Sample HIV And Fertility Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

It is widely recognized that HIV had a catastrophic impact on mortality from the early 1990s in much of sub-Saharan Africa, and significant impacts in a few high prevalence countries of South East Asia. The interactions between HIV and fertility are not so well known, but they deserve the special attention of epidemiologists, demographers, and behavioral scientists since they influence our understanding of the epidemic trends and the sexual behavior which underlies this. Limited evidence of the impact of HIV on fertility is available from developed nations with low-level epidemics concentrated in high risk groups such as intravenous drug users, recipients of blood transfusions, and men who have sex with men, but this review concentrates on the situation in African countries with generalized, heterosexually transmitted epidemics. The fertility effects in these populations are much more clear cut, both because the high numbers involved make it relatively easy to collect representative data, and because historically low rates of contraceptive use make it feasible to distinguish between involuntary, biological effects and behavioral responses to the epidemic.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Nature Of HIV And Fertility Interactions

Early speculation on the likely effects of the HIV epidemic on fertility tended to concentrate on change in intentional behavior, and predicted resulting fertility increases. Some authors believed that increases in child mortality might fuel increases in childbearing activity, as parents would want to have many children to ensure that at least a few survived (Caldwell et al. 1992). Others feared that in their quest for safe, uninfected partners, men would seek partnerships with progressively younger girls, thereby lowering the starting age for childbearing. Later writing (e.g., Gregson 1994) has given much more weight to biomedical factors and to unintended consequences of changing behavior.

1.1 Biomedical Factors

HIV lowers fertility directly in several ways, not all of them yet fully understood. Most importantly, it causes spontaneous abortions and stillbirths ( Brocklehurst and French 1998), and in the later stages of the disease women may suffer from amenorrhea ( Widy-Wirsky et al. 1988). In men, it may reduce spermatogenesis (sperm production) ( Krieger 1991), and lower coital frequencies have been reported by couples in which the male partner has begun to suffer from opportunistic infections.

Fertility impairments are also caused by other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), such as syphilis, chlamydia and gonorrhea. HIV is much more prevalent among those who have other STDs, partly because of common behavioral risk factors, partly because HIV-positive individuals are more vulnerable to these infections, but most importantly because the presence of ulcerative STD infections increases the likelihood of HIV transmission ( Fleming and Wasserheit 1999). These direct biological factors affect only a minority of couples in the population, namely those in which one or the other partner is already infected with the HIV virus. Therefore they may not have a large impact on fertility at the population level, but they are important determinants of fertility differentials between HIV positive and HIV-negative women.

1.2 Biosocial Responses To The Epidemic

A range of behavioral responses to the epidemic may alter fertility in the whole population, even though they affect HIV-positive women more than the HIV negative. Studies in Zimbabwe have indicated higher rates of widowhood, higher divorce rates as a result of knowledge or suspicion of HIV infection in either partner, and lower remarriage rates (Gregson et al. 1997). Increased condom use was reported in Uganda, especially in casual relationships, and there was a decrease in extramarital sexual activity ( Kilian et al. 1999) and a postponement of entry into sexual unions by adolescents. These factors would tend to decrease nonmarital fertility. Other behavioral changes in response to the epidemic may tend to cause increases in fertility—for example, in Zimbabwe, some women have chosen to curtail breastfeeding, since it is becoming more widely known that the virus may be transmitted to infants through breastmilk (Gregson et al. 1997). Traditional periods of postpartum abstinence may be shortened to curb the tendency for men to indulge in extramarital affairs—Cleland et al. (1998) showed that in Benin this was more likely to happen when the period of abstinence was lengthy.

1.3 Behavioral Change Consciously Intended To Affect Fertility

There is little evidence that insurance or replacement effects motivate fertility increases: on the contrary, opinion surveys in Tanzania, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe show that the majority believe HIV-infected women should refrain from childbearing in order to limit vertical transmission of the virus and to avoid leaving behind large numbers of orphaned children (Setel 1995, Keogh et al. 1994, Gregson et al. 1997). Followup studies of women in Zaire who were aware of their HIV status have indicated more contraceptive use by the HIV-positive ( Ryder et al. 1991), and higher rates of induced abortion have been reported in some developed countries ( Thackway et al. 1997).

1.4 Changes In Population Structure

Changes in the birth rate can come about not only because of changes in age-specific fertility rates but also because of structural changes in the population. Gregson et al. (1999) showed that HIV-related mortality will tend to make the population structure younger, and with proportionately more women in the peak childbearing ages of 20–29 this would tend to push up the crude birth rate. Similarly, over time, the excess mortality suffered by HIV-positive women with primary or secondary sterility due to coinfection with other STDs would tend to raise the proportion of fecund women in the population and thereby raise the overall birth rate, even if the fertility rates of HIV positive and HIV-negative women did not change. Fecundity could also rise if interventions to treat classical STDs were successful.

2. The Scale Of The Effect Of HIV On Fertility

Empirical evidence for fertility differentials between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women has accumulated from various longitudinal studies. It is summarized below. It is rather more difficult to find unambiguous direct evidence for population level effects, though approximate effects can be estimated by assuming that in the absence of HIV infection all women would experience the fertility patterns currently experienced by the HIV-negative. However, this does not allow for the fact that HIV-positive women may be selected for high levels of other STDs and recent involvement in sexual activity.

2.1 Differences In Fertility Between HIV-Positive And HIV-Negative Women

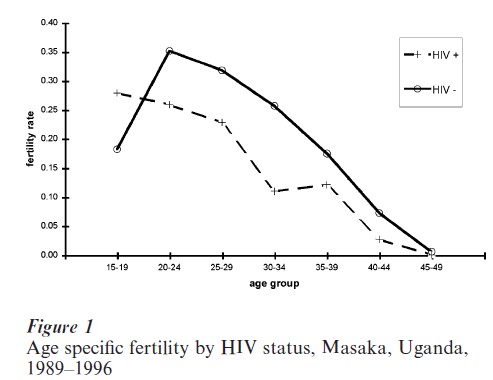

Figure 1 is based on data from the longest running observational study of HIV in a developing country setting, in the Masaka district of Southern Uganda (Carpenter et al. 1997). It shows the typical relationship between fertility in HIV-infected and uninfected women. At ages under 20, HIV-infected women have higher fertility than the uninfected, but at age 20 and over HIV-positive women have significantly lower fertility than the HIV-negative. This is because in the youngest age group those women who have borne children are selected for an early start to sexual activity—virgins are not at risk of childbearing nor are they exposed to the risk of sexually transmitted HIV infection. At later ages, when almost all women are—or have been—sexually active, these selection effects are not so important, and the fertility-reducing effects of HIV, described above, clearly predominate.

2.2 Population Level Effects

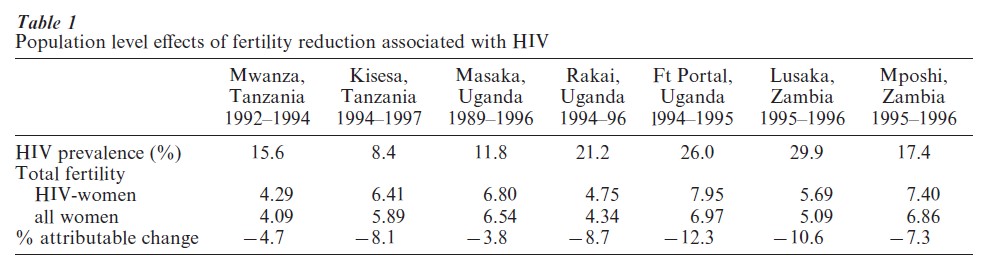

Table 1 (adapted from Zaba and Gregson 1998) indicates the proportionate reduction in fertility attributable to HIV in a number of severely affected populations in Eastern Africa. HIV prevalence in these populations ranges from 8 percent to 30 percent, and fertility in the population as a whole is 4 percent to 12 percent lower than the fertility of HIV-negative women. This represents an average reduction of around 0.4 percent in total fertility for every percentage point increase in HIV prevalence. These observations are all based on studies in populations with low acceptance of family planning—the populations in Table 1 all have contraceptive prevalence rates of less than 15 percent.

There is some indication (Zaba et al. 2000) that fertility differentials between HIV-positive and HIV negative women are not as pronounced in African countries with higher rates of contraceptive use, such as Kenya and Zimbabwe, where over 30 percent of women use modern contraception. However, in these populations fertility had already begun to fall before the HIV epidemic took hold, and it would appear highly likely that the impetus towards lower fertility in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative women would be reinforced by the behavioral changes described above. It would be difficult to ascertain whether fertility would have fallen more slowly in the absence of the epidemic. The ‘attributable change’ statistic is an indicator of the overall effect of differential fertility. It does not take account of the common secular trends for infected and uninfected women.

3. Consequences Of HIV And Fertility Interactions

As a result of the overall fertility reduction in populations severely affected by the HIV epidemic, population growth rates will be even lower than would be expected on the basis of the dramatic increases in mortality. A fall of 10 percent in total fertility would cause a reduction of the order of half a percentage point in the growth rate, making it more likely that some of the worst affected countries could experience periods of negative growth. Since falling fertility causes population aging, this will counter the tendency of HIV-related mortality to make the age structure of these populations even younger.

4. Measurement Of HIV Prevalence In Sentinel Surveillance Populations

One of the more problematic effects of the relationship between HIV and fertility is on the measurement of HIV prevalence. The most widely used source of prevalence data—indeed the source on which all national-level estimates of HIV prevalence are based (US Bureau of the Census 2000)—is sentinel surveillance in antenatal clinics. Since HIV positive women have lower fertility, they will be underrepresented in antenatal clinics, so that the resulting estimates of HIV prevalence underestimate the true extent of infection among women of childbearing age. Where community-based data are available it has been noted that HIV prevalence among adult males is generally lower than that in the female population (UNAIDS 2000), but conventionally the estimates based on surveillance of pregnant women continue to be used to represent prevalence for adults of both sexes. To obtain reliable estimates of HIV prevalence levels in women of childbearing age, one needs to adjust prevalence data collected in antenatal clinics (Zaba et al. 2000), particularly if one seeks to derive estimates of HIV incidence from trends in prevalence in young women. Prevalence estimates for young women may also be affected by changes in the age of sexual debut.

4.1 Trends In Orphanhood And Child Mortality

Reduced fertility in HIV-positive women implies lower effects of HIV on child mortality than were originally anticipated, and fewer orphans will be left behind at the death of an HIV-positive mother than for one who is HIV-negative. At the individual level, many of the fertility reducing factors (such as HIV-associated illnesses or the likelihood of divorce and widowhood) strengthen with duration of infection. As a result, the downward pressure on fertility, and the associated secondary effects on orphanhood and child mortality, will change with the duration of the epidemic, as the balance between women who have been recently infected and those who have been infected for longer periods shifts in favour of the latter. Gregson et al. (1999) have modeled the effect that such trends will have on the number and age distribution of orphans and child deaths.

4.2 Family Planning In The Era Of AIDS

Family planning programmes in sub-Saharan Africa have traditionally promoted hormonal contraception, namely oral contraceptive pills, injectibles, and implants. Barrier methods are regarded with suspicion, as they are considered to be less reliable than hormonal methods and because of their association with commercial and illicit sex. However, effective and systematic use of condoms for disease prevention would also make them highly effective contraceptives. Conversely, an acceptance of condoms for family planning purposes in stable marital unions would destigmatize them and make them more acceptable in other circumstances also. The AIDS pandemic will require a major shift in the contraceptive mix offered by family planning programs and a new willingness to discuss STD prevention in the context of family planning services.

Bibliography:

- Brocklehurst P, French R 1998 The association between maternal HIV infection and perinatal outcome: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 105: 836–48

- Carpenter L, Nakiyingi J, Ruberantwari A, Malamba S, Kamali A, Whitworth J 1997 Estimates of the impact of HIV infection on fertility in a rural Ugandan population cohort. Health Transition Review 7(suppl.): 113–26

- Caldwell J C, Orubuloye I O, Caldwell P 1992 Fertility decline in Africa: A new type of transition? Population and Development Review 18: 211–42

- Cleland J, Ali M, Capo-Chichi V 1998 Post-partum sexual abstinence in West Africa: Implications for AIDS-control and family planning programmes. AIDS 13: 125–31

- Fleming D T, Wasserheit J N 1999 From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: The contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sexually Transmitted Infections 75: 3–17

- Gregson S 1994 Will HIV become a major determinant of fertility in sub-Saharan Africa? Journal of Development Studies 30: 650–79

- Gregson S, Zhuwau T, Anderson R M, Chandiwana S K 1997 HIV-1 and fertility change in rural Zimbabwe. Health Transition Review 7(suppl.): 89–112

- Gregson S, Zaba B, Garnett G 1999 Low fertility in women with HIV and the impact of the epidemic on orphanhood and early childhood mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 13 (suppl. A): S249–58

- Keogh P, Allen S, Almedal C, Temahagili B 1994 The social impact of HIV infection on women in Kigail, Rwanda: A prospective study. Social Science and Medicine 38: 1047–53

- Kilian A, Gregson S, Ndyanabangi B, Walusaga K, Kipp W, Salmuller G, Garnett G, Asiimwe-Okiror G, Kabagambe G, Weiss P, von Sonnenburg F 1999 Reductions in risk behavior provide the most consistent explanation of declining HIV-1 prevalence in Uganda. AIDS 13: 391–98

- Krieger J N 1991 Fertility parameters in men infected with HIV. Journal of Infectious Diseases 164: 464–69

- Ryder R W et al. 1991 Fertility rates in 238 HIV-1 seropositive women in Zaire followed for 3 years post partum. AIDS 5: 1521–7

- Setel P 1995 The effects of HIV and AIDS on fertility in east and central Africa. Health Transition Review 5(suppl.): 179–90

- Thackway S V, Furner V, Mijch A, Cooper D A, Holland D, Martinez P, Shaw D, van Beek I, Wright E, Clezy K, Kaldor J M 1997 Fertility and reproductive choice in women with HIV-1 infection. AIDS 11: 663–8

- United States Bureau of the Census 2000 HIV AIDS Surveillance Data Base. US Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC

- UNAIDS 2000 The Status and Trends of HIV AIDS in the World. Technical report of the Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic Symposium. Durban, 13th International AIDS Conference, July 9–14, 2000

- Widy-Wirski R et al. 1988 Evaluation of the WHO clinical case definition for AIDS in Uganda. Journal of the American Medical Association 260: 3286–9

- Zaba B, Gregson S 1998 Measuring the impact of HIV on fertility in Africa. AIDS 12: S41–50

- Zaba B, Carpenter L, Boerma T, Gregson S, Nakiyingi J, Urassa M 2000 Adjusting ante-natal clinic data for improved estimates of HIV prevalence among women in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 14: 2741–50