Sample Behavioral Treatment Of Obesity Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Introduction

1.1 Definition

Cognitive behavior therapy is the leading treatment for obesity because it produces significant weight loss with minimal adverse side effects. Treatment components include a low-fat, balanced-deficit diet of approximately 1200–1800 kcal per day and a gradual increase in physical activity to 30 min per day. Patients keep extensive records of food intake and physical activity and use stimulus control procedures, such as limiting places and activities associated with eating. Modification of negative cognitions is increasingly used in treatment (Brownell 2000).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The mechanics of treatment are straightforward. Weekly individual or group sessions are provided for an average of 20 weeks. Bimonthly follow-up visits are provided to facilitate the maintenance of weight loss. University-based programs treat 8–20 patients in a group, but commercial programs may include as many as 100 people. Sessions are highly structured, and manuals frequently are provided to participants. Although the clinician typically introduces a new weight control skill each week, most of the session is spent reviewing homework, setting specific behavioral goals, and helping patients find solutions to barriers (Wadden and Foster 2000).

1.2 Scope Of The Paper

This research paper briefly reviews the development of the behavioral treatment of obesity. It examines short-and long-term results of treatment and considers methodological issues and future directions for research.

2. History Of Obesity Treatment

2.1 Treatment In Ancient Greece Through The Early Century

The treatment of obesity can be traced back to Hippocrates in Ancient Greece. His ‘remedy’ consisted of hard labor, sleeping on a firm bed, eating once a day, consuming fatty foods, and working naked as many hours a day as possible. From the time of Hippocrates to the twentieth century, obesity treatment remained remarkably consistent, targeting various aspects of food intake and exercise. This consistency is somewhat surprising in view of the ever-changing views of the etiology of obesity during this time (see Brownell 1995).

The greatest shift in treatment occurred in the 1940s and 1950s when psychoanalysis dominated mental health practice in America and other countries. Psychoanalysis contended that psychiatric problems were the expression of unconscious sexual or aggressive impulses. In this view, obesity was regarded as a manifestation of a basic personality problem that could involve oral fixation or efforts to compensate for feelings of sadness or inadequacy. Resolution of these conflicts was thought to be necessary for the patient to lose weight. Surprisingly, despite the lack of empirical support for this approach, psychodynamic therapy is still used to treat obesity. For a more extensive review of historical origins of obesity, see Bray (1990).

2.2 Founding And Development Of Behavioral Treatment Of Obesity

With the emergence of behavioral treatment in the 1960s, the focus shifted from internal, unconscious conflicts to the external behaviors associated with obesity. Ferster and co-workers were the first to suggest the application of behavioral principals to obesity treatment (Ferster et al. 1962). In this conceptualization, obesity was viewed as a learned dis-order that could be ‘unlearned’ through specific behavioral principles. The main principles were operant conditioning (i.e., a behavior becomes more or less frequent as a function of the consequences it produces) and classical conditioning (i.e., a stimulus that is repeatedly paired with an unconditional stimulus will eventually provoke the same response as the unconditional stimulus). Thus, obesity resulted when a neutral stimulus (i.e., activities, people, places, times of day) were paired with eating and, subsequently, elicited eating in the absence of hunger. Appropriate eating habits and weight loss would be achieved with the use of stimulus control (i.e., limiting the activities, conditions, and people associated with eating) and reinforcement contingencies (i.e., pairing negative consequences with overeating and positive ones with eating appropriately).

The first empirical evaluation of behavioral treatment was published by Stuart (1967). Stuart’s one-year program, which provided 26 half-hour individual sessions, produced an impressive average weight loss of 17.2 kg (about 19.2 percent of initial body weight) in eight obese individuals. The success of this program sparked a revolution in the treatment of obesity. Dozens of clinical trials followed in the next decade.

Over time, the content and process of treatment became more refined. In the 1970s, group behavioral treatment of obesity emerged, in large measure be- cause it provided an economical and efficient means for graduate students to collect dissertation data. Regardless of its origin, group treatment caught on quickly and, today, is the standard in hospital practice and clinical trials. The 1980s also witnessed significant changes, as investigators sought new ways to induce larger weight losses and improve the maintenance of weight loss. Very low calorie diets were introduced, and exercise training became an increasingly important treatment component. Maintenance strategies, in addition to exercise, included the use of frequent (i.e., biweekly) follow-up visits and social support.

Several theorists have made a major impact on the field. Keesey and Stunkard’s notion of a biological ‘set point,’ around which body weight was regulated, suggested that there were biological limits to weight loss. Bandura’s self-efficacy theory and Marlatt and Gordon’s relapse prevention model provided new methods to induce and maintain changes in eating and activity habits.

2.3 Evolution And Spread Of Behavioral Treatment Of Obesity

Today, behavioral treatment is considered integral to any comprehensive weight management program. It is combined with pharmacotherapy and surgical treatments for obesity and is used in commercial weight loss programs throughout the world. The principal components have remained the same, including self-monitoring, stimulus control, cognitive restructuring, and education in nutrition and exercise. However, emphasis increasingly has shifted toward viewing obesity as a chronic disorder that requires long-term treatment, to help individuals sustain changes in their eating and activity.

3. Research On Behavioral Treatment Of Obesity

3.1 Short-Term Results

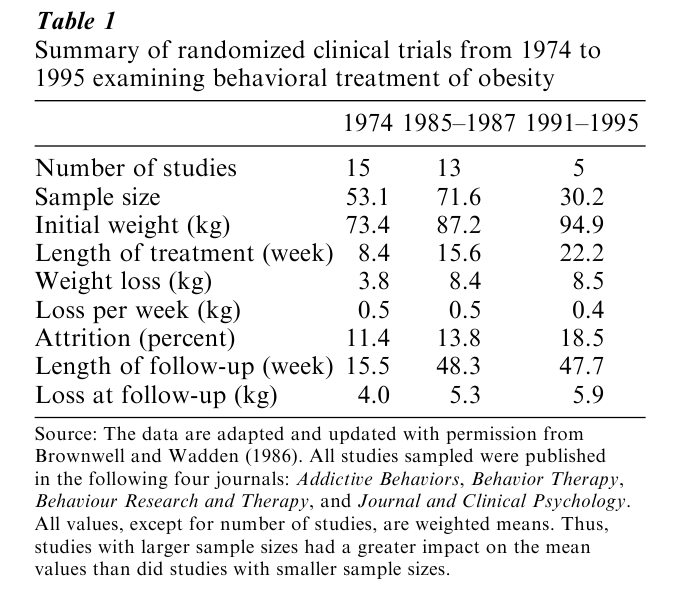

Randomized control trials conducted in the 1970s showed that behavior therapy was consistently superior to comparison conditions, and produced an average loss of 3–4 kg in eight weeks (Table 1). As both the length and content of treatment expanded in the 1980s, weight losses nearly doubled (Table 1). However, the rate of weight loss remained unchanged at 0.4–0.5 kg per week, suggesting that longer treatment, not changes in its content, produced the greater weight loss. With longer treatment, attrition rates have increased, but still remain impressively low at, that is, 15–20 percent. A standard 20-week treatment currently produces an average loss of 8.5 kg, equal to a 9 percent reduction in initial body weight. Weight losses are associated with significant improvements in cardiovascular and psychosocial health.

3.2 Long-Term Results

The overarching problem with behavioral treatment has been impaired maintenance of weight loss (Wilson 1994). In the year after treatment, patients typically regain about 30–35 percent of their weight loss (Table 1). Weight regain generally increases over time. In 3–5 years, 50 percent or more of patients return to their baseline weight (Wadden and Foster 2000).

Long-term (i.e., 52–78 week) weekly or every-other-week group behavioral sessions promote the maintenance of weight loss. On average, patients maintain their full end-of-treatment loss as long as they attend maintenance sessions. Unfortunately, attendance of these sessions declines over time and, after treatment ends, patients tend to regain weight (Perri et al. 1988). Thus, maintenance sessions appear only to delay rather than to prevent weight regain.

A small minority, however, of obese individuals are able to lose weight and keep it off. The National Weight Control Registry is comprised of individuals who have lost a minimum of 13.6 kg (i.e., 30 lbs), using a variety of methods, and maintained the loss for at least one year (Klem et al. 1997). Participants have reported that they consume a low-calorie diet (1300– 1800 kcal per day) and walk the equivalent of 45 kilometres per week. Based on these findings, it appears that behavioral treatment does target the essential components for long-term weight control. However, further research is needed to identify methods to facilitate patients’ long-term adherence to a low-fat, low-calorie diet and high-activity lifestyle.

4. Methodological Issues In The Conduct Of Research

4.1 Sampling Issues

Sampling bias is a major criticism of the behavioral treatment of obesity. The typical patient in a weight control study is 100 kg, educated, middle-aged, Caucasian, and female. Patients are likely to be highly motivated, as reflected by their willingness to complete the multiple questionnaires and medical tests required in a research study. Clearly, this subject profile does not reflect the heterogeneity of overweight and obese people in the general population. It is possible that if behavioral treatment were delivered to randomly selected members of the general population, they would achieve a less favorable outcome because of potentially lower motivation. Alternatively, they might achieve a better outcome given that participants in clinical trials are usually thought to have the most refractory obesity. The generalizability of findings from research trials needs to be determined. Similarly, studies are needed to determine whether increasing the cultural appropriateness of treatment will improve outcomes in minority populations (Kumanyika et al. 1992).

4.2 Assessment Issues

Behavioral scientists were first attracted to research on obesity because weight provided a ‘simple’ outcome measure. Thus, the ‘success’ of behavioral interventions typically has been assessed by the amount of weight lost. Most investigators believed that the greater the weight loss, the greater the success. However, the emphasis on achieving large weight losses, or ideal weight, has declined in the past decade with the realization the most patients cannot achieve more than a 10–15 percent reduction in initial weight. Thus, reaching ideal weight has given way to the achievement of a healthier weight. Losses of 5–15 percent of initial weight frequently are sufficient to improve weight-related health complications.

The shift from weight loss to health-related outcomes has important implications. For example, if behavioral treatment failed to produce long-term weight loss, it might succeed in modifying other outcomes associated with improved physical or mental health. Reducing fat intake, increasing physical activity, and improving coping skills may produce benefits beyond those obtained through weight loss alone. Blair and co-workers, for example, have shown that individuals who are fat but physically fit have a lower rate of all-cause mortality that do persons who are lean but unfit (i.e., sedentary). Thus, additional efforts are needed to expand the definition of ‘successful’ treatment to include multiple health domains. The Study of Health Outcomes of Weight Loss (SHOW) is a 6,000 person, multicenter, 12-year trial that will assess whether weight loss (and or improved fitness) decreases mortality in obese individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Assessment of eating and activity habits has always been problematic. Obese, as well as lean, individuals underestimate their food intake while overestimating their physical activity. Difficulty in measuring these variables has slowed progress in understanding the etiology of obesity and in identifying possible behavioral phenotypes. A new generation, however, of pedometers and accelerometers provides more accurate estimates of daily physical activity. Similarly, the doubly-labeled water method yields very accurate estimates of total energy expenditure and, thus, of food intake. These methods will allow investigators to assess more clearly both the biological and genetic factors that contribute to obesity.

4.3 Selection Of Research Questions

Dozens of studies have demonstrated the benefits of the behavioral weight loss ‘package.’ However, it remains to be determined which of the many treatment components (e.g., cognitive techniques, relapse-prevention, self-monitoring, stimulus control) contributes to success. A few preliminary studies have attempted to identify the active ingredients in behavioral treatment. One study found that cognitive treatment did not significantly improve the effects of standard behavioral treatment (Collins et al. 1986). Another suggested that adding relapse prevention training to long-term treatment did not improve outcome compared to long-term care alone (Perri 1992). Additional controlled studies are needed to replicate these findings and determine the critical ingredients of the behavioral package. This could have important implications for treatment delivery if, for example, it were found that having patients simply ‘weigh in’ each week and submit a food record was as successful as having them attend 90-minute group sessions.

5. Future Directions

Investigators must continue efforts to improve the maintenance of weight loss. Combining behavioral treatment with pharmacologic agents, including sibutramine or orlistat, could well facilitate this goal. However, behavioral methods to prevent relapse must be examined, such as improving body image and/or promoting patients’ acceptance of more modest weight losses.

Further research is also needed on the effects of tailoring treatments to subgroups of the obese population. Some individuals, for example, may do better with group treatment and others with individual therapy. Some patients may respond best to portioncontrolled diets and others to diets of conventional foods. People with body image concerns or binge eating might benefit most from treatments focused on these disturbances. Research in this area is in its infancy and will require the identification of behavioral phenotypes, as noted earlier.

Finally, as the prevalence of obesity increases, public health campaigns will be needed to prevent the development of this disorder by attacking the ‘toxic’ environment that lies at the root of the epidemic. Technical advances, such as internet-based programs, may help broaden the impact of prevention and treatment efforts. Additionally, integrating treatment into community settings, primary care practices, and workplaces are needed. Ultimately, a partnership among multiple sectors of society will be required to target the many factors that have contributed to the fattening of industrialized nations (WHO 1998).

Bibliography:

- Bray G A 1990 Obesity: Historical development of scientific and cultural ideas. International Journal of Obesity 14: 909–26

- Brownell K D 1995 History of obesity. In: Brownell K D, Fairburn C G (eds.) Eating Disorders and Obesity: A Comprehensive Handbook. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 381–5

- Brownell K D 2000 The LEARN Program for Weight Management 2000, 8th edn. American Health Publishing Company, Dallas, TX

- Brownell K D, Wadden T A 1986 Behavior therapy for obesity: Modern approaches and better results. In: Brownell K D, Foreyt J P (eds.) The Handbook of Eating Disorders: The Physiology, Psychology, and Treatment of Obesity, Bulimia, and Anorexia. Basic Books, New York

- Collins R L, Rothblum E D, Wilson G T 1986 The comparative efficacy of cognitive and behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity. Cognitive Therapy Research 10(3): 299–318

- Ferster C B, Nurnberger J I, Levitt E B 1962 The control of eating. Journal of Mathetics 1: 87–109

- Klem L, Wing R, McGuire T, Seagle M, Hill O 1997 A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 66: 239–46

- Kumanyika S, Morssink C, Agurs T 1992 Models for dietary and weight change in African American women. Ethnicity and Disease 2: 166–75

- Perri M G 1992 Improving maintenance of weight loss following treatment by diet and lifestyle modification. In: Wadden T A, Van Itallie T B (eds.) Treatment of the Seriously Obese Patient. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 456–77

- Perri M G, McAllister D A, Gange J J, Jordan R C, McAdoo W G, Nezu A M 1988 Effects of four maintenance programs on the long-term management of obesity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 56(4): 529–34

- Stuart R B 1967 Behavioral control of overeating. Behavior Therapy 5: 357–65

- Wadden T A, Foster G D 2000 Behavioral treatment of obesity. Medical Clinics of North America 84(2): 441–62

- Wilson G T 1994 Behavioral treatment of obesity: Thirty years and counting. Advances in Behavioral Research Therapy 16: 31–75

- World Health Organization 1998 Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland