Sample Health and Self-Regulation Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Many health conditions are caused by risk behaviors such as problem drinking, substance use, smoking, reckless driving, overeating, or unprotected sexual intercourse. Fortunately, human beings have, in principle, control over their conduct. Health-compromising behaviors can be eliminated by self-regulatory efforts, and health-enhancing behaviors such as physical exercise, weight control, preventive nutrition, dental hygiene, condom use, or accident-preventive actions can be adopted instead. Health self-regulation refers to the motivational, volitional, and actional process of removing such health-compromising behaviors in favor of adopting and maintaining health enhancing behaviors. Health self-regulation encompasses a broad range of social cognitions and behaviors that are subject to developmental changes. This research paper, however, is limited to models that address the current debate within the discipline of health psychology, excluding the larger fields of social and developmental psychology (Baltes 1997, Baumeister and Heatherton 1996, Brandtstadter and Greve 1994, Carver and Scheier 1998).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Health Motivation Factors

Before changing their habits, people need to become motivated. This is seen as a process towards an explicit intention (e.g., ‘I intend to quit smoking this weekend’). Three variables are considered to play a major role in this process: (a) risk perception, (b) outcome expectancies, and (c) perceived self-efficacy (Bandura 1997, Carver and Scheier 1998, Conner and Norman 1996).

Perceiving a health threat seems to be the most obvious prerequisite for the motivation to remove a risk behavior. If one is not aware at all of the risky nature of one’s actions, motivation cannot emerge. Usually, people are aware of some level of risk although the accuracy of their perception may be biased. When it comes to a comparison with similar others, one’s view of the risk is somewhat distorted (‘Compared to others of my age and sex my risk of getting lung cancer is low medium high’). This has become known as the ‘optimistic bias.’ Nevertheless, persons also acknowledge some degree of risk when confronted with objective data. There is a realistic component that keeps the positive illusions in leash. For example, smokers not only know that smoking can cause adverse health in others, they also perceive that they are more at risk themselves for lung cancer and other diseases than nonsmokers.

Risk perception has two aspects: perceived severity of a health condition and personal vulnerability toward it. The first refers to the amount of harm that could occur, and the second pertains to the subjective probability that one could fall victim to that condition. Thus, it has been recommended that people should be informed about the existence of a health risk, and moreover, that they should imagine themselves as possible victims if they do not take the necessary precautions.

Fear arousal is an emotion that can accompany risk perception. Scaring people into health behaviors, however, has not been shown to be effective. In general, initial risk perception seems to be advantageous to put people on track for developing a motivation to change, but later on other variables are more influential in the self-regulation process, such as outcome expectancies, self-efficacy, and behavioral intentions.

People not only need to be aware of the existence of a health threat, they also need to know how to regulate their behavior by understanding the contingencies between their actions and subsequent outcomes. These outcome expectancies are influential beliefs in the motivation to change (Bandura 1997). A smoker may find more good reasons to quit than good reasons to continue smoking (‘If I quit smoking then I will save money’). This imbalance does not lead directly to action but it can help to come up with the intention to quit. The pros and cons represent positive and negative outcome expectancies that are typical in rational decision making. However, such contingencies between actions and outcomes need not be explicitly worded and evaluated, they can also be rather diffuse mental representations, loaded with emotions. Outcome expectancies can also be understood as methods, or means–ends relationships, indicating that people know proper strategies to produce desired effects.

Moreover, the efficacy of such a method has to be distinguished from the belief in one’s personal efficacy to apply the method. Percei ed self-efficacy (Bandura 1997) portrays individuals’ beliefs in their capabilities to exercise control over challenging demands and over their own functioning. Self-regulatory strength (Baumeister and Heatherton 1996) is a similar notion of one’s capacity or stable resource to cope with demands. These beliefs are critical in approaching novel or difficult situations or in adopting a strenuous self-regimen. People make an internal causal attribution when imagining their behavior (e.g., ‘I am certain that I can quit smoking even if my friend continues to smoke’). Such optimistic self-beliefs influence the goals people set for themselves, what courses of action they choose to pursue, how much effort they invest in given endeavors, and how long they persevere in the face of barriers and setbacks. Some people harbor self-doubts and cannot motivate themselves. They see little point in even setting a goal if they believe they do not have what it takes to succeed. Thus, the intention to change a habit that affects health is to some degree dependent on a firm belief in one’s capability to exercise control over that habit.

2. Self-Regulatory Efforts

Changing one’s health behavior is considered to be a difficult self-regulation process. After people have become engaged in a goal they need to prepare action and, later, maintain the changes in the face of obstacles and failures. Thus, goal setting and goal pursuit can be understood as two distinct processes, the latter of which requires a great deal of self-regulatory effort.

The process of self-regulation can be subdivided into sequences such as planning, initiation, maintenance, relapse management, and disengagement although these are not perfectly distinct categories. Plans specify the when, where, and how of a desired action, and carry the structure of ‘When situation S arises, I will perform response R’ (Gollwitzer 1999). People take initiative when the critical situation arises and give it a try. This requires firm self-beliefs to be capable to perform the action. People who do not hold such beliefs see little point in even trying.

The adoption and maintenance of the health behavior is not achieved through an act of will but involves the development of self-regulatory skills and strategies. This embraces various means to influence one’s own motivation and behaviors such as the setting of attainable, proximal subgoals, creating incentives, drawing from an array of coping options, and mobilizing social support. Action control processes include focusing one’s attention on the task, while avoiding attention to distractors, resisting temptations, and managing unpleasant emotions. Perceived self-efficacy is required to overcome barriers and to stimulate self-motivation repeatedly.

Competent relapse management is needed to recover from setbacks. Some people rapidly abandon their newly adopted behavior when they fail to get quick results. When entering high-risk situations (e.g., a bar where others smoke), they cannot resist due to a lack of self-efficacy. The competence to recover is different from the competence to initiate an action (Marlatt et al. 1995). Restoration, harm reduction, and renewal of motivation are serviceable strategies within the context of health self-regulation.

Disengagement from the goal can be evidence for lack of persistence and, thus, indication of self-regulatory failure (Carver and Scheier 1998). But in the case of repeated failures, disengagement or scaling back the goal might become an option which can be adaptive, depending on the circumstances. For example, if the goal was set too high or if the situation has changed and become more difficult than before, it is often not worthwhile to continue the struggle. In the case of health-compromising behaviors, giving up is not a tenable option. Better self-regulatory skills have to be developed and unique approaches to the problem need to be taken. The experience of failure can be a useful learning experience to build up more competence, on the condition that the individual makes a beneficial causal attribution of the episode, and practices constructive self-talk to renew the motivation.

3. Models Of Health Behavior Change

In health psychology, models are built to describe, explain, and predict how people become motivated to change their risk behaviors, and how they become encouraged to adopt and maintain health actions.

3.1 The Transtheoretical Model Of Behavior Change

Stage theorists have made an attempt to consider process characteristics by including the postintentional phase. The Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (DiClemente and Prochaska 1982), for example, has become the most popular stage model. Its main feature is the implication that different types of cognitions may be important at different stages of the health behavior change process. It includes five discrete stages of health behavior change that are defined in terms of one’s past behavior and future plans (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance). For example, at the precontemplation stage, a drinker does not intend to stop consuming alcohol in the future. At the contemplation stage, a drinker thinks about quitting sometime within the next six months, but does not make any specific plans for behavior change. At the preparation stage, the drinker resolves to quit within the next six months. The action stage includes individuals who have taken successful action for any period of time. If this abstinence has lasted for more than six months, the person is categorized as being in the maintenance stage.

The model, which also includes self-efficacy and other relevant features, has been applied successfully to a broad range of health behaviors, with particular success for smoking cessation. However, it has been argued that the notion of stages within this theory might be flawed or circular, in that the stages are not genuinely qualitative, but are rather arbitrary distinctions within a continuous process. Instead, these ‘stages’ might be better understood as ‘process heuristics’ to underscore the nature of the entire model. That is, the model can serve as a useful heuristic that describes a health behavior change process which has not been the major focus of health behavior theories so far. In redirecting the attention to a self-regulatory process, the transtheoretical model has served an important purpose for applied settings. The postintentional, preactional phase (‘preparation’) may be the most challenging stage for researchers and professionals because it is exactly in this phase where an intention is or is not translated into an action—depending on the circumstances. Planning and initiative, but also volatility, hesitation, and procrastination characterize this phase. The identification of stages has been shown to bear important implications for treatment. Interventions have been tailored to communicate stage-matched information to smokers who were in different motivational stages (Dijkstra et al. 1998).

3.2 The Health Action Process Approach

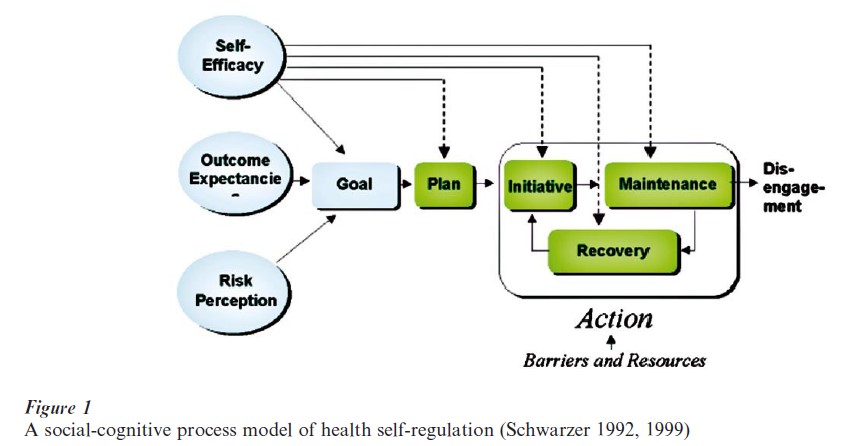

The Health Action Process Approach (HAPA model; Schwarzer 1992, 1999) suggests a distinction between preintentional motivation processes and postintentional volition processes. Within these two phases, different patterns of social-cognitive predictors may emerge (see Fig. 1).

In the initial Motivation phase, a person develops an intention to act. In this phase, risk perception is merely seen as a distal antecedent within the motivation phase. It may include not only the perceived severity of possible health threats but also one’s personal vulnerability to fall prey to them. Risk perception in itself is insufficient to enable a person to form an intention. Rather, it sets the stage for further elaboration of thoughts about consequences and competencies. Outcome expectancies operate in concert with perceived self-efficacy, both of which contribute substantially to the development of an intention, whereas this pattern may change later in the postintentional stage (Schwarzer and Renner 2000).

After goal setting, people enter the postintentional stage or self-regulation phase in which they pursue their goal by planning the details, trying to act, investing effort and persistence, possibly fail, and finally recover or disengage. The guiding principle here is that each substage advances from the previous one and is, in addition, facilitated by perceived self-efficacy. Thus, at each point there are two predictors, namely the successful completion of the previous substage in conjunction with an optimistic sense of control over the next one. Risk perception and outcome expectancies are no longer of much influence when goals have been set and when it comes to predicting actual behaviors. Certainly, there may be various influential factors in the self-regulation phase, but according to the present knowledge, stage progression and self-beliefs appear as the most parsimonious and powerful set of predictors (Bandura 1997, Schwarzer and Renner 2000).

This health behavior change model is regarded as a heuristic to better understand the complex mechanisms that operate when people become motivated to change, when they adopt and maintain a habit, and when they attempt to resist temptations and recover from setbacks. It applies to all health-compromising and health-enhancing behaviors and could be ex-tended to behavior change in general (see Conner and Norman 1996 and Weinstein 1993 for other models).

4. Future Directions

Health self-regulation encompasses a broad range of cognitions and behaviors. Research is needed to identify the key variables and the essential mechanisms that operate in this process. Certainly, different perspectives lead to an emphasis on different variables and mechanisms. A social psychological perspective would underscore social influence and the social context of self-regulation. A life-span developmental perspective would accentuate personal history, life events, as well as gains and losses. The present health psychology view pertains to rather short time periods that are typically involved in coping with addictive behaviors and in thorny cessation attempts. In the last two decades, social-cognitive prediction models had been preferred to explain the mechanisms of health self-regulation. These approaches are being replaced now by stage models that imply a cycling and recycling process of individuals across two or more stages. This advance in the field has led to some difficulties and controversies. One refers to the demand for parsimony because variables become easily inflated. For example, the Transtheoretical model includes five stages and 10 processes. According to the present view, it is suggested to reduce the motivation stage to only three predictors and the self-regulation stage to only two components: stage progression and self-beliefs appear as the most parsimonious set of components. Further elaborations, however, are required and could benefit from other fields, in particular from relapse prevention theory (Marlatt et al. 1995) and self-regulation theories (Baltes 1997, Baumeister and Heatherton 1996, Brandtstadter and Greve 1994, Carver and Scheier 1998, Karoly 1993).

Bibliography:

- Baltes P B 1997 On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: Selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of development theory. American Psychologist 52: 366–80

- Bandura A 1997 Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Freeman, New York

- Baumeister R F, Heatherton T F 1996 Self-regulation failure: An overview. Psychology Inquiry 7(1): 1–15

- Brandtstadter J, Greve W 1994 The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Developmental Review 14: 52–80

- Carver C S, Scheier M F 1998 On the Self-regulation of Behavior. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Conner M, Norman P (eds.) 1996 Predicting Health Behavior: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models. Open University Press, Buckingham, UK

- DiClemente C C, Prochaska J O 1982 Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: A comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addictive Behaviors 7: 133–42

- Dijkstra A, De Vries H, Roijackers J, van Breukelen G 1998 Tailored interventions to communicate stage-matched information to smokers in different motivational stages. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66: 549–57

- Gollwitzer P M 1999 Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist 54: 493–503

- Karoly P 1993 Mechanisms of self-regulation: A system view. Annual Review of Psychology 44: 23–52

- Marlatt G A, Baer J S, Quigley L A 1995 Self-efficacy and addictive behavior. In: Bandura A (ed.) Self-efficacy in Changing Societies. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 289–315

- Schwarzer R 1992 Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors: Theoretical approaches and a new model. In: Schwarzer R (ed.) Self-efficacy: Thought Control of Action. Hemisphere, Washington, DC, pp. 217–42

- Schwarzer R 1999 Self-regulatory processes in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. The role of optimism, goals, and threats. Journal of Health Psychology 4: 115–27

- Schwarzer R, Renner B 2000 Social-cognitive predictors of health behavior: Action self-efficacy and coping self-effi Health Psychology 19(5): 487–95

- Weinstein N D 1993 Testing four competing theories of health protective behavior. Health Psychology 12: 324–33