Sample Children’s Understanding Of Emotions Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Also, chech our custom research proposal writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Theoretical Foundations

A social constructivist theoretical position is taken in this research paper on children’s understanding of emotion, which means that children construct their understanding of emotional experience in the context of cultural beliefs, relationship transactions, and an affordant environment. The child’s cognitive developmental level may be thought of as an organismic constraint on how and with what degree of complexity children construct their understanding of emotion. A functionalist perspective is also evident here in that how we come to understand our emotional experience is rooted in the goals that we have vis a vis our encounters with our environment (Campos et al. 1994). One of the more prominent aspects of western culture’s views of how emotion ‘works’ is the emphasis on cognitive mediation of emotion or appraisal (e.g., Lazarus 1991). This western folk belief about emotions as stemming from one’s thoughts and images derives from an emphasis on emotion as an internal, individual experience as opposed to a number of other cultures’ emphasis on emotion as an interactive experience (Kitayama and Markus 1994). What do we know about children’s acquisition of this belief, namely that emotion results from one’s own cognition (as opposed to deriving from one’s kinship system, from ancestral spirits, or from bodily illness)? Research undertaken by P. L. Harris (Harris 1989) suggests that in the preschool years western children demonstrate in their understanding of others’ experience that the perspective or belief held by the other is significantly involved in determining how the other feels. As they move through middle childhood, children begin to invoke mental factors as well for how to change emotional experience. For example, Harris and Lipian (1989) interviewed children in boarding schools to find out how the children thought they could alleviate negative feelings such as home-sickness and sadness. Older children (age 10) were much more likely to cite such strategies as distraction, focusing on something positive, reinterpreting the situation, and so forth. Younger children (age six) tended to restrict their strategies to suggestions about how to change the situation rather than looking inward to seeing whether and how one might alter one’s internal experience. This greater reliance by the older children on internal, mental states as part of the ‘emotional package’ impacts on several critical features of emotion, among them which cues are used to identify emotions reliably, how emotional-expressive behavior is regulated, and importantly, how to cope with aversive emotions.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Goals play an important role in children’s appraisals of what gives rise to emotions and feelings (e.g., Levine 1995, Wellman and Banerjee 1991). Liking or wanting something or the opposite, not liking or not wanting something, are prominent anchors in how preschool children determine how they or others are likely to feel. Such a goal orientation allows the young child to develop expectations for emotional experience and beliefs about ‘the right way’ to feel. Socializing agents, whether they are parents, peers, or the media, influence what is liked or not liked, and thus affect children’s beliefs about how to feel when they do or do not get what they want. Harris (1995) has also focused on the role that children’s cognitive skills have on their awareness of emotions relative to contexts. He makes an important distinction in children’s understanding of intentional targets of emotions vs. causes of emotions. He contends that children primarily anchor their emotions in appraisal of the object, person, or event at which the emotion is directed (e.g., mad at you, scared of spiders), as opposed to the causal or precipitating event (e.g., a squabble between siblings leads to anger, finding a big spider in one’s bed results in fear). The significance of this idea of intentional targets of emotions as a contextual anchor for children’s understanding of their subjective emotional experience is important theoretically, for it points toward the transactional encounter between person and environment; that is, children construe their emotions as directed at something. Functionalist views of emotion as described earlier emphasize this goaloriented nature of emotion as opposed to other theoretical positions that emphasize the biological causes of emotions.

2. Emotion Understanding And Skills Of Emotional Competence

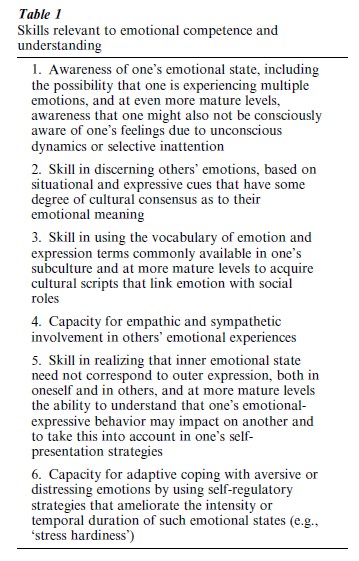

A useful way to examine children’s understanding of emotion is to think of their acquiring a set of skills that facilitate their being able to pursue their goals efficaciously. My use of the term emotional competence is such a construct, and Table 1 lists those skills relevant both to emotional competence and emotion understanding (Saarni 1999). These skills are learned in conjunction with children’s cognitive development and the social contexts in which they are engaged. I shall address children’s understanding of emotion relative to each of these six skills, and in some cases refer the reader to other articles in the encyclopedia that are likely to provide more detailed coverage.

2.1 Understanding One’s Own Emotional Experience

Given that infants’ emotional experience and the self-conscious emotions (e.g., shame, pride) are addressed in Infancy and Childhood: Emotional Development and Self-conscious Emotions, Psychology of, respectively, I shall focus on how older children come to understand that they can have multiple feelings directed at the same target or situation. Young children’s experience of ambivalence has been found to be a sequential process with different appraisals attached to the polarized emotional responses. Research with older school-age children suggests that they have developed the ability to consider at the same time one set of ideas that is at odds with another set of ideas, enabling them to integrate opposite valence emotions (happy and sad) about different targets that co-occur in a situation (e.g., ‘I’m glad I get to live with my dad, but I’m sad about not being able to live with mom too’). In early adolescence simultaneously opposite valence emotions about the same target can be integrated (e.g., ‘I love my dad, even though I’m mad at him right now for not following through on his promise’). In late childhood children also understand that emotions interact with one another; that is, a positive emotion following a negative one can ameliorate the negative feelings one had and vice versa. Similarly, older children report that memories of previous feelings can influence their experience of current emotions. It is not known whether younger children might experience simultaneously two (or more) emotions but can only cognitively construct an explanation about the experience that focuses on one emotion at a time. When children experience an intense emotion, they must also cope with their feelings and the eliciting situation. During this coping process, they may well begin to cognitively construct a more complex system of appraisals about the emotion-eliciting situation or relationship. Finally, younger children (preschoolers to about age seven) scan a situation for its emotional meaning and finding one, stop scanning. Older children do not exhaust the search for further possible appraisals that might yield multiple emotional responses.

2.2 Understanding Others’ Emotional Experience

By late preschool, children can decode the culturally common meanings of prototypical emotional facial expressions, and they have learned as well common situational elicitors of emotions. During this age period they make steady progress in realizing that others have minds, intentions, beliefs, or what has otherwise been referred to as ‘inner states.’ At around 8–10 years of age they understand the need to take into account unique information about the other that might qualify or make comprehensible a nonstereotypic emotional response or a response that differs from how oneself would feel in the same situation. The attributions children apply to their expectations for which emotions are likely can be characterized by three dimensions: stability, which refers to the extent an event will recur; locus, which refers to whether the causes of emotion lie within the person (internal locus and thus stable) or in a context (external locus and thus variable). Another feature is the perceived controllability of the eliciting event. Different combinations of these attributions have been found to characterize different features of children’s understanding of others’ as well as their own emotional experience.

2.3 Understanding Emotional Lexicon And Scripts

Children’s ability to represent their emotional experience through words, imagery, and symbolism of varied sorts allows them to communicate their emotional experiences to others across time and space, and these representations of emotional experience facilitate further cognitive elaboration and comparison with others’ representations about emotional experience. Some of the developments in awareness of our own multiple feelings or in understanding others’ emotions described earlier could not be undertaken without access to a language or representational system for symbolically encoding and communicating emotional experience. Research on early mother–child feeling-state conversations indicates that access to an adult who is interested in one’s feelings may be pivotal to children having opportunities to talk about emotions and acquire a lexicon of emotion vocabulary. Mothers tended to use conversations about feelings as a functional way to guide or explain something to their children, whereas the children were more likely to use feeling-descriptive words simply to comment on their own reaction or observation of another (Dunn et al. 1991). Thus, they were learning to communicate their own self-awareness of feeling states to their mothers, who in turn were likely to communicate meaningfulness to their children by using guiding, persuading, clarifying, or otherwise interpretive feeling-related language. Other research has also documented that if families were characterized as high in frequency of anger and distress expression, the children were less likely to be engaged in discourse about feelings. But if the families were low in frequency of negative emotional expression, then when a negative emotional event did occur for the child, there was a greater likelihood of an emotion-related conversation to ensue between child and parent (Dunn and Brown 1994). Acquisition of emotion-descriptive concepts continues throughout childhood and into adolescence, but little research has examined these older age groups. One way that emotion language develops further in the school-age child and adolescent is evidenced in their greater ability to add variety, subtlety, nuance, and complexity to their use of emotion-descriptive words with others.

2.4 Understanding Empathy And Sympathy

With empathy children affectively share in another’s emotional experience; with sympathy they understand another’s emotional experience but are more detached from it. Some individuals experience vicariously another’s emotion so strongly that it becomes aversive; they tend to focus on alleviating their own personal distress and generally are not likely to show prosocial behavior toward the distressed person. Preschoolers are capable of responding empathically to others’ distress, and what continues to develop in their understanding is what to do if they are to respond prosocially and appropriately. As they learn more subtle cues of emotion, their range for responding empathically or sympathetically is similarly extended. Prosocial Behavior and Empathy: Developmental Processes considers this topic in much greater detail.

2.5 Understanding Of Emotion Dissemblance And Management Of Expressive Behavior

Research has demonstrated that by 10–11 years, children understand that the expression of emotion, whether genuine or dissembled, is a regulated act. At this age they are able to make reference to the degree of affiliation with an interactant, status differences, and controllability of both emotion or circumstances as contextual features that affect the genuine or dissembled display of emotion. However, across all ages, the most common reason cited for when genuine feelings would be expressed was if they were experienced as very intense (and thus less controllable). When children are asked to explain why feelings are not genuinely expressed, four broad categories of motivation are apparent in their responses: (a) to avoid anticipated negative outcomes, (b) to protect one’s self-esteem or to cope more effectively with how one feels, (c) to avoid hurting someone else’s feelings, and (d) to abide by norms and conventions (e.g., rules of etiquette). By school entry children generally understand that how one looks on one’s face is not necessarily how one feels on the inside. They can often provide justifications for how appearances can conceal reality, in this case, the genuine emotion felt by an individual. Many of these justifications included describing the intent to conceal one’s feelings and to mislead another to believe something other than what was really being emotionally experienced. Children younger than six can readily adopt pretend facial expressions, but they are not likely to be able to articulate the embedded relationships involved in deliberate emotional dissemblance. These embedded relationships refer to how the self wants another to perceive an apparent self, not the real self. In other words, by age six children readily grasp that emotional dissemblance has as its basic function the creation of a false impression on others.

2.6 Understanding Of Emotion Regulation And Coping Strategies

Two general patterns have emerged with regard to age: as children mature, they generate more coping alternatives to stressful situations, and they become more able to make use of cognitively-oriented coping strategies for situations in which they have no control. Embedded in both of these age-related patterns is greater cognitive complexity that is associated with becoming older: (a) the ability to appraise accurately when a situation is simply not under one’s control; (b) the ability to shift intentionally one’s thoughts to something else less aversive; (c) the ability to use symbolic thought in ways that transforms the meaningfulness of a stressful encounter or situation (reframing); and (d) very importantly, the ability to consider a stressful situation from a number of different angles and thus consider different problem solutions relative to these different perspectives. As to when these general developmental patterns in coping are clearly in place, it is likely that by 10 years old most children will have a fairly well-developed coping repertoire that includes the emotion-focused strategies of cognitive distraction and transformation. This assumes, of course, that the family lives of these children have been adequately supportive and that harsh traumas have not preoccupied the children’s emotional resources such that inflexibility or dissociative processes have taken hold in the child’s self-and emotion-regulation. In conclusion, children’s understanding of emotion develops in tandem with their exposure to social situations in which emotions are elicited and with their cognitive development. Enhanced emotion understanding facilitates children’s social competence and provides a buffer against pathology, whereas deficits in emotion understanding may function either as precursors to subsequent maladaptive functioning or as outcomes of pathology.

Bibliography:

- Campos J J, Mumme D L, Kermoian R, Campos R G 1994 A functionalist perspective on the nature of emotion. The Development of Emotion Regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 59: 284–303

- Dunn J, Brown J 1994 Affect expression in the family, children’s understanding of emotions, and their interactions with others. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 40: 120–37

- Dunn J, Brown J, Beardsall L 1991 Family talk about feeling states and children’s later understanding of others’ emotions. Developmental Psychology 27: 448–55

- Harris P, Lipian M S 1989 Understanding emotion and experiencing emotion. In: Saarni C, Harris P L (eds.) Children’s Understanding of Emotion. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 241–58

- Harris P L 1989 Children and Emotion: The Development of Psychological Understanding. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Harris P L 1995 Children’s awareness and lack of awareness of mind and emotion. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S L (eds.) Emotion, Cognition and Representation. University of Rochester Press, Rochester, NY, Vol. 6, pp. 35–7

- Kitayama S, Markus H R (eds.) 1994 Emotion and Culture, 1st edn. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC

- Lazarus R S 1991 Emotion and Adaptation. Oxford University Press, New York

- Levine L 1995 Young children’s understanding of the causes of anger and stress. Child Development 66: 697–709

- Saarni C 1999 The Development of Emotional Competence. Guilford Press, New York

- Wellman H M, Banerjee M 1991 Mind and emotion: Children’s understanding of the emotional consequences of beliefs and desires. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 9: 191–214