Sample Emotional Inhibition And Health Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Introduction

Emotional inhibition constitutes part of a maladaptive interaction between an individual and their social environment. Emotional inhibition may be classified into genetic, repressive, suppressive, and deceptive inhibition and the extreme form emotional implosion (Traue 1998). Overt emotional inhibition generally is characterized by reduced expressiveness, unemotional language, and shyness, all of which is related to dysfunctional bodily reactions and may be adaptive in a short-term social stress situation. In the long run, emotional inhibition is likely to have a harmful effect on the individual, which may occur along any of three pathways: neurobiological, social-behavioral, and cognitive. Most psychotherapeutic techniques are directed at emotional behavior and experience and focus largely on changes in intra-and interindividual emotional regulation and the construction of meaning from emotional experience.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

2. Emotion And Inhibition

Emotions may be considered transactions between individuals and their social environment. They give personal meaning to external and internal stimuli and communicate meaning from the individual to others. Emotions consist of interpretations of intero and exteroceptive stimuli, intentions, physiological patterns of arousal, and motor behavior including overt emotional expressiveness. The interaction of these different components in the individual and the social and physical environment are mediated by the central nervous system (CNS). From a regulation point of view, emotional expressiveness has two important functions: first, it serves a communicative function by facilitating the regulation of person–environment transactions and, second, the feedback function of behavioral expressions controls the intra-individual regulation of emotion. This means that an experience may be influenced indirectly by actively responding towards a negative emotional stimulus in the environment, in order to attenuate it, or directly through self-regulation. Thus, expressive behavior can serve simultaneously as a component of emotional processes and as a coping response.

Both psychoanalysis and neurophysiology advanced to the concept of inhibition in different contexts in the twentieth century. For many years, an inverse relationship between expressive behavior and autonomic responsivity has been documented, such that the inhibition of overt emotional expressiveness can lead to an autonomic over-reaction. This has been considered a significant factor in the etiology and maintenance of psychosomatic disorders. A number of early researchers in the first two decades of the twentieth century reported measurements of high physiological activity in subjects suppressing emotional expression. These studies led to the concept of internalization and externalization, where two behavioral coping styles for dealing with psychic tension were discerned: either behaviorally, outwardly directed, or physiologically, within the individual. According to this concept, the term ‘internalizer’ describes a person exhibiting a low level of overt expressiveness under stress yet a high level of physiological excitation, whereas an ‘externalizer’ is characterized by high expressiveness and a low level of physiological expressiveness in social situations. Different health models explain on internalizing and externalizing in terms of stress and coping or in terms of inhibition as physiological work. Over time, the work of inhibition acts as a low-level cumulative stressor. As with all cumulative stressors, sustained inhibition is linked to increases in stress-related diseases, and various other disorders such as cardiovascular and skin disorders, asthma, cancer, and also pain (Traue and Pennebaker 1993).

3. The Model Of Inhibition And Health

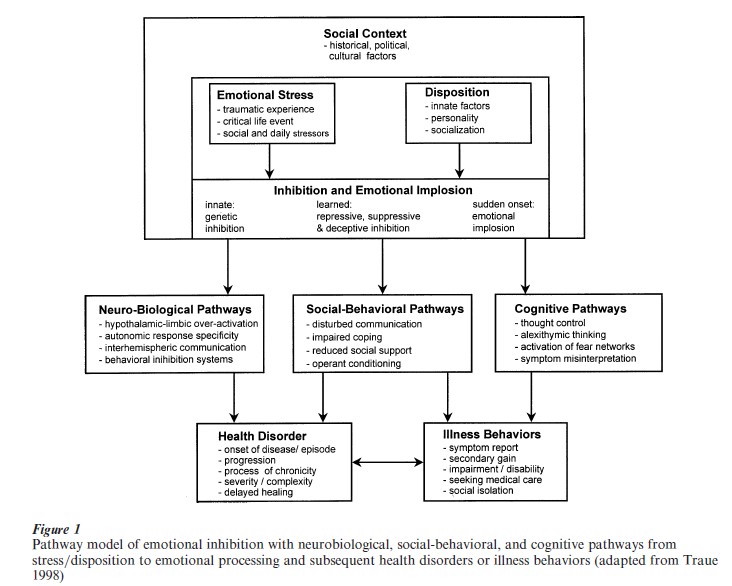

A model explaining how emotional stress, under a given social situation, can trigger or modulate health disorders is described below (see Fig. 1). Health disorders and illness behavior are conceived as different, but related, processes, and distinct mechanisms may contribute dependently and independently to different aspects of a given disorder and its behavioral consequences (Traue 1998).

On a phenomenological level, emotional stress can occur on a severity dimension ranging from daily stressors, through more traumatic life events, to more chronic or severe psychotrauma. A common underlying factor in such situations is that each has to be coped with by the individual. Emotional stress can be considered to be processed by way of an ‘inhibitionimplosion’-dimension (to implode means to collapse or cause to collapse inwards in a violent manner as a result of external pressure), modulated by dispositional factors (innate, personality, and socialization).

Of particular importance are innate and socialization factors. Possible individual differences in hypothalamic mechanisms and opioidergic pathways corresponding with increased vulnerability to stress have been suggested. Emotional processing relating to the inhibition-implosion idea has been discussed in relation to several topics such as control, suppression, Type C personality, repression, alexithymia, or ambivalence. Each of these concepts covers different aspects of overt emotional expressiveness from a personality or coping perspective. Inhibition is the most general term for the incomplete processing of emotional stress when these stressors induce bodily changes (physiological, endocrinological, or immunological) and the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processing are dysfunctional such that subjective experience and spontaneous expression of emotions and action tendencies are separately or simultaneously attenuated and intra- and interpersonal regulation is disturbed. This process may be the result of innate or acquired behavior.

3.1 Classification Of Emotional Inhibition

A classification of involved mechanisms differentiates between genetic, repressive, suppressive, and deceptive inhibition.

Genetic inhibition describes the genetically determined basis of behavioral inhibition. Studies working with young children have classified those children who were least able to initiate interaction in a social situation with other children and adults as behaviorally inhibited. Most children’s degree of behavioral inhibition has been shown to be stable over a period of five years. In those children classified as inhibited, increased levels of arousal, norepinephrine, and salivary cortisol have been found.

Repressive inhibition refers to emotional processing with attenuated subjective experience of emotional arousal. Emotionally expressive responses in repressive inhibition could be based solely on the cognitive interpretation of the situation and are organized nonspontaneously. The individual, being unable to feel their own arousal, processes insufficient responseinformation for an appropriate response, which in turn decreases the need to express emotions or cope with an emotional stressor. In addition, the cognitive interpretation of the situation without the emotional component may be wrong or misleading. Prolonged bodily arousal and impaired coping could result. Repressive coping style is the best known model for repressive inhibition.

Suppressive inhibition is best circumscribed by suppression of emotional arousal. The emotional arousal is recognized by the individual, but spontaneous expressive and cognitive behaviors are suppressed involuntarily or habitually. Suppressive inhibition of emotions results from interactions between innate factors and socialization. For example, if individuals show increased responses under stressful encounters, they are prone to socialization conditions of punishment and negative reinforcement, initiating a learning history with decreases in spontaneous expressiveness and increases in bodily arousal.

Deceptive inhibition describes the phenomenon whereby individuals under emotional stress, aware of their bodily reactions and their urge for expressiveness, can suppress this need voluntarily or try to present a false response to a receiver. Whether an individual is pokerfaced or displays a false emotional response, such inhibition requires psychological energy, reducing the individual’s coping capacity and providing additional stress.

In reviewing the psychophysiological and psychosomatic data, it might appear that emotional inhibition is always harmful. However, it should be noted that although the correlations between bodily processes and the above four forms of inhibition support such a notion, in certain circumstances inhibition could be beneficial for the individual and his her relationship with the social environment. Inhibition becomes toxic when it is related, first, to physiological, endocrinological hyperarousal or immunological dysfunction, second to long-standing disregulation of emotions within the individual on a cognitive and behavioral basis, and third, if inhibition disturbs the individual’s social relations.

Inhibition represents a risk factor for health under normal stressors. If the severity of the stressors is dramatically high, the mental and physical health consequences are inevitable. In traumatic stress situations like rape, criminal bodily attacks, or torture the victim may well lose control over strong emotional responses. The emotional responses of horror, panic, and loss of control could literally cause a violent breakdown in the mental and bodily systems. Such an emotional implosion (Traue 1998) is observable in the symptom pattern of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): cognitive and behavioral avoidance of trauma stimuli, numbing of general and emotional responsiveness (emotional anesthesia), detachment from other people, persistent symptoms of arousal like disturbed sleep, exaggerated startle response and somatic complaints. In addition, persons with PTSD suffer an increased risk of social phobia, major depressive and somatizing disorder (DSM-IV, American Psychiatric Association 1994).

The psychological, physical, and social symptoms in PTSD are a form of emotional processing involving an extreme form of inhibition. While inhibition generally develops over a long time span through interaction between innate and socialization factors, implosion can occur in a very short time as a result of a single and extreme man–made stressful event.

4. Pathways From Emotional Inhibition To Health Disorders And Illness Behaviors

Emotional stress modulated through innate, personality, and socialization factors can trigger, maintain, or worsen health disorders and related illness behavior through neurobiological, social-behavioral, and cognitive pathways. With respect to illness behaviors, the pathways include biases in symptom reporting, secondary gain by presented symptoms, subjective feelings of being impaired, pressure to seek medical help and social isolation.

4.1 Neurobiological Pathways

Emotional inhibition is strongly neurobiologically based. The behavioral inhibition system and the behavioral activation system have been discussed as possible neurobiological structures. Empirical evidence from between-subject studies shows that inhibited, repressed, or suppressed emotional expressiveness is linked to greater autonomic arousal, both under conditions of emotion induction and voluntary deception. There is rich empirical evidence for neurobiological correlates of inhibition in respiratory, cardiovascular, muscular, digestive, and immune functions. Immune functioning is of particular interest because it is the immune system that may be relevant in all sorts of infectious, allergic, and neoplastic illness processes. Inhibited style of processing upsetting events can compromise immune functions, resulting in higher serum antibody titers, decreased monocytes counts, and poorer natural killer cell activities. Other fields of research relevant to the neurobiological pathways of inhibition include hypothalamic-limbic over activation, prolonged activation of physiological response specificity, hemispheric brain lateralization of emotion processing and faulty interhemispheric communication, the neuroregulation of action, and the behavioral activation and behavioral inhibition systems.

4.2 Social-Behavioral Pathways

Several social-behavioral pathways connect inhibition-implosion to health disorders and illness behaviors. First of all, neurobiologically innate factors (shyness, behavioral inhibition, hypersensitivity, introversion) are superimposed by classical and operant conditioning in the socialization of an individual. Since individuals with these characteristics in early childhood are conditioned more easily, the process of socialization is of greater importance to them than it is to others. Under critical developmental conditions, the gap between emotional expressiveness and physiological hyperactivity may increase. A lack or deficit in emotional expressiveness will hinder interpersonal communication. It is thought that deficits in interpersonal communication disturb the development of emotional competence that is important for sharing experiences, maintaining psychological and physical contact, and adapting to the social environment (Rime 1995). These are deficiencies in the healthy coping competencies that have been termed emotional intelligence. Other consequences of inhibited emotional expressiveness are disturbed social relations resulting in social isolation and a disrupted social support network.

Normally, persons respond to emotion-evoking stimuli with emotional expression, and such reactive expression is created by facial muscle activity and movements with reafferent neuronal signals in the CNS, which contribute to the individual’s emotional experience. Subjective emotional experience does not, however, depend exclusively on this nervous input as claimed in the facial feedback hypotheses, but feedback does contribute positively to sensitivity towards the physiological aspects of emotion. If this sensitivity is disrupted, an individual will not perceive adequately increased muscle tension or other autonomic nervous system (ANS) reactions caused by stress, and consequently will not initiate healthy relaxing behavior. It has been demonstrated that the hypothesis of deficient perception of muscle tension holds for myogenic pain. These patients were significantly less able to judge the extent of their muscle strain than were controls.

It is conceivable that, under unfavorable circumstances, expressive behavior for mainly negative emotions like anger and aggressiveness is punished socially and thus justifiably avoided. The suppression of expressive behavior can be achieved by an additional increase in muscle activity. Such avoidance behavior or inhibition is very adaptable in the short term, and it helps to modify a socially stressful situation. This reduction of emotional expressiveness is conditioned by the learning mechanism of negative reinforcement (the avoidance of punishment).

4.3 Cognitive Pathways

Memories and thoughts of emotional stressors are generally unpleasant. Increasing severity of the stressful encounter makes imagining the event painful or even unbearable in the case of traumatic experience. Most individuals attempt to suppress the thoughts surrounding traumatic events. As soon as the inhibition work begins, the urge to distract oneself and the mental energy put into this process fuels the images. Consequently, triggered intrusions and unwanted thoughts make life more stressful than before. In addition, thought control interferes with natural ways of coping such as sharing the experience with important others and thinking through the event. Therefore, inhibition may be dangerous because it hampers the individual who has suffered a critical life event in resolving the stressful experience cognitively and behaviorally.

As part of the inhibition process, individuals may tend to exclude the emotional content of the stressful encounter from their language representation of the event, called alexithymia, or low level thinking style. Although this may help to avoid negative emotionality in the short term, it hinders complete processing and integration of the stressful experience. The lack of integration into the self-concept makes an individual prone to the activation of fear networks. Finally, impaired or unfinished cognitive processing can make an individual prone to misinterpreting bodily symptoms. Instead of understanding bodily reactions as part of emotional responses, the individual conceptualizes the bodily reactions as symptom patterns and seeks medical help for illnesses. Badly advised medical treatment procedures result in iatrogenic diseases trapping the individual in a vicious cycle. Cognitive appraisal of a situation depends partly on facial feedback as a source of emotional information. When the expressive components of emotional reactions are systematically repressed by inhibition, the individual ‘unlearns’ an accurate assessment of stressful circumstances. This learning mechanism occurs because the estimated load of a stress situation is dependent not only on external features of the situation, but also on the subjective experience of stress conditioned reactions. When, however, an inhibited person takes bodily reactions into account in the evaluation of a situation, their judgment will be impaired when the original physiological components of mainly negative emotions are interpreted as ‘symptoms.’

In clinical studies, psychosomatic patients suffering, for example, from headaches have been found to report significantly lower stress levels than a control group, but showed nearly twice as much neck muscle tension as the controls. Although the arousal and muscle tension data indicated higher levels of stress, patients were unable or unwilling to report those stressors. It would appear that patients tend to interpret their stressors in terms of bodily symptoms, rather than underlying levels of stress.

5. Rituals And Therapeutic Interventions

Most societies seem to contain at least some implicit knowledge that emotional inhibition has negative health implications. The conflict resulting from the need for emotional regulation on the one hand and the need for disclosure, sharing, and catharsis on the other hand leads to a variety of cultural phenomena to solve this conflict. These include older universal cultural rituals (such as rituals of, grief, or lament), or religious acts such as confessions. The Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, where people have been going for centuries to deliver a written prayer, is possibly an example of an ancient disclosure phenomenon. Contemporary Western societies have introduced psychotherapy for enhancing emotional expressiveness. Here, talking or writing about emotions is encouraged, as is the acting out of emotions in role-plays. Assertiveness training aims at effective expression of emotion and catharsis-based techniques like confrontation are modern remedies for anxiety, PTSD, and the like. All of these techniques seem to have in common that they are directed at the construction of meaning from emotional experience. Culture, which may be construed as a subset of possible meanings, is therefore a very important mediating factor in this process. New approaches to cross-cultural psychology have proposed intercultural differences in emotional inhibition based on dimensions like masculinity–femininity, collectivism–individualism, uncertainty avoidance, and power distance.

Bibliography:

- American Psychiatric Association 1994 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

- Rime B 1995 Mental rumination, social sharing, and the recovery from emotional exposure. In: Pennebaker J W (ed.) Emotion, Disclosure, and Health. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 271–92

- Traue H C 1998 Emotion und Gesundheit. Die psychobiologische Regulation durch Hemmungen (Emotion and Health. Psychobiological Regulation by Inhibition). Spektrum, Heidelberg, Germany

- Traue H C, Pennebaker J W (eds.) 1993 Emotion, Inhibition and Health. Hogrefe & Huber, Seattle, WA