Sample Theory Of Lifespan Development Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Lifespan Development, Psychological Aspects

In psychology, the study of human development from infancy until old age has been conducted under the auspices of lifespan psychology. In this research paper, first, a brief historical sketch of the development of lifespan psychology as a field is discussed; second, central constructs and theoretical tenets are presented and illustrated by empirical results; third, methodological issues related to the study of lifespan development are examined; and finally concluding commentary and future perspectives are offered.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

2. Historical Background

Johann Nicolaus Tetens (1777) is considered the founder of the field of developmental psychology in Germany. From this beginning, in Germany development was studied as a lifelong phenomenon. In the USA and in other European countries, such as England, developmental psychology emerged around the turn of the nineteenth century with a strong emphasis on child development. In recent decades, however, a lifespan approach has become more prominent in North America as well, for several reasons. Interdisciplinary synergism is one reason: especially in sociology, which is related to scholars such as Bernice Neugarten or Glen Elder, life course sociology took hold as a powerful intellectual force. A second factor was the emergence of gerontology as a field of study including the search for lifelong precursors of aging. And finally, a third reason may have been the coming of age of several longitudinal studies of child development that had started in the 1920s and 1930s (Baltes et al. 1998).

The first West Virginia Conference on lifespan development—which turned into a series of conferences as well as a book series titled Life-span Development and Behavior (Baltes and Brim, first eds.)—probably marks the emergence of lifespan psychology as a modern psychological theory and field of study (Goulet and Baltes 1970, Thomae 1959). The establishment of lifespan psychology is illustrated by the 1980 Annual Review of Psychology article. In the late 1990s, the continued importance of lifespan psychology is illustrated by contributions to the new Handbook of Child Development and another Annual Review of Psychology article.

3. Lifespan Psychology: Definitions, Metatheoretical Perspectives, And Theoretical Claims

Lifespan developmental psychology or lifespan psychology deals with the study of individual development (ontogenesis) as it extends across the entire life course. Influenced by evolutionary perspectives, neofunctionalism, and contextualism, lifespan psychology defines development as selective age-related change in adaptive capacity (Baltes 1997). In particular, this adaptive capacity involves the acquisition, maintenance, transformation, and attrition in psychological functions and structures. The focus on selection and selective adaptation highlights that development neither is a uniform nor integrated phenomenon across different domains of functioning and across time. This implies that development is conceived as a developing system comprising a multidimensional and multifunctional dynamic. Owing to selective adaptation, different parts of the developing system develop at different rates, in different directions, for different purposes, and may show continuities as well as discontinuities. A further consequence of this definition is that at any point in the lifespan, development is considered as being constituted by gains and losses. With increasing age, the proportion of gains to losses changes in favor of losses. Criteria of what constitutes a gain and what a loss can be of a subjective and objective nature. Losses, in the sense of selection and of crises, are even considered crucial motors of development (Montada et al. 1992, Riegel 1976).

Considering one domain of psychological functioning as an example may help to illustrate this terminological maze. Take for instance, the lifespan development of intellectual functioning. Two main components (multidimensionality) with very different developmental trajectories (multidirectionality) have been distinguished. The two components are the mechanics and the pragmatics of the mind or fluid and crystallized intelligence (e.g., Baltes et al. 1998). The mechanics refer to cognition as an expression of the neurophysiological architecture of the mind as it evolved during biological evolution. The cognitive mechanics are assessed by tasks of reaction speed or inferencing. In contrast, the pragmatics of cognition are associated with the bodies of knowledge available from and mediated through culture. The cognitive pragmatics are operationalized using tests of verbal ability or knowledge. While losses emerge in the mechanics of the mind quite early in development (after 25 years of age), the pragmatics are characterized first by gains and later by stability until quite late in adulthood. The mechanics and pragmatics of the mind also illustrate the notion of the developing system, as they do not operate in isolation but complement each other to support proactive, selective adaptation.

Besides multidimensionality and multidirectionality, the concepts of multifunctionality, equifinality, and multicausality are crucial when taking a dynamicsystem view on lifespan development. Multifunctionality relates to the fact that one and the same developmental change can serve multiple purposes. Research on the concept of dependency provides impressive examples for how in old age, dependency not only implies the loss of autonomy but also the gain of social contact (Baltes 1996). Equifinality in turn refers to the notion that multiple roads can lead to the same developmental outcome. The example of intellectual development illustrates that one and the same behavioral outcome, such as a given cognitive performance, can be attained by using aspects of the mechanics of the mind if one is not used to that cognitive task or it can be accomplished by accessing one’s experience with the task that is by referring to pragmatic aspects of the mind.

Multidimensionality and multidirectionality of development highlight the fact that within one individual there is variability in functioning across different domains. Lifespan psychology, however, is also interested in the intraindividual variability of functioning within one domain across time. This is an aspect of behavior that other subdisciplines of psychology often have devaluated as error variance. Lifespan psychology takes intraindividual variability seriously and considers it as an indicator of the plasticity of development. The notion of plasticity implies that any given developmental outcome is but one of numerous possible outcomes. The search for the conditions, range and limits as well as age-related changes in plasticity is fundamental to the study of lifespan development (Lerner 1984).

Over the years, systematic work on the concept of plasticity necessitated further differentiation. One involved the distinction between baseline reserve capacity and developmental reserve capacity (e.g., Kliegl et al. 1989). Baseline reserve capacity refers to the current level of plasticity available to individuals. For instance, how many words from a list of 20 can a person remember. Developmental reserve capacity specifies what is possible in principle given optimizing interventions. That is, how many words can a person remember after learning a mnemonic technique and practicing this technique for extended periods of time. Such training studies have found that there are impressive intellectual training gains well into old age. Training studies comparing young and old participants, however, have also demonstrated that the training efficiency or developmental reserve capacity is much reduced in old age (Lindenberger and Baltes 1995).

Developmental reserves decline with age. But it is not only the amount of reserves that changes but also the functions that they serve. With increasing age, reserves are less used for growth and more and more for maintenance, recovery and eventually also for the management of loss (Staudinger et al. 1995).

The concepts of plasticity and reserve capacity also highlight the contextual interdependencies of development. Ontogenetic and historical contextualism is another key element of lifespan psychology (Riegel 1976). Contextualism stands in contrast to mechanist or organismic models of development. Lifespan contextualism is related to ecological–contextualist perspectives as well as action-theoretical positions that emphasize the importance of both individual and social–contextual factors in the regulation of development (Smith and Baltes 1999). According to lifespan contextualism, individuals exist in contexts that create and limit opportunities of individual pathways. But individuals also select and create their own contexts.

Contexts evolve according to at least three different logics (Baltes et al. 1980). One is the normative age- graded logic, the second is the history-graded logic, and finally third there is an idiosyncratic or non- normative logic. The age-graded logic refers to those biological and environmental aspects that, because of their dominant age correlation, shape individuals in relatively normative ways. Examples are developmental tasks such as starting school or retirement, or the age-based processes of physical maturation (puberty, menopause). The history-graded logic concerns those variations in ontogenetic development that are due to historical circumstances. Take for instance, the historical evolution of the educational system or the effect of war on ontogenetic development. Finally, the non-normative logic reflects individual–idiosyncratic events of a biological or environmental nature, such as winning the lottery or losing a leg in an accident. All three logics also interact in their shaping of onto- genetic development. In order to understand or predict development, age-graded, history-graded, and person-specific factors have to be taken into account. However, besides contributing to similarities in development, these logics, as Dannefer has argued, also contribute to systematic interindividual variations owing to, for instance, social class.

4. Outlines Of An Architecture Of Human Development

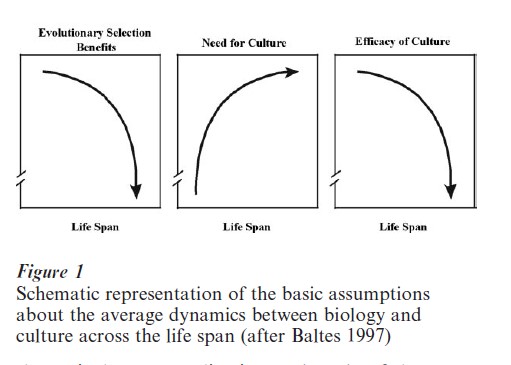

Lifespan contextualism with its three logics leads to the discussion of the two main influences shaping human development: biology and culture. It is in the theoretical conceptualization and study of these two driving developmental forces that lifespan psychology has made the most progress in recent years by formulating the overall biological and cultural architecture of lifespan development (Baltes 1997). This architecture also illustrates the interdisciplinary nature of lifespan development, and how lifespan psychology profits from advances in biology or cultural anthropology. Figure 1 illustrates the three pillars of this architecture. The specific form (level, shape) is not crucial, what is critical is the overall direction and the reciprocal relation between the three functions.

The first element of the tripartite argument derives from an evolutionary perspective. The older the organism, Finch has argued, the less the genome benefited from the genetic advantages associated with evolutionary selection. This assertion is in line with the idea that evolutionary selection has been tied to the process of reproductive fitness and its location in the first half of the life course. This general statement holds true even if indirect positive effects are carried into old age, for instance, though grand-parenting, coupling and exaptation. This age-associated diminution of evolutionary selection benefits was further affected by the fact that in earlier times few people reached old age. Thus, most people died before negative genetic attributes were activated or possible negative biological consequences of earlier developmental events became manifest. The negative consequences of the relative neglect during evolution of the second half of life is amplified by other aspects of biological aging. For instance, biological aging involves wear and tear as well as the accumulation of errors in genetic replication and repair.

The middle panel of Figure 1 summarizes the overall role of culture in lifespan development. Culture, in this context, refers to all psychological, social, material, and symbolic (knowledge-based) resources that humans have produced over the millennia. Among these cultural resources are literacy, cognitive skills, motivational dispositions, physical structures, the world of economics, as well as medical and physical technology. The age-related increase in the need for culture is defined by two aspects. First, the farther we expect human ontogenesis to extend into old age, the more necessary it will be for particular cultural resources to emerge to make this possible. Take, for instance, the increase in life expectancy or educational status during the twentieth century. The genetic makeup did not change during this time. It is primarily through the medium of more advanced levels of culture that people are able to develop throughout longer spans of life. The second part of the argument relates to the age-related biological weakening of the body and the related need for cultural support (material, social, economic, psychological) to generate and maintain high levels of functioning.

The third pillar of the architecture of lifespan development is the decrease in efficacy of cultural resources, that is how much effect a cultural resource has. Despite the acquisition of a variety of bodies of knowledge, the efficiency of cultural factors is reduced, even though large interindividual differences exist in onset and rate of these losses in efficiency. Consider cognitive training interventions as an example of a cultural resource. Research has demonstrated that the older the adult the more time and practice it takes, for instance, to attain the same learning gains. Moreover, in some domains of cognitive functioning and at high levels of performance, older adults may not be able to reach the same level of functioning as younger adults even after extensive periods of training (Baltes et al. 1998). In other words, the efficacy of the cognitive intervention is reduced.

5. Methodological Issues Related To Lifespan Psychology

The search for methods adequate for the study of developmental processes across the lifespan has been a continuing part of the agenda of lifespan researchers (e.g., Lindenberger and Baltes 1995, Magnusson 1998, Nesselroade 1991). One example of methodological innovation is a strategy to examine the scope and limits of plasticity. It is a perennial question of cognitive-aging researchers, for instance, whether aging losses in cognitive performance reflect age-related experiential deficits rather than biological decline. The testing-the-limits paradigm has been developed to answer this question (Kliegl et al. 1989). The testing-the-limits paradigm compresses time by providing for high-density developmental experiences, and by doing so to identify asymptotes of performance potential. These asymptotes, obtained under putatively optimal conditions of support, are expected to estimate the upper range of developmental reserve capacity. Again, this paradigm has been most widely used in research on cognitive development and its plasticity. For instance, in the area of memory functioning, a testing-the-limit approach has been applied. Given young and old participants undergo the same intensive training procedure in a memory technique originally not known to any participant, it was found that after long periods of training and practice, older adults were not able to reach the levels of performance of young adults. These age differences have been much more pronounced than those identified in standard training studies.

Another example is the development of methods that allow the measurement of development including its interindividual differences and contextual variations. Traditionally, the main designs used in developmental psychology were cross-sectional and longitudinal methods. Both methods are characterized by serious flaws, however, when it comes to understanding development. Cross-sectional designs, in which different age groups are compared at one historical point in time, confound chronological age and generational membership. In addition, in a cross-sectional design it is impossible to track individual change trajectories. Longitudinal designs, on the other hand, while providing insight into individual change trajectories, do so only with regard to one single cohort. The challenge to track individual and historical change within one design resulted in the formulation of so-called sequential methods (for history see Baltes et al. 1998). The sequential methods combine sequences of cross-sectional studies (cross-sectional sequence) with successions of longitudinal studies (longitudinal sequence). When both sequences are applied at once exhaustive information about interindividual differences in developmental trajectories, about retest effects, as well as historical change is obtained. As Schaie has demonstrated (1996), cohort effects can be positive or negative, and can concern different age periods to different degrees.

6. Conclusion And Future Developments

Since its formation as a theoretical orientation for the study of human development between infancy and old age, lifespan psychology has advanced our knowledge about human development. A couple of examples may illustrate this point. For instance, we owe it to lifespan psychology that it is now known in which way and to which degree cohort effects can mask age differences (Schaie 1996), or that we have learnt about the reserves of human development, be it in terms of cognitive functioning, self and personality, or social functioning (Staudinger et al. 1995). With its orientation towards understanding developmental plasticity, lifespan psychology has opened new vistas on possibilities of intervention, and has eventually succeeded in making intraindividual variability of functioning a construct of interest to many researchers outside of the field of development (Nesselroade 1991). Finally, it has been lifespan psychology characterized by an orientation towards understanding human development as a dynamic system with functional consequences that has started to further our understanding of the interplay between different areas of psychological functioning, such as cognition, emotion, and motivation, as well as our insight into ecologically relevant and complex constructs such as wisdom and art of life (e.g., Baltes et al. 1998, Labouvie-Vief 1994, Staudinger 1999).

Needless to say, a number of issues remain to be explored. Lifespan psychologists, for instance, have only started to integrate the study of functional aspects of human development with the investigation of microgenetic processes. Projects along these lines have been to ask which are the regulatory processes that allow the aging person to maintain comparatively high levels of well-being and fulfilling lives (e.g., Baltes and Baltes 1990, Brandtstadter and Greve 1994, Heckhausen and Schulz 1995, Staudinger et al. 1995). Within the field of cognitive aging more and more research is oriented towards understanding the microanalytic processes that may underlie the age-related decline in the cognitive mechanics.

Another issue that needs further theoretical and empirical work is the study of the ecology of human development. There is too little systematic work on classifying environments in their effects on human development. And finally the dynamic systems approach borrowed from physics has not yet been explored to its fullest when it comes to understanding human development.

Lifespan psychology does not prescribe the goals of development. Rather, it has taken on the mission to accumulate and disseminate knowledge about which processes and characteristics contribute under which circumstances to the optimization of development. Eventually, it will be this kind of knowledge that every individual may use to compose his or her life in a fulfilling manner.

Bibliography:

- Baltes M M 1996 The Many Faces of Dependency in Old Age. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Baltes P B 1997 On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: Selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of developmental theory. American Psychologist 52: 366–80

- Baltes P B, Baltes M M 1990 Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes P B, Baltes M M (eds.) Successful Aging: Perspecti es from the Behavioral Sciences. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 1–34

- Baltes P B, Lindenberger U, Staudinger U M 1998 Life-span theory in developmental psychology. In: Lerner R M (ed.) Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development, 5th edn., Wiley, New York, Vol. 1, pp. 1029–1143

- Brandtstadter J, Greve W 1994 The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Developmental Review 14: 52–80

- Goulet L R, Baltes P B (eds.) 1970 Life-span Developmental Psychology: Research and Theory. Academic Press, New York

- Heckhausen J, Schulz R 1995 A life-span theory of control. Psychological Review 102: 284–304

- Kliegl R, Smith J, Baltes P B 1989 Testing-the-limits and the study of adult age differences in cognitive plasticity of a mnemonic skill. Developmental Psychology 25: 247–256

- Labouvie-Vief G 1994 Psyche and Eros: Mind and Gender in the Life Course. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Lerner R M 1984 On the Nature of Human Plasticity. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Lindenberger U, Baltes P B 1995 Testing-the-limits and experimental simulation: Two methods to explicate the role of learning in development. Human Development 38: 349–60

- Magnusson D 1998 The logic and implications of a personoriented approach. In: Cairns R B, Berman L R, Kagan J (eds.) Methods and Models for Studying the Individual. Sage, Thousands Oaks, CA, pp. 33–64

- Montada L, Sigrin-Heide F, Lerner M-J (eds.) 1992 Life Crises and Experiences of Loss in Adulthood. L. Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

- Nesselroade J R 1991 Interindividual differences in intraindividual change. In: Collins L M, Horn J L (eds.) Best Methods for the Analysis of Change, 1st edn. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 92–105

- Riegel K F 1976 The dialectics of human development. American Psychologist 31: 689–700

- Schaie K W 1996 Intellectual Development in Adulthood: The Seattle Longitudinal Study. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Smith J, Baltes P B 1999 Life-span perspectives on development. In: Bornstein M H, Lamb M E (eds.) Developmental Psychology: An Advanced Textbook, 4th edn. L. Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 47–72

- Staudinger U M 1999 Social cognition and a psychological approach to an art of life. In: Hess T M, Blanchard-Fields F (eds.) Social Cognition and Aging. Academic Press, New York, pp. 343–75

- Staudinger U M, Marsiske M, Baltes P B 1995 Resilience and reserve capacity in later adulthood: Potentials and limits of development across the life span. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D J (eds.) Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Wiley, New York, Vol. 2, pp. 801–47

- Thomae H 1959 Entwicklungspsychologie [Developmental psychology]. Verlag fur Psychologie, Gottingen, Germany