Sample Health Surveys Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Information collected by health surveys is used by public health officials to plan, conduct, and evaluate programs; by elected officials to inform policies and legislation; and by researchers to understand the health status of the population, the determinants of health, and the health care system. While such surveys are sponsored and carried out by many private entities, core information is generally obtained through relatively large, multipurpose, government-sponsored data collection systems; these will be the focus here, although most of the issues discussed pertain to all health surveys.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The World Health Organization definition of health as a state of physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity provides the starting point for health surveys. The multidimensionality of this definition requires different survey methodologies. Since health is both a biologic and a social construct, health surveys must reflect this duality. Major topics to be covered include aspects of survey design, conceptualization and measurement of health status, determinants of health, summary measures of health, health care utilization and health behaviors. The effect of recent technological advances on data collection methods are discussed as are the growing opportunities for data linkage and the future challenges of providing access to data while protecting confidentiality and privacy.

In the late 1990s, 9.2 percent of the United States population reported they were in fair or poor health; 14 percent of children under 18 years of age had no health insurance coverage; 79 percent of children 19–35 months old were up to date on immunizations; 25 percent of adults were smoking cigarettes; and 24 percent were hypertensive (National Center for Health Statistics, NCHS 1999). Such information is used by public health officials to plan, conduct and evaluate programs; by elected officials to inform policies and legislation; and by researchers to understand the health status of the population, the determinants of health and the health care system. Information on the health of a population can be obtained through a variety of data collection approaches; health surveys represent one mechanism.

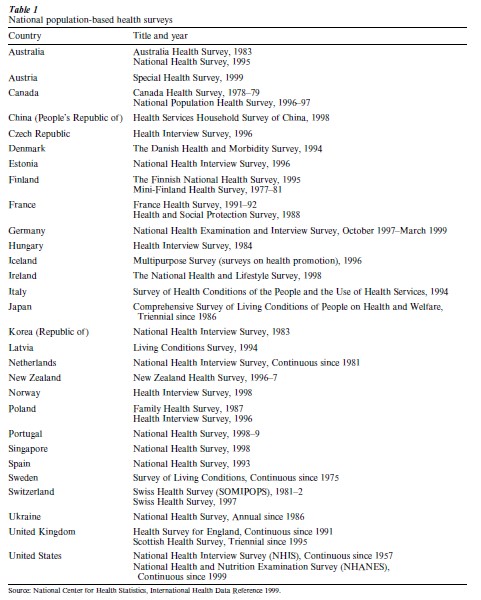

While such surveys are sponsored and carried out by many private entities, core information is generally obtained through relatively large, multipurpose, government-sponsored data collection systems; these will be the focus here, although most of the issues discussed pertain to all health surveys. These surveys are used to profile the health of the population, to track demographic shifts and trends, and to monitor change in health and health care. In addition, the data are also used to investigate epidemiologic relationships between risk factors and health outcomes and to provide information for prevention, evaluation, research, planning, and policy. Many nations include the conduct of general purpose health surveys in their statistical systems. Table 1 provides a list of countries and the title and year of their most recent general health survey (CDC, NCHS 1999). It is tempting to directly compare the results of these surveys, but cross-national cultural differences and variation in the nature of health care systems as well as in survey designs must be taken into account when making international comparisons.

1. Definition And Operationalization Of Health

The World Health Organization definition of health as a state of physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity provides the starting point for health surveys (WHO 1948). However, because this definition is broad, complex, and multidimensional, it is difficult for any single survey to collect all the needed information. Depending on the specific objectives of a particular survey, there will be variation in the universes from which the samples are drawn and in the health and health-related information obtained. Since health is both a biologic and a social construct, health surveys must reflect this duality. In fact, these inter-relationships between the biological and social aspects of health are often best approached through health surveys, and advances in technology have made it increasingly possible to incorporate direct measures of biologic aspects of health into more traditional surveys.

2. General Design Issues

Health surveys can either obtain information directly from individuals (the subject or an informant) or can rely on administrative records. A wide range of sampling methodologies, sampling frames, and data collection strategies are used depending on survey objectives and the characteristics of the area in which the survey is done. Countries that have universal health care with centralized administrative systems can utilize designs that would be inappropriate in countries with less well-developed or decentralized health care systems. The simplest sampling scheme is a simple random sample of a population obtained from a complete and up-to-date list such as from a census of the population or a centralized health care system. In the case of surveys of persons, if such lists do not exist, area sampling can be used with clustering to reduce costs. In order to be able to report information on subpopulations of interest as defined by geography and/or demographic, socioeconomic or health characteristics, designs often include oversampling of these groups. It is often necessary to incorporate screening into designs to achieve this objective. Information can be obtained either by mail, by phone, by in-person interview, or by some combination of modes depending on the ability of the researchers to contact the population using these means. The latter two modes can also incorporate computer-assisted technologies, and the use of the Internet for the administration of health surveys is being investigated.

In general, obtaining information directly from the survey subject provides more reliable and valid health data. However, this is not universally true and depends on the nature of the information sought and the characteristics of the subject (Moore 1988). For example, while accurate information on risk behaviors among adolescents can probably only be obtained from the adolescent in a private environment, adolescents are not good reporters of health care utilization or household income. Even more problematic is the situation where a health condition does not permit a subject to respond for himor herself. Since eliminating the subject from the survey would seriously bias the results, a proxy respondent is often used.

While necessary, the use of proxy respondents does introduce a source of error into health surveys, particularly longitudinal surveys. Obtaining information on the relationship of the proxy to the subject as well as the conditions leading to the use of a proxy can reduce this error. In other cases, subject reporting is fraught with a great deal of measurement error. For example, information on the characteristics of an insurance plan is usually better obtained from the insurer rather than the person holding the insurance. Finally, reliable assessment of specific types of morbidity, risk factors, and mortality requires direct measurement through physical examination or access to administrative records from health care providers.

Many health surveys limit their population of interest. For example, it is common for health surveys to only include the noninstitutionalized population. The dramatic differences in the living conditions of the institutionalized and noninstitutionalized populations make it difficult to design survey methodologies that would apply in all situations. The military population is also often excluded from general health surveys. The scope of the universe needs to be clearly defined, especially if populations that differ in their health status are omitted—such as persons residing in nursing homes.

When obtaining information directly from the population is inefficient or would result in either poor data quality or high costs or both, an alternative is to sample from existing records that were created for other purposes. Information on health care utilization for specific conditions is more easily obtained from hospital or provider records than from a population sample given the relative rarity of the phenomena of interest. The vital statistics system can also be considered a survey of administrative legal records for the purpose of describing the health of the population. Administrative systems, in addition to providing basic health information, are often used as sampling frames for population based surveys. They are very attractive for this purpose as they eliminate the need to identify members of the population who have the characteristics of interest.

3. Content

Information collected on health surveys can be divided into three general types: (a) health status; (b) determinants or correlates of health including health behaviors; and (c) health care utilization. In addition, information is also collected on demographic and socioeconomic factors that affect health. For illustrative purposes, examples will be provided from two major health surveys conducted in the United States by the National Center for Health Statistics, CDC: The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis), and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (http://www.cdc.gov/nhanes). Many statistical agencies work closely with counterparts in other nations in the design of their health surveys, thus, many observations regarding the NHIS and NHANES apply to similar surveys in other countries. Attempts to standardize various parts of health surveys have increased in recent years.

The NHIS is a principal source of information of the health of the civilian noninstitutionalized US population. Conducted annually since 1957, the NHIS currently collects information through computer assisted in-person interviews from approximately 40,000 households covering 100,000 people. Conducted about once a decade, NHANES is based on detailed physical examinations in addition to in-depth interviews. A nationally representative probability sample of the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population is interviewed at home and then invited to visit a Mobile Examination Center (MEC) for a standardized physical examination of about four hours, including a physician’s exam, physical measurements, blood and urine tests, and nutritional assessments.

4. Overall Health Status

As noted above, health status is a multidimensional concept, requiring multiple indicators and multiple methodologies for adequate measurement. Several different indicators of health status are usually included in health surveys, including single summarizing measures; questions relating to disease incidence and prevalence; and questions relating to functioning (physical, cognitive, emotional, and social). Health status measures also vary by whether they are based on objective information obtained from standardized examinations or medical records or from information obtained from the individual or a proxy. To be most effective, individual health surveys should capture a variety of aspects of health status so as to provide a more comprehensive and complete assessment of health status than would be possible from any single strategy. Measures of health status should also be constructed to be useful in epidemiologic analyses of risk factors as well as for monitoring trends.

The subject’s self-assessment of his her health status as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor is a popular summary indicator of health status. This measure has been shown to be highly correlated with other measures of health status and is predictive of mortality and admission to long-term care facilities (Idler and Angel 1990). However, this measure can be problematic when used to monitor change over time. The means by which individuals evaluate various aspects of health have been shown to be affected by contextual parameters. Implicit in self-perceived health status is the individual’s evaluation of his her health status against some unstated standard. Societal norms act to define the standard, but the norms and the standards change in response to a variety of conditions. The reporting of general limitation of activity has also been shown to be affected by changes in such things as the criteria used by government agencies in determining eligibility for disability benefits (Wilson and Druny 1984). Thus, observed changes in the indicator may not reflect changes in underlying health status.

5. Medical Conditions

A variety of approaches can be used to measure disease incidence and prevalence including: diagnosis by a health care provider; symptomatology (if an appropriate symptom battery exits); or medication use. Additional information of interest related to conditions includes date of onset, the use of health care services, and the impact of the condition on the individual’s ability to function. Severity of condition is often inferred from the type of medications or health care services used or the nature of the impact of the condition. In examination surveys, diagnostic testing adds to the information available on the prevalence of conditions. Most important, direct physical exams allow for the measurement of previously undiagnosed conditions.

A major issue in the collection of condition data is the number of conditions to be considered. Condition checklists can be used to obtain information on a great number of conditions, but in most cases, only a minimal amount of information on any given condition is collected. In addition, long checklists are difficult to administer and result in reporting errors. However, the use of comprehensive lists does allow for the ascertainment of co-morbidities. An alternative is to obtain more detailed information on a select group of conditions. Criteria such as the prevalence of the condition or the potential impact for the individual and the health care system are used to select the target condition. In the NHIS, for example, information is obtained for adults on heart disease, diabetes, cancer, pulmonary diseases, depression, and arthritis.

Some surveys, such as the NHIS (until 1997 when a major questionnaire redesign was fielded), limit their focus to conditions that result in the receipt of medical care or in activity restriction, thus placing more emphasis on the impact of the condition than on the fact that a diagnosis had been made or symptoms reported. This provides a somewhat more concrete referent for the questions being asked which should result in improved data validity and reliability. However, limiting the definition of health problems to those that result in behavior such as seeking care or restricting activity is more appropriate when ill health is primarily the result of acute conditions where onset is clear and there is a closer association between the condition and the behavior. As a result of the ‘epidemiologic transition,’ acute conditions have given way to chronic conditions as the major sources of morbidity. Chronic conditions are more difficult to diagnose, and longer periods are spent in the disease state both prior to and after diagnosis. As a result, the collection of information on symptoms takes on greater importance when investigating chronic conditions that may or may not have been diagnosed. Diagnostic examination or testing is necessary for some important conditions (e.g., hypertension, cancer) which may be asymptomatic in their early or less severe stages.

Requiring that health care use or activity limitation be present in identifying conditions also makes it difficult to investigate social correlates of health status since the definition incorporates a social dimension. Access to sick leave or affordable medical care may be limited by social or economic factors. Persons who do not demonstrate the required behaviors because of these social factors will not be considered as having a health condition.

Examination surveys like the NHANES provide a complementary mechanism for obtaining information on conditions. Self-reported information, similar to that collected on the NHIS on self-perceived health status, disease symptomatology, physician diagnosis, and level of functioning, is obtained from in-home or MEC interviews. In addition, the results of the physical exam, and of the blood and other tests, can be used to objectively measure health status. For example, information on diagnosed diabetes is obtained from the interview, and information on undiagnosed diabetes is obtained from blood tests. Information on functional limitations related to diabetes (e.g., vision and mobility problems) coupled with similar information available from the other components of the NHANES allows for a detailed characterization of an individual’s health status. The information is also used for the investigation of risk factors for disease and for monitoring of functional outcomes.

Information on conditions can also be obtained from surveys of health care providers (hospitals, private physicians, hospital outpatient departments, emergency departments, ambulatory surgery centers, and long-term care). Sampling frames of providers must first be developed. Random samples of discharges, stays, or visits are then selected from the records of a random sample of providers. Information on conditions is routinely found on the medical records in addition to other descriptive information concerning the patient and the encounter. Such survey designs are generally used to obtain information on health care utilization and the health care system, but the information available can be used to study conditions that are associated with medical care.

Health care or provider surveys offer an independent assessment of disease prevalence by approaching the problem from the provider side rather than the patient side. Health care surveys are particularly important since they obtain information on rare conditions that would not be picked up in population based surveys. They also provide larger sample sizes than would be obtained in surveys such as the NHIS and the NHANES. While information is collected on all conditions for which health care is obtained, the nature of the information available is limited to that which would routinely be obtained from records. In addition, the event (e.g., the discharge), rather than the person, is the unit of analysis. For example, while it is possible to estimate the number of hospital stays associated with hip fracture, it is not possible to estimate the number of persons with hip fracture even if one could assume that all hip fractures were admitted to the hospital. An enhancement to health care surveys would be to follow patients after the health care encounter.

Cause of death statistics obtained from a vital statistics system also provide essential information on medical conditions. While not error free, a great deal of effort is put forth to standardize the collection and coding of cause of death (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd9).

6. Functioning

An important component of health status concerns functioning—physical, cognitive, emotional, and social. While conditions relate more to the biologic aspects of health, functioning moves more into the social realm. Information on functional status can be ascertained through objective tests but is most often obtained through direct reporting by the individual or a proxy. Information on functional status encompasses a wide range of activities from the very basic such as raising an arm to the more complex such as working and going to school. Obtaining information on functioning is complicated by the fact that performance is affected not only by physiologic abilities but by the environment as well. A person’s ability to walk may be impaired by a condition that leads to weakened muscles, but with the use of braces or a wheel chair along with appropriate accommodations in the physical environment (e.g., ramps), that individual is mobile and able to carry out appropriate social roles. For some purposes, information is needed on functional ability without the use of assistance of any type. In other cases, functioning ability as measured by usual performance is important. In any case, questions must be specific concerning how performance should be measured. A large number of question batteries have been developed to measure function (McDowell and Newell 1996). Some use only a few questions, focus on the more complex social roles, and do not differentiate between different aspects of functioning (physical, cognitive, emotional, or behavioral). Others are quite lengthy and obtain detailed information on a wide range of activities both with and without assistance.

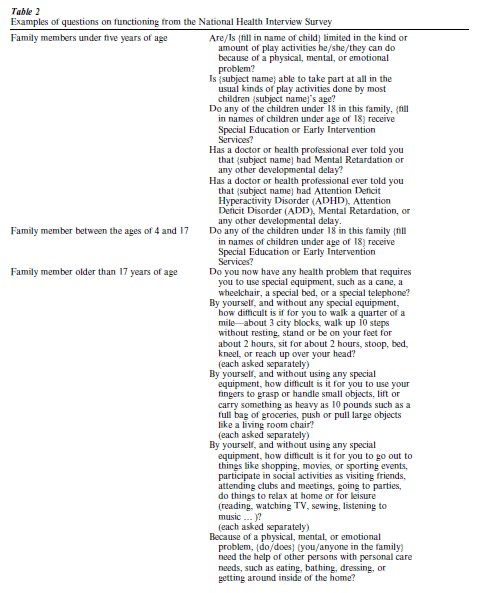

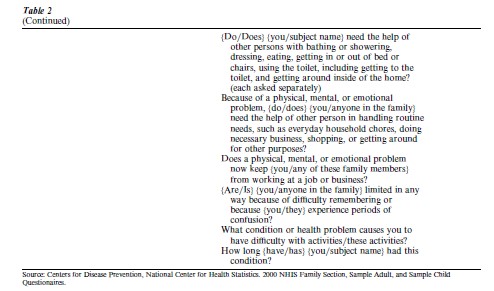

In the NHIS, information is obtained on limitation of activity (i.e., the subject’s ability to perform age-/sex-appropriate roles such as working, going to school, keeping house), activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, dressing, toileting, eating, and transferring), and physical functioning (e.g., walking, bending, and standing). Information is also obtained on the conditions causing the limitation. A subset of the NHIS functioning questions is provided in Table 2.

As for self-perceived health status, measures of functioning are affected by contextual parameters as well as unstated standards against which respondents compare their own functioning. The less explicit the referent standard, the more likely that the response will be affected by external factors. For example, no explicit standard is provided when asking subjects if they are limited in the kind or amount of work they can do. Responses to this question will be affected by the kind of work that the individual thinks he or she should be doing as defined by their own expectations and by the requirements set by government agencies such as disability programs as well as by more objective states of health. This is less of a problem if one is interested in monitoring the impact of health on work. However, it is much more of a problem if the aim is to understand and monitor a more objective measure of health.

Many health surveys are limited to the noninstitutionalized population and therefore do not include those segments of the population in poorest health or with the highest level of functional limitations, such as those in long-term care settings. Special studies of these populations can be carried out and there should be some attempt to combine results from the noninstitutionalized and long-term care populations (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nnhsd/nnhsd.htm, http://www.cds.duke.edu/text/nltcs./html). Changes in the delivery of long-term care with the expansion of transitional establishments have made this an even more important issue for survey designers.

7. Determinants Of Health

Health surveys generally include measures of risk factors, health behaviors, and nonhealth determinants or correlates of health such as socioeconomic status. The range of measures that can be included is wide and varies by survey. Basic demographic and socioeconomic variables are usually included (i.e., age, race ethnicity, education, income, urbanicity, region). Tobacco use, alcohol use, diet, and physical exercise are common health behaviors. In order to identify causal relationships between determinants and outcomes, longitudinal designs are needed. The value of health surveys would be increased by the inclusion of a broader array of potential determinants of health (biologic, psychological, and social).

8. Summary Measures Of Health

There has been considerable interest in the development of summary measures of health in order to more easily characterize and monitor the health status of a population and for use in cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses. There is also increasing interest in developing basic health status indicators comparable to the economic indicators currently in use. These indicators would be used to monitor the effects of public policy and to identify areas where interventions are needed. An overall health measure is very appealing in this context. Many health surveys include the information necessary to calculate the summary measures that have been developed. One such approach is to use a measure of morbidity or health status to transform life expectancy into healthy life expectancy. Examples include Disability Free Life Years, Healthy Life Expectancy, and Years of Healthy Life. Constructs such as these combine measures of the different aspects of health into a single number using a conceptual model that views health as a continuum. The health states along the continuum are assigned numbers that represent the values that either society as a whole or individuals place on that health status. Various methods have been used to determine the values of the different health states. These measures are used to modify duration of life (Erickson et al. 1989).

9. Health Care Utilization

The use of the health care system is a major dimension of health. Information on utilization and related characteristics such as health insurance are collected from person-based surveys and through surveys of administrative records. In person-based surveys, respondents are asked to recall the number of contacts they have had with various health care providers and the nature of the provider and the contact. Information on the receipt of particular services, such as immunizations or mammography, is also obtained. This is often difficult for respondents. Research has shown that reporting of doctor visits drops off considerably when the recall period extends beyond two weeks (Edwards et al. 1996). To address this recall problem, some surveys such as the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) ask respondents to keep detailed diaries of their medical care contacts, obtain the name of the provider, and then contact the providers (with the subject’s permission) to verify the self-reported information (Monheit et al. 1999). Information on utilization can also be obtained from surveys of providers, usually providing more accurate information on the nature of the contact, including the reason for the contact and the services provided. Surveys of providers can also yield valuable information on the structure of the health care system itself and how the characteristics of the system affect access to care and the cost of care.

10. Longitudinal Designs

Most health surveys use a cross-sectional design which provides data for the calculation of population averages and is most appropriate for monitoring changes in health over time. A cross-sectional design is not appropriate for investigating causal patterns or for documenting transition probabilities from one health state to another where change at the individual level needs to be measured. A solution would be longitudinal studies which are expensive and more complicated to field. One alternative is to transform cross-sectional studies into longitudinal studies by linking information from mortality records to the survey data. The United States has developed a National Death Index which allows investigators to track the vital status of their study cohorts by matching identifiers to a complete listing of death certificates. Using a probabilistic matching algorithm, information is provided on the fact, date, and cause of death ((http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/r&d/ ndi). Cross-sectional surveys also can form the baseline cohorts for future active longitudinal follow-ups (US DHHS 1987). These longitudinal activities present extensive opportunities for understanding the relationship between risk factors and disease outcome as well as the natural history of disease. Generation and analysis of such longitudinal data is greatly facilitated in countries (e.g., Sweden) where various governmental information systems and surveys can be linked.

11. Technological Advances

Advances in technology have affected the conduct of all surveys. Computer-assisted telephone and personal interviewing have allowed for increasing levels of complexity of survey administration. Errors associated with keying and coding have been replaced by errors associated with programming. The use of these technologies has resulted in the need for longer lead times prior to fielding a study but has reduced the time from the end of data collection to the availability of results.

The increase in electronic as opposed to paper files has greatly expanded the opportunities for linking data from various sources. Ecological or contextual information about the geographic area in which survey respondents live can now be linked to the survey data. This has the advantage of allowing researchers to address different levels of analysis. Survey data can also be augmented with administrative data from mortality files and from health care providers. In addition to reducing survey costs, this often leads to data of improved quality.

12. Methodological Research And Analytic Techniques

The quality of health survey data has been greatly increased by methodological research on survey techniques (Bradburn and Sudman 1979, Fowler 1995, Lessler and Kalsbeek 1992). A major advancement has been the development and application of cognitive methods for questionnaire construction (Sirken et al. 1999). Drawing from the field of cognitive psychology, cognitive research laboratories have been established and can investigate how respondents perceive and answer questions. Another fruitful area of research involves studying the behavior of both interviewers and respondents within the social context of the interview situation (Cannel et al. 1977). A more structured approach to the errors found in health surveys will enhance data quality. The results of this research will lead to improved design that minimizes error but will also lead to ways to adjust for known errors in the analysis and interpretation of results (Jabine 1987).

Advances have also been made in the development of appropriate analytic tools for use with health survey data. These include methods to account for such issues as survey nonresponse and complex survey design. As it is possible to collect data of increasing complexity, it will be necessary to develop the analytic approaches appropriate for the collection methods used (Korn and Graubard 1999, Biemer et al. 1991, Groves and Couper 1998, Rubin 1987).

13. Privacy And Confidentiality

For ethical reasons and in order to obtain high response rates and valid information, most health surveys closely guard the information provided by respondents. In some cases, the requirement to protect confidentiality is legislatively mandated. This is particularly important for health surveys, given the personal nature of the information collected. Confidentiality can also be protected by not releasing data that could identify a respondent. Most survey sponsors subject files that are to be released for public use to rigorous disclosure review. The risk for inadvertent disclosure has increased in recent years. It is no longer necessary to have access to large mainframe computers to utilize survey data, much of which are provided on the Internet or on CD-ROMs. In addition, databases not related to the survey data, but which can be used to identify individuals in the survey data files, are more available and more easily accessible.

It is the potential linking of survey data to these external databases that increases the risk of disclosure, and the risk increases with the amount of information that is available. The ability to link external data to survey responses presents an analytic breakthrough as the utility of survey data can be greatly increased through the appropriate linkages, however, this ability also greatly increases the risk of disclosure especially when the linkages are done in an uncontrolled and inappropriate way. The increased sensitivity to issues of privacy in many countries, especially as related to health care, is affecting how confidential data are being protected. There has been a decrease in the amount of data that can be released as public use files. Other mechanisms are being developed so that access to data can be maximized while protecting confidentiality. The use of special use agreements, licensing and research data centers are examples of these approaches (Journal of Official Statistics 1998).

Bibliography:

- Biemer P P, Groves R M, Hyberg L, Mathiowetz N, Sudman S (eds.) 1991 Measurement Errors in Surveys. Wiley, New York

- Bradburn N M, Sudman S 1979 Improving Interview Method and Questionnaire Design. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

- Cannel C F, Monquis K H, Launent A 1977 A summary of studies of interviewing methodology. Vital and Health Statistics (Series 1, No. 69)

- Edwards W S, Winn D M, Collins J G 1996 Evaluation of 2week doctor visit reporting in the National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics (Series 2, No 122)

- Erickson P, Kendall E A, Anderson J P, Kaplan R M 1989 Using composite health status measures to assess the nation’s health. Medical Care 27(3): 566–77

- Fowler F J 1995 Improving Survey Questions. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Groves R M, Couper M P 1998 Nonresponse in Household Interview Surveys. Wiley, New York

- Idler E L, Angel R J 1990 Self-rated health and mortality in the NHANES I. Epidemiologic follow-up study. American Journal of Public Health 80(4): 446–52

- Jabine T B 1987 Reporting chronic conditions in the National Health Interview Survey: A review of tendencies from evaluation studies and methodological tests. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics (Series 2, 105)

- Journal of Official Statistics 1998 Disclosure limitation methods for protecting the confidentiality of statistical data. Journal of Official Statistics 14: 337–573 (Special issue)

- Korn E L, Graubard B I 1999 Analysis of Health Surveys. Wiley, New York

- Lessler J T, Kalsbeek W T 1992 Nonsampling Error in Surveys. Wiley, New York

- McDowell I, Newell C 1996 Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Monheit A C, Wilson R, Arnett R H (eds.) 1999 Informing American Health Care Policy: The Dynamics of Medical Expenditure and Insurance Surveys, 1977–1996. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

- Moore J 1988 Self proxy response status and survey response quality: A review of the literature. Journal of Official Statistics 4(2): 155–72

- National Center for Health Statistics 1999 Health United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD

- National Center for Health Statistics 2000 International Health Data Reference Guide 1999. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD

- Rubin D B 1987 Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley, New York

- Sirken M G, Herrmann D J, Schecter S, Tourangeau R (eds.) 1999 Cognition and Survey Research. Wiley, New York

- Stewart A L, Ware J E (eds.) 1992 Measuring Functioning and Well-being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Duke University Press, Durham, NC

- United States of America, Department of Health and Human Services 1987 Publication No. (PHS) 92-1303, Series 1, No. 27. Plan and Operation of the NHANES I Epidemiologic Followup Study

- Wilson R W, Druny F 1984 Interpreting trends in illness and disability: Health statistics and health status. Annual Review and Public Health 5: 83–106

- World Health Organization 1948 World Health Organization Constitution in Basic Documents. World Health Organization, Geneva