Sample Mortality And The HIV/AIDS Epidemic Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. HIV/AIDS And Mortality

This research paper examines the effect that the HIV/AIDS epidemic has had on mortality levels in several regions of the world. We emphasize conditions experienced in countries where the epidemic has had the strongest impact.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

2. An Exceptional Occurrence In The Midst Of Unprecedented Progress

The occurrence of HIV/AIDS is an exceptional event associated with large mortality increases that, paradoxically, takes place at the end of a century characterized by the most significant feat of human history: the unprecedented lengthening of life.

Starting approximately in 1850 the world as a whole began to experience gradual but consistent increases in life expectancy. This process became a true revolution, and in less than two centuries, an infinitesimal fraction in the metric of human evolution, the average survival of the species as a whole was greatly increased. The speed and magnitude of gains in survival varies by regions and, as a result, there is still great heterogeneity in current mortality levels.

A pretransitional mortality regime, typically prevailing during the period before 1850, made human survival a highly uncertain event due to high infant and child mortality and, more generally, to very low levels of life expectancy. Between one in four and one in five live births would not reach their first birthday, whereas a member of the population would, on average, live not longer than 35–40 years. Furthermore, the life expectancy prevailing at any one time was highly variable. This is because mortality levels were very sensitive to climatic changes, variations in economic performance, epidemics, wars, and population movements. Pretransitional mortality regimes were not particularly robust.

A modern, post-transitional, mortality regime is characterized by higher and normally increasing values of life expectancy and by added robustness since the life expectancy that prevails in any one year is subject to less uncertainty than in pretransitional mortality regimes. This does not mean that variability around a trend of increasing life expectancy is not observable. Indeed, the twentieth century has seen its share of conditions that induced deceleration of gains in survival or reversals in an otherwise regular increasing trend. Examples are the flu epidemic of 1918–19, the two World Wars and their aftermath, the Great Depression of 1929, and the China famine of 1956–60. However, these episodes of higher than average mortality are rare. Furthermore, when they occur, they are generally characterized by effects that can be offset in short periods of time. The aftermath of a mortality crisis or of a period of deceleration of gains is usually followed by ressumption of the trend prevalent prior to the events that led to the crisis or deceleration. Thus, modern mortality regimes are less volatile and more resilient, particularly in more developed areas, than they were in the past.

Two exceptions to this absence of volatility stand out. The first is the post-1970 experience of Eastern Europe where the gradual trend toward higher levels of life expectancy has been arrested and, in some cases, reversed. The main factors behind these trends in the region are not exactly new, but their effects were not felt with full force until the breakup of the Soviet Union. Since the late 1970s and early 1980s, mortality in infancy, early adulthood, and among mature adults has progressed very little, and in some cases has increased.

The second exception is the case of HIV/AIDS. The epidemic has had an impact in many world regions but only in sub-Saharan Africa have its effects being strong enough to thoroughly dismantle a regime of survival gains that took decades to achieve. The effects of the epidemic will mark these societies for a long time to come, certainly for at least the next 50 years. The losses to human life associated with the HIV/AIDS epidemic are formidable, so huge that they dwarf the consequences associated with all other crises in the twentieth century and many of those observed in other centuries.

3. Characteristics Of The HIV/AIDS Epidemic

HIV is a virus transmitted via heterosexual and homosexual contact, blood transfusions, needle puncturing and, finally, perinatally, from mother to child. The virus is characterized by two main features. The first is that it has a long but variable incubation time during which infected individuals are asymptomatic and can, therefore, unwittingly infect others. The second feature is its ability to completely disable the immune system and, as consequence, to induce extremely high levels of mortality once the disease becomes symptomatic (ARC or AIDS). If HIV’s incubation times were short, its impact would be more limited than it actually is. This is because infected individuals would have fewer opportunities to infect others, either as a result of higher lethality or because of more effective societal containment.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic adopts two principal patterns. The first is when the virus spreads mainly in well-bounded but relatively small communities of individuals who practice homosexuality or are intravenous drug users. The second pattern emerges when the epidemic is transmitted via heterosexual contact as well as perinatally. The first pattern has been characteristic of Western and Northern Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand. The second pattern established firm roots in sub-Saharan Africa and has been making inroads in India, Thailand, and Cambodia. A hybrid pattern, a combination of the first and second, is characteristic of Eastern Europe, Brazil, Haiti and, to a lesser extent, of other countries in Central America.

HIV prevalence among adults varies widely by major world regions. As of 1995 sub-Saharan Africa experienced levels close to 2.5 percent, whereas all other regions had levels below 1 percent. These figures conceal a great deal of heterogeneity. For example, as of 1997 prevalence levels in sub-Saharan Africa were as low as 1.5 in Benin and as high as 21.5 percent in Zimbabwe. Similarly, whereas in India adult prevalence was below 1 percent, in Thailand it is estimated to exceed 2 percent. Finally, in Brazil levels of adult prevalence are below 0.51, whereas in Haiti they exceed 4.1 percent.

HIV prevalence has been increasing in Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America. Instead, after an early start there, levels of prevalence have begun to taper off in North America and Western Europe.

4. Impact On Mortality Levels

Other things being equal, the spread of the disease will tend to occur more rapidly and the prevalence levels will attain higher values in populations where the second pattern prevails. This is because the relative size of the population exposed to heterosexual contact (males and females) is usually larger that the relative size of the population exposed to homosexual contacts or intravenous drug use. By the same token, the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on mortality levels will be higher in societies where the second pattern becomes established. That is, equivalent levels of adult HIV prevalence translate into radically different effects on mortality depending on the pattern of spread of the disease. This is because the mortality effect in countries with the second pattern will be felt not just at youngadult ages but also among infants and children. An increase in infant mortality leads to much larger decreases in life expectancy than those induced by equivalent increases of mortality at other ages.

Although cumulated mortality associated with AIDS reflects a formidable toll, the actual impact on life expectancy and crude death rates are sizeable only in sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, while in sub-Saharan Africa death rates will increase by an estimated 13 percent in the year 2005 (Bongaarts 1996), the increase will be of the order of 2 percent in North America, 1 percent in Western Europe, 4 percent in Asia, and 6 percent in Latin America. By the time Asia and Latin America feel most of the epidemic’s impact on mortality, their experience will be closer to that of sub-Saharan Africa than to Western Europe or North America.

Despite the strong impact of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, it is unlikely that the increase in mortality referred to above will induce substantial decreases in the natural rate of increase. The exceptions to this are cases where HIV/AIDS also induces substantial reductions in fertility.

5. Losses In Life Expectancy

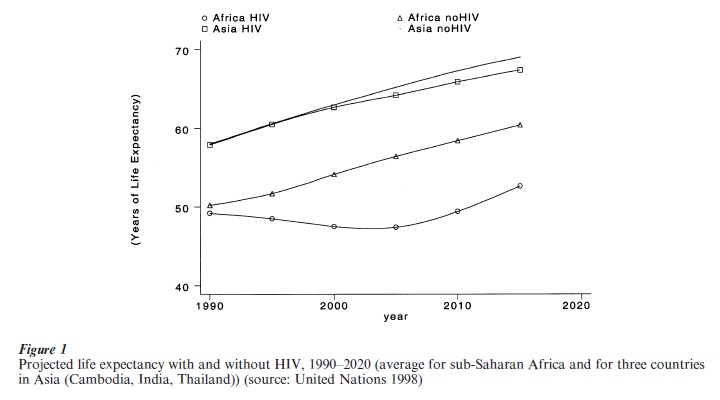

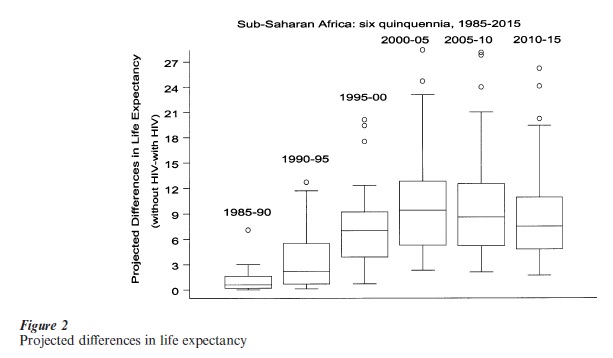

The potential losses of years of life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa are staggering. During the period 1985–90, the epidemic induced an average loss of about one year of life expectancy. During the period 2010–15 the average loss is projected to be about 7.8 years (United Nations 1998). Figure 1 displays life expectancies that would be observed in the absence of HIV/AIDS and values projected to occur with HIV over six quinquennia, starting with 1985–90. The figure includes a curve for the average of sub-Saharan Africa and for the average of three countries of Asia (Cambodia, India, and Thailand). Projected values experience a rebound, reflecting decreasing incidence of HIV/AIDS. Though useful, the figure conceals substantial heterogeneity. Thus, in sub-Saharan Africa there are countries such as Bostwana and Zimbabwe where the difference between life expectancy with and without HIV will attain values larger than 15 years before HIV incidence rates reach a maximum. This heterogeneity in sub-Saharan Africa is captured in the box-plots in Fig. 2, which portray the trajectory of the median, range, first and third quartiles and individual outliers of the distribution of projected values of life expectancy.

Projected levels of life expectancy in the presence of HIV/AIDS will not occur with certainty. This is because we are not quite sure about current levels of prevalence and because we rely on unproven assumptions about the incubation process (timing and about the ultimate fraction of the infected population who actually will contract AIDS).

With this caveat in mind, we note that losses of life expectancy of the magnitude uncovered before and the very long period of time over which they are spread suggest extreme conditions, comparable only to the worst crises episodes experienced by human societies.

6. Overall Societal Impacts

Irrespective of what the typical pattern of spread of the epidemic is, all societies affected by it will experience important social, economic, and political disruptions. However, nowhere will the impact be as large as it is estimated to be in areas of sub-Saharan Africa, where levels of adult HIV/AIDS prevalence are over 5 percent. In societies with high prevalence of other infectious diseases, HIV disables individuals before full onset of AIDS. This can have a number of effects, such as reduced productivity in the labor force, school absenteeism, and inability to fulfil paternal or maternal roles as caregivers. The impact on the economy, on physical and human capital will be enormous. Second, the mortality effects will deplete the most productive segment of the population and, in some cases, will be felt particularly hard in social groups who are influential in the political and economic life of a country. Third, and perhaps most disturbingly, the mortality impact will have a multiplying effects on future generations. Indeed, an increase in adult mortality will lead to increased widowhood and orphanhood, family disorganization and disruption of intergenerational transfers (Palloni and Lee 1992). Young children will be deprived of care, will forego education and training in order to survive, and may be even forced to engage in behaviors and activities that increase the risk of contracting the disease.

7. The Future

As a result of intense educational campaigns and of changes in individual behaviors, the HIV/AIDS epidemic appears to be tapering off in North America and Western Europe. This is not the case in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Latin America. We expect that incidence will continue to increase, albeit at a decreasing rate, well within the first decade of the twenty-first century before it reaches a maximum and starts to decline. If so, HIV/AIDS will be with us for a long time to come, and its impact on mortality will not cease until past the year 2020. Of all the catastrophic events in the past that altered mortality levels, the HIV/AIDS epidemic will surely stand as one of the most devastating of them all.

Bibliography:

- Bongaarts J 1996 Global trends in AIDS mortality. Population and Development Review 22: 21–46

- Palloni A, Lee J Y 1992 Families, women, and the spread of HIV/AIDS in Africa. Population Bulletin of the United Nations 33: 64–87

- United Nations 1998 The Demographic Impact of HIV/AIDS. Population Division, United Nations