View sample prison health research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a health research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Introduction

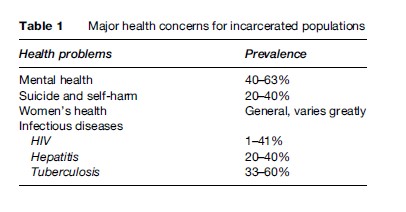

Prisons are among the most unhealthy environments in our societies. The levels of illness and health problems among prison populations tend to be much higher than in the general population. In prisons people are not only deprived of their freedom. They are also often exposed to special health risks, and at the same time their own capacity to manage these risks is severely constrained. Ensuring that prisoners have a standard of health care that is equivalent to that available in the community is a human rights obligation for states. It also is an integral part of any strategy for reducing health threats for the wider society, because any diseases contracted in prison or any medical conditions developed as a consequence of or made worse by poor conditions of confinement become issues of public health when prisoners are released. Of special concern in this context are mental health, suicide and self-harm, women’s health, and infectious diseases – the last concern having been chosen as a ‘case’ to be further examined in this research paper (see Table 1).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Research on health in prison has been undertaken for the last 20 years. It has tended to focus on prevalence and risk behavior in prisons, psychiatric care under conditions of security, transmission of infectious diseases, and preventive measures as well as aftercare, treatment, and support. With few exceptions, research studies have come from the field of medical sciences or public health. Societal and environmental determinants of health are, however, increasingly recognized as major factors in keeping people healthy. If one takes a closer look at the key risk factors that contribute to poor health conditions in prisons, one finds that many are rooted in poor prison conditions, overcrowding, and the socioeconomic background of prison populations. The majority of studies on tuberculosis in prisons, for example, highlight overcrowding as a key factor promoting the spread of the disease, and many studies on HIV in prisons stress the sentencing policies for drug users and the risk behavior of prisoners as two of the main obstacles for successful prevention interventions. This research paper therefore focuses on the wider prison and penal policy issues that play a role in improving prisoners’ health.

Mental Health

Serious personality disorders, drug and alcohol dependence, suicidal and self-harming behavior, and psychotic or neurotic mental illness are widespread in prisons, with female prisoners disproportionately affected. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that, on average, 40% of all prisoners suffer from a mental disorder; the inclusion of substance abusers can raise this rate to 63%. This high rate of mental health problems is especially related to the lack of, or poor access to, community mental health services in many countries. Many people with mental illness, particularly those who are poor, homeless, or struggling with substance abuse problems, cannot obtain mental health treatment in the community and are swept into the criminal justice system after they commit a crime. The emphasis on deterrence and punishment rather than treatment and care can leave prison as the only option for mentally ill people. In many countries, the surging number of mentally ill men and women entering the prison system has therefore outrun the availability of services in prisons.

Mental disorders may also develop during the period of imprisonment as a consequence of prevailing conditions and, in many countries of the world, because of torture or other human rights violations. Mentally ill prisoners can find it difficult if not impossible to comply with prison rules, and security staff members often do not distinguish between the prisoner who is disruptive or fails to obey an order because of illness and a prisoner who causes problems for other reasons. As a result, mentally ill prisoners are often neglected, accused of malingering, or treated as disciplinary problems. They thus end up with higher than average rates of disciplinary infractions and can accumulate extensive disciplinary histories, which makes them more likely than other prisoners to be housed in especially harsh conditions, such as isolation, that can push them into acute psychosis.

Suicide And Self-Harm

One important manifestation of the cumulative effects of imprisonment is the fact that in many countries suicide is the single most common cause of death in custody, according to the WHO. The psychological impact of arrest and incarceration or the day-to-day stresses associated with prison life may exceed the coping skills of vulnerable individuals. Although comparative suicide rates are difficult to obtain, some research estimates that, internationally, one in five men in prison and nearly 40% of women have attempted suicide at some time during their imprisonment and that prisoners are up to seven times more likely to commit suicide than people in the community. In pretrial facilities the suicide rate is ten times that of the outside community. In addition, for every actual suicide, there are many more suicide attempts.

A key strategy in reducing the number of prison suicides and other forms of self-harm is integrated and effective prisoner management. This approach includes identifying and then paying greater attention to prisoners identified as at risk, making effective use of observation cells, and implementing mental health treatment and staff training. However, many prisons lack formal policies and procedures to identify and manage suicidal prisoners. Even if appropriate policies and procedures exist, overworked or undertrained prison personnel may miss the early warning signs of potential suicide attempts. In many prisons, access to mental health professionals is complicated by the limited internal mental health resources and few, if any, links to community-based mental health facilities.

Women’s Health

Most prison systems are designed with male prisoners in mind, which explains why living conditions for women prisoners are often not tailored to their specific needs. The health services provided for women are sometimes minimal or inferior, and referral to outside facilities is also often more difficult than for male prisoners. Basic requirements such as greater access to showers or the availability of hygiene products are often not provided. Not all women’s prisons cater adequately for women who are pregnant or for mothers with newborn babies or young children. Additionally, many imprisoned women have experienced physical and sexual abuse and have lacked previous health care in their communities, two factors that put them at greater risk for having high-risk pregnancies and for developing life-threatening illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C, and cervical cancer. Moreover, in many prisons throughout the world, women are victims of sexual abuse by prison staff and male prisoners and at times during routine medical examinations. Sexual abuse is especially prevalent when a state fails to provide separate accommodations for women deprived of their liberty, where female staff outnumber their male colleagues.

Infectious Diseases

One of the biggest challenges for penitentiary systems worldwide is the transmission of infectious diseases in prisons, which has a direct and measurable impact not only on the prison environment itself but also on the wider community in which prisons operate. Within the context of public health research, the issue of disease transmission in prisons is therefore especially relevant and is the main focus of this research paper. The key medical and policy issues raised by the linked resurgence of communicable and sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV/ AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), and hepatitis are representative for most other health problems in prisons. Infectious diseases are therefore examined in this research paper to highlight policy directions and alliances that can be effective in improving the health of prisoners. The same principles can be applied to a large number of other health problems in prisons.

Prevalence Of Infectious Diseases In Prisons

The risk of disease transmission in prison settings is well recognized and documented. Although it is difficult to estimate the precise number of infections among prisoners, imprisonment – and the amount of time spent in prison – has been identified as a major independent risk factor for the transmission of infections like HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and hepatitis.

The prevalence of HIV/AIDS in prisons worldwide varies considerably, as shown in a number of recent studies (see for example, Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, 2006; Lines and Stoever, 2005; Niveau, 2006). According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, the prevalence of HIV in state prisons in the United States is six to ten times higher than in the general community, and it is estimated that one-quarter of the U.S. population infected with HIV spends some time each year in prison. By the end of 2003, 2% of those in state prisons and 1.1% of those in federal prisons were infected with HIV. The geographic distribution of cases of HIV/AIDS is, however, uneven. In areas with low prevalence, such as North Dakota and Montana, just 0.2% of the total prison population is HIV-positive. The highest rates of infection were found in the Northeastern states, with, for example, 7.6% prevalence in the state of New York – which represents more than one-fifth of all HIV-positive prisoners in the United States.

For Africa, there are few prevalence data available. However, given what is known about the high-risk behavior of prisoners before their incarceration, the high-risk profile of the prisoner demographic, and the risk of transmission inside prison, most researchers agree that HIV prevalence in African prisons is twice that of the prevalence among the same age and gender in the general population. For example, the South African Institute for Security Studies has reported that 41% of the South African prisoners are currently living with HIV/AIDS – an increase by 750% since 1995. Zambia, Cote d’Ivoire, and Nigeria have also reported high rates of HIV in their prisons.

In Europe, the prevalence of HIV cases in prison facilities is also an important concern, particularly in Eastern Europe, where there are high rates of HIV infection among people who inject drugs while in prison. Various sources have reported very high rates of HIV among prisoners in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Moldova, and the Russian Federation. From 1996 to 2003, HIV prevalence in Russian prisons increased more than 40-fold from under 1 per 1000 prisoners to 42.1 per 1000 prisoners. In Ukraine, between 15 and 30% of prisoners tested HIV positive in 2005 (Dolan et al., 2004; Roshchupkin, 2003). Other countries, such as England, Belgium, Finland, and Ireland, have successfully targeted injecting drug users with interventions early in the epidemic and have HIV prevalence rates among prisoners of less than 1%.

Hepatitis is another blood-borne viral infection that is predominantly driven by unsafe drug injection practice and can also be sexually transmitted. Rates of hepatitis infection in many prison systems are even higher than are rates of HIV infection, although the three types of hepatitis have different degrees of seriousness. For hepatitis A, the prevalence of the virus in prisoners seems to be the same as that in the general population, and although transmission can occur through close personal contact, only one epidemic has been reported to date in a prison in Australia. Published studies of hepatitis B and C in the prison setting have been summarized by Lines and Stoever (2005) and Niveau (2006) and include those from Australia, Taiwan, India, Ireland, Denmark, Scotland, Greece, Spain, England, Brazil, Ukraine, the United States, and Canada. The vast majority of these studies have reported that between 20 and 40% of prisoners are living with hepatitis. In Ukraine, however, rates of up to 95% were found in early 2005.

Although there are limited international data on the prevalence of tuberculosis infection in prisons, some reports estimate that it is around five to ten times the national average. In some regions of the world, TB is up to 100 times more common in prisons than in the community. People incarcerated are at high risk for tuberculosis, and case rates are among the highest ever recorded in any population. Moreover, some prisons report high levels of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) relative to the general population, which is an issue of great concern. In some countries, the number of tuberculosis cases in prisons constitutes a large proportion of the total number of cases.

The U.S. National Commission on Correctional Healthcare reported that in the United States, released prisoners constituted 33% of all Americans with TB in 1996. A report of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggests that in 2003, although 0.7% of the total U.S. population was confined in prisons and jails, 3.2% of all TB cases nationwide occurred among residents of correctional facilities. For California and New York, CDC reports that TB rates in prisons are 10 to 15 times greater than in the general populations of those states. TB in U.S. prisons is concentrated increasingly among the most disadvantaged populations, particularly detained immigrants, who are arriving largely from countries with a high prevalence of TB, such as Mexico, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

In Europe, the picture is especially bleak for Russia. There, at least 60% of all those infected with MDR TBare in prison (see, for example, Coninx et al., 2000; Lafontaine et al., 2004). It is estimated that there will be about 75 000 new cases annually in the Russian civilian population (for a population of 159 million), whereas in Russian prisons there will be 40 000 new cases, for a population of 900 000. Thus more than half the number of new tuberculosis cases will occur in prison. Tuberculosis epidemics and cases of interprisoner transmission have also been described in the last decade in prisons in France, Italy, Spain, England, and other European countries (Lines and Stoever, 2005).

Although the prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) like chlamydia, gonorrhoea, genital warts, herpes, Trichomonas vaginalis, and syphilis in prisons reflects the spread of these infections in the community, they often remain undiscovered in prisons and can cause serious health problems. As a substantial number of prisoners come from high HIV-prevalence areas, the risk of transmitting these infections is high, especially because in many areas of the world medication and treatments against STIs are not available.

It is important to note the close epidemiological linkages between these diseases, which pose an additional risk for transmission in prison settings. For example, in many prison systems high rates of HIV infection are exacerbated by high rates of hepatitis B and C. The presence of untreated STIs also increases the risk of HIV transmission. What is probably of greatest concern for the transmission of tuberculosis in prisons, however, is the increasing number of people entering prison with HIV. HIV weakens the immune system, leading to reactivation of latent TB infection and the rapid progression to disease in those recently infected with TB. Projections in other countries have shown, that in the presence of a moderate HIV/AIDS epidemic, TB may become uncontrollable, even within the framework of a well-designed TB program. A double infection of HIV and TB in a confined population like a prison is therefore potentially disastrous.

Disease Transmission In Prisons: Risk Factors And Intervention Opportunities

So why does the prison population seem to be so much more vulnerable to infection with serious diseases like HIV/AIDS, TB, and hepatitis than the general population? There are a number of risk factors that are typical for prison settings and that influence the heightened danger of disease transmission in prisons. Some of these health risks are related to the socioeconomic background of the prison population, others to the high-risk behavior patterns of prisoners, and a third category of risks is directly related to the prison environment itself.

Composition Of The Prison Population

The prison population is different from the general population for several complex social reasons. Prisoners are often poor and undereducated and come from marginalized and disadvantaged social groups, such as migrants or ethnic minorities. These groups often did not have access to care in the public health sector before they came to prison and often had never been treated appropriately, even for infectious diseases like HIV, tuberculosis, hepatitis, or STIs. Therefore, many prisoners already had substantial unmet health needs before confinement.

The generally poor health status of prisoners is further exacerbated by the overrepresentation of at-risk populations in prison. In this context the incarceration of drug users is of particular concern. A significant proportion of the prison population is made up of people who have been convicted of offenses directly related to drug use, drug trafficking, or behaviors brought about by drug use. Evidence from the United States indicates that approximately 80% of injecting drug users (IDUs) have a history of imprisonment. In Europe the proportion is at least 50% (Lines and Stoever, 2005). Despite the sustained efforts of prison systems to prevent drug use by prisoners, the reality is that drugs can and do find their way into prisons. No country has to date been able to eliminate drug use in prisons. Even though drug injection is overall less frequent in prison than in the community, each injection presents a higher risk because of the use of contaminated equipment and sharing of syringes.

The treatment of drug addiction during incarceration is increasingly seen as a crucial part of disease prevention in prison because intravenous drug consumption is one of the major factors influencing rapid HIV and hepatitis transmission. The treatment options include the management of withdrawal on admission (drug demand reduction) as a gradual detoxification, proceeding to abstinence-oriented treatment or long-term substitution maintenance.

In addition to in-prison programs, the criminal justice system may refer drug offenders to treatment through a number of alternatives to imprisonment. This approach is consistent with more advanced psychosocial and medical models of addiction. Alternative programs for drug users can include diversion, stipulating treatment as a condition of probation or pretrial release, and commissioning specialized courts that handle cases for nonviolent offences involving drugs. Well-targeted treatment programs, in which public health and criminal justice personnel collaborate on the screening, placement, monitoring, and supervision of the participants, can contribute to a reduction in re-offending.

Behavior Patterns Of Risk Groups

The overrepresentation of high-risk populations in prisons is accompanied by activities and behavior patterns that favor the transmission of infectious diseases or increase the vulnerability of prisoners. This is especially relevant for the transmission of blood-borne diseases, like HIV/AIDS or hepatitis.

Sexual relations between prisoners are a major but poorly documented factor of infectious disease transmission in prisons. Although risk behavior studies within prisons are likely to underrecord the true amount of sexual activities, several studies have provided evidence that significant rates of same-sex activities occur in prisons, despite the fact that sexual activity is illegal in most prison systems. Sexual contact in prisons is often secretive and disorganized and is likely to take place without any protection. It includes also various kinds of nonconsensual sexual activity, for example, submission based on intimidation or in return for protection or other favors.

Intravenous drug consumption as described previously, in which injecting equipment is shared, is a very efficient route of transmission for HIV and hepatitis B/C, much more so than sexual contact. It is also the main factor determining levels of infection among prisoners. Often it is more difficult to smuggle syringes than drugs into penal institutions, making access to sterile syringes very limited.

Tattooing, scarification procedures, and body piercing are part of prison culture and prevalent in many countries. Carried out in unhygienic conditions and with shared equipment, tattooing poses a high risk of hepatitis C and, to a lesser extent, HIV transmission. Although conclusive clinical evidence of disease transmission via tattooing is not available, several studies link tattooing and transmission of blood-borne diseases in prisons.

To lessen the harmful consequences of individual risk behavior, preventive medicine uses so-called harm-reduction measures to respond to the risks of unprotected sex and sharing of infected needles or tattooing equipment. The concept of harm reduction also includes drug-substitution treatment, which has been mentioned in the previous section. Harm reduction measures have rapidly expanded as part of community health programs in many Western countries in recent years, and there is now scientifically sound evidence showing that they can be important preventive health measures.

The introduction of harm-reduction measures in a prison setting, especially needle exchange programs, is frequently opposed on the grounds that these measures may be perceived as supporting illegal activities that have contributed to many prisoners being incarcerated in the first place. There is also the fear that they may encourage nonusers to experiment with injecting drug use or use needles as weapons, thereby undermining the prison security system. Given the high risk of disease transmission by sexual activity and drug use in prison, however, harm-reduction measures are increasingly applied in prison systems.

Condom use is internationally accepted as the most effective method for reducing the risk of HIV transmission, and prison authorities in many countries have made condoms available to prisoners in recent years. No prison system that has adopted a policy of making condoms available has subsequently reversed the policy, and the number of systems in which condoms are being made available has continued to grow.

However, despite the availability of condoms, barriers to their use exist in many prisons. Homosexual activity is likely to be highly stigmatized or even illegal in prisons, which can result in prisoners being reluctant to use safer sex measures for fear of identifying themselves. Furthermore, condoms, dental dams, and lubricants often are not available easily or discretely or are not available on a 24-hour basis.

Needle and syringe exchange/distribution programs have proved to be an effective HIV prevention measure, ensuring that individuals do not have to share their equipment and so reducing the risk of HIV and hepatitis transmission among people who inject drugs and their sexual partners (see, for example, Dolan, 2004; Kerr and Ju¨ rgens, 2004). As a result, many countries have implemented these programs within community settings to enable people to minimize easily and discretely their risk of contracting or transmitting blood-borne infections. Despite the success of these programs in the community, only a small number of countries have extended syringe exchange programs into prisons. At present, there are syringe exchange programs in prisons operating in six countries – Switzerland, Germany, Spain, Moldova, Kyrgyzstan, and Belarus. The evidence from these countries demonstrates that such programs do not endanger staff or prisoner safety, do not increase drug consumption or injecting, reduce risk behavior and disease transmission, and can reduce the number of overdoses.

Bleach programs for prisoners who inject drugs, as a means of disinfecting injecting equipment before reusing it, have been adopted by some prison systems, particularly where access to sterile syringes is not available. Disinfection can, however, only be seen as a secondary strategy to syringe exchange programs, and their effectiveness is largely dependent on the method used. WHO reported in 2005 that concerns that bleach might be used as a weapon proved unfounded, and there have been no such instances in any prison where bleach distribution has been tried.

Prison Conditions

In the vast majority of prison systems, health care is provided by the ministry or government department responsible for prison administration, not by the ministry responsible for health care in the community. Against the background of underfunded prison systems, this means that the health needs of the prison population are often given a low political priority, conflicting with security, judicial, or legal requirements. Although conditions of prison health care and detention vary greatly from country to country and facility to facility, standards in most countries are shockingly low. Two factors especially influence the health status of prisoners: the living conditions themselves, with the overcrowding of facilities being of special concern, and the access to health care, treatment, and prevention measures in prison.

Prison Overcrowding

Factors that increase the possibility of air-borne diseases like tuberculosis in the prison setting include the practice of housing prisoners in unhygienic conditions and in spaces that do not meet the international minimum standards for size, lighting, and ventilation; providing a poor diet; and limiting their access to the open air. One of the key factors contributing to and aggravating the effects of these poor conditions is prison overcrowding. The larger the number of people in a confined space and the poorer the conditions, the easier the diffusion of diseases transmitted by physical contact and air. Overcrowding can also trigger subsequent stressors like prison violence, fighting, bullying, sexual coercion, and rape, thereby aggravating the transmission of blood-borne infections.

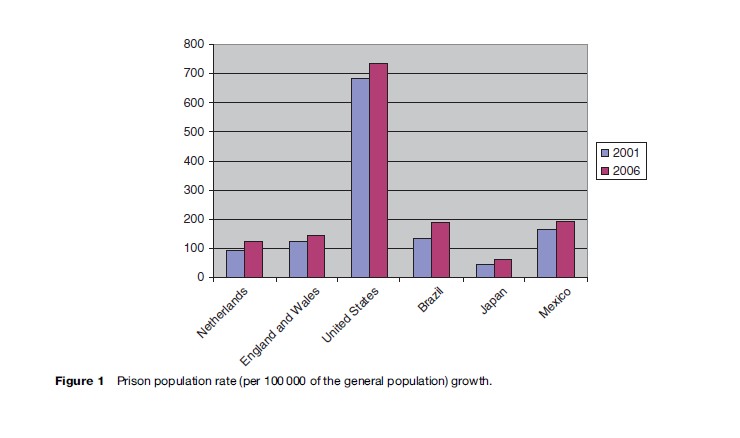

Overcrowding exists in most prison systems throughout the world due to a worldwide increase in the prison population over the last 10 years (see Figure 1; for information on prison population rates and growth, see Walmsley, 2004; World Prison Population List, 2005). The prison population in the United States alone has risen from 1.86 million to more than 2 million since 1999, making it pro rata, and also in actual numbers, by far the biggest user of prisons in the world. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reported in 2005 an annual growth of the prison population in the federal system of 7.4% per year since 1995. At the end of 2004 the federal prison system was operating at 40% over capacity.

Throughout Europe in the 1990s, the prison population grew by more than 20% in almost all countries and by at least 40% in one-half of the countries. In mid-2006, with a prison population rate of 145 per 100 000, England and Wales had more prisoners per head of the population than any other European country, apart from Luxembourg. This rate represented a 15% increase since 1999. The largest rise in the prison population in Europe in recent years has been in the Netherlands, which increased 42%, from 14 000 to 20 000 between 2000 and 2005.

Prison populations are also growing in many other parts of the world. Notable increases over the same period include Brazil (70%), Japan (40%), and Mexico (37%). Prison populations have also risen 64% in countries in Africa, 79% in the Americas, 88% in Asia, and 69% in Oceania. Only in a few countries in the world, most notably Japan and Finland, have incarceration rates remained broadly stable or even declined in recent decades.

Many Western countries have decided to respond to the growing numbers of prisoners and the harmful effects of prison overcrowding by building new prisons. Practice has shown, however, that this is not a sustainable solution. Several European states decided to start extensive programs of prison building only to find their prison populations rising in parallel with the increased capacity. More effective in the medium and long term can be a shift in sentencing policy, including the wider use of alternatives to prison, such as mediation, community work, and administrative and monetary sanctions, especially for young or nonviolent offenders.

Prison Health Management

Health services in prison are often underfunded, leading to restricted access to health care for prisoners. Insufficient equipment, infrastructure, staffing, and expertise can affect the full circle of care, including screening and testing, treatment, transmission control and disease surveillance, as well as prevention measures. Administrative problems often compound these limitations and include delays in reporting laboratory results and diagnosis, lengthy administrative procedures to arrange transfer and admission to a place of treatment, and poor communication and record-keeping procedures. Case finding may be managed independently of treatment, and different authorities may use differing procedures. Lack of standardization may result in interruptions in treatment or in over or undertreatment of patients. This is especially relevant in the case of tuberculosis, where erratic treatment can provoke drug resistance in patients, leading to increased mortality.

If diagnosis and treatment for infectious diseases are not available or inadequate, prisoners may seek their own solutions. In some countries, access to health care, transfer to an area with better living conditions, or contact with visitors can be bought, using a variety of ‘currencies’ – money, cigarettes, alcohol, drugs, or sex. Prisoners may also purchase samples, such as sputum, known to give positive or negative test results from other prisoners, to enable them to join a special treatment program or to leave one. The presence of unofficial payment systems is especially common in situations where prison staff are not paid regularly or receive very low salaries.

Where prisons are unable to provide prisoners with access to adequate health services, there is reason to argue that the prisoners should have access to parallel provision in the general community, thereby avoiding duplication of resources and achieving standardized procedures. After their release, infection control is easier to maintain when the treatment procedures are not interrupted and the responsibilities for the treatment of released prisoners are clear. From a public health point of view, the time spent in prison provides an exceptional opportunity to come into contact with a population that is generally marginalized and hard to reach, especially with regard to preventive measures.

In some European countries political pressure from public health professionals has led to a closer relationship between the prison and public health services. Some countries have considered the collaboration of civilian hospital wards and laboratory services to save costs, streamline treatment procedures, and strengthen disease surveillance and reporting systems. In other cases, the services have been completely integrated, as for example in Norway (where prison health has been under the auspices of the Ministry of Health since 1988), France (since 1994), and Italy (since 2000). Evidence from these countries indicates that treatment and prevention outcomes in prisons improve considerably when health ministries take an active role and work in close collaboration with penitentiary systems (International Centre for Prison Studies, 2004; Nicholson-Crotty, 2004).

Public Health And Human Rights: A Double Rationale For Intervention

As the previous section has shown, special approaches to prison health care are required. However, this does not mean that the final outcome of treatment and prevention efforts should be different from that in the community. Governments have the duty and should have the interest to protect prisoners from health risks according to a double rationale: human rights and public health. This section describes how these two lines of argument are set out, what instruments they employ, and what opportunities they may provide.

Imprisonment And Human Rights

Throughout the second half of the 20th century an interest in prisoners’ rights has developed, and the traditional concept of a prisoner as a ‘slave of the state’ with no right but that of life has been increasingly condemned. In 1948 the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provided that no person should be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. Today international human rights standards require that prisoners retain all civil and human rights, except those they are deprived of as a result of their incarceration. These include the right to the ‘highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’ (International Covenant on Economic, Social & Cultural Rights, Art. 12).

Several international standards address explicitly and in detail conditions of imprisonment or the rights of prisoners. The most prominent international prison standards are the following:

- Standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners (UN, 1957), later extended to persons detained without charge, such as in places other than prisons (UN, 1977)

- Principles of Medical Ethics relevant to the Role of Health Personnel, particularly Physicians, in the Protection of Prisoners and Detainees against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UN, 1982)

- Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (‘The Beijing Rules,’ UN, 1985)

- Body of principles for the protection of all persons under any form of detention or imprisonment (UN, 1988)

- Basic principles for the treatment of prisoners (UN, 1990)

- Standard Minimum Rules for Non-custodial Measures (‘The Tokyo Rules’, UN, 1990)

- European Prison Rules (Council of Europe, 2006).

Many of these rules and regulations are relatively specific, governing not only the imposition of prison sentences and the release of prisoners but also the actual regimes to be followed, including health care and disease prevention measures. The international standards go far beyond a broad and general recognition of prisoners’ rights, as outlined in international human rights law. Comprehensive comments on the standards, as well as guidelines for their implementation in prison management practice, have been provided by Penal Reform International (2001) and Coyle (2002).

Imprisonment And Public Health

Another important consideration supports the implementation of humane prison conditions and international human rights standards in prison: the concern for public health.

Prisons have always been potential reservoirs of infectious diseases, and the risk of spread of tuberculosis from prison to the community by released prisoners has been established for a very long time. However, due to the closed nature of prisons, the health of prisoners did not come to the attention of the public at large. It was only in the context of the international mobilization created around the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the early 1990s that the issue of prisoners’ rights to health was given new visibility. The need to implement effective preventive measures to stop transmission of epidemics to the community made prisons a fundamental issue of public health concern.

In 1993, the WHO issued technical recommendations for the management and prevention of HIV infection in prisons to meet these concerns. These recommendations were the first, and remain the most prominent to date, international standards focusing specifically on prison health issues, especially HIV/AIDS, drug use, and tuberculosis. These guidelines complement and fine-tune the international prison standards in many ways, bringing the issue of health in prison to a new level of regulation.

The most important international prison health standards are as follows:

- WHO guidelines on HIV infection and AIDS in prison (1993)

- Joint UN Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Statement on HIV/AIDS in Prisons (1996)

- International guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights (OHCHR/UNAIDS, 1998)

- Recommendation No R(98)7 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States concerning the Ethical and Organizational Aspects of Health Care in Prison (Council of Europe, 1998)

- WHO/ICRC Guidelines for Tuberculosis Control in Prisons (WHO/ICRC, 1998)

- WHO/Council of Europe: Prison, Drugs and Society – A Consensus Statement on Principles, Policies and Practices (2002)

- WHO: The Moscow Declaration: Prison Health as part of Public Health (2003).

These guidelines do not stand alone but have been supported and promoted by numerous reports, legal scholars, and medical experts through a number of international networks. In 1995, the WHO Regional Office for Europe established the Health in Prisons Project to create a forum for countries to share experiences in dealing with the major challenges of prison health and to disseminate best practices. Other initiatives with an active role in prison health promotion are the Pompidou Group of the Council of Europe, the International Centre for Prison Studies, the European Network on HIV/AIDS Prevention in Prisons, and the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network.

Outlook

The common ground for both the human rights and public health arguments for better prison health is the principle of equity, whereby access to care and prevention measures in prison should be equal to that in the community. Equity in health means that people’s needs, rather than their social privileges, guide the distribution of opportunities for well-being in order to eliminate disparities in health and in health’s major determinants, which are systematically associated with membership in less privileged or especially vulnerable social groups. Within the human rights discourse, equity is increasingly serving as an important nonlegal policy term aimed at ensuring fairness. Its importance is reinforced further by the focused attention on vulnerable and disadvantaged groups in international human rights instruments. Within the public health discourse, the principle of equity is used as a basic supposition for the treatment and care of vulnerable groups to the ‘highest attainable standard of health,’ which manifests itself in targeted health programs and open access to health services.

Problems at the level of prison health care are often aggravated or even created by societal determinants of health. To achieve equity in prison health, scholars and practitioners acknowledge that the focus of health-care provisions needs to broaden. A purely medical approach might not be sufficient to tackle the specific health problems of prisoners. Even more, the concentration of prison health as a stand-alone concept risks isolating and thereby marginalizing the problems of the prison population.

In this context, this research paper has discussed three key prison and penal policy measures that can improve prison health care:

- The introduction of alternatives to imprisonment, especially for drug addicts and nonviolent crimes, to reduce prison overcrowding and improve conditions

- The full introduction of harm-reduction measures in prisons, including substitution therapy and needle exchange, as supported by the World Health Organization

- The strengthening of links between public and prison health services to improve prison health management and disease control.

Acknowledgment of the contribution of prison health to health inequalities and an increased attention to wider health and criminal justice policies influencing these inequalities will not only effectively tackle both the problems of prisoners as a group especially vulnerable to health problems but will also benefit the health of the public.

Bibliography:

- Canadian, HIV/AIDS Legal, Network (2006) HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C in Prisons. Available at: http://www.hivlegalnetwork.ca/site/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/HIV-hepC_Prisons-ENG.pdf

- Coninx R, Maher D, Reyes H, and Grzemska M (2000) Tuberculosis in prisons in countries with high prevalence. British Medical Journal 320: 440–442.

- Coyle A (2002) A Human Rights Approach to Prison Management. Handbook for Prison Staff. London: International Centre for Prison Studies.

- Dolan K, Kite B, Black E, et al. (2004) Review of Injection Drug Users and HIV Infection in Prisons in Developing and Transitional Countries. London, England: Centre for Research on Drugs and Health Behavior.

- International Centre for Prison Studies (2004) Prison health and public health: The integration of prison health services. Conference Report. London: International Centre for Prison Studies.

- Kerr T and Ju¨ rgens R (2004) Syringe Exchange Programs in Prisons: Reviewing the Evidence. Montreal, Canada: Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network.

- Lafontaine D, Slavuski A, Vezhnina N, and Sheyanenko O (2004) Treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Russian prisons. Lancet 363: 246–247.

- Lines R and Stoever H (2005) HIV/AIDS prevention, care, treatment, and support in prison settings. Background Notes for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Draft Paper. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- Nicholson-Crotty J (2004) Social construction and policy implementation: Inmate health as a public health issue. Social Science Quarterly 85(2): 240–256.

- Niveau G (2006) Prevention of infectious disease transmission in correctional settings: A review. Public Health 120(1): 33–41.

- Penal Reform International (2001) Making Standards Work: An International Handbook on Good Prison Practice, 2nd edn. London: Penal Reform International.

- Roshchupkin G (2003) HIV/AIDS prevention in prisons in Russia. In: Lokshina T (ed.) Situation of Prisoners in Contemporary Russia, pp. 203–213. Moscow, Russia: Moscow Helsinki Group.

- Walmsley R (2004) Global Incarceration and Prison Trends. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

- World Health Organization (2005) Status paper on prisons, drugs and harm reduction. Report of the WHO. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization.

- World Prison Population List (2005) Report of the ICPS. London: International Centre for Prison Studies.

- Bollini P (ed.) (2001) HIV in Prisons. A Reader with Particular Relevance to the Newly Independent States. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization.

- Bone A, Aerts A, Grzemska M, et al. (2004) Tuberculosis control in prisons: A manual for programme managers. Report of the World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO/ICRC.

- Coyle A and Stern V (2004) Captive populations: Prison health care. In: Healy J and McKee M (eds.) Accessing Healthcare: Responding to Diversity. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Delgado M and Humm-Delgado D (2006) Health and Healthcare in Prisons. Issues, Challenges, and Policies. New York: Praeger.

- European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (2002/2004) The CPT standards. Report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

- Farmer P (2003) Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Gatherer A, Moller L, and Hayton P (2005) The World Health Organization European Health in Prisons Project after 10 years: Persistent barriers and achievements. American Journal of Public Health 95: 1696–1700.

- Human Rights Watch (2003) Ill-Equipped: US Prisons and Offenders with Mental Illness. Washington, DC: Human Rights Watch.

- Kerr T, Wood E, Betteridge G, Lines R, and Ju¨ rgens R (2004) Harm reduction in prisons: A ‘‘rights based analysis.’’ Critical Public Health 14(4): 345–360.

- MacDonald M (2005) A study of health care provision, existing drug services and strategies operating in prisons in ten countries from Central and Eastern Europe. Report of HEUNI. Helsinki, Finland: HEUNI.

- Macneil JR, McRill C, and Steinhauser G (2005) Jails, a neglected opportunity for tuberculosis prevention. American Journal for Preventive Medicine 28(2): 225–228.

- Schalkwyk A (2005) Killer corrections: AIDS in South African Prisons. Harvard International Review 27(1): 6–10.

- Stern V (ed.) (1999) Sentenced to Die? The Problem of TB in Prisons in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. London: International Centre for Prison Studies.

- Sto¨ ver H, Hennebel LC, and Casselmann J (2004) Substitution treatment in European prisons. A study of policies and practices of substitution in prisons in 18 European countries. Report of the European Network of Drug Services in Prison. London: ENDSP.

- World Health Organization (2000) Preventing suicide: A resource for prison officers. Report of the World Health Organization. WHO: Geneva, Switzerland.