Sample Health Education And Health Promotion Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Health education is any combination of learning experiences designed to facilitate voluntary actions conducive to health (Green and Kreuter 1999). Health promotion is the combination of educational and environmental supports for actions and conditions of living conducive to health (Green and Kreuter 1999), thereby including health education. The two definitions represent a historical development in approach from more individual to more ecological where the role of the environment has acquired increased relevance in understanding and changing conditions for health. For this reason, we will use the term health promotion in the remainder of this research paper. Health promotion can be characterized by four other main developments: the need for planning, the importance of evaluation, the use of social and behavioral science theories, and the systematic application of evidence and theories in the development of health promotion interventions. Finally, we will describe recent developments in information technology (IT) and their effect on health promotion.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Health, Environment, And Behavior

In the ecological approach to health promotion, health is viewed as a function of individuals and the environments in which individuals are embedded, including family, social networks, organizations, and community and public policies. The relation between social economic status and health is a clear example of environmental influences on health. At the same time it also constitutes a major challenge. The central concern of health promotion is health behavior. However, health behavior refers not only to the individual’s behavior but also to the behavior or actions of groups and organizations. Stress at work may be related to individual coping behavior, but also to managers’ decision-making behavior (organization). Richard et al. (1996) describe the various environmental levels as embedded systems. They indicate that individuals exist within groups, which are in turn embedded within organizations and higher order systems. The individual is influenced by, and can influence directly or through groups and organizations, the higher order systems. The picture that emerges is a complex web of causation as well as a rich context for interventions. In the stress example, the individual as well as the manager will both be targets for health promotion interventions. Moreover, at the society level, the intervention may target politicians’ decision-making related to a healthier organization of labor. We see managers and politicians as agents in the environment who serve as targets for health promotion interventions (Bartholomew et al. 2000).

2. Health Promotion Planning

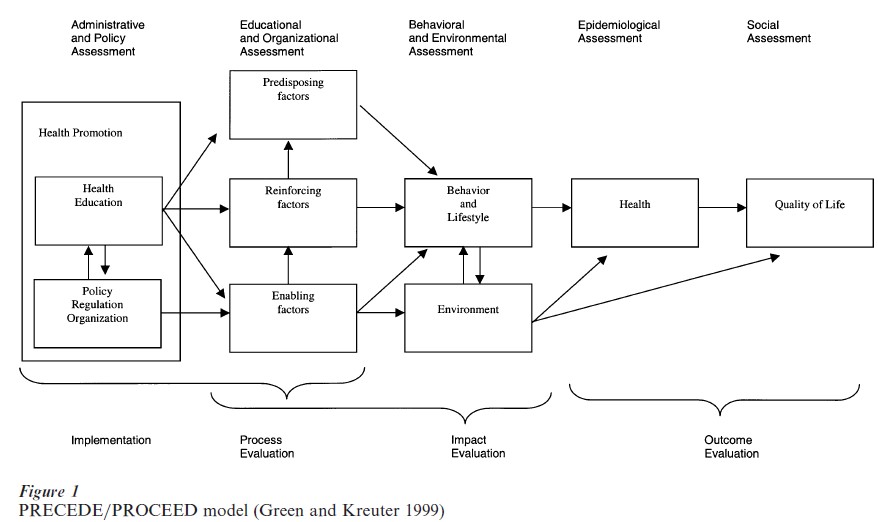

Health promotion is a planned activity. The most widely used health promotion planning framework is Green and Kreuter’s (1999) PRECEDE PROCEED model (see Fig. 1).

The model begins on the right with the assessment of quality of life and health problems, changes in which should be the proposed outcomes of a health promotion intervention. It then guides the planner to assess the behavioral and environmental causes. In the behavioral assessment typically one asks what the individuals at risk are doing that increases their risk of death from the health problem. In the environmental assessment we ask what factors in the environment are related to the health problem directly or to its behavioral causes. In the previous subsection, it was explained how the environmental causes can be viewed as behaviors or actions at various environmental levels: groups, organizations, communities, and society.

In the next phase of PRECEDE/PROCEED, the determinants of the behavioral and environmental factors are assessed. Green and Kreuter (1999) describe determinants affecting behavior as predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling. Predisposing factors relate to the motivation of an individual or a group to act. Notice that the target may also be an agent in one of the environmental levels, such as a manager or a politician. These factors mostly fall into the psychological domain and include the cognitive and affective dimensions of knowing, feeling, believing, valuing. Reinforcing factors are those consequences of action that determine whether the actor receives positive (or negative) feedback and is supported socially after it occurs. Reinforcing factors thus include social support, peer influences, and advice and feedback by healthcare providers. Notice that the perception of social support would be a predisposing factor. Reinforcing factors also include physical consequences of the behavior such as well-being or pain. Enabling factors, often conditions of the environment, facilitate the performance of an action by individuals, groups, or organizations. Factors included are the availability, accessibility, and affordability of healthcare and community resources. Enabling factors also include new skills that a person, organization, or community needs to learn to carry out a behavioral or environmental change. Notice that self-efficacy expectations are a predisposing factor, the actual skills an enabling factor.

PRECEDE/PROCEED suggests that program planners start with the assessment of quality of life and health problems. In practice, that is a rare situation. Often health educators start somewhere within the model, depending on their task description or the specific moment in the ongoing health promotion planning process. For example, a health educator may be hired to develop a smoking prevention program for schools. We then enter the model at the behavior box. However, we first want to go back, to the right, and (re-)assess the quality of life and health problems as well as the behavioral and environmental conditions before we go on to the assessment of determinants of the behavior and environmental conditions and the development of the program.

The next phases of PRECEDE/PROCEED involve the administrative and policy assessment. The planner will now develop the plans into health education and other health promotion interventions, such as policy, regulation, or organization. The assessments include identifying barriers to overcome in implementing the program and policies that that can be used to support the program. We then proceed to program implementation. Implementation is an essential element in the planning process. Without implementation, the intervention will not have any impact on determinants, behaviors, or health. The final phases of PRECEDE/PROCEED describe the evaluation levels: process, impact, and outcome. Thinking about implementation and evaluation has to start as early as possible, not after the intervention development. In the Intervention Mapping protocol, anticipating implementation and evaluation are steps in the development process.

3. Program Evaluation

Even the best planned health promotion intervention may not have much effect. It is important to always evaluate the effect of an intervention, its impact and process. When the program has failed, we need to know why it failed. Rossi et al. (1999) suggest four levels of evaluation:

(a) Program conceptualization and design refers to the planning process and the use of theory and evidence in the development of the program.

(b) Program monitoring provides feedback on the actual implementation of the program and its reception by the target population.

(c) Impact evaluation is defined by Rossi et al. as the extent to which a program causes change in the desired direction. They use the word impact to make clear that the desired effect of a program may be defined at different levels, and often not at the health and quality of life level. It is useful to agree on the operationalizations of desired effects before the actual implementation of the program.

(d) Program efficiency evaluates the program in terms of costs and effects, such as cost-benefits and cost-effectiveness analyses.

Rossi et al. are very outspoken on when to evaluate and when not to evaluate: ‘Clearly, it would be a waste of time, effort and resources to estimate the impact of a program that lacks measurable goals or that has not been properly implemented.’

Effect evaluation relies heavily on quasi-experimental designs (Rossi et al. 1999). The basic principle in effect evaluation is the random assignment of participants to the program group and a control group. Only then can we give a straightforward answer to the question if an intervention was successful. In health education practice the random assignment of individuals is often impossible. For instance, students from secondary schools cannot be assigned randomly to a school program or a control program, because most school programs are school-wide or at least class-wide. In that case, we ask various schools if they are willing to participate in the program, and we then assign schools randomly to the program condition or the control condition. A variety of quasi-experimental designs allow us to compare two or more groups that are as similar as possible. We have to expect that the groups are not completely equivalent on a number of relevant characteristics, and we cannot even assume that we know all the relevant characteristics. Statistically, we can control for most of these differences and levels, but only when we measure them before the program starts (see Bartholomew et al. 2000).

4. Social And Behavioral Science Theories

A health promotion program is most likely to benefit participants and the community when it is guided by social and behavioral science theories of health behavior and health behavior change (Glanz et al. 1997). Theory-driven health promotion programs require an understanding of the components of the theory as well as the operational or practical forms of these theories. Finding and applying relevant theories is a professional skill that health educators have to master (Bartholomew et al. 2000).

Notice that we assume that all theories are potentially applicable to all levels and also to adoption and implementation. The Theory of Planned Behavior, for example, is often applied to individual health behavior (Godin and Kok 1996) but also to politicians’ behavior (Flynn et al. 1998) and to implementers’ behavior (Paulussen et al. 1995).

The behavioral science theories that try to explain behavior and behavior change have two types of roots: health and health promotion in particular or behavior and behavior change in general (the last mainly being social psychological theories). Health and health promotion oriented theories are often related to perceptions of health risks, for example, the Health Belief Model (Sheeran and Abraham 1996, Strecher and Rosenstock 1997) or Protection Motivation Theory (Boer and Seydel 1996). Some other theories were developed in a health setting, but have evolved into a general theory such as the Transtheoretical Model of Stages of Change (Prochaska et al. 1997) or Relapse Prevention Theory (Marlatt and Gordon 1985). Most general social psychological models were developed for a broad range of behaviors, but are easily applicable to health behavior and change. Some examples are Learning Theories (Westen 1996), Information Processing Theory (Hamilton and Ghatala 1994), Theory of Planned Behavior (Connor and Sparks 1996, Montano et al. 1997), Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura 1997), Goal Setting (Strecher et al. 1995), Attribution Theory (Weiner 1986), Self-regulatory theories (Clark and Zimmerman 1990), Social Networks and Social Support theories (Heaney and Israel 1997), Persuasive-communication Model (McGuire 1985), and Diffusion of Innovations Theory (Rogers 1995).

At the organizational level, health educators draw from various Organizational Change theories (Goodman et al. 1997). Typically we use constructs from these theories for considering policy development within organizations and for promoting program adoption and implementation.

At the community and society level, theoretical input can be found in the classic models of community organization and community development and the current perspectives being used for health promotion (Minkler 1997). Issues of power, participation, and goals, for instance, have received much discussion among health educators in recent years. In selecting the constructs to use for community change, planners must clarify their assumptions and values about the nature of the change process and select and implement strategies congruent with these. Finally, there are theories of policy making that have been used primarily at the national, state, and governmental level, such as Policy Window Theory (Kingdon 1995).

Theories are very important tools for professionals in health education and promotion. On the one hand, theories have become available to health promotion practice through textbooks such as Glanz et al. (1997) or Connor and Norman (1996). On the other, the application of theory has long been a challenge, for researchers as well as practitioners. Students of health promotion learn of theories and learn how to apply theories to well-selected practical problems. However, in real life the order is reversed: the problem is given and the practitioner has to find theories that may be helpful for better understanding or changing behavior (Kok et al. 1996). Recently, a protocol was published that describes a process for developing theory-based and evidence-based health education programs: Intervention Mapping (Bartholomew et al. 2000).

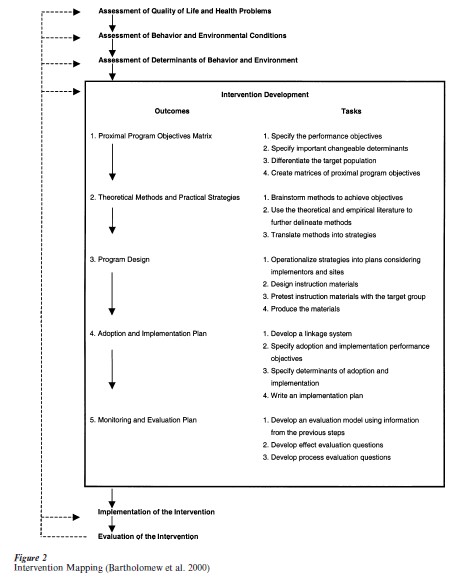

5. Intervention Mapping

Intervention Mapping distinguishes five steps: define proximal program objectives, select theoretical methods and practical strategies, design the program, anticipate adoption and implementation, and anticipate process and effect evaluation (see Fig. 2). Bartholomew et al. (2000) see planning as an iterative process: two steps forward and one step back. Bartholomew et al. (2000) describe three core processes for Intervention Mapping, tools for the professional health promoter: searching the literature for empirical findings, accessing and using theory, and collecting and using new data. From the literature search, a provisional list of answers is developed, which is often not adequate in finding solutions for the problem. The planner must go further to search for theory, using three approaches: issue, concept, and general theories approach. The issue approach searches the literature for theoretical perspectives on the issue. The concept approach begins with the concepts in the provisional answers, linking these concepts to theoretical constructs and theories that may be useful. The general theory approach considers general theories that may be applicable. Finally, it is important to identify gaps in the information obtained and collect new data to fill these gaps.

The first step in Intervention Mapping is the development of proximal program objectives, a crossing of performance objectives, determinants, and target groups. For instance, one proximal program objective for an HIV-prevention program in schools would be: ‘adolescents (target population) express their confidence (determinant) in successfully negotiating with the partner about condom use (performance objective).’ Performance objectives are the specific behaviors that we want the target group (or the environmental agents) to ‘do’ as a result of the program. For example, in the case of HIV prevention: buy condoms, have them with you, negotiate with the partner, use them correctly, and keep using them (Bartholomew et al. 2000). Determinants of behavior can be personal or external. Personal determinants are, for instance, outcome expectations, social influences, and self-efficacy expectations. External determinants are, for instance, social norms and support, and barriers. Target groups can be subgroups of the total group, for instance, men women, people in different stages of change. Proximal program objectives are numerous and should be ordered by determinant. So we end this step with a series of lists, for instance, all proximal program objectives which have to do with skills training.

Intervention Mapping Step 2 is the selection of theoretical methods and practical strategies. The theoretical method is the technique derived from theory and research to realize the proximal program objective; the strategy is the practical application of that method. For instance, the method for self-efficacy improvement could be modeling and the strategy could be peer modeling by video. An important task in this step is to identify the conditions or parameters that limit the effectiveness of theoretical models, such as identification, observability, and reinforcement as necessary conditions for the effectiveness of learning by modeling.

Intervention Mapping Step 3 is the actual designing of the program, organizing the strategies into a deliverable program, and producing and pretesting the materials. In the example of HIV-prevention in schools, the program comprised five lessons, an interactive video, a brochure for students, and a workbook for teachers (Bartholomew et al. 2000).

A solid diffusion process is vital to ensure program success. So, in Intervention Mapping Step 4, a plan is developed for systematic implementation of the program. The first thing to do, actually at the start of intervention development, is the development of a linkage system, linking program developers with program users. Then, an intervention is developed to promote adoption and implementation of the program by the intended program users. It may be clear that the anticipation of implementation is a relevant process from the very beginning of planning, not only at the end.

Finally, Intervention Mapping Step 5 focuses on process and effect evaluation. Again, this process is relevant from the start, not only at the end. For instance, ‘adolescents express their confidence in successfully negotiating with the partner about condom use’ is an objective, but is also a measure of that objective, that can be asked in pre- and postinterviews with experimental and control group subjects.

6. Recent Developments In IT

Mass media health promotion is able to reach large numbers of people, but a major weakness of mass media programs is their limited effect in terms of impact and outcome. However, more effective individualized health promotion is costly and time-consuming. Computer technology may help break several important barriers in health promotion related to individualization and program delivery. During the 1990s, health promotion researchers have been testing simple computer expert systems that enable the tailoring of communications to match certain characteristics that have been measured in individuals in the target group (Velicer et al. 1993, Brug et al. 1998, Dijkstra and De Vries 1999).

Velicer et al. define an expert system as a collection of facts and rules about something and a way of making inferences from the facts and the rules. The most common types of expert systems in health education are computer programs that are tailored to specific characteristics of the receiver. Thus, the expert system comprises one or more databases of messages based on theoretical constructs that vary as they apply to different characteristics of individuals, and on algorithms for matching the messages to individuals. The message channel could in general be anything that facilitates delivery of the message to the target: a report, a letter, computer-assisted instruction or any other channel. In the work of Velicer et al. (1993), messages were based on the Transtheoretical Model of Stages of Change and included processes of change tailored to the stage of the individual in regard to quitting smoking. Feedback included current status and stage of change, current use of change processes, suggested strategies, and high-risk situations. Feedback was compared against a normative database as well as against participants’ progress. All examples of computer-tailored health promotion in the literature are based on a similar configuration comprising (Brug et al. 1998):

(a) A theoretical framework and specification of relevant hypothesized determinants of the health behavior.

(b) Use of the determinant model to create a data collection tool and a series of messages that are tailored to these determinants.

(c) Several databases including, at least, a determinants file and a delivery message file.

(d) A set of decision rules and a tailoring program that executes these decisions.

(e) The actual communication messages.

(f ) Delivery vehicles, such as a printed letter.

It is to be expected that computer tailoring will become more popular in the future and will also be applied using the Internet.

7. Conclusion

Health education and health promotion are planned activities. PRECEDE/PROCEED provides a very useful framework for the systematic planning of health promotion and Intervention Mapping provides a very useful protocol for evidence-based intervention development. Both models acknowledge the role of the individual as well as the relevant ecological levels in the environment.

Bibliography:

- Bandura A 1997 Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Freeman, New York

- Bartholomew L K, Parcel G, Kok G, Gottlieb N 2000 Intervention Mapping; Designing Theory and Evidence-based

- Health Promotion Programs. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA Boer H, Seydel E R 1996 Protection motivation theory. In: Conner M, Norman P (eds.) Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognitive Models. Open University Press, Buckingham, UK

- Brug J, Glanz K, Van Assema P, Kok G, Van Breukelen G P 1998 The impact of computer-tailored feedback and iterative feedback on fat, fruit, and vegetable intake. Health Education and Behavior 25: 517–31

- Clark N M, Zimmerman B J 1990 A social cognitive view of self-regulated learning about health. Health Education Research 3: 371–9

- Connor M, Norman P (eds.) 1996 Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models. Open University Press, Buckingham, UK

- Connor M, Sparks P 1996 The theory of planned behavior and health behaviors. In: Connor M, Norman P (eds.) Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognitive Models. Open University Press, Buckingham, UK, pp. 121–62

- Dijkstra A, De Vries H 1999 The development of computer- generated tailored interventions. Patient Education and Counseling 36: 193–203

- Flynn B S, Goldstein A O, Solomon L J, Bauman K E, Gottlieb N H, Cohen J E, Munger M C, Dana G S 1998 Predictors of state legislators’ intentions to vote for cigarette tax increases. Prevention Medicine 2: 157–65

- Glanz K, Lewis F M, Rimer B K 1997 Health Behaviour and Health Education: Theory Research and Practice, 2nd edn. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA

- Godin G, Kok G 1996 The theory of planned behavior: A review of its applications to health related problems. American Journal of Health Promotion 11: 87–98

- Goodman R M, Steckler A, Kegler M C 1997 Mobilizing organizations for health enhancement: Theories of organizational change. In: Glanz K, Lewis F M, Rimer B K (eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 2nd edn. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 287–312

- Green L W, Kreuter M W 1999 Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach, 3rd edn. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA

- Hamilton R, Ghatala E 1994 Learning and Instruction. McGraw Hill, New York

- Heaney C A, Israel A 1997 Social networks and social support. In: Glanz K, Lewis F M, Rimer B K (eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 2nd edn. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 179–205

- Kingdon J 1995 Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies, 2nd edn. Harper-Collins, New York

- Kok G, Schaalma H, De Vries H, Parcel G, Paulussen T H 1996 Social psychology and health education. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M (eds.) European Review of Social Psychology. Wiley, Chichester, UK, Vol. 7, pp. 241–82

- Marlatt G A, Gordon J R 1985 Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviours. Guilford Press, New York

- McGuire W J 1985 Attitudes and attitude change. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E (eds.) The Handbook of Social Psychology, Vol. 2. Random House, New York, pp. 233–346

- Minkler M (ed.) 1997 Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, pp. 244–58

- Montano D E, Kasprzyk D, Taplin S H 1997 The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. In: Glanz K, Lewis F M, Rimer B K (eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 2nd edn. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 85–112

- Paulussen T, Kok G, Schaalma H P, Parcel G S 1995 Diffusion of AIDS curricula among Dutch secondary school teachers. Health Education Quarterly 22: 227–43

- Prochaska J O, Redding C A, Evers K E 1997 The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Lewis F M, Rimer B K (eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 2nd edn. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 60–84

- Richard L, Potvin L, Kishchuk N, Prlic H, Green L W 1996 Assessment of the integration of the ecological approach in health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion 10: 270–81

- Rogers E M 1995 Diffusion of Innovations, 4th edn. Free Press, New York

- Rossi P H, Freeman H E, Lipsey M W 1999 E aluation: A Systematic Approach, 6th edn. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

- Sheeran P, Abraham C 1996 The health belief model. In: Connor M, Norman P (eds.) Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models. Open University Press, Buckingham, UK, pp. 23–61

- Strecher V J, Rosenstock I M 1997 The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Lewis F M, Rimer B K (eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 41–59

- Strecher V J, Seijts G H, Kok G, Latham G P, Glasgow R, DeVellis B, Meertens, R M, Bulger D W 1995 Goal setting as a strategy for health behavior change. Health Education Quarterly 22: 190–200

- Velicer W F, Prochaska J O, Bellis J B, DiClemente C C, Rossi J S, Fava J L, Steiger J H 1993 An expert system intervention for smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors 18: 269–90

- Weiner B 1986 An Attributional Theory of Motivation and Emotion. Springer, New York

- Westen D 1996 Psychology: Mind, Brain, and Culture. Wiley, New York