Sample Defense Mechanisms Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Defense mechanisms are patterns of feelings, thoughts, or behaviors that are relatively involuntary. They arise in response to perceptions of psychic danger or conflict, or to unexpected change in the internal or external environment, or in response to cognitive dissonance (American Psychiatric Association 1994). They obscure or diminish stressful mental representations that if unmitigated would give rise to depression or anxiety. They can alter our perception of any or all of the following: subject (self?), object (other person), idea, or emotion. In addition, defenses dampen aware-ness of and response to sudden changes in reality, emotions and desires, conscience, and relationships with peoples. As in the case of physiological homeostasis, but in contrast to so-called coping strategies, defense mechanisms are usually deployed outside of awareness. Similar to hypnosis, the use of defense mechanisms compromises other facets of cognition.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

General Description Of Defense Mechanisms

Phenomenology and pathophysiology both play an important role in our understanding of disease. Whereas nineteenth century medical phenomenologists viewed pus, fever, pain, and coughing as evidence of disease, twentieth century pathophysiologists learned to regard such symptoms as evidence of the body’s healthy efforts to cope with physical or infectious insult. In parallel fashion, much of what modern psychiatric phenomenologists classify as dis-orders can be reclassified by those with a more psychodynamic viewpoint as homeostatic mental mechanisms to cope with psychological stress.

The use of defense mechanisms usually alters perception of both internal and external reality. Aware-ness of instinctual ‘wishes’ is usually diminished. Alternatively, as is the case with reaction formation, antithetical wishes may be passionately adhered to. Mechanisms of defense keep affects within bearable limits during sudden changes in emotional life, such as the death of a loved one. They can deflect or deny sudden increases in biological drives, such as heightened sexual awareness and aggression during adolescence. Defenses also allow individuals a period of respite to master changes in self-image that cannot be immediately integrated. Examples of such changes might be puberty, an amputation, or even a pro-motion. Defenses can mitigate inevitable crises of conscience (e.g., placing a parent in a nursing home). Finally, defenses enable individuals to attenuate un-resolved conflicts with important people, living or dead. In each case the individual appears to deal with a sudden stress by ‘denial’ or ‘repression.’ But used indiscriminately, these two terms lose their specificity. For example, the denial of the conflict laden realization ‘I hate my father’ might become transformed by defense to: ‘My father hates me’ (maladaptive projection); ‘I love my father so much’ (compromising reaction formation); or ‘I beat my father at tennis’ (adaptive sublimation).

Defense mechanisms involve far more than simple neglect or repression of reality. They reflect integrated dynamic psychological processes. Like their physiological analogues of response to tissue injury—rubor, calor, dolor, and turgor—defenses reflect healthy, often highly coordinated responses to stress rather than a deficit state or a learned voluntary defensive strategy. Thus, a defense mechanism has more in common with an opossum involuntarily but skillfully playing dead than with either the involuntary paralysis of polio or the consciously controlled evasive maneuvers of a soccer halfback.

Implicit in the concept of defense is the conviction that the patient’s idiosyncratic defensive response to stress shapes psychopathology. For example, physicians no longer classify a cough as disease, but as a coping mechanism for respiratory obstruction. There is increasing evidence that choice of defensive styles makes a major contribution to individual differences in response to stressful environments (Vaillant 1992). For example, some people respond to danger or loss in a surprisingly stoic or altruistic fashion, whereas others become phobic (displacement) or get the giggles (dissociation) or retreat into soothing reverie (autistic fantasy). These responses can be differentiated by assigning different labels to the mechanisms under-lying the responses. While cross-cultural studies are still sorely needed, socioeconomic status, intelligence, and education do not seem to be causal predictors of the maturity of an individual’s defenses (Vaillant 1992).

Despite problems in reliability, defenses provide a valuable diagnostic axis for conceptualizing psycho- pathology. By including defensive style as part of the mental status or diagnostic formulation, clinicians are better able to comprehend what is adaptive as well as maladaptive about their patients’ unreasonable behavior. By reframing patients’ irrational behavior in terms of defense mechanisms, clinicians learn to view qualities that initially seemed most unreasonable and unlikeable about their patients as human efforts to cope with conflict.

Taxonomy Of Defense

Unfortunately, there is as much disagreement about the taxonomy of defense mechanisms as about the taxonomy of personality types, but progress is being made. First, adaptation to psychological stress can be divided into three broad classes. One class consists of voluntary cognitive or coping strategies which can be taught and rehearsed; such strategies are analogous to consciously using a tourniquet to stop one’s own bleeding. The second class of coping mechanisms is seeking social support or help from others; such support seeking is analogous to seeking help from a doctor in response to bleeding. The third class of coping mechanisms are the relatively involuntary defense mechanisms. Such coping mechanisms are analogous to depending on one’s own clotting mechanisms in order to stop bleeding.

Anna Freud (1936), Sigmund Freud’s daughter, was the first investigator to introduce a formal taxonomy of defenses. By the 1970s due to the protean and ephemeral nature of defensive mental phenomena, other competing taxonomies arose (e.g., Kernberg 1975, Thomae 1987, Beutel 1988, Lazarus and Folkman 1984).

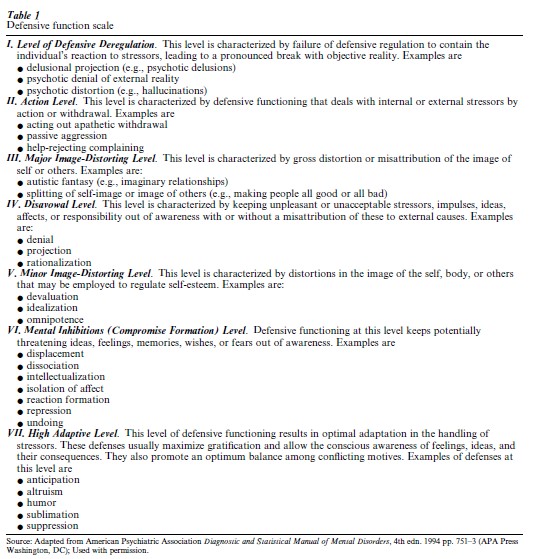

Since the 1970s, several empirical studies have suggested that it is possible to arrange defense mechanisms into a hierarchy of relative psychopathology (e.g., projection (paranoia), to displacement (phobia), to sublimation (art)), and also place them along a continuum of personality development (Vaillant 1977, Perry and Cooper 1989). With the passage of decades, a sexually abused child’s defenses could mature from acting out (e.g., rebellious promiscuity to reaction formation (?joining a convent where sex is bad and celibacy is good) to altruism (as a nun in midlife counseling pregnant teenage mothers). The most recent American diagnostic manual (American Psy-chiatric Association 1994) provides a glossary of consensually validated definitions and arranges defense mechanisms into seven general classes of relative psychopathology (Table 1).

All classes of defenses in Table 1 are effective in ‘denying’ or defusing conflict and in ‘repressing’ or minimizing stress, but the mechanisms differ greatly in the severity of the psychiatric diagnoses assigned to their users and in their effect on long-term psycho- social adaptation. At level I, the most pathological category, are found denial and distortion of external reality. These mechanisms are common in young children, in our dreams, and in psychosis. The definition of such denial in Table 1 is a far more narrow but more specific use of the term than many writers who use the term denial interchangeably with defense mechanisms. Level I defenses rarely respond to simple psychological intervention. To breach them requires altering the brain by neuroleptics or waking the dreamer.

More common to everyday life are the relatively maladaptive defenses found in levels II–V. These categories are associated with adolescence, immature adults, and individuals with personality disorders. They externalize responsibility and allow individuals with personality disorders to appear to refuse help. Such defenses are negatively correlated with mental health. They profoundly distort the affective component of human relationships. Use of such defenses cause more immediate suffering to those in the environment than to the user.

Defenses in these categories rarely respond to verbal interpretation alone. They can be breached by confrontation—often by a group of supportive peers. These maladaptive defenses can also be breached by improving psychological homeostasis by rendering the individual less anxious and lonely through empathic social support, less tired and hungry through rest and food, less intoxicated through sobriety, or less adolescent through maturation.

Level VI defenses are often associated with anxiety disorders and with the psychopathology of everyday life. Level VI include mechanisms like repression (i.e., deleting the idea from a conscious emotion), intellectualization (i.e., deleting the emotion from a conscious idea), reaction formation, and displacement (i.e., transferring the emotion to a more neutral object). In contrast to the less adaptive defenses, the defenses of neurosis are manifested clinically by phobias, compulsions, obsessions, somatizations, and amnesias. Such users often seek psychological help, and such defenses respond more readily to interpretation. Such defenses cause more suffering to the user than to those in the environment.

High adaptive level (VII) defenses still distort and alter awareness of and emotional response to con-science, relationships, and reality, but they perform these tasks gracefully and flexibly—writing great tragedy (i.e., sublimation), for example, is financially rewarding, instinctually gratifying, and sometimes life saving for the author. The ‘distortion’ involved in stoicism (suppression), humor, and altruism seems as ethical and as mentally healthy to an observer as the immature defenses seem immoral and antisocial.

Historical Background

That emotions were significant to humans had been known since ancient times, but it was difficult to develop a concept of defense until psychology could conceptualize the interaction and/or conflict between ideas and emotions. For example, in their influential textbooks the two greatest psychologists of the nineteenth century, Wilhelm Wundt (1894) and William James (1890) discuss a psychology that consisted almost entirely of cognition, not emotion.

Appreciation of the likelihood that it was distortion of ideas and emotions via unconscious mechanisms of defense that led to psychopathology originated with Sigmund Freud (1894). Late in the nineteenth century neurologists had obtained a clearer understanding of the sensory and motor distribution of the nerves. They could appreciate that it was impossible for an individual to have ‘glove anesthesia,’ and certain common paralyses due to neurological damage. Thus, it became possible for neurological science to appreciate that patients could experience anesthesia to pin prick based on their mind’s ‘defensively’ or ‘adaptively’ to distort sensory reality. Trained in both neurology and physiology, Freud was able to appreciate the importance of the phenomena to psychopathology. He suggested that upsetting emotions and ideas could be cognitively distorted in a manner similar to pain and motor behavior. Freud (1894) observed not only that emotion could be ‘dislocated or transposed’ from ideas (by involuntary mechanisms like dissociation, repression, and intellectualization), but also that emotion could be ‘reattached’ to other ideas (by the mechanism of displacement). Later, Freud expanded his theory to suggest that no experience ‘could have a have a pathogenic effect unless it appeared intolerable to the patient’s ego and gave rise to efforts at defense’ (Freud, 1906 1964, p. 276). In other words, much mental illness like coughing and fever might be due to psychological efforts of homeostasis.

Over a period of 40 years, Freud described most of the defense mechanisms of which we speak today and identified five of their important properties. (a) Defenses were a major means of managing impulse and affect. (b) Defenses were involuntary. (c) Defenses could be distinguished from each other. (d) Defenses reflected states, not traits. They were dynamic and reversible. (e) Finally, defenses could be adaptive as well as pathological. Freud conceived of a special class of defense mechanisms—‘sublimations’—that could transmute psychic conflict not into a source of path-ology, but into culture and virtue (1905 1964, pp. 238–9).

From the beginning, however, defenses posed a problem for experimental psychology. First, there is no clear line between character (enduring traits) and defenses (shorter-lived responses to environment). For example, what is the difference between paranoia and projection. There is no clear line between symptoms of brain disease and unconscious coping processes. For example, sometimes one’s obsessions are due to genetic factors alleviated by serotonin reuptake inhibitors and sometimes obsessions are efforts at conflict resolution via the defenses of intellectualization, displacement, and reaction formation. Sometimes the symptoms of neuropathology are wrongly imputed to be due to conflict-driven adaptive aberrations of a normal brain. In addition, behaviors associated with level VII defense can arise from sources other than conflict. For example, altruism can result from gratitude and empathy as well as from conflict.

Thus, in the 1970s both the demands for rater reliability and advances in neuropsychiatry led to psychodynamic explanations for psychopathology falling from favor. As was true in the pre-Freudian era, phobias and paranoia were again attributed more to brain pathology than to adaptive displacement and projection of conflict. Very recently, the limitations of such a purely descriptive psychiatry has led at least American psychiatrists to return defenses to their diagnostic nomenclature (Table 1).

Since the 1970s, several empirical studies well reviewed by Cramer (1991), Vaillant (1992), and Conte and Plutchick (1995) have clarified our understanding of defenses with experimental and reliability studies. This led to a tentative hierarchy and glossary of consensually validated definitions of defense being included in DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994), the American psychiatric manual for diagnosis.

Future Research

A major danger in using psychodynamic formulation as an explanatory concept in psychopathology re-mains unwarranted inference and subjective interpretation. The hierarchy of defenses presented in Table 1 is no more than a system of metaphors, and is not readily susceptible to experimental proof. But several empirical strategies permit placing defense mechanisms on a firmer footing than say handwriting analysis, phrenology, and astrology.

In the future, psychology needs to take advantage of recent advances in neuroscience to achieve further reliability, objectivity, and validity for the study of defenses.

First, we can identify defenses much as we measure the height of mountains that we cannot climb—by triangulation. We can contrast a patient’s symptoms (or a healthy person’s creative product) with his own self-report or mental content and with someone else’s objective report, biography, or medical record. In this way an unconsciously motivated slip of the tongue can be distinguished from a simple mistake, a true paralysis can be distinguished from paresis due to psycho-genic illusion, and a paranoid delusion can be distinguished from true political persecution.

The second method is predictive validity. Phrenology and astrology fail to predict future behavior assessed by independent observers. In contrast, choice of defense mechanisms robustly predicts future behavior (Vaillant 1992). Third, the increasing use of videotape to evaluate complex human process offers the same opportunity for reliability in assessing defense mechanisms (Perry and Cooper 1989).

In the future, there is a need to study defense choice cross-culturally and to clarify the social basis for defense choice and familial transmission. As techniques for brain imaging become perfected, functional magnetic nuclear resonance (FMNR) also offers promise. So does genetics, for there is increasing evidence that personality disorders, which are often characterized by a dominant mechanism of defense, run in families. The demonstration of genetic influences upon defense choice will offer another advance that may make defenses more tangible. Finally, integrating advances in cognitive psychology and evolutionary psychology with advances in our under-standing of neural networks may offer still another potential means of studying defense mechanisms with greater scientific rigor.

Bibliography:

- American Psychiatric Association 1994 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC

- Beutel M 1988 Bewaltigungsprozesse bei chronischen Erkrankungen. VCH, Munich, Germany

- Conte H R, Plutchik R 1995 Ego Defenses: Theory and Measurement. Wiley, New York

- Cramer P 1991 The Development of Defense Mechanisms. Springer Verlag, New York

- Freud A 1936 The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense. Hogarth Press, London

- Freud S 1905/1964 Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In: Strachey J (ed.) Standard Edition. Hogarth Press, London, Vol. 7, pp. 130–243

- Freud S 1906/1964 My views on the part played by sexuality in the etiology of the neuroses. In: Strachey J (ed.) Standard Edition. Hogarth Press, London, Vol. 7, pp. 271–79

- Freud S 1894/1964 The neuro-psychoses of defense. In: Strachey J (ed.) Standard Edition. Hogarth Press, London, Vol. 3, pp. 45–61

- James W 1890 The Principles of Psychology. Henry Holt, New York

- Kernberg O F 1975 Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. Jason Aronson, New York

- Lazarus R S, Folkman S 1984 Stress, Appraisal and Coping. Springer, New York

- Perry J C, Cooper S H 1989 An empirical study of defense mechanisms. Archives of General Psychiatry 46: 444–52

- Thomae H 1987 Conceptualization of responses to stress. European Journal of Personality 1: 171–92

- Vaillant G E 1977 Adaptation to Life. Little, Brown, Boston (reprinted by Harvard University Press)

- Vaillant G E 1992 Ego Mechanisms of Defense: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC

- Wundt W 1894 Human and Animal Psychology. Macmillan, New York