Sample Giftedness And Talent Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Some individuals stand out among their peers because of their remarkable abilities; they are called gifted or talented. What do these two terms mean? How many can be labeled gifted or talented? Are some youngsters much more gifted/talented than others? Are they more at risk developmentally than their average ability peers? What are their major educational needs, and how do school systems answer these needs? These are the major themes covered by this brief overview of a field traditionally named Gifted Education.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Nature Of Giftedness And Talent

Most published definitions of giftedness and/or talent use these two terms as synonyms (Sternberg and Davidson 1986). Yet, most scholars recognize at least implicitly two distinct manifestations of that phenomenon: (a) a natural, nondeveloped form manifested as precocious early development and presented as a ‘potential’, and (b) an adult well-developed form characterized by outstanding achievements in a field of human activity. Gagne (1993) proposed a developmental model that uses this distinction to create differentiated definitions for the two key concepts of giftedness and talent.

1.1 Gagne’s Differentiated Model Of Giftedness And Talent (DMGT )

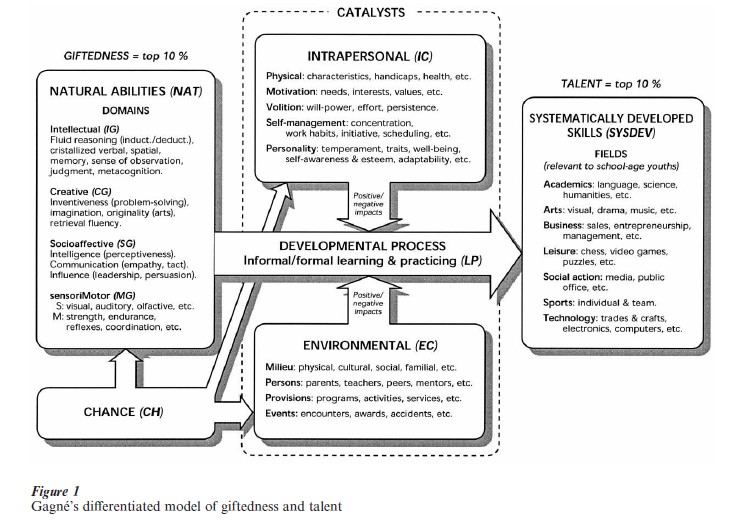

In the DMGT, giftedness designates the possession and use of high natural abilities (called aptitudes) in at least one of four ability domains (see Fig. 1), so that the level of performance places the person among the top 10 percent of same age peers. Talent is the demonstration of systematically developed and trained abilities in any field of human activity at a level such that the individual is among the top 10 percent of peers having had equivalent training. The six components of the DMGT bring together in a dynamic way all the recognized determinants of talent emergence in any field of human activity.

Natural abilities, which have a partial genetic origin, can be observed more directly in young children because environmental influences and systematic learning have exerted their moderating influence in a more limited way. However, they still manifest themselves in older children, even in adults, through the ease and speed with which individuals acquire new skills. The easier or faster the learning process, the greater the gifts. Many laypersons call these gifts ‘natural talent.’ Talents progressively emerge from the transformation of high aptitudes into the well-trained and systematically developed skills typical of a particular field of human activity. Thus, natural abilities act as the raw materials or constituent elements of talents: one cannot become talented without being gifted. However, the converse is not true: it is possible for outstanding natural abilities not to be translated into talents, for instance when intellectually gifted children achieve poorly in school.

The process of talent development manifests itself when the individual engages in systematic learning and practicing (courses, music conservatory, competitive team, etc.); the higher the level of talent sought, the more intensive these activities will be. This process can be facilitated or hindered by two types of catalysts; intrapersonal and Environmental. Among the intrapersonal catalysts, motivation and volition (or persistence, see Corno and Kanfer 1993) play a crucial role in initiating the process of talent development, guiding it, and sustaining it through obstacles, boredom, and occasional failure. Genetic predispositions to behave in certain ways (temperament), as well as acquired personality traits and attitudes, also contribute significantly to the talent development process. The environment manifests its significant impact through four agents, either physical or social. Chance appears in the model as a fifth causal factor; it affects the others in different ways (e.g., the randomness of the genetic endowment for abilities or temperament, the chance of having good parents, accidents, etc.). In summary, talent emerges progressively from natural gifts thanks to a complex choreography between numerous causal influences.

1.2 How Many Are There?

Giftedness and talent are normative concepts. Such concepts define populations that are different from the norm (e.g., obesity, poverty). Good definitions of normative concepts must specify to what extent the target population differs from the norm and what it means in terms of their prevalence. In the DMGT (Gagne 1998), the threshold for both the giftedness and talent concepts is placed at the 90th percentile. That threshold applies to each giftedness domain or talent field; thus, the total percentage of gifted and talented persons probably exceeds 30 percent. This generous minimum threshold is counterbalanced by a system of levels of giftedness and talent. Within the top 10 percent of ‘mildly’ gifted or talented persons, the DMGT recognizes four progressively more selective subgroups, respectively labeled ‘moderately’ (top 1 percent), ‘highly’ (top 1:1,000), ‘exceptionally’ (top 1:10,000), and ‘extremely’ (top 1:100,000).

1.3 Focus

The field of gifted education traditionally has focused on one form of giftedness (intellectual) and one form of talent (academic). There is also some theoretical interest for creative giftedness, although identification procedures rarely include creativity measures. This research paper will respect that tradition and redefine the gifted and talented as intellectually gifted and academically talented (IGAT) students. Intellectual giftedness usually is measured with individual or group intelligence (IQ) tests, whereas academic talent is assessed through grades or standardized achievement tests.

2. Developmental Overview

Except when noted, statements in this section apply best to mildly and moderately IGAT children, who account for 99 percent of that population.

2.1 Personal And Social Development

Most gifted children manifest some form of precocity (e.g., speaking, reading, counting). The degree of precocity is moderately correlated with the level of giftedness. Within the realm of intrapersonal catalysts, the picture is frequently ambiguous. For instance, gifted students do not appear more intrinsically motivated to learn than their average peers (Shore et al. 1991). But there is a tendency for those who achieve well to manifest slightly more persistence. That slight superiority extends to most measures of personal adaptation, whether global ones, like self-administered personality tests, or more specific indicators, like scales for anxiety, depression, or suicidal ideas. IGAT students tend to manifest fewer behavior problems in school, and the incidence of drop outs and delinquents is lower (Neihart 1999). In the case of self-esteem, study results reveal no clear tendency; differences between studies could be associated with the type of educational environment.

Social adaptation refers to friendships, popularity, leadership, and so forth. Socially, gifted youths fare usually as well, sometimes slightly better, than their average peers. Their achievements will often provoke envy, but, most of the time, it is positive envy (admiration, emulation). Are exceptionally gifted individuals more at risk for social or personal adaptation because of the larger gap with their average peers? The scientific literature shows inconsistent results; some studies indicate an increase in the frequency of maladjusted individuals—who still remain a minority (at worst 20–25 percent)—others do not (Norman et al. 1999). Some of these problems could result from inadequate responses to their educational needs.

With regard to environmental catalysts, statistics show clearly that the parents of IGAT students have on average a higher socioeconomic status. According to Herrnstein’s syllogism (Herrnstein and Murray 1994), both the partial genetic inheritance of intelligence and the moderate relationship between IQ and educational attainments could account in large part for that modest over-representation.

In summary, the research base tends to invalidate the ‘nerdy’ stereotypical image of gifted youths. Moreover, it proclaims loudly that IGAT students differ much more among themselves than they do when compared, as a group, with average ability peers.

2.2 Educational And Life Achievements

Intellectual giftedness is synonymous with easier and faster school learning, which leads to academic talent for most of them as long as their progress is not impeded by unfavorable intrapersonal or environmental catalysts. The close relationship between IQ scores and academic achievement is probably the best documented causal relationship in education. IGAT students have much better chances of completing high school, and earning a university degree. As the level of talent increases from moderate to exceptional, the DMGT’s catalysts and practice component play an increasingly important role, especially will-power (Simonton 1994). Nobel prizes, Olympic medals, or international careers in music require intense and prolonged efforts. But such high achievements are extremely rare. In fact, according to the results of Terman’s famous longitudinal study of 1,400 moderately gifted students (Oden 1968), only a minority of IGAT youngsters ever achieve eminence. Other studies with shorter time span confirm that result. This is not surprising since the prevalence of eminent individuals is well below 0.1 percent of the total adult population.

3. Educational Overview

3.1 Educational Needs

Because of their high cognitive abilities, gifted children can easily understand more abstract concepts and more advanced reasoning processes; and they can do that at a much faster pace than average. It is not rare for highly IGAT students to outpace age peers academically by 3 to 5 years. For instance, the US ‘talent searches’ (Assouline and Lupkowski-Shoplik 1997) identify thousands of mathematically precocious students in grades 7 or 8 by administering them the Scolastic Aptitude Test, a test normally used in grade 12 for college admission. Unfortunately, compared with their prevalence in schools, a very small percentage of IGAT students enjoy a school environment that meets their educational needs. The school curriculum targets regular students, and US studies have shown that (a) teachers adjust the normal pace to students close to the 30th percentile, and (b) that the content of school manuals has decreased in density (‘dumbing down’) since the 1980s (Reis et al. 1993). The short-term consequence is recurring boredom due to lack of challenge. The long-term risks are partial loss of interest for school learning and under- developed emotional and strategic skills to overcome obstacles. In summary, IGAT students need a challenging school experience, both in pace and content. Responses recognized as most appropriate differ from the regular curriculum in terms of both content and format.

3.2 A Specific Curriculum: Enrichment

Curricular adaptations specific to IGAT students are grouped under the general concept of enrichment, which can take four major forms—the four Ds. The first, enrichment in Density, corresponds to a faster learning pace, allowing for more content per unit of time. It corresponds to Renzulli’s ‘curriculum compacting’ (see Reis et al. 1993). Not only does it make the learning process more enjoyable, but it also frees time for other enrichment activities. Enrichment in Diversity allows IGAT students to explore subjects outside the regular curriculum of a given grade level (astronomy, genetics, museum visits, history, etc.). Enrichment in Difficulty introduces concepts and explanations well beyond the level planned for regular students. For instance, IGAT students will understand very rapidly the extension of the binary system to any form of non-decimal measurement system. Enrichment in Depth allows students to pursue a personal interest through a long-term research project. Most large-scale enrichment programs in schools combine the four Ds in varying proportions.

3.3 Appropriate Formats: Grouping And Acceleration

In theory, thanks to curricular individualization, teachers should be able to respond to the particular educational needs of every student in their heterogeneous classroom. In reality, it is rarely done. An important US survey of classroom practices (Archambault et al. 1993) revealed that little differentiation is made, except for occasional special activities when IGAT students complete their schoolwork early. That demonstrated lack of individualization confirms the imperative need for ability grouping, either parttime or full-time. Numerous studies have shown the academic and socioaffective benefits of full-time grouping (Kulik 1992), subject to one essential condition: offering these students a truly enriched curriculum. Full-time grouping is rarely used below high-school level, except in special schools. The most popular grouping format in elementary schools, called ‘pull-out classes,’ uses resource rooms where students gather, usually for one or two half-day periods a week. A specially trained teacher supervises enrichment activities, combining the four Ds in various ways to taylor activities to the students’ interests.

The concept of school acceleration encompasses various administrative procedures that allow students either to begin earlier than normal or to progress faster through the grade levels. It includes, among others, grade skipping, covering in one year the curriculum of two grade levels, early entrance to school, credit by examination, and radical acceleration (skipping three years or more). Because it is made possible by intensive enrichment in density, it should be considered a true form of enrichment. Acceleration is undoubtedly the most controversial of all format prototypes. The major fear is the personal and social maladjustment of younger students among older peers due to insufficient maturity. Yet, hundreds of evaluative studies have shown little factual support for that fear (Southern and Jones 1991). When school acceleration is carefully planned and implemented, with appropriate follow-up, the large majority of students adapt very well to their new academic and social environment. But, in spite of compelling scientific evidence for its effectiveness, parents and educators alike remain very reluctant to choose it.

4. Conclusion: The Politics Of Gifted Education

Worldwide, IGAT students remain the most underserved of all special school populations. Compared with the millions of dollars spent by ministries of education for all forms of disabling conditions, gifted education receives almost no direct subsidies. Advocates for these children face many objections: fear of elitism, fear of increasing the gap between the highest and lowest achievers, the need to prioritize those at risk, feelings that intellectually gifted students will succeed anyway. The accusation of elitism is based on the already mentioned observation that IGAT students come disproportionately from affluent families; but the disproportion in percentages conceals the fact that, in terms of numbers, many more IGAT students belong to families with average or below average socioeconomic status. Moreover, why should fast learners be denied an appropriate learning environment because of their social origin? As stated in the UN Bill of Rights of children, all children have a right to an education that will foster the maximum development of their abilities and personality.

Bibliography:

- Archambault Jr F X, Westberg K L, Brown S W, Hallmark B W, Emmons C L, Zhang W 1993 Regular Classroom Practices with Gifted Students: Results of a National Survey of Classroom Teachers. The National Research Center of the Gifted and Talented, Storrs, CT

- Assouline S G, Lupkowski-Shoplik A E 1997 Talent searches: A model for the discovery and development of academic talent. In: Colangelo N, Davis G A (eds.) Handbook of Gifted Education, 2nd edn. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, pp. 170–9

- Corno L, Kanfer R 1993 The role of volition in learning and performance. In: Darling-Hammond L (ed.) Review of Research in Education. American Educational Research Association, Washington, DC, pp. 301–41

- Gagne F 1993 Constructs and models pertaining to exceptional human abilities. In: Heller K A, Monks F J, Passow A H (eds.) International Handbook of Research and Development of Giftedness and Talent. Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 69–87

- Gagne F 1998 A proposal for subcategories within the gifted or talented populations. Gifted Child Quarterly 42: 87–95

- Herrnstein R J, Murray C 1994 The Bell Cur e: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. Free Press, New York

- Kulik J A 1992 An Analysis of the Research on Ability Grouping: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. The National Research Center of the Gifted and Talented, Storrs, CT

- Neihart M 1999 The impact of giftedness on psychological wellbeing: What does the empirical literature say? Roeper Review 22: 10–17

- Norman A, Ramsay D, Martray C, Roberts J 1999 Relationship between levels of giftedness and psychosocial adjustment. Roeper Review 22: 5–9

- Oden M H 1968 The fulfilment of promise: 40-year follow-up of the Terman gifted group. Genetic Psychology Monographs 77: 3–93

- Reis S M, Westberg K L, Kulilowich J, Caillard F, Hebert T, Plucker J, Purcell J H, Rogers J B, Smist J M 1993 Why not Let High Ability Students Start School in January? The Curriculum Compacting Study. The National Research Center of the Gifted and Talented, Storrs, CT

- Shore B M, Cornell D G, Robinson A, Ward V S 1991 Recommended Practices in Gifted Education: A Critical Analysis. Teachers College Press, New York

- Simonton D K 1994 Greatness: Who Makes History and Why? Guilford Press, New York

- Southern W T, Jones E D (eds.) 1991 The Academic Acceleration of Gifted Children. Teachers College Press, New York

- Sternberg R J, Davidson J E (eds.) 1986 Conceptions of Gifted- ness. Cambridge University Press, New York.