View sample men’s health research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a health research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Introduction

The realization that the health of men is an area that requires specific attention has only recently been recognized. Ten years ago, there was very little mention of male health issues other than perhaps a brief mention of prostate cancer or testicular cancer and, while it was known that perhaps more men died of coronary heart disease or accidents in their younger years than women, little else was seen to be of note. Even those working in the field of masculinity studies seemed to miss the relevance of health to men, with their focus on men and violence, men and sex, men and work, etc.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

There is now, however, an appreciation that men are much more at risk than first thought, with distinct inequalities existing between men and women and between men from differing cultural and socioeconomic circumstances. Premature death in men is seen across the disease spectrum and the way men deal with emotional problems results in high levels of addiction and suicide. These problems are compounded by a socialization process that sees men as not only revered as risk takers, but also inhibited from using health services in avoidance of being seen as weak.

Change is happening and across the world as a growing awareness of men’s health is creating new opportunities for policy makers, practitioners, academics, and the public recognize that not only is men’s health amenable to change, but there are now examples of good practice to draw on.

These issues are explored within this research paper. Data from recent international studies on the state of men’s health are used to outline the extent of the problems facing men. This is contextualized within a discussion on the impact of male socialization and the place of men’s health within the broader gender mainstreaming debate. This is followed by an account of activity around the world on what is being done to target policy and services more effectively.

Men As Part Of The Gender Debate

The issue of gender has been a key factor influencing the development of much of the policy development at the World Health Organization and in member states throughout the world. Since the Beijing Platform for Action at the 1995 UN International Conference for Women, mainstreaming gender equality was predominately seen as a commitment to ensure that women’s as well as men’s concerns and experiences became incorporated into all aspects of an organization, from employment issues through to organizational governance, delivery, and outcomes.

In recent times, it has been recognized that this drive for equality must also recognize the health issues that seem to have a more detrimental effect on men, such that all health policy must really be viewed through a lens that recognizes both men and women. There are wide implications for this, and they are being felt at all levels of policy production and implementation as attempts are made to disaggregate population-wide initiatives into policy that is sensitive to the needs of both genders. There is a benefit, however, as it is recognized that the tendency to create gender-blind policy has had the effect of serving neither men nor women effectively.

Definition Of Men’s Health

Early attempts to define men’s health tended to focus onto the biomedical challenges that beset men and did not pay sufficient attention to the broader social factors that also create problems for how men live healthy lives. The current definition offered by the Men’s Health Forum (England) gives perhaps the best indicator that the issue of men’s health has to be recognized at the broadest policy level, including social care policy, education policy, what is happening in the work environment, what is happening in transport, what is happening in the prison service, etc., as well as at the personal level.

A male health issue is one arising from physiological, psychological, social or environmental factors which have a specific impact on boys or men and/or where particular interventions are required for boys or men in order to achieve improvements in health and well-being at either the individual or the population level (Men’s Health Forum, 2004).

Men’s Health – Causes Of Concern

Life Expectancy

When asked, the majority of people will be aware that men have a shorter lifespan than women; it is such a well-known fact that it barely gets mentioned. But it is significant that of the 193 countries listed by the United Nations Statistics Division, in 184 of those countries men had a life expectancy shorter than women, with four countries having men living longer lives (with men living 2 years longer than women in Kenya and 1 year longer in the Maldives, Zimbabwe, and Zambia). The median difference between men and women is 5 years, but in Russia there is a 13-year gap.

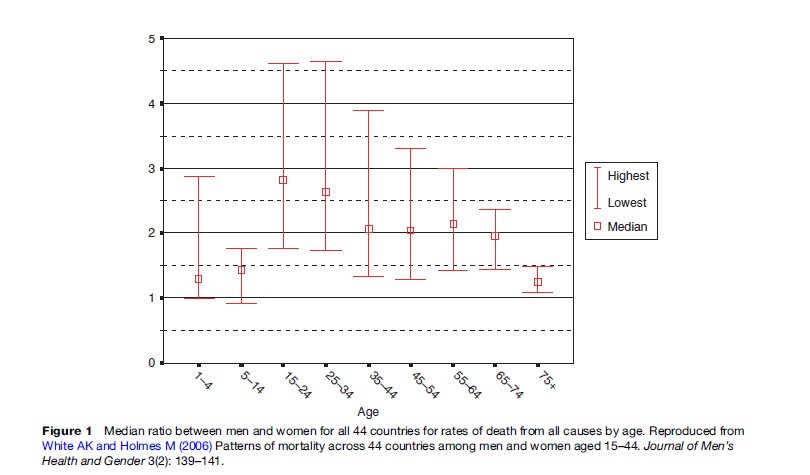

When the mortality data are further explored, it seems that men appear to die in greater numbers compared to women across the entire lifespan: From conception the male embryo is more likely to be spontaneously aborted, more male children die, more young men die, and more middle aged men die. Only after the age of the normal life expectancy of men is there a female excess of death. As part of a study exploring patterns of mortality in young men and women across 44 countries, the ratio of male deaths to female deaths was calculated (see Figure 1): it can be seen that the ratio of male deaths to female deaths is still higher even in this older age group.

It can be seen that the highest ratios of death in men compared to women occurred within the age range 15–24 (median ratio, 2.8) and 25–43 (median ratio, 2.6), with decreasing ratios with increasing age. Marked inter-country variations were found within Estonia and Latvia, which had over 4.5 times the rate in men as in women in the age groups 15–24 and 25–34; for Egypt, the Netherlands, and Hong Kong, male deaths are less than twice that of female deaths in these age groups.

Premature Death

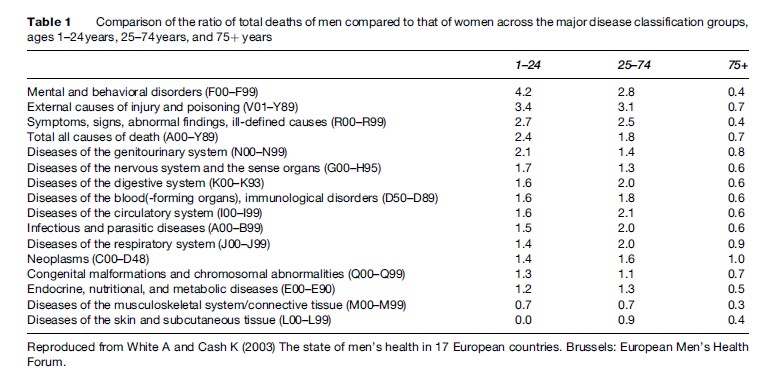

An epidemiological study by White and Cash (2004) examined the extent of premature death in Western European men and highlighted that a shorter life expectancy in males was not just a result of the expected causes, such as accidents and coronary heart disease, but rather that men were dying sooner from the majority of conditions that should have affected men and women equally (Table 1).

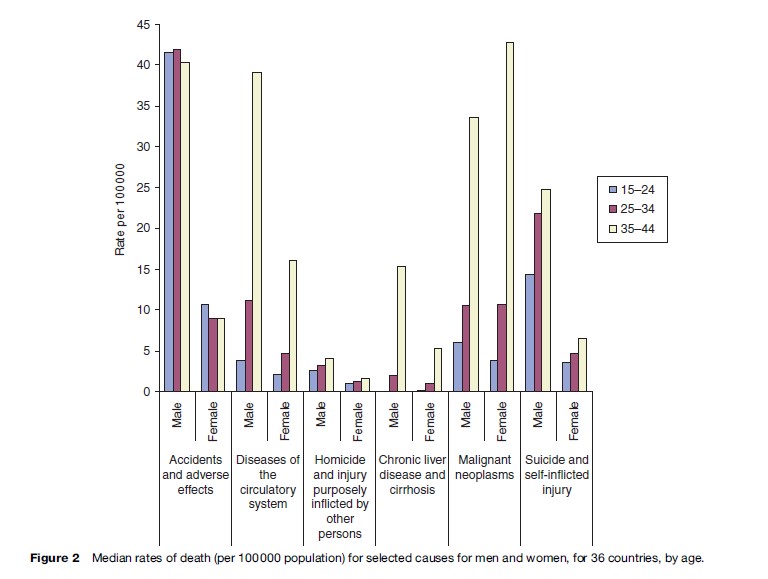

A more recent epidemiological study (White and Holmes, 2006) explored mortality patterns across 44 countries for both men and women aged 15–44 years. Within this study, which utilized data from the World Health Organization Mortality Database, patterns of mortality within the age band 15–44 years with six main causes of death were included in the analysis:

- accidents and adverse effects

- suicide and self-inflicted injury

- diseases of the cardiovascular system

- malignant neoplasms

- chronic liver disease and cirrhosis

- homicide and injury purposely inflicted by other persons

Across the majority of countries in the age ranges of 15–24 and 25–34 years, the highest rates of mortality were as a result of non-disease causes, including accidents, adverse effects, and suicide, with a three to fourfold increase observed in the 35–44 year age group in disease-related deaths, the suggestion again being that men’s risky lifestyles contribute to the early loss of life but also have an impact on the susceptibility of men to developing life-threatening illness. Homicide was not seen to be a major cause of death with the majority of countries (Brazil and, to a lesser extent, the US being notable exceptions); mortality attributable to homicide represents a very small proportion of deaths in these age ranges (see Figure 2).

To understand why men have this higher rate of death, it is necessary to explore the possible contributory factors that may make them more vulnerable.

Men And Their Biophysiology

There are implications for being biologically born a male, with the American Medical Association recognizing the following key differences between males and females:

- differences associated with the sex chromosomes

- differences in immune response

- differences in symptoms, type, and onset of cardiovascular disease

- differences in response to toxins

- differences in brain organization

- differences in pain perception (Wizemann and Pardue, 2001).

A bio-physiological difference that was not fully developed within Wizemann and Pardue’s text was the issue of obesity, which is becoming a global problem and has significant gender implications and will be discussed later.

The full implication of these differences has yet to be fully worked out, but the differences with regard to cardiovascular disease certainly create a gender divide, this being a problem of younger men and older women, which helps explain why so many more men are at risk of premature death from this cause. It is not possible, however, to explain all the other differences based on this information or even the full extent of the differences in the number of deaths from these differing causes from country to country.

It appears that many of the problems that men face can be traced back to their risky lifestyles, and much of this relates to the expectations of society regarding how men should live their lives and how men themselves are socialized into that role.

Factors Affecting Men’s Health

Impact Of Masculinity And Male Socialization

One of the principal factors influencing men’s health is how boys are prepared for adulthood, which can be argued is a significant factor of men’s problematic relationship with their health. From birth boys are treated differently from girls, if not by their parents then by friends, family, school teachers, and others they come in contact with. They are also influenced by television, films, books, and the marketing of boys’ and girls’ toys and clothing. The message is one of ‘big boys don’t cry’ and that boys are expected to be active with risk-taking behavior not only condoned, but actively encouraged.

In exhibiting or enacting hegemonic ideals with health behaviors, men reinforce strongly held cultural beliefs that men are more powerful and less vulnerable than women; that men’s bodies are structurally more efficient than and superior to women’s bodies; that asking for help and caring for one’s health are feminine; and that the most powerful men among men are those for whom health and safety are irrelevant (Courtenay, 2000).

Work that has been done with boys and young men at school to try to understand the pressures as they grow into manhood highlights that discussing their emotions, feelings, and relationship issues is frowned upon by boys and construed as being a female-orientated occupation. Being viewed as overly concerned with emotional issues results in peer group sanctions, such as bullying, name calling, chastising, and physical abuse, all employed to make boys recognize their wayward activity. This negative social pressure is also seen to act against boys and men who wish to lead any form of alternative lifestyle to the mainstream, with young gay men especially often experiencing anxiety and depression. Missing out on this formative time for developing a vocabulary and introspection about their feelings (an emotional literacy) may explain why men are thought to be at a higher risk of emotional difficulties in their adolescence and adult life, adding to their reluctance to seek health-care support.

Socioeconomic Factors

A recent report on the inequalities in health across Europe (Mackenbach, 2005) highlighted that men seem to be more vulnerable to the effects of worsening socioeconomic factors than women, with life expectancies of men falling at a faster rate in areas of marked social change. This is seen most strikingly in the Eastern European countries with Russian men having an average life expectancy in the fifties and the higher rates of premature death in men from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and Hungary.

The impact of socioeconomic factors impacts all aspects of health, with men from poorer backgrounds having worse mental and physical health; even within prosperous countries the effect can be seen, with life expectancy in the UK varying up to 15 years between areas of deprivation and prosperity.

A study of lung cancer in four countries (England and Wales, Canada, the U.S., and Poland), compared the smoking habits and chances of both developing and dying of lung cancer between the countries and on socioeconomic status ( Jha et al., 2006). They found a twofold difference between the highest and the lowest social strata in overall risks of dying among men aged 35–69 years, with over half of all deaths in the lower social groups in all the countries being directly attributable to smoking.

Ethnicity

Men from different ethnic groups can be seen to have their own particular health challenges, with, for instance, African Caribbean men having a threefold greater chance of developing prostate cancer and men from South Asia having a four to six fold greater chance of developing diabetes (U.K. Department of Health, 1999). There are also issues in relation to racism within countries: for instance, Royster and colleagues (2006) conducted an epidemiologic study that detailed the experiences of African American men, suggesting that they felt excluded from mainstream health-care services as a result of their race and economic status, highlighting the concern that different cross-sections of society may not be able to derive similar benefits from the same health-care system. There are additional burdens that men experience such as the majority of new migrants and asylum seekers being male, with their own difficulties in accessing health services within their new countries.

Men As Risk Takers

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2006) in its 2006 report focused on risk as the key to the prevention of the majority of noncommunicable diseases and identifies eight specific factors:

- tobacco

- alcohol

- low fruit and vegetable intake

- physical inactivity

- high blood pressure

- high cholesterol

- overweight and obesity

- raised blood sugar.

Tobacco, inappropriate diet, and physical inactivity explain at least 75–85% of new cases of coronary heart disease.

All of this can be seen as problematic for men, with men having higher rates of addiction to tobacco and alcohol and also being diagnosed with high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels. Men are now also less likely to be engaged in physically demanding work and their levels of activity are dropping with a corresponding increase in weight (see the section titled ‘Men and their weight’).

There is another set of risks that relate to physical risk taking that can result in violent death, with young men in particular the most vulnerable. Although it is often assumed that men are biologically driven to take risks and behave recklessly, evidence suggests that differences in the accidental death rates of men and women are mainly explained by social and cultural factors that encourage boys and men to adopt activities and behaviors that expose them to greater risks (Robertson, 2007).

Unhealthy environments encountered through work, with higher levels of occupational injury and death in men, also contribute to this higher level of risk men encounter. In the countries of the European Union, annually there are an estimated 3 947 552 accidents at work requiring more than 3 days absence as compared to 602 190 for women (Dupre´, 2001).

Within the Eastern European countries, many of the violent deaths are a result of accidental poisoning due to alcohol, but there are still a substantial number of deaths that result from homicide, road traffic accidents, and suicide.

Men’s Usage Of Health Services

A further area that has been identified as affecting men’s health is their use of health services. It is recognized that men do not access family doctors to the same extent as women – indeed they are not frequent attenders of the majority of services that are related to health – pharmacies are predominately accessed by women, and men are less likely to have regular dental checks and eye checks, and are less likely to access health screening.

In part, this can be linked to the lack of formalized health screening for men and also the fact that for many men their health remains very static, without the need to access health services for contraception or prenatal care. Men’s bodies are also relatively unchanging, with none of the hormonal or physical changes associated with monthly menstruation as experienced by women.

The problem with the delay in seeking help results is in the reduced treatment options available for the physician and the increased risk of unnecessary disability or premature death (White and Banks, 2004).

Specific Health Concerns For Men

Men And Cancer

Examination of the incidence rates of cancer and the age-specific mortality data tend to suggest that men have a higher risk of developing and prematurely dying of the cancers that should affect men and women equally (White and Cash, 2004; White and Holmes, 2006). The reason for this may be the increased rate of smoking, which leaves men open to the smoking-related cancers, for instance cancer of the lips, pharynx, cancer of the stomach, and cancer of the bladder. Male-type obesity, as seen in the section titled ‘Men and their weight,’ increases the risk of the fat-related cancers: cancer of the prostate, esophagus, etc. There may also be issues relating to delay in presentation with symptoms, which will reduce the treatment options.

Men And Their Cardiac Health

A steady and significant reduction in the number of deaths as a result of coronary heart disease has occurred, but this still remains the largest cause of male death in many countries and a significant problem in others. There are environmental and cultural factors associated with the development of cardiovascular disease with a north–south divide in Europe caused by the high-fat, high-red-meat, high-calorie diet coupled with a reduction in exercise and an increase in smoking in the north, increasing risk. This pattern is also seen within the Americas, whose influence is affecting traditional dietary habits across the world. Interestingly, Swedish men, who have adopted more of a Mediterranean diet and way of life, have seen their cardiac death rate drop significantly, and Finland, which legislated to reduce fat and calories in the production of food, has also seen its levels fall.

Men And Their Emotional Health

It has been known for some time that men are less likely to seek professional help to address and discuss their depressive symptoms than women, with Moller-Leimkuhler (2002) identifying this problem as being a discrepancy of need, both in recognizing men’s symptoms as requiring health advice and also in terms of the possible consequences of seeking help with the fear of loss of status, loss of control and autonomy, incompetence, dependence, and potential damage to identity. These are important points to make clear, as the majority of men who actually enter psychotherapy are often very willing to engage with the process. Therefore, it cannot be appropriately stated that men are unable to benefit from therapy; rather it is more a problem of getting them integrated into the services in the first place.

The issue of men being less likely to seek help regarding psychosocial problems is compounded by the possibility that for many men, the way in which their mental health difficulties emerge are different from those experienced by women. Brownhill and colleagues (2005) suggest that the current diagnosis of depression is based upon the female presentation of signs and symptoms and that for men their presentation is more covert, with men overcompensating for their loss of control, leading to overwork or violence or maladjusted behavior, either toward themselves or others. Understanding why this phenomenon occurs requires an exploration of how men are socialized as children and ultimately trained to deal with their mental well-being (White, 2006).

Men And Their Weight

The problem of being overweight has tended to be seen as a female issue; however, although more women than men are obese, there are more overweight men, with the numbers increasing rapidly (White and Pettifer, 2007). It is now estimated that 75% of British men will be overweight by 2010.

This rapid increase can be seen to be partially a result of significant changes in society, such as:

- changes in eating patterns

- increasingly sedentary lifestyle

- decline in manual labor

- reduction in walking

- reduced opportunity for exercise

- alcohol consumption

- long working hours.

The relevance of weight to men is that they tend to deposit fat intra-abdominally, leading to the apple shape of men as compared to the pear shape of women whose fat tends to be deposited in their hips and thighs. This visceral fat in men is problematic because it is not an inert substance but has its own endocrine function, with the creation of fat toxins that can lead to the fat-related cancers such as prostate, testis, bowel, liver, kidney, esophagus, and stomach. It also leads to a higher risk of developing hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes as a result of the metabolic syndrome. Erectile dysfunction, increased risk of dementia, and sleep apnea are also seen as a consequence of excess weight.

It is also compounded by men’s relationship with their weight and with food. The social pressure on boys is to be a big man, with the muscular body seen as the ideal. The effect of this is that normal-sized boys have been found to see themselves as underweight, as opposed to girls who, when a normal weight, see themselves as overweight due to their social conditioning. For instance, in a study of 813 men and women between the ages of 19 and 39, 28–68% of normal-weight boys felt they were underweight, while 30–67% of normal-weight girls felt they were fat (McCreary and Sadava, 2001), such that young women tend to diet to lose weight young, whereas men diet to put weight on.

Men And Their Sexual And Reproductive Health

The male reproductive system has the potential to create many problems for men throughout their lives. Congenital defects can affect the development of the penis and testes, leading to difficulties ranging from the results of disordered body image to the absence of secondary sexual development. The size and shape of the penis is a focus of most young boys’ fears as to whether they are normal, and although for girls the menarche is a sign of oncoming womanhood, the first ejaculation is a hidden and often embarrassing event that is certainly not a topic of conversation.

Testicular Cancer

Though testicular cancer is not very common, it can affect men at any age, is still the main cause of cancer-related death in young men, and is an increasingly common condition in some countries, with the incidence doubling in the UK over the past 20 years. Thankfully, this cancer has a very good cure rate. Since the discovery of the effects of platinum as part of the chemotherapy regimen, the chance of survival has increased to nearly 95%; however, this is based on an early diagnosis and there are still a significant number of men who delay seeking help and have a much poorer prognosis.

Prostate Problems

The prostate is the organ that produces the fluid that forms the ejaculate and with its location, encircling the urethra as it emerges from the bladder, is a major source of health problems for the aging male. With increasing life expectancy in men, it is now estimated that 43% of men have a lifetime risk of developing benign prostatic hyperplasia and a 9% chance of being diagnosed with prostate cancer. However, despite this now becoming one of the most common cancers in men across the developed world, it is still under-recognized, with many sufferers putting their symptoms down to increasing age rather than a treatable condition.

Erectile Dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) (or impotence) was once thought to be principally of psychogenic origin and while psychosexual problems are still a key factor for many men, current research has shown that disordered physiology is mainly to blame. Vascular disease is responsible for 70% of EDs, such that now ED is almost seen as the sentinel marker for cardiovascular disease.

Assessing a number of studies Solomon et al. (2003) found that:

- 15% of men with hypertension had complete ED (increasing to 20% in men who smoked)

- 39% of men with cardiac disease had complete ED (increasing to 56% in men who smoked)

- over 60% of men with ED had hypercholesterolemia

- between 39 and 64% of men with heart disease, myocardial infarction, or vascular disease also had ED.

Male Infertility

Infertility, defined as the inability of a couple of prime reproductive age (16–30 years) either to achieve pregnancy or to carry a pregnancy to live birth after 12 months of unprotected sex, is usually seen as a female problem. However, there is a female-only factor in 40% of infertile couples, a male-only factor in 30% of infertile couples, and female and male factors in 30% of infertile couples, such that it has to be seen as a gendered condition.

Sexually Transmitted Disease

Though HIV/AIDS can be spread via infected needles and blood products, it is predominantly transmitted through sexual contact and the numbers of men infected are increasing, as are the numbers of those infected with syphilis and gonorrhea. The gendered nature of HIV is recognized by the WHO and the UN, with women being specifically identified as being at increased risk of developing the disease from men during intercourse, with men’s reluctance to use condoms and to some men’s propensity to have multiple partners cited as principal factors; however, there are also significant problems for men as a result of this disease, with premature death, disability with reduced ability to work, and social stigma. Greater efforts are needed to engage specifically with men to improve their sexual health and also to influence their sexual risk taking.

Men And Violence

The majority of violent acts are carried out by men against men, with the possibility of men dying as a result of homicide far higher than for women. From the analysis of patterns of mortality in the 15–44 age band, the median death rate showed men’s deaths were over 2.5 times that of women’s deaths, with Brazil having 94.3 male deaths per 100 000 in the 15–24 age bracket as compared to 6.9 deaths per 100 000 for women (White and Holmes, 2006).

The World Health Organization Report on Violence (Krug et al., 2002: p. 98), however, recognizes that women are at a significant risk from men and list the following factors that contribute to a man’s likelihood of abusing his partner:

Individual factors

- young age

- heavy drinking

- depression

- personality disorders

- low academic achievement

- low income

- witnessing or experiencing violence as a child.

Relationship factors

- marital conflict

- marital instability

- male dominance in the family

- economic stress

- poor family functioning.

Community factors

- weak community sanctions against domestic violence

- poverty

- low social capital.

Societal factors

- traditional gender norms

- social norms supportive of violence.

These suggest that a man is himself subject to the influence of many powerful factors, including depression, personality disorders, alcohol abuse, poverty, marital conflict – all recognized as being under-recognized and under resourced in terms of providing targeted support for men. The implication is that better support for men will have a positive effect on women as well.

Activity In Men’s Health

With the problems men face with their health spanning a broad range of issues, it is important that the complexity of the task in getting men’s health improved cannot be overstated. We are seeing a combination of biological, social, environmental, and cultural factors affecting how men are both prepared for managing (or not) their own health and also the world in which they live. Economic expectations of men to be the main wage earner, often in difficult and dangerous circumstances, coupled with a socially prescribed expectation that the man will not own up to vulnerabilities makes for a dangerous cocktail that results in many men suffering disability or premature death.

Activity Guiding Development Of Men’s Health

As already mentioned, the current wave of interest in men’s health fits with the push by the WHO for gender mainstreaming, with other cross-national organizations also picking up the challenge. The European Commission recognizes that there is a need for gender to be a part of all funded research programs (European Commission, 2001) and is exploring the implications of the gender equity policy development on men’s health. But aside from this high-level policy work, there is a substantial degree of other international activity currently ongoing.

Every year the International Men’s Health Week, which runs in the week up to Father’s Day in June, takes a new focus attention. In 2004, the theme was men and cancer, in 2005 men and their weight, and in 2006 men and their emotional well-being.

We now have the International Society of Men’s Health and the European Men’s Health Forum, and at the 4th World Congress on Men’s Health the Vienna Declaration on Men’s Health was launched.

We are now also seeing an increase in the number of international journals, with the Journal of Men’s Health and Gender serving more of a medical audience and the International Journal of Men’s Health having more of a social science focus. The American Journal of Men’s Health, launched in 2007 is another recent significant journal.

At a national level, there are varying amounts of activity, with many countries now having some form of formalized organization aimed at developing men’s health. Many countries now have national organizations that are focused on men’s health issues, for instance the Men’s Health Network, The Australian Men’s Health Information and Resource Centre, and the Men’s Health Forum (MHF) in England, with similar MHFs now found in Scotland, Ireland, Wales, the Philippines, and Hong Kong. Australia, the U.S., and Ireland are all working on a National Men’s Health Policy, and the Men’s Health Forum in England has become very influential in its work, with key policy documents being produced (for instance, ‘Men and Cancer’ in 2004 and ‘Men and Emotional Wellbeing’ in 2006 and their major policy document ‘Getting It Sorted’) and have coordinated the production of a successful series of books for men, published by Haynes (Banks, 2002).

The new Scottish Assembly have recently funded (£4 million) a series of pilot community-based men’s health initiatives with the intention of building on the success of the Camelon Centre for Men’s Health. This appears to be the biggest investment yet by a government into the health of men worldwide.

There are organizations that have directed their activity specifically focused on men, including the work of the Institutio Promundo, an NGO working from its base in Brazil, on the socialization of young men in the field of gender equality, violence prevention, and HIV/AIDS (Barker, 2005).

Conclusion

There has been a large amount of activity related to men’s health over the last 10 years and it seems that as awareness grows this rate of growth will continue. With the push for gender equity and gender mainstreaming, there will increasingly be a political imperative to see activity within the field of men’s health continue to enable some of the marked inequalities that exist between men and women and between men of differing social and ethnic backgrounds to be addressed.

A further issue is that the risks men take with their health go far beyond affecting their own personal safety; they impact women, their families, their work, and ultimately the whole fabric of society. For a public health agenda to be effective, there is a requirement for the problem to be understood from the man’s perspective.

If there is not an investment in exploring the health beliefs and behavior of men and boys and the factors that influence their development, then we will continue to see men as feckless as opposed to a victim and progress will not be made.

Bibliography:

- Banks I (2002) The Man Manual. Sparkford, UK: JH Haynes.

- Barker GT (2005) Dying to Be Men: Youth, Masculinity and Social Exclusion. Adingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Brownhill S, Wilhelm K, Barclay L, and Schmied V (2005) ‘Big build’: Hidden depression in men. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 39: 921–931.

- Courtenay WH (2000) Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science and Medicine 50(10): 1385–1401.

- Department of Health (1999) The Health of Minority Ethnic Groups: Health Survey for England. London: Department of Health.

- Dupre´ D (2001) Accidents at Work in the EU 1998–1999; Statistics in Focus 16/2000. Brussels, Belgium: Eurostat.

- European Commission (2001) Gender in Research: Gender Impact Assessment of the Specific Programmes of the Fifth Framework Programme: An Overview. Brussels, Belgium: The European Commission.

- Jha P, Peto R, Zatonski W, Boreham J, Jarvis MJ, and Lopez AD (2006) Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: Indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. The Lancet 368(9533): 367–370.

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, et al. (2002) The World Report on Violence and Health 2002. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Mackenbach JP (2005) Health Inequalities: Europe in Profile. Erasmus MC: University Medical Center Rotterdam. Available at: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/media/health_inequalities_europe.pdf

- McCreary DR and Sadava SW (2001) Gender differences in relationships among perceived attractiveness, life satisfaction, and health in adults as a function of body mass index and perceived weight. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 2: 108–116.

- MHF (2004) Getting it sorted: A Policy Programme for Men’s Health. London: The Men’s Health Forum.

- Moller-Leimkuhler AM (2002) Barriers to help seeking by men: A review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 71: 1–9.

- Robertson S (2007) Understanding Men and Health: Masculinities, Identity and Well-being. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press, McGraw Hill Education.

- Royster M, Richmond A, Eng E, and Margolis L (2006) Hey brother, how’s your health? A focus group analysis of the health and health-related concerns of African American men in a Southern City in the United States. Men and Masculinities 8(4): 389–390.

- Solomon H, Man J, and Jackson G (2003) Erectile dysfunction and the cardiovascular patient: Endothelial dysfunction is the common denominator. Heart 89: 251–254.

- White AK (2006) Men and Mental wellbeing: Encouraging gender sensitivity. Personal Perspective, Mental Health Review Journal 11(4): 3–6.

- White AK and Banks I (2004) Help seeking in men and the problems of late diagnosis. In: Kirby RS, Riad N, and Farah M (eds.) Men’s Health, 2nd edn. London: Martin Dunitz.

- White AK and Cash K (2004) The state of men’s health in Western Europe. Journal of Men’s Health and Gender 1(1): 60–66.

- White AK and Holmes M (2006) Patterns of mortality across 44 countries among men and women aged 15–44. Journal of Men’s Health and Gender 3(2): 139–141.

- White AK and Pettifer M (2007) Hazardous Waist: Tackling Overweight and Obesity in Men. Oxford, UK: Oxford Radcliffe Publishing.

- Wizemann TM and Pardue ML (2001) Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine.

- World Health Organization (2006) Risk Factors: Integrated Approach to Reducing Risk. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.