Sample Comparative Health Care Systems Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Introduction

Each country’s health care system is contained within a singular configuration of culture, history, politics, and economic capacity, and from these derive a specific mode of financing, delivering, and even evaluating health care. Yet, despite the uniqueness of each health care system, all are experiencing similar exogenous pressures, albeit to different degrees, arising from unprecedented developments in science and technology, demographic distributions, and patterns of disease, to name a few. And, despite their differences, many countries are responding to these pressures in remarkably similar ways. As Brown (1998, p. 36) puts it, ‘Everywhere one hears the weary refrain: ‘‘We can no longer afford the [health care] system we have.’’ ’

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

To some scholars these similarities in pressures and responses suggest an impending convergence in health care systems, defined as ‘a certain macro process in which a narrowing of system options takes place’ (Mechanic and Rochefort 1996, p. 242). Mechanic and Rochefort emphasize, however, that convergence does not imply a blurring of social, cultural, and ideological distinctions among nations. Indeed, each nation’s response necessarily builds on ‘preexisting social institutions and professional organizations’ (1996, p. 243). A number of scholars (cited throughout this research paper) have identified a specific kind of convergence in health care: many nations are turning to some type of market reform in order to control expenditures. This trend entails an unusual paradox: many of the ideas on market reform emanate from the United States, and yet the United States remains, not just an ‘exception’ among advanced industrial societies in its commitment to a welfare state in general and to health care in particular (Ruggie 1996), it is also a pariah from the perspective of universal coverage. At present, over 44 million Americans—approximately 18 percent of the population—are without health insurance, and millions more are underinsured. Adding to the paradox of the convergence, it is not altogether clear that the new methods offer a long-term solution to the problem of rising health care costs (Light 1997). For instance, an increase in administrative expenses is frequently associated with the need to assess competitive bids and manage the varieties of insurers and providers in a competitive market. In addition, concern about the consequences of market-based reforms on equity and access may already be diffusing, if not halting, recent innovations.

These inconsistencies in processes and outcomes suggest that the march toward marketization and the convergence it implies may be more apparent than real (OECD 1994, Gray 1998). Jacobs (1998, p. 5), among others, observes that while marketization connotes a direction of change and implies a choice of policy instruments, empirically it can become a ‘highly eclectic venture.’ His study shows that reforms—which introduced provider competition, greater cost-consciousness, and more patient choice—in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and the Netherlands actually resulted in divergence. Contrasting goals among political actors embedded in different institutional systems led to outcomes that were more significant for their dissimilarities than their resemblances.

Focusing on data from the 29 OECD countries and experiences from selected cases, this research paper explores the convergence/divergence debate by examining some of the main changes occurring in health care systems at present and some of the key issues driving change. It argues that convergence may be occurring at the level of interest among governments in experimenting with market-based forms of organizing health care, but whether this development constitutes what Max Weber would call a ‘master trend’ (a dominant movement in social change), sufficient to coalesce other distinctions, is far from clear. For an equally important concurrence is the resort on the part of governments to various types of regulation to mitigate the impact of market mechanisms. Hence, what we are witnessing is an oxymoron of modern society first identified by Karl Polanyi decades ago: planned markets. In general, this thesis also captures the experience of developing countries beyond the OECD, many of which are trying to introduce market reforms, and not only in health care. However, since planned markets require a relatively strong state, developing countries may be hindered in their capacity to harness viable market-based innovations.

2. Financing And Spending: An Overview

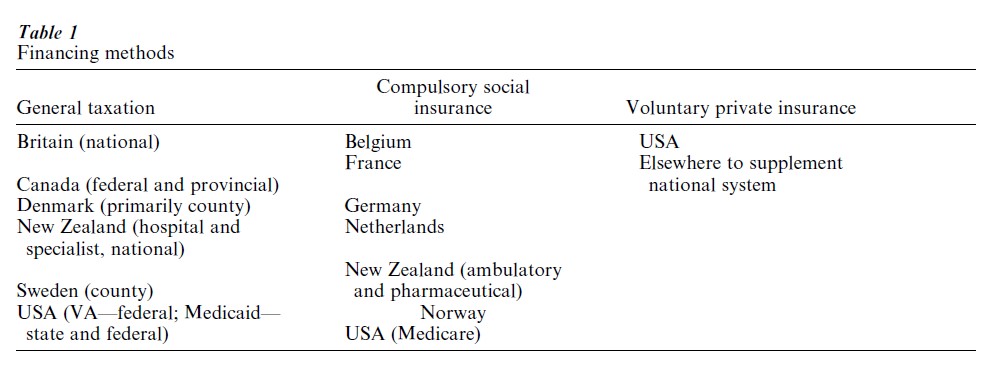

Health care systems are most commonly categorized according to three main methods of financing: general taxation, compulsory contributions to social insurance, and voluntary private insurance or direct payment (see Table 1). Health care systems funded through taxation tend to achieve the highest degree of universal coverage and, in principle, equity in access and provision. Within each category, however, significant differences occur in the delivery of health care services and these may affect patterns of coverage.

For example, Britain, Canada, Denmark, and Sweden all raise funds for health care through general taxation. But Britain considers its system to be a national health service, a concept more commonly associated with socialist countries. The other countries have national health insurance systems. The main difference is that under a national health service, ownership and/or control of the factors of production is public. Ownership of the factors of production in national insurance systems varies, but in general most hospitals are in the public domain whereas physicians consider themselves to be independently employed. Another difference pertains to the degree of centralization. In Canada, the national insurance system is funded by a combination of federal and provincial taxes. Also, the Canadian system is administered by the provinces, the Danish and Swedish systems by counties. While adminstration of the British national health service is decentralized, overall priorities emanate from the central government insofar as local governments have no independent source of revenue. National or social health insurance systems are much more frequent than national health service systems. In most national health insurance systems, unlike in Canada and Scandinavia, financing is based on employer and employee contributions to an insurance fund (Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway); these contributions are compulsory for all employers and many workers. The funds may be administered privately (this is most likely if the funds are closely tied to employer or employee organizations) or publicly. Governments sometimes contribute to the funds as well and invariably set up some contributory mechanism to provide for special groups (such as low income or unemployed individuals). Social insurance systems generally achieve their universality by being tied to social security systems. Ownership of the factors of production varies considerably, but in general there is more private control than in systems funded through taxation.

Voluntary private health insurance is purchased by either employers or individuals or, in some cases, by a combination of the two. While this system predominates in the United States, it occurs in many other countries as a supplement to the national system. Depending on the country, private insurance may cover either private services only or some portion of public services as well.

Most countries house some mix of these models. For instance, in New Zealand hospital and specialist services are funded through general taxation, whereas financial support for ambulatory services and pharmaceuticals derives from an earmarked social security fund. In the United States, the Veterans Administration resembles a national health service and is funded through general taxation; Medicare is a national insurance system for those aged 65 and over as well as for the disabled, and is based on compulsory employer and employee contributions; and Medicaid is an insurance program for the poor funded through general taxation.

Some recent efforts to control rising costs have tinkered at the margins of basic financial arrangements, but none has significantly changed a country’s distinctive modality. Many cost-control efforts have sought to increase the contribution of private payments to overall expenditures. Even though all advanced industrial societies except the United States have ‘national’ systems, there is a considerable range in the public private mix (Ruggie 1996). The term privatization suggests a direction of change away from the state, but actual cases of privatization demonstrate that the process is complex and does not necessarily shed government responsibilities.

Most countries have encouraged an increase in the role of private insurance by, for instance, granting a tax deduction to employers or individuals (Australia, Britain) or reducing the amount of public provision of certain services, leaving the private sector to fill the gap (Canada). Most countries have also increased charges to patients each time they use certain services (including hospital care in Sweden and general practitioners in New Zealand), but these additions tend to be nominal and aimed at enhancing cost consciousness and deterring frivolous or unnecessary use. Efforts to shift financial responsibility invariably introduce not only consumerism and commercialism but also stratification and selectivity. For instance, private insurance companies may discriminate by health status and social characteristics (such as age and class), charging certain individuals more while offering a greater range of services to those who can pay higher premiums. As a result, new government regulations have been deployed to correct these inequities.

For their part, private insurance companies are also engaging in cost-shifting by raising the price of premiums, deductibles, copayments, and so on. Similar increases in recipient contributions to social insurance funds have occurred as well. Some social insurance systems have attempted to increase cost consciousness by offering consumers greater choice among plans (Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden). While this fundamental market principle— choice—has increased competition within health care systems, its impact on costs is dubious because, unlike the predictions of market models of rationality, patients are not inclined to choose less care.

It is difficult to assess the effect of these privatization measures on the overall burden of health care expenditures, because they rarely appear alone. Also, while privatization by definition connotes some form of marketization, what exactly occurs is too variable and vague to be analytically useful. To confuse the issue even more, marketization can occur without privatization (as in Britain). However, just as privatization may in the end not entail a decline in the role of government, so too marketization is sometimes coupled with greater government regulations. Far from being contradictory, this combination may well provide the key to achieving the new triad of goals in health care: efficiency, effectiveness, and equity.

3. Factors Of Production: State vs. Market

There is general agreement among scholars in the field of health policy that market mechanisms alone are not appropriate in matters of health care. Not only are consumers driven by need and not want, but when in need consumers do not exercise rational choice and prefer to spend to their limits (Evans 1999). However, few consumers are free actors in health care: governments and other third-party insurers buffer individual decisions and indeed shape them. What exists in all health care systems, then, are degrees of marketization and regulation, with pendulum-like swings between them reflecting the inevitable difficulty of staying too long on one side. That we are currently witnessing a (re)turn to market-based mechanisms indicates certain shortcomings in government controls, to be sure. But we ought not expect the market to replace the state, simply to stimulate correctives. Markets in health care, and especially those introduced by governments, are bound to be ‘quasi’ at best and reflective of the dominant social values and norms implicit in their construction.

Market forces have been introduced in various areas of the delivery and provision of health care. However, either the introduction of market reforms has been conducted within the framework of government regulations, especially as these pertain to issues of equity and access, or government regulations have been reintroduced when the negative consequences of market mechanisms on equity and access have exceeded acceptable norms.

3.1 Physicans

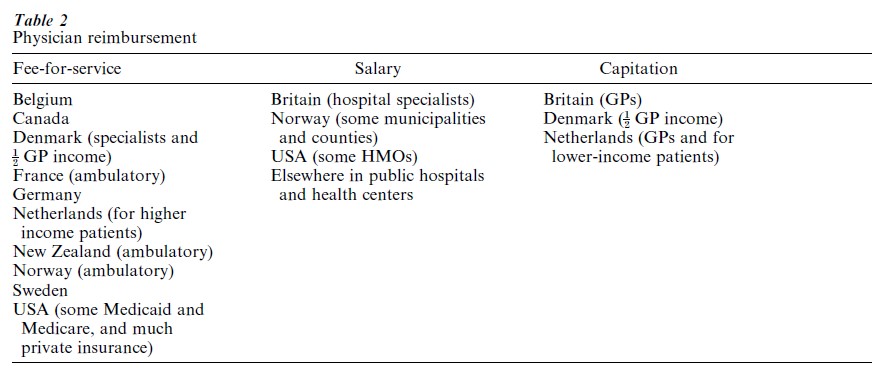

Of the three main methods of reimbursing physicians—fee-for-service, salary, and capitation—fee-for-service is the most open-ended and has been the most difficult to control. Governments (as payers) have attempted either to limit overall increases in fee schedules (as in Canada) or to specify prospective rates for procedures (as in the American Medicare Fee Schedule) (Table 2). In countries with social insurance systems, efforts to exercise these controls are frequently encumbered by corporatist negotiations involving representatives of employers, workers, and physicians. Private insurance companies have found it very difficult to impose reimbursement controls or develop other disincentives to increased utilization of physician services under fee-for-service plans, perhaps because the main competitive edge of private insurance is the greater choice it offers consumers who are willing to pay for higher-priced physician services. Because fee-for-service reimbursement controls encourage physicians to increase the number of patient visits in order to maintain their level of income, governments in Canada and Germany have begun to monitor the volume of physician services.

Physicians tend to be salaried when they work in public hospitals, health centers, or certain types of health maintenance organization (HMO). While salaries are inherently easier to control, they may elicit reduced service provision, especially when specialists also have private fee-for-service practices outside the health care facility. Capitation payments (a specified annual or monthly amount for each patient) commonly accrue to primary care physicians or general practitioners. Although there are outer limits on the number of patients on a physician’s list, in order to control costs there must be strong disincentives to refer patients to specialist physicians or services.

Greater control over physician reimbursement has been facilitated by the introduction of managed care. Managed care is also responsible for ushering in a shift away from fee-for-service reimbursement toward either modified fees (with prospective fee schedules of some sort) or increased capitation if not salaried reimbursement within a physician’s portfolio. Managed care plans rely on primary care physicians to serve as gatekeepers to the system of care, referring patients only when they deem it necessary. Various incentives exist to reward physicians for their efforts, ranging from bonuses in American HMOs to managerial independence among fundholding GPs in Britain. Fundholding GPs are allotted a lump sum payment for their practices and allowed to make all expenditure decisions themselves. Developments such as GP fundholding also represent an attempt to increase provider cost consciousness by making providers purchasers of health care with significant budgetary discretion.

Managed care has also introduced increased forms of competition among providers. Some managed care organizations negotiate contracts with selected providers for their services, encouraging providers to devise attractive offers that promote the goal of ‘value for money.’ Some managed care organizations simply enlist providers who are willing to offer their services for a discount; physicians are motivated to participate in these plans because of the promise of increased volume. In many countries competition is occurring among providers within the public sector, but, while reimbursements levels are affected, the practice is oriented more toward enhancing cost consciousness than achieving any significant reduction in overall expenditure on physician services.

Physicians and patients in the United States have undergone a dramatic and relatively abrupt transition to managed care, but at the same time, this revolution has been stymied by a shortage of primary care physicians. Unlike other countries the government in the United States exercises only weak control over physician supply and distribution, based entirely on monetary incentives. It is expected that the still growing market for managed care will continue to influence physicians to choose primary care as a field of specialization. Meantime, however, experiments are underway (for example, in New York City) in the use of highly trained advanced nurse practitioners as primary care providers. These nurses perform all of the functions of primary care physicians with regard to prescription, referral, and hospital admitting authority, and they are paid at the same rate. They and their employers insist that they are not threatening the livelihood of physicians, simply filling a gap. But their appearance is part of a wider movement to demote the level of skill in certain jobs. In all countries, most types of health care worker are undergoing a deskilling as hospitals cut middle-range positions while hiring lower-skilled replacements, some of whom work only part-time.

Other controls on physicians aim to standardize what in some cases has been wildly divergent practice patterns (Wennberg 1999). Clinical or practice guidelines, also known as medical audits, contain specifications for how physicians should go about treating certain ailments. In most countries these guidelines are developed by the medical profession and monitoring is based on peer reviews, but in other countries (such as the United States) government officials or other interested parties have a hand in the process as well. As protocols for treatment options, clinical guidelines have a dual purpose, for they are also central to efforts to improve quality assurance. Accordingly, in some places they have been extended to include primary care. Finally, in a number of countries, physicians’ expenditures on pharmaceuticals are coming under greater control. Britain and Germany are holding physicians directly responsible for spending over a specified limit.

These and related developments have led to the suggestion that the dominance and authority of the medical profession is declining (Mechanic and Rochefort 1996, Raffel 1997). Certainly, managed care has removed much clinical decision making from the sole domain of the physician and muddied it with administrative rules and budgetary constraints. Further proof derives from the British experience. Having once enjoyed considerable clinical autonomy (especially compared to the United States), physicians in Britain are complaining about the introduction of a planned market with its greater managerial control over medical decision making (Harrison 1995). Alternatively, managed care has enhanced the role of primary care physicians in relation to the secondary sector. Even in countries that already had well-developed primary care services, the incorporation of managed care has strengthened the vertical integration of sectors and placed primary care physicians at the intersection.

There can be little doubt that the heyday of physician dominance over health care is past. But we must look beyond the medical bureaucracy to understand the forces behind this development. For example, better patient knowledge, triggered not only by successful health promotion programs but also by the media and increased access to the Internet, has greatly altered patient–physician relations. Medical authority is also being tested by negative reactions against increasingly more invasive technologies and procedures as patients are turning away from overly medicalized treatments and institutional settings. While we can note change, we ought not jump to conclusions about the endpoint. There is no reason why demedicalization cannot exist alongside a continuation of medical authority. Furthermore, demedicalization has generated greater accountability criteria on the practice of medicine. Accountability requirements have perhaps gone furthest in the United States, where some state and local governments are publishing physican (and hospital) ‘report cards,’ ostensibly to provide consumers with the information they need to make their health care choices. The status of physicians is undoubtedly coming under greater scrutiny, due as much to marketization and its competitively-based principles as to broader social changes in the culture of health care.

3.2 Hospitals

In most countries hospitals consume the greatest portion of health care budgets. By now, various forms of prospective payment systems to hospitals exist in most countries. Prospective payment systems frequently include additional incentives to contain costs, such as allowing hospitals that underspend to keep the difference and average out their costs. Some countries, such as Germany, have prospective per diem rates. Unless they are combined with disincentives to extensive lengths of stay, per diem rates do little to hold down hospital expenditures. Many more countries have already adopted or are shifting to prospective per case rates based on the American Diagnostic-Related Group (DRG) system. In this system each of several hundred categories of diseases and disorders is assigned a numerical value based on service utilization that is then translated into a reimbursement level. Most hospitals responded to the incentives within the DRG system to contain costs by reducing lengths of stay (for example, in Sweden the decline was from an average of 21.3 days in 1985 to 7.8 days in 1995, OECD 1998). The number of hospital beds per population also decreased as a result. However, both of these indicators of reduced hospitalization have occurred in all OECD countries except Korea and Mexico, whether or not countries adopted the DRG system or similar cost containment methods, indicating that a more generalized decline may be occurring in the role of the hospital.

Another prospective payment system, used for years in Britain and Canada, and now being widely adopted elsewhere (France, the Netherlands, Sweden, Finland) is global budgeting on an annual basis. Spending decisions are usually decentralized to the local and even hospital level. In some countries there are strict controls on public sector capital investment in hospitals, sometimes with separate budgeting mechanisms.

A novel form of independent decision making by hospitals has occurred in Britain where hospitals are now self-governing trusts. The move was prompted by the expectation that hospital managers would become more cost conscious if they were responsible for all decisions—purchasing, servicing, delivering, administering, and even paying specialist physicians. Hospitals advertise their services and compete for contracts with, among others, fundholding GPs and local authorities. Similar developments have occurred in Italy and Denmark.

The introduction of cost control measures in hospitals has raised concern about declines in intensity of service and concomitant quality of care. Because of the great diversity among countries in the size of the hospital sector, goals regarding efficiency differ. Countries that are attempting to reduce total hospital output are faced with the challenge of closing hospitals or at least beds that are not being used efficiently (US, Britain). These countries nevertheless join others in striving to encourage hospitals to produce more so as to achieve certain goals, such as reducing waiting times for nonemergency treatments. The ability to regulate hospital costs goes beyond administration, however, for what happens in hospitals is highly dependent on technological advances. Yet, everywhere technology is undergoing contradictory developments.

3.3 Technology: From High To Low

While cause–effect relationships are always difficult to impute, it is safe to say that hospital cost containment has been made possible because of new technologies that have both reduced the risks of certain surgeries and enabled an increase in outpatient surgeries. Paradoxically, rather than expanding megacenters of health care, as in the past, technological innovations may be contributing to the opposite effect. For instance, with the ability to perform more office-based procedures, physicians may be spending less time in traditional hospital settings.

At the same time, reactions against certain technological developments have engendered a number of nonmarket forms of cost containment and a search for less invasive and more personal forms of care, all of which signal new conceptions of what constitutes quality in health care. For example, there has been an exponential increase in the home health industry, which in many countries is contained within the private sector.

In some countries there is also renewed interest in supplementing both primary and secondary care with community care facilities. These provide a range of caregiving services either at home or in clinics, or day centers not only for those recovering from hospital treatment but also for the chronically ill, the mentally ill, and the elderly. Palliative care facilities and hospices are also proliferating to meet the demand for more personal and less technologized care for the dying.

Community care goes hand in hand with a renewed emphasis on preventive medicine, which was first heralded as a cost containment mechanism by the early health maintenance organizations. Insofar as community care, preventive medicine, and related alternative forms of health and healing entail a greater role for patients, both in self care as well as in determining the course of treatment, they also represent a demedicalization of sorts. Nevertheless, as with other evolving relations in health care, we may be witnessing less a replacement of allopathic medicine than a complement to standard modalities.

4. Managing Markets In Health Care

An American economist, Alain Enthoven, first introduced the idea of ‘managed competition’ in health care in 1978. For the American context emphasis was put on the term ‘managed,’ which carried a dual meaning. First, Enthoven was as much an advocate for the development of managed care as for the competition that he felt should occur among managed care organizations based on issues of quality and cost. As his formulations have been imported into other countries, this emphasis has shifted somewhat, but not entirely. Countries with strong primary health care sectors— whether these have been based on general practitioners or community care clinics, or both—have always had the foundations for managed care. For these countries competition among primary, secondary, and tertiary care providers has been more important for enhancing cost consciousness than reducing health care expenditures.

Enthoven also suggested that competition itself should be managed, that is to say regulated, by public agencies who would act as sponsors for consumers. Each sponsor was to be: ‘an active, intelligent collective purchasing agent on the demand side … that creates, develops, administers and enforces the rules of competition in a never-ending effort to root out market failures and to perfect the market’ (1994, p. 1416). Countries with systems of financing based on social insurance funds already had the foundations of such sponsorship. The incorporation of managed competition in these countries (Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand) has primarily enhanced patient choice of fund, although some selective contracting by the funds has also occurred. The consequent increased competition among insurers has raised some predictable problems. In Germany the federal government has introduced risk adjustment schemes to compensate funds that have been negatively affected by the infusion of new patients. Some observers suggest that the equalization and standardization that is resulting may lead Germany toward a single national sickness fund—an odd consequence of managed competition (Freeman 1998). In other words, as new methods of competition are introduced into health care systems, their potentially unsettling consequences are eventually, if not immediately, controlled by new regulatory mechanisms. Even in the United States, proposals for a national Patients’ Bill of Rights promise to reestablish fundamental criteria of justice over the exigencies of competition. Everywhere the result has been to tame market externalities without completely debilitating market mechanisms.

5. Policies, Politics, And People

Given the pressure to expand medical services and the reality of other demands on strained government budgets, countries have been struggling with the dilemma of trying to maintain full and equitable access to high quality health care while at the same time controlling cost increases if not actually cutting expenditure. During the 1980s and 1990s, most countries experimented with some form of market mechanism in order to balance the equation. Interestingly, the effort to contain costs has occurred regardless of level of expenditure. Among those OECD countries actively engaged in health care reform, expenditures on health as a percentage of GDP range from 6.4 in Denmark and 6.9 in Britain to 10.4 in Germany and 14.2 in the United States (OECD 1998). The rate of growth in expenditures has slowed in a number of countries. Many scholars attribute this consequence to the diffusion of a single idea—that the market is best suited to achieve efficiency. Because marketization has occurred regardless of the degree of state vs. market penetration across diverse national settings, some scholars have suggested that a convergence in health care systems is occurring. To some extent countries have accepted new policy instruments cautiously and rationally, learning from each others’ successes and mistakes. But to a larger extent as countries have borrowed ideas and instruments, and adapted these to their own situations, the inevitable tensions between market and state, state and society, professions and politics, values and rationalities have given full play to the rich diversities among health care systems. The current swing toward market solutions to economic problems in health care is limited in its penetration of health care systems, for few countries tolerate for long the negative consequences of market forces on equality and access. Indeed, ‘planned markets appear as an attempt to find more effective administrative instruments, rather than as a conscious or intended surrender of political control over the main objectives of health policy to market forces’ (Saltman and Otter 1995, p. 10).

In the end we must ask, however, whether we are witnessing actual reform of health care systems or something less tangible. If markets are constantly subject to government control, perhaps the underlying goal of reform is cost consciousness and the efficiency it purportedly entails. But beyond the buzzwords, a more profound eventuality is in the offing. If actors are expected to become more aware of the economic consequences of their decisions to utilize health care services, they must also become more attuned to their willingness to forego medical options, for themselves and for others. That health care must be rationed is probably the most difficult realization ecountered by governments and citizens. It rests on the premise that health care is a scarce or at least finite resource, a premise that is hotly debated among medical professionals and ethicists. But as the discussion above has indicated, implicit forms of rationing abound— inability to pay; primary care practitioner ‘gatekeeping’—limited number of professionals; limited number of technologies; queues for treatment–to name but a few. It is unclear how fully these practices are understood to be forms of rationing. Few governments have confronted the issue head on and developed explicit protocols.

The state of Oregon in the United States has one of the only plans specifically denying coverage for certain treatments. But the plan applies only to a population unable to purchase private insurance—Medicaid (poor) recipients. No matter what type of rationing exists, someone has to make the decision about denying access. How a country goes about this task reveals as much about prevailing values and norms as do decisions about financing. The Oregon plan, which on the surface appears to be a Leviathan in a land of individual freedom, was actually the product of considerable grass roots participation. In Britain, government control over the macrolevel of expenditure and priority setting is coupled with confidential case-by-case rationing decisions made by physicians, a process that relies on an unusual level of trust. The persistence of these cultural features of health care systems explains the incomplete successes of market reforms.

Ultimately, however, the story of market-based reform, and the answer to the questions raised about convergence or divergence, rest on an understanding of the role of political institutions in health care systems. For reform to be effective, governments must have the political will to control the demands and behaviors of all relevant actors. But at the same time, for health care to be adequately and justly distributed, governments must marshall citizen involvement in decision making processes in order to construct and legitimate collective goals in health care. This is a universal point, applicable to newly industrializing countries or countries with struggling economies no less than to those discussed in this research paper.

Bibliography:

- Brown L D 1998 Exceptionalism as the rule? US health policy innovation and cross-national learning. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 23(1): 35–51

- Enthoven A 1994 On the ideal market structure for third-party purchasing of health care. Social Science and Medicine 39(10): 1413–24

- Evans R 1999 Health reform: What ‘business’ is it of business? In: Drache D, Sullivan T (eds.) Market Limits in Health Reform: Public Success, Private Failure. Routledge, London

- Freeman R 1998 The German model: the State and the market in health care reform. In: Ranade W (ed.) Markets and Health Care: A Comparative Analysis. Longman, London

- Gray G 1998 Access to medical care under strain: New pressures in Canada and Australia. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 23(6): 905–47

- Harrison S 1995 Clinical autonomy and planned markets: The British case. In: Saltman R B, Otter C von (eds.) Implementing Planned Markets in Health Care: Balancing Social and Economic Responsibility. Open University Press, Buckingham, UK

- Jacobs A 1998 Seeing difference: market health reform in Europe. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 23(1): 1–33

- Light D W 1997 Lessons for the United States: Britain’s Experience with Managed Competion. In: Wilkerson J D, Devers K J, Given R S (eds.) Competitive Managed Care: The Emerging Health Care System. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

- Mechanic D, Rochefort D A 1996 Comparative Medical Systems. Annual Review of Sociology 22: 239–70

- OECD 1994 The Reform of Health Care Systems: A Review of Seventeen OECD Countries. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

- OECD 1998 OECD in Figures. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

- Raffel M W 1997 Dominant issues: Convergence, decentralization, competition, health services. In: Raffel M W (ed.) Health Care and Reform in Industrialized Countries. Pennsylvania State University Press, PA, pp. 291–301

- Ruggie M 1996 Realignments in the Welfare State: Health Policy in the United States, Britain, and Canada. Columbia University Press, New York

- Saltman R B, Otter C von 1995 Introduction. In: Saltman R B, Otter C von (eds.) Implementing Planned Markets in Health Care: Balancing Social and Economic Responsibility. Open University Press, Buckingham, UK

- Wennberg J 1999 Understanding geographic variations in health care delivery. New England Journal of Medicine 340(1): 52–3