View sample indigenous health research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a health research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The Health Of Indigenous Peoples

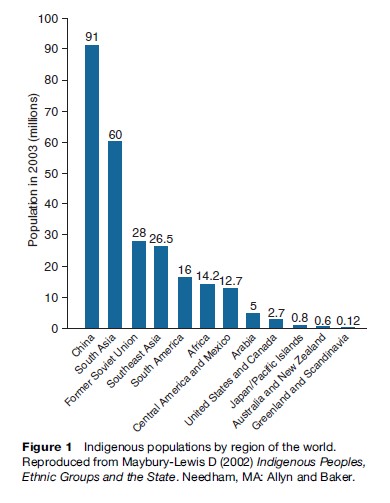

It has been estimated that there are approximately 300–500 million Indigenous peoples across the globe, belonging to 5000 distinct groups in more than 70 countries on every inhabited continent (Figure 1 provides one estimate of the global distribution of Indigenous populations). There has been increasing international attention given to the health and social circumstances of Indigenous peoples over the last couple of decades. Indigenous issues have been taken up by international bodies such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Labour Organization. This focus on Indigenous peoples is warranted considering the extent of health and social disadvantage that many Indigenous peoples experience. Nevertheless, there are ongoing debates about how the term Indigenous is defined.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Historically, it was those nation states that had formerly been European colonies that first recognized Indigenous peoples within their administrative and management systems. This process began in North America when those who were descended from the original inhabitants of the continent, the Native American, Canadian Aboriginal, Inuit, and Aleut peoples, were recognized as Indigenous. Western intergovernmental agencies, non-governmental organizations and academics further applied this way of thinking about Indigenous peoples beyond the Americas, with varying degrees of acceptance. In Australia and New Zealand, for instance, there was little debate about the existence of Indigenous minorities who had been dispossessed through colonization and subsequently incorporated into the political and administrative structures of a settler-dominated nation state. In Asia, governments such as Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Taiwan acknowledged some peoples as Indigenous (Maybury-Lewis, 2002). Similarly, the governments of Finland, Norway, and Sweden have recognized Indigenous populations. Elsewhere, however, the acknowledgement of Indigenous peoples has been more complicated. Prior to its collapse, the Soviet Union denied the existence of Indigenous peoples within its borders. China and India have sought definitions that would differentiate between populations they refer to as tribals or minority nationalities and Indigenous peoples (Bourne, 2003;Coates, 2004).

Ethnicity, Political Circumstance, Or History?

Today, people who describe themselves as Indigenous (or are described as such by others) are found around the world in widely varying social, cultural, political, and geographical contexts. However, there is no single definition that satisfactorily embraces the full range of this diversity. Since inclusion or exclusion from any definition can involve legal, social, and political rights, the debate is one which has generated considerable passion. As examples, the Yanomami of the Amazon River basin, living in a traditional way on traditional lands, would seem to meet every criterion of Indigenous peoples. This is also the case for the !Kung of Botswana, who live a mobile lifestyle in the Kalahari desert. But can the dominant population of Mongolia, which is also rooted in a mobile, pastoral lifestyle, also be considered Indigenous? The present-day descendants of once large and complex societies, such as the Mayan and Inca peoples of Central and South America, also identify themselves as Indigenous. What of those who occupy a position of power, such as the Kashmiri Pundits and white Afrikaners, both of whom have presented themselves to international organizations as Indigenous? What of those Indigenous peoples who no longer live in discrete remote communities but in large urban areas where they lead lives that on the surface seem very different from the traditions of their ancestors? These questions illustrate the dimensions of this debate.

Equally important – Who decides? How do you balance the rights of people to represent themselves with the interests of governments, academics, and international bodies who are also entangled in this definitional process? The efforts of organizations such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Labour Organization that have engaged with this problem demonstrate some of the difficulties in balancing such issues as self-identification, ascribed ethnicity, cultural characteristics, intercultural (and political) relationships, geographic location, and historical change in forming a definition of Indigenous peoples.

In 1972 a United Nations study developed a working definition that stated that ‘‘Indigenous communities, peoples and nations are those which, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those territories, or parts of them .. .’’ (cited in Coates, 2004: 6).

The International Labour Organization convention in 1989 defined Indigenous peoples as those ‘‘in independent countries who are regarded as Indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country … at the time of conquest or colonisation … and who retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions.’’ The debates about the definition of Indigenous peoples are not resolved. Nevertheless, it is possible to draw out of these discussions some of the characteristics that have been ascribed to Indigenous peoples (acknowledging the unresolved contradictions that reflect the tensions in thinking). Variously, Indigenous peoples have been described as people who:

- Lack political power and autonomy. Indigenous peoples are commonly political minorities in nation states dominated by settler societies or other ethnic majorities. Their contemporary political circumstance has been historically shaped by colonization in which Indigenous peoples have been dispossessed from their traditional lands and natural resources and subsequently incorporated within the institutional and political structures of the settler state. The management of Indigenous peoples by the settler state has often involved the development of administrative structures and programs. The rights of Indigenous peoples and those of the settler majority are frequently differentiated. This pattern of political disempowerment is reflected in other forms of social and cultural marginalization.

- Have relatively small populations and live in small-scale societies. While some populations, such as in China, are small relative to the dominant population, they are not necessarily small in absolute terms. Some Indigenous peoples, despite a history of colonization, now constitute a relative majority of the current population. It is also worth noting that many Indigenous peoples now live in urban communities.

- Have social identities that are derived from historical and lived connections to traditional territories and cultural practices. Notwithstanding, Indigenous identities are also complexly engaged with the realities of globalization and modernity.

- Were historically mobile peoples, whose movement over ancestral territories reflected their particular cultural and economic modes of production. However, some Indigenous peoples were historically tied to particular settlements which formed the center of their cultural and social life, and many Indigenous peoples today live more sedentary settled lives.

- May respond to social trends and cultural change in a way that is distinct from the dominant society. Some change may be resisted for a range of complex reasons, while Indigenous peoples may also embrace some forms of development.

- Have retained the desire to maintain a distinct identity and cultural practices in the face of a history of dispossession and social marginalization.

- Continue to maintain an understanding and sense of connection to a precolonial past, often passed on through oral testimony, ceremonies, and cultural activities, all of which serve to preserve the understanding of history.

- Are actively engaged in the decolonization and reindigenization processes – often participating in protests organized against colonial powers, global influences, environmental exploitation and the like – while seeking to maintain and protect their cultural independence despite economic pressure to adapt to a national or global mainstream.

Indigenous Health And Health Status

Measuring Indigenous Health And Indigenous Concepts Of Health

Although there has been an increase in international attention to the question of Indigenous health, information concerning their Indigenous health status is fragmented and incomplete. The quality of Indigenous health information varies according to the capacity, and willingness, of various nations to develop information systems that monitor Indigenous health outcomes. For example,

United States Associated Micronesia, where Indigenous peoples now constitute a majority of the population, lacks the capacity to support sophisticated health information systems (Anderson et al., 2006). Some nations do not systematically collect health data on Indigenous peoples. Even for those that do, data quality may be variable. In Australia, for example, quality mortality data are available for only 60% of the Indigenous population (Anderson et al., 2006). Indigenous data quality is shaped by a range of technical and social factors. Technical factors include the inclusion of data items on Indigenous status within administrative data sets and health surveys; definitions of Indigenous people; and the development of systems for the collation, analysis, and communication of Indigenous health information. Social factors include the willingness of institutions and people involved in the collection and collation of health information to commit to strategies to ensure high-quality data on Indigenous health. This may be particularly an issue in contexts in which Indigenous people are a relatively invisible minority.

The measurement of Indigenous health status tends to be framed by biomedically defined measures of health and illness. This may only partly capture different Indigenous understanding and conceptions of health. The 1999 Declaration on the Health and Survival of Indigenous Peoples by the World Health Organization proposed a definition of Indigenous health in which health

was both a collective and an individual inter-generational continuum encompassing a holistic perspective incorporating four distinct shared dimensions of life. These dimensions are the spiritual, the intellectual, physical, and emotional. Linking these four fundamental dimensions, health and survival manifests itself on multiple levels where the past, present, and future co-exist simultaneously. (World Health Organization, 2001)

While this definition points to the different dimensions of Indigenous understandings of health and well-being, it does not represent the complexity and diversity of all Indigenous world views. In order to meaningfully understand this, it is important to pay close attention to the particular cultural expressions of different Indigenous peoples. For example:

I think that well-being in our house and home and also with our neighbours is when there is peace and happiness – and also when we love ourselves. It’s like God says to us, you shouldn’t only want your own well-being, you should also think of your neighbours. You have to think of your neighbours, whether they have enough food to eat, or maybe they’re suffering. It is important to think of them. You have to share the happiness that you may have with your brother. (Juana Tzoy Quinillo, Santa Lucia la Reforma Municipality, Guatemala; Bristow et al., 2003)

Indigenous Health Inequalities

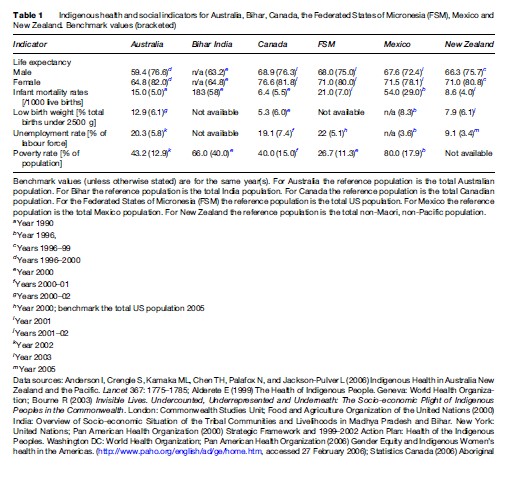

Indigenous peoples generally have much poorer health and social outcomes relative to non-Indigenous benchmarks. This is illustrated in Table 1, which compares Indigenous and non-Indigenous outcomes for Australia, Bihar (India), Canada, The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), Mexico, and New Zealand. The extent of disparity varies between Indigenous peoples, so generalizations can be problematic. However, Indigenous populations generally experience lower life expectancies; higher incidences of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancers; higher incidence of mental health disorders and substance misuse; and a relatively higher incidence of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and rheumatic fever (which are now uncommon among non-Indigenous people in most wealthy nations).

There are significant differences in life expectancy for Indigenous populations relative to non-Indigenous populations. For example, the life expectancy among the Maya of Guatemala is 17 years shorter than that for nonIndigenous peoples, while that of the Indigenous peoples of Mexico is more than 3 years shorter than the rest of the non-Indigenous population (Feiring, 2003). Disparities in life expectancies are also found in Australia, New Zealand, and Greenland. In Greenland, the life expectancy for an Inuit is not only shorter than that for a member of Danish non-Inuit communities, but also continues to be shorter than those in such developing countries as Brazil, China, and Thailand (Bristow et al., 2003; Stephens et al., 2005).

Indigenous health disparities are also reflected in differences in infant mortality rates. This is clear with respect to Australia, Bihar, and the Federated States of Micronesia, where the Indigenous infant mortality rate for each is three or more times that of non-Indigenous (see Table 1). The infant mortality rate among Indigenous peoples of Mexico is almost double that of non-Indigenous peoples (Pan American Health Organization, 2006).

The different patterns of mortality that are found in Indigenous populations have consequences in terms of the demographic structures of Indigenous populations, which have a relatively higher proportion of children and young adults compared with non-Indigenous populations. Thirty-three percent of Native Americans and nearly 50% of Indigenous peoples in Peru are younger than 15 years of age (Pan American Heath Organization, 2006).

The greater alienation and social-related stressors typically encountered by Indigenous peoples are also manifest in other health outcomes. For instance, 31% of First Nations people in Canada report some form of disability linked to high accident rates, poor housing, substance abuse, or chronic disease. Alaskan Natives report unintentional injury death rates more than three times the national average (Beavon and Cook, 2003). The suicide rate among Indigenous Hawaiians is more than 150% greater than that of non-Indigenous Hawaiians (Anderson et al., 2006).

Indigenous Health In A Historical And Social Context

There have been historical changes in the patterns of Indigenous health that arguably reflect the changing circumstance of colonial histories. From the beginnings of the European colonization of the Americas in the 1500s to the late 1900s, the absolute numbers of Indigenous populations declined precipitously. A range of factors were responsible, including the combined effects of infectious disease (such as smallpox, measles, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and influenza), economic devastation, frontier violence, forced relocation, and political and social marginalization. Notwithstanding the differences in these histories, there are significant commonalities in the health and social impacts of colonization with respect to Indigenous peoples such as Native Americans, the Indigenous peoples of Central and South America and the Caribbean, Australian Aborigines, native Hawaiians, the Saami of Norway, the Maori of New Zealand, and others (Kunitz, 1994; Coates, 2004).

During the twentieth century, Indigenous patterns of disease and illness began to reflect social changes such as urbanization and increasing exposure to commodity based lifestyles and their harms. This has been particularly evident with the rising incidence of chronic conditions such as end-stage renal disease, type 2 diabetes, and ischemic heart disease. At the same time, historical health problems associated with the consumption of drugs, such as alcohol and tobacco, have been overlain with the impact of other substances, and especially injecting drugs that are associated with blood-borne viruses such as HIV/AIDs and hepatitis B and C (Kunitz, 1994).

Disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations persist despite general improvements in health and standards of living among the latter. In fact, recent studies in the Russian Federation indicate that the socioeconomic and health status among the Indigenous peoples of the extreme northeast has deteriorated in recent years (World Health Organization, 2001). There is also some evidence that Indigenous health has improved over the last century (in places such as in Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Canada) despite continuing disparities.

Explanatory Frameworks For Indigenous Health Disparities

A number of explanatory frameworks have been used to account for disparities in Indigenous health, including racial difference, acculturation and risk behaviors, socioeconomic disadvantage, and the social processes associated with colonization.

Racial Differences

Racial difference, which assumes that Indigenous peoples have an underlying biological predisposition to poorer health status, is no longer a well-accepted basis for Indigenous disadvantage. Race theory proposed that Indigenous peoples were biologically predisposed to poorer health on the basis of their evolutionary poor fit within contemporary society. Race itself is generally now seen as a social construct emerging from colonial discourses rather than a valid scientific idea. However, the disrepute of race theory does not rule out a role of genetic factors in increasing the propensity to particular diseases in particular populations.

Health Behaviors

Other commentators have emphasized the development of risk behaviors (such as sedentary lifestyles, high-energy diets, smoking, and alcohol use) that have been associated with the adoption of Western lifestyles. This, it has been argued, is particularly pertinent for the development of chronic diseases such as diabetes or ischemic heart disease through behaviors associated with obesity, diet, and lack of physical activity. On a slightly different tack, it has also been argued that the process of cultural change (acculturation) has generated social stressors for Indigenous peoples that have also contributed to the development of a broad spectrum of illnesses.

Socioeconomic Disadvantage

Socioeconomic disadvantage is commonly seen to be a pertinent factor in shaping Indigenous health outcomes. The increased prevalence of poverty experienced by Indigenous peoples often involves more than marginal poverty – poor housing, low educational achievement, unemployment, and inadequate incomes – extending to profound poverty in which basic sustenance levels of food and shelter are compromised. There are also second and third-order implications of socioeconomic disadvantage. For instance, in the area of employment Indigenous peoples’ greater reliance on the informal labor market renders them more vulnerable to many work-related health hazards, while also excluding them from union and insurance benefits. Relatively poorer access to education compounds vulnerability in terms of both employment and poverty.

The morbidity and mortality profiles of Indigenous populations reflect those of the most underprivileged socioeconomic strata within the various nations. For example, in Peru the rate of poverty among Indigenous populations is 150% that of non-Indigenous populations. Ninety-one percent of Indigenous people in Guatemala lived in extreme poverty in 1989, compared to 45% of non-Indigenous. In Ecuador, 76% of Indigenous children live in poverty. Further, the tangible impact of such poverty is reflected in the figures found in Honduras where an estimated 95% of Indigenous children under the age of 14 are malnourished (Feiring, 2003). This is far from being only an American phenomenon, as shown by the fact that over half of the Tribal children in the Indian state of Bihar experience malnutrition (World Health Organization, 2001).

Historical Processes Of Colonization

Others have argued that Indigenous health outcomes have been shaped by historical processes of colonization. Colonization has impacted Indigenous health through a complex, multilayered process of social change. This includes the alienation of Indigenous peoples from their traditional resources through the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from traditional lands and the disruption of traditional lifestyles by the complex interplay of wars, frontier violence, environmental change, and population migration. Indigenous peoples have also been socially, economically, and politically marginalized within the developing settler society and its administrative and social systems. For instance, in Central and South America, many Indigenous communities lack access to clean water, adequate sewerage systems, electricity, and paved roads. There are many barriers to health-care access for Indigenous peoples, including remoteness, poverty, and cultural and linguistic differences. For example, one Indigenous woman of the Occopecca Community in Peru recounts:

After walking very slowly for about two hours with my husband, I arrived at the health centre. I was in pain and very frightened about using the service for the first time, but as other women told me it was more safe for me and the baby, my husband and I decided to go there to deliver my baby. On arriving, the doctor, nurse and another man told me, ‘only you can go inside, your husband will wait outside,’ and told me to take off my clothes and to put on a very short robe that left my intimacy almost uncovered.

I felt bad and humiliated and couldn’t understand what they were talking about, as they were speaking Spanish and I only know a few words of that language. They forced me to lie down… I am frightened of the health staff and how they treat you. They make you lie down and don’t hold you and leave you alone suffering with your pain.

After that we were asked to pay a penalty because I didn’t go to my complete postnatal checkups. But we don’t have money, and that is why they haven’t given me my child’s birth certificate. No, I prefer to avoid all this humiliation and suffering and will stay at home with my family next time. (Bristow et al., 2003)

Strategies For Improving Health

There are a diverse number of perspectives about which strategies are most appropriate for responding to Indigenous health inequalities. Many advocates argue for ongoing political attention on issues of Indigenous rights and broader social and economic disadvantage. In this context, issues such as land reform, the political recognition of Indigenous peoples, and support for the retention of Indigenous languages and culture are seen to be part of a broad set of strategies to improve Indigenous health and social outcomes. Others argue for strategies less explicitly framed by Indigenous rights, but advocating action that addresses the determinants of Indigenous health (such as poverty, educational reform, and programs to improve housing quality) as well as strategies to improve access to health care. These approaches are not mutually exclusive and are commonly brought together through public policy in Indigenous affairs. More specifically, it has been advocated that Indigenous health policy should link:

- Health system development and financing

- Capacity building for human resources

- Community participation

- Health care, health promotion, and disease prevention programs development and delivery

- Comprehensive integration of Western and traditional health systems

- National health information, monitoring and evaluation systems.

As an example of this, the goal of the Pan American Health Organization’s Plan of Action 1999–2002 was to promote the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples by assisting countries in ensuring equity in health and access to basic health services within the context of health sector reform (Pan American Health Organization, 2000). The work to develop those needed systems or models will be directed to three interrelated lines of action:

- Strategic planning and alliances: To support countries in the formulation and operationalization of integrated public policies and strategies for the development of health and social systems that provide Indigenous peoples with equitable access.

- Intercultural frameworks and models of care: To support countries in designing and implementing frameworks and models of care that specifically addresses Indigenous peoples’ barriers to equity in health and access to health services.

- Information to detect and monitor inequalities: To improve information collection, analysis, and dissemination on the health and social conditions of Indigenous peoples.

The diversity of Indigenous peoples is a critical issue that needs to be addressed in the development of policy and strategy. This is a challenge for the PAHO plan of action, which needs to take account of the fact that there are more than 400 different Indigenous groups within the Americas. Further to this ethnic, linguistic, and cultural heterogeneity, Indigenous peoples live in a range of different demographic contexts from remote to rural to urban.

The lack of national data on ethnicity and the scarcity of comprehensive research on health risk and disparities in many countries are serious obstacles to the establishment of regional and global plans of action on the health of Indigenous people. Health research has been criticized for its failure to include Indigenous people adequately in the research process. To be comprehensive, it should involve Indigenous people and incorporate their viewpoint. Lack of data also prevents countries from framing effective and meaningful policy in areas relating to the health of Indigenous people, a serious issue for countries where Indigenous people either represent a high proportion of the population or have a strong separate ethnic identity.

Many Indigenous groups have emphasized autonomy and self-determination and have given priority to developing an Indigenous health workforce that has both professional and cultural competence. They have also promoted the adoption of Indigenous health perspectives, including spirituality, in conventional health services. Traditional healing has been suggested as a further strategy though generally as part of comprehensive primary health care and in collaboration with health professionals.

In Canada, the adoption of the 1989 Health Transfer Policy promoted the transfer of on-reserve health services from the federal government to First Nations. In Australia, Aboriginal community-controlled health services first appeared in the 1970s because of community mobilization around issues of racism and poor access to health care.

In a number of contexts, primary health care has been a fundamental plank to the Indigenous health strategy. The devolution of service management has been one of the policy debates that have framed health policy in a number of places such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Different models of Indigenous management of services have emerged. This policy debate has also, to varying degrees, been framed in response to local Indigenous political movements that have advocated self-determination and Indigenous rights.

Global Processes And Indigenous Peoples

Many of the circumstances that shape the lives of Indigenous peoples and impact their health and social wellbeing, have arisen within the context of nation states. Political disempowerment, social marginalization, and complex social change have given rise to circumstances in which Indigenous peoples are among the poorest, unhealthiest, and most vulnerable groups in these societies. An example of the abuses of Indigenous people’s health and rights in Cambodia provides particular insight:

A few years ago a Cambodian mining company began excavating gold on land belonging to our village. Neither the company nor the district authorities had asked permission from the village elders. The mines were closely guarded day and night and we were strictly forbidden from entering the land on which the mining was taking place. Prior to the arrival of the miners we had seen little sickness in our village. Shortly after the mining started, villagers began to suffer from a range of health problems, which included diarrhoea, fever, headaches and coughing and vomiting with blood. The sickness mainly affected children but a small number of adults also were affected; 25–30 people became ill, of whom 13 eventually died. We feared that the village spirit had become angry, as outsiders were mining land, and this has been a taboo for a long time. Diang Phoeuk, Pao village Elder. (Bristow et al., 2003)

Indigenous peoples have responded to these experiences in order to enhance their well-being, both in terms of the broader social and political issues as well as the more local issues of family relationships, personal values, and behaviors. However, these social processes occur in a globalizing world. Paradoxically, Indigenous peoples who are often seen to live in small-scale societies in relatively remote locations may be the most vulnerable in relation to globalization.

For peoples who have historically been small, decentralized populations, often relying in some way on traditional forms of economic production, the impact of global ecological degradation is compounded. Increased greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity loss, deforestation and water shortage – often the result of encroaching urbanization and economic development – not only force rapid changes in those lifestyles that are traditionally linked to the land, but also result in a worsening of such basic public health necessities as safe drinking water and sanitation. In some regions, these conditions have often also been associated with an increase in diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis.

The resultant underprivileged socioeconomic stratification is further exacerbated by ongoing and increasingly global processes. These include macroeconomic policies associated with the liberalization of trade and investment protocols, international finance institutions, global trade agreements, and technological innovations. These processes may provide some opportunities in contexts where Indigenous peoples are able to negotiate with mining interests and other forms of economic development. However, in many other circumstances, Indigenous peoples tend to rely more heavily on the welfare economy, if such exists, or other more marginal economic activities. Negotiating the consequences of economic change is difficult for people who are economically and politically marginalized.

Some of the benefits of modernity and globalization (such as health care and public health services) can ameliorate its downsides. Yet many of those Indigenous peoples who live in small, decentralized, and remote circumstance often are not able to access basic health services. Where they are geographically accessible, barriers such as poverty, cultural alienation, language, as well as perceived and actual discrimination impact the capacity of Indigenous peoples to access health care on the basis of need. For instance, in the Americas an estimated 40% of the 100 million persons who are without regular access to basic health services (because of poverty and a lack of health insurance) are Indigenous, even though they only comprise an estimated 20% of the total population. A number of factors are related to the lack of access to health services. In addition, differences between Indigenous and dominant language and custom can result in a general disregard for Indigenous peoples and their beliefs, but this can also be compounded by a lack of mutual understanding and trust in mainstream services (Pan American Health Organization, 2000, 2006).

Indigenous Rights In A Global Context

There has been increasing global attention on issues of Indigenous rights since the Second World War. In part this has been a result of a number of anticolonial movements. Postwar independence movements in India, the political success of anticolonial movements in Indochina against the French and in Indonesia against the Dutch are just a few examples. Indigenous political movements in the Americas, Australia, and across the Pacific also emerged over this period of time. Anticolonial political philosophy has been shaped through the diverse contributions of a number of intellectuals such as Mahatma Ghandi, Sukarno, Ho Chi Minh, Franz Fanon, and others (Coates, 2004).

The broader human rights movement has both influenced and in turn been influenced by the thinking on the rights of colonized peoples. The United Nations’ adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 was a significant event for human rights in general, providing a context for the development of Indigenous rights. The Declaration challenged political and legal systems based on notions of cultural or ethnic superiority. The Declaration affirmed rights such as the right to equality and freedom from discrimination; the right to life, liberty, and personal security; freedom from torture and degrading treatment; the right to equality before the law; the rights to a fair trial and to privacy; freedoms of belief and religion, opinion, peaceful assembly; the rights to participation in government, to social security, to work, to adequate standards of living and to education. Further to this, the United Nations also passed a declaration that defined and outlawed genocide, any attempts to destroy peoples (Coates, 2004).

The International Labour Organization (ILO) had started working on Indigenous issues when it operated within the League of Nations prior to the Second World War. However, it was not able to draw attention to these issues because of the prevailing Western political and social contexts at this time. Nevertheless, under the aegis of the League’s successor, the United Nations, the ILO developed a draft protocol that was presented at a meeting of its General Congress in Geneva. This was the basis of ILO Convention 107, which offered directives to governments responsible for dealing with Indigenous populations (International Labour Organization, 1957). The Convention did not carry legal weight and its emphasis was placed on the provision of education, training, health, and other forms of social assistance to those groups of peoples who experienced lower standards of living and their integration into the nation-state. Issues of tribal autonomy did not, in line with prevailing political views, receive attention in this Convention.

A number of Indigenous-led political movements developed from the decades of the 1960s and 1970s, lending momentum to a further shift in international social and political attitudes to Indigenous rights (Coates, 2004). Indigenous organizations were commonly found in industrial nations in the first half of the twentieth century, but their political efficacy was limited. A general rise in Indigenous social activism from the 1960s found expression in Indigenous organizations, political movements, and activities. These political movements variously focussed on civil rights, such as in Australia where political pressure was focused in the 1960s on issues such as achieving voting rights for Indigenous Australians and the removal of the race clauses from the Australian constitution, which occurred following a referendum in 1967. The Indigenous movements also focused on the recognition of Indigenous rights, which are seen to flow from the status of Indigenous peoples as colonized people who still retain historical rights despite their political dispossession. The recognition of Indigenous land rights in Australia, Canada, Norway, and Sweden are examples of this.

These local movements in turn have raised international awareness on Indigenous rights. In 1985, the United Nations’ Working Group on Indigenous Populations began drafting a declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples in 1985. Although not intended to be legally binding on UN member states, the declaration identifies a number of Indigenous rights, including the establishment of collective rights. The 45 articles, divided into nine sections, cover a range of human rights and fundamental freedoms related to Indigenous peoples, including their right to preserve and develop their identities and unique cultural characteristics, and rights related to education, employment, health, religion, and language. It further protects the rights of Indigenous peoples to own land collectively (United Nations, 1994). On 13 September 2007 the United Nations Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples with an overwhelming majority of 143 votes in favor, only 4 negative votes cast (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and The United States) and 11 abstentions (International World Group for Indigenous Affairs, 2007).

While the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is often described as the most comprehensive statement of the rights of Indigenous peoples, a number of other international covenants and conventions also contain relevant provisions, albeit indirectly. Among these are the 1951 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which contains provisions related to causing bodily or mental harm to members of any group; the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, both of which provide for collective rights; the 1989 International Labour Organization Convention 169, which addresses the specific needs for Indigenous peoples’ human rights; the 1992 Declaration on the Rights of Persons belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities, which deals with states’ obligations toward minorities; the 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, which addresses the inherent dignity and unique contribution of peoples; and the 1997 Organization of American States’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which contains a provision for the right to self-government, Indigenous law, and cultural heritage (World Health Organization, 2001).

Bibliography:

- Alderete E (1999) The Health of Indigenous People. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Anderson I, Crengle S, Kamaka ML, Chen TH, Palafox N, and Jackson-Pulver L (2006) Indigenous Health in Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific. Lancet 367: 1775–1785.

- Beavon D and Cooke M (2003) An Application of the United Nations human development index to registered Indians in Canada, 1996. In: White JP, Maxim PS, and Beavon D (eds.) Aboriginal Conditions: Research as a Foundation for Public Policy. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia Press.

- Bourne R (2003) Invisible Lives. Undercounted, Underrepresented and Underneath: The Socio-economic Plight of Indigenous Peoples in the Commonwealth. London: Commonwealth Studies Unit.

- Bristow F, Nettleton C, and Stephens C (eds.) (2003) Utz Wachil: Health and Wellbeing Among Indigenous Peoples. London: Health Unlimited/London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Coates KS (2004) A Global History of Indigenous Peoples: Struggle and Survival. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Feiring B, Minority Rights Group Partners (2003) Indigenous Peoples and Poverty: The Cases of Bolivia, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. London: Minority Rights Group Partners. http://www.minorityrights.org/?lid=931 (accessed 17 October 2007).

- International Labour Organization Convention No. 107 concerning the protection and integration of Indigenous and other Tribal and semiTribal peoples in independent countries (1957) International Labour Conventions and Recommendations 1919–1991. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Office.

- International Work Group for Indigenous affairs (2007) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. http://www.iwgia.org/sw248.asp (accessed 19 October 2007).

- Kunitz SJ (1994) Disease and Social Diversity. The European Impact on the Health of Non-Europeans. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Maybury-Lewis D (2002) Indigenous Peoples, Ethnic Groups and the State. Needham, MA: Allyn and Baker.

- Office of the High Commission for Human Rights (1997–2002): Convention (No. 169) concerning Indigenous and Tribal peoples in independent countries. Adopted on 27 June 1989 by the General Conference of the International Labour Organisation at its seventy-sixth session. http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/62.htm (accessed 10 October 2007).

- Pan American, Health Organization (2000) Strategic Framework and 1999–2002 Action Plan: Health of the Indigenous Peoples. Washington DC: World Health Organization.

- Pan American Health Organization (2006) Gender Equity and Indigenous Women’s health in the Americas. http://www.paho.org/ English/AD/GE/Indigenouswomen.pdf (accessed 27 February 2006).

- Statistics Canada (2006) Aboriginal Peoples’ Survey 2001, Canadian Community Health Survey, 2000/01. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/profil01aps/home.cfm (accessed September 2007).

- Stephens C, Nettleton C, Porter J, Willis R, and Clark S (2005) Indigenous peoples’ health – why are they behind everyone, everywhere? Lancet 366: 10–123.

- United, Nations (1994) Statement by the President of the General Assembly at the Commencement of the International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People. New York: UN Information Co-ordinator GA/8842, 9 December.

- World Health Organization (2001) Report by the Secretariat. International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People. Fifty-Fourth World Health Assembly, 9 April 2001. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2005) World Health Report 2005 – Make Every Mother and Child Count. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/whr/2005/en/ (accessed September 2007).

- Cohen A (1999) The Mental Health of Indigenous Peoples: An International Overview. Geneva, Switzerland: Nations for Mental Health Department of Mental health World Health Organization.

- Committee on Indigenous Health (1999) The Geneva Declaration on the Health and Survival of Indigenous Peoples 1999. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Davis SH (1993) The World Bank and Indigenous peoples. Denver Initiative Conference on Human Rights University of Denver Law School. Washington DC: The World Bank.

- Global Forum for Health Research (2003) The 10/90 Report on Health Research 2000. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Howitt R (ed.) (1996) Resources, Nations and Indigenous Peoples. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press.

- International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (2001) The Indigenous World 2000/2001. Copenhagen, Denmark: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- Montenegro RA and Stephens C (2006) Indigenous health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet 367: 1859–1869.

- Ohenjo N, Willis N, Jackson D, Nettleton C, Good K, and Mugarura B (2006) Health of Indigenous people in Africa. Lancet 367: 1937–1946.

- Stephens C, Porter J, Nettleton C, and Willis R (2006) Disappearing, displaced, and undervalued: A call to action for Indigenous health worldwide. Lancet 367: 2019–2028.

- UNEP (2003) Poverty and Ecosystems: A conceptual framework a synthesis. Proceedings of the Twenty-Second Session of the Governing Council/Global Ministerial Environment Forum Nairobi Governing Council of the United Nations Environment Programme. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council (2004) Report of the Secretary-General on the Preliminary Review by the Coordinator of the International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People on the Activities of the United Nations System in Relation to the Decade. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) (1994) Draft United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations.