720–21

- Scheider E L, Brody J A 1983 Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity: Another view. New England Journal of Medicine 309: 854–6

- Stewart A L, King A C, Haskell W L 1993 Endurance exercise and health-related quality of life in 50–65 year-old adults. Gerontologist 33: 782–9

- Verbrugge L M 1984 Longer life but worsening health? Trends in health and mortality of middle-aged and older persons. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 62: 475–519

- Vita A J, Terry R B, Hubert H B et al. 1998 Aging, health risks, and cumulative disability. New England Journal of Medicine 338: 1035–41

- Wang B W E, Ramey D R, Fries J F 1999 Postponed development of disability in senior runners: A controlled 13-year longitudinal study. Arthritis and Rheumatism 42(9): S74