Sample Psychology Of Recognition Memory Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Recognition memory is usually used to refer to both a memory measurement and a memory process that occurs in this measure of memory. When discussing recognition memory as a memory measurement, the difference between a recognition memory test and other memory tests such as recall tests can be easily distinguished. Recognition tests also produce certain effects that are particular to the processes underlying recognition memory. Even though the nature of these processes is very complicated, some models of recognition memory have nonetheless been proposed (see, for example, Raaijmakers and Shiffrin 1992). In this research paper, these two characteristics of recognition memory are examined in more detail.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Recognition Memory As A Memory Test

1.1 The Nature Of A Recognition Memory Test

In a recognition memory experiment, to-be-remembered items (also called target items) are presented to subjects. An item may refer to a nonsense syllable, a word, a number, a picture, and so on. In such tasks, subjects are given a recognition memory test after exposure to such items.

There are basically two types of recognition memory tests. In a yes/no recognition memory test, a subject is presented a series of items one at a time. The subject is then asked to say ‘yes’ or ‘old’ if the subject thinks the current item is a target item, and ‘no’ or ‘new’ if the subject thinks it does not qualify as a target one (nontarget items are called distractor items).

This type of a recognition memory test is similar to the sort of true/false test often encountered in school examinations. Another type of recognition memory test is a forced-choice test. In a forced-choice test, the subject is shown two or more items at a time. One of the items is usually a target item and the others are distractor items. In this type of recognition memory test, the subject is asked to pick out the target item from a set of items. If the subject is shown three items at a time, for example, it is called a three-alternative forced-choice test.

As such, the forced-choice test is similar to multiplechoice tests often encountered in school examinations. Of course, many additional variations on recognition memory tests may be considered. For instance, in addition to judging whether an item given on a recognition memory test is a target item or a distractor item, a subject may be asked to give a numerical confidence rating consisting of the range of, for example, 1 (least certain) to 5 (most certain), to indicate how certain the subject is that the judgment is correct.

In order to develop a better understanding of recognition memory tests, it is worthwhile contrasting them with other popular forms of memory test, such as the aforementioned recall tests. In recall tests of memory, a subject is asked to reproduce or generate all the items that had been presented during an earlier study phase. Thus, the basic difference between recognition and recall test procedures is that in a recognition memory test, subjects are given the target and distractor items during the test, whereas in a recall test, the subjects are given instructions to reproduce or generate the items without displaying them.

One of the important differences is that, in general, the subjects can recognize items in a study list much better than they can recall them. In fact, if the subjects are first given a recall test and then given a recognition memory test, it will be usually found that they can recognize many items that they were unable to recall.

1.2 Signal Detection Theory And Performance On A Recognition Memory Test

In a recognition memory test, instead of being assumed that subjects either memorize target items or don’t memorize them, it is assumed that the subjects judge as the target items on something like level of familiarity which varies in memory strength. When an item can be retrieved more readily than the other items, it will be said that the item is at full strength.

The memory strength of a test item is thought of as the degree of its familiarity in long-term memory (LTM). The stronger the test item is in LTM, the more familiar it will be.

To illustrate the assumption, one recognition memory experiment will be considered. Assume that a list of items is given to two groups of subjects, followed by a yes/no recognition memory test. The subjects are tested with a mixed sequence of target and distractor items one at a time. Prior to the recognition memory test, one group of subjects (called a guessing group) is instructed to say ‘yes’ if they think an item was on the list, and ‘no’ if they think it is a distractor item. Guessing is permitted in this group when the subjects receive a recognition memory test. The other group of subjects (called a strict group) receives the same instruction as the guessing group except the guessing instruction. The subjects in this group are instructed not to make a guess when they judge whether an item given on a recognition memory test is a target item or a distractor item. The subjects in the guessing group will of course use guessing strategies. So the results may show that the subjects in the guessing group will pick up more target and distractor items than those in the strict group. The results mean that the subjects in the guessing group judge the target and distractor items on a higher level of familiarity than those in the strict group. However, as can be seen, performance on a recognition memory test in the guessing group may be very similar to that in the strict group.

The signal detection theory which originates with the study of auditory detection tasks (see Green and Swets 1966) and has been applied to recognition memory explains the results of this experiment clearly. The signal detection theory enables researchers to estimate the amount of information stored in LTM on which subjects’ judgments on a recognition memory test are based.

The signal detection theory assumes that the subjects estimate the probabilities that a test item came from the distributions for target and distractor items, respectively, on the basis of its memory strength (or familiarity).

In a typical yes/no recognition memory test, there are four cells that can occur in combination with a subject’s ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses and target-distractor items. First, the item is a target item and the subject says ‘yes’; this is the correct response and is called a hit. Second, the item is a target item but the subject says ‘no’ to it; this is not the correct response and is called a miss. Third, the item is a distractor item and the subject says ‘no’; this is the correct response and is called a correct rejection. Fourth, the item is a distractor item but the subject say ‘yes’ to it; this is not the correct response and is called a false alarm.

These four cells are not independent. As shown above, the hit rate and the miss rate mean the response rates to the target items and the false alarm rate and the correct rejection rate mean the response rates to the distractor items. When the hit rate is known, the miss rate can be understood automatically. Similarly, when the correct rejection rate is known, the false alarm rate can be understood. Generally, the hit rate and the false alarm rate are referred to on recognition memory.

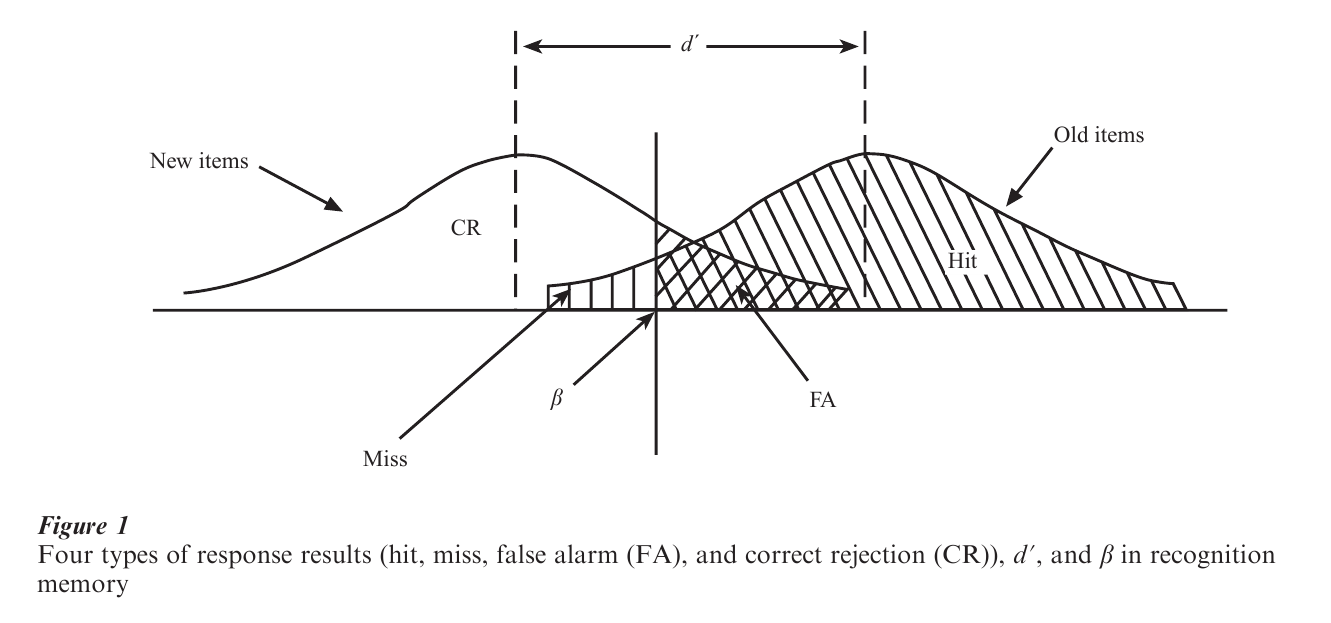

Figure 1 shows both a relationship between the distributions of memory strength for target and distractor items and four cells in a yes/no recognition memory test. Figure 1 shows that the distributions for target and distractor items on the basis of their memory strength represent normal curves and that the mean strength of the target items is usually higher than that of the distractor items.

The distance between the means of the distributions for target and distractor items is called d (called d-prime). More precisely, the d´ value is obtained by dividing the difference between the two means by the common standard deviation of the distributions. We can easily get the d´ value from some publications (e.g., Elliot 1964, Hochhaus 1972). When the d´ value increases, the subject will discriminate between target and distractor items easily. When the d´ value is small, the subject will find it difficult to discriminate between two sets of items.

In addition to the d´ value, there is another value called β (beta). The β value means the level of the criterion strength on which the subject bases the decision. When the d´ value remains constant and the β value goes up (e.g., the β value moves to the target distribution), both hit rate and false alarm rate go down. When the d´ value remains constant and the β value goes down (e.g., the β value moves to the distractor distribution), both hit rate and false alarm rate go up. When the d values are assumed to be the same, the β value in the guessing group stated earlier may be very low and the β value in the strict group may be very high. Figure 1 shows one example of d´ and β values on recognition memory. As can be seen, the d value is referred to recognition accuracy which means the strength difference between target and distractor items in LTM and the β value is referred to as decision criterion. The subject evaluates the memory strength difference between target and distractor items on the basis of decision criterion.

1.3 Some Effects In Recognition Memory

Some effects have been demonstrated in recognition memory, which are referred to as the mirror effect and the context effect. These effects in recognition memory are explained in brief.

First, there is a strong regularity of recognition memory called the mirror effect (see Glanzer and Adams 1985). The mirror effect refers to the regularity of recognition memory in which the type of items that is relatively easy to recognize as old when old is also relatively easy to recognize as new when new. Glanzer and Adams (1985) analyzed a total of 80 experimental findings with several different classes of items and found that performance on new items from each class is correlated with performance on the corresponding classes of old items.

Second, subjects can usually recognize target items better than they can recall them. However, in such test circumstances as recognition memory is measured under the changes in the context between study and test, it will be found that the subjects fail to recognize target items. It is known as the context effect in recognition memory. The context effect in recognition memory shows that even recognition memory depends on the relation between the context at the time of the study and at the time of its test.

2. Retrieval Processes In Recognition Memory

As stated earlier, recognition and recall are usually used to refer to not only memory measurements, but also memory (or retrieval) processes which occur in these memory measurements. There have been hot controversies about how retrieval processes in recognition and recall are similar and different. That question is very difficult to answer and is still controversial (Brown 1976, Tulving 1983).

Generally speaking, recognition memory seems to be easier than recall. Subjects who receive a recognition memory test only discriminate between target and distractor items, even though they do not know the target items clearly. There are some reasons why recognition memory seems to be easier than recall. According to a classical threshold model of recognition memory, the level of the discriminative threshold in recognition is thought to be higher than that in recall. According to the two-process model of recall (Kintsch 1970), recognition memory and recall involve different retrieval processes. Recall involves an extra search (or generate) process in addition to a recognition (or decision) process.

2.1 One-Process Models Or Two-Process Models In Recognition Memory

How about retrieval processes in recognition memory? Recognition memory can usually be referred to by two types of models, one known as one-process models and the other known as two-process models.

One-process models include the Search of Associative Memory (SAM) model proposed by Gillund and Shiffrin (1984) and the Hintzman (1988) model. They assume that recognition judgments are based on the target item’s familiarity involving a single retrieval (search-like) step. Two-process models include the Atkinson and Juola (1974) model and the Mandler (1980) model.

They assume that the retrieval processes in recognition memory are the result of two processes: familiarity and search. For example, Atkinson and Juola (1974) carried out response time experiments from well-learned lists. They obtained the results that items with high or low familiarity values are associated with a fast response of a target item or a fast response of a distractor item, respectively, whereas items with intermediate familiarity values are associated with a slower search process to judge whether an item is a target item or a distractor item. This search process is generally supposed to be slower than the familiarity-based process in the two-process models of recognition memory. The controversies about whether there is a search process in recognition memory are still continuing.

2.2 Recognition Memory With And Without Recollective Experiences

In recent years, there has been considerable interest in comparing performance on a task that does not require conscious or intentional recollection of previous experiences with performance on a task that requires it. A recognition memory test is known as one of the tests that requires conscious recollection of previous experiences. However, Gardiner (1988) assumes that recognition memory may entail two processes concerning recollective experiences: one is a process with recollective experiences and the other is a process without recollective experiences. These two processes are related to differences in subjective experiences.

In a recognition memory test, when recognizing each item, subjects are instructed to indicate whether they are able consciously to recollect its prior occurrence in the study list (called ‘remember’) or whether they recognize it on some other basis (called ‘know’). The results show that a few independent variables, such as levels of processing (deep vs. shallow processing), generating vs. reading target items, and divided vs. undivided attention, have been found to influence ‘remember’ recognition and to have little effect on ‘know’ recognition. For example, performance on semantic processing was better than that on shallow processing in ‘remember’ recognition. However, performance on semantic processing was the same as that on shallow processing in ‘know’ recognition.

The measures of a ‘remember’ judgment and of a ‘know’ judgment are introduced by Tulving (1985), according to which conscious recollection or ‘remembering’ is a by-product of retrieval from the episodic memory system. Feelings of familiarity or ‘knowing’ are characteristic of retrieval from the semantic memory system. Using ‘remember’-‘know’ judgments in recognition memory, it may be possible to examine retrieval processes in recognition memory and memory systems.

Bibliography:

- Atkinson R C, Juola J F 1974 Search and decision processes in recognition memory. In: Krantz D H, Atkinson R C, Luce R D, Suppes P (eds.) Contemporary Developments in Mathematical Psychology. Freeman, San Francisco, CA, Vol. 1

- Brown J (ed.) 1976 Recall and Recognition. John Wiley & Sons, London

- Elliot P B 1964 Tables of d . In: Swets J A (ed.) Signal Detection and Recognition by Human Observers. Wiley, New York

- Gardiner J M 1988 Functional aspects of recollective experience. Memory and Cognition 16: 309–13

- Gillund G, Shiffrin R M 1984 A retrieval model for both recognition and recall. Psychological Review 91: 1–67

- Glanzer M, Adams J K 1985 The mirror effect in recognition memory. Memory and Cognition 13: 8–20

- Green D M, Swers J A 1966 Signal Direction Theory and Psychophsics. John Wiley and Sons, New York

- Hintzman D L 1988 Judgments of frequency and recognition memory in a multiple-trace memory model. Psychological Review 95: 528–51

- Hochhaus L 1972 A table for the calculation of d and β. Psychological Bulletin 77: 375–6

- Kintsch W 1970 Models for free recall and recognition. In: Norman D A (ed.) Models of Human Memory. Academic Press, New York

- Mandler G 1980 Recognizing: The judgment of previous occurrence. Psychological Review 87: 252–71

- Raaijmakers J G W, Shiffrin R M 1992 Models for recall and recognition. Annual Review of Psychology 43: 205–34

- Tulving E 1983 Elements of Episodic Memory. Oxford University Press, New York

- Tulving E 1985 Memory and conscionsness. Canadian Psychology 26: 1–12