Sample Psychological And Social Aspects of Disability Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Disability can be conceptualized as activity limitations resulting from pathological and biomedical factors such as inflammation of the joint, brain lesion, age, or sensory impairment. However, there is evidence that psychological and social factors can predict and possibly influence disability unexplained by underlying pathophysiology. In addition to the definition, prevalence, and measurement of disability, this research paper examines explanatory models, psychological and social predictors and consequences of disability, as well as the possibility of reducing disability and its effects through psychological interventions.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Term ‘Disability’

Disability is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in their International Classification of Impairment, Disability and Handicap (ICIDH) model as ‘any restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being’ (WHO 1980). The ICIDH model proposes that disability is the result of impairment and that disability may result in handicap. Impairment is ‘any loss, abnormality or failure of psychological, physiological, or anatomical structure or function’ and is the direct result of an underlying disease or disorder. Handicap is ‘a disadvantage resulting from impairment or disability, that limits or prevents the fulfillment of a role that is normal for that individual’ (WHO 1980, pp. 27–9). So, for example, an individual who experienced a stroke (disorder) might have restricted leg functioning (impairment), resulting in limitations in mobility (disability), and therefore be unable to continue to work (handicap).

However, disability is a widely used term both in everyday speech and by individuals in academic and applied disciplines, in addition to medicine, including psychology, sociology, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, health economics, and health services research. The common use of the construct suggests that there are varying underlying representations of the content and cause of disability (Johnston 1997). The term ‘disability’ has been used to refer to the WHO concepts of either impairment or handicap or a combination of disability and handicap. In some countries, the term disability may simply refer to the conditions that attract welfare support so that an assessment of 100 percent disability would mean that someone is entitled to the maximum benefit rather than being totally disabled.

2. Prevalence Of Disability

Estimates of the prevalence of disability vary according to the definition or types of disability as well as the threshold of severity that is chosen for inclusion in a study. In the UK, the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (OPCS) 1988 survey of disability found that 14 percent of adults living in private households have at least one disability ranging from slight to very severe (Martin et al. 1988). Disabling diseases vary in their effects on life expectancy and this also has implications for considering incidence and prevalence data. The most common disabilities in the 1988 survey were locomotion followed by hearing and personal care (for example, dressing or toileting). The most commonly cited causes of disability were musculoskeletal complaints (e.g., arthritis), ear complaints, eye complaints, diseases of the circulatory system, and nervous system complaints (e.g., stroke). Disabilities may arise from genetic disorders, from birth injuries, as a result of accidents, as well as due to disease. Martin et al. (1988) found the overall rate of disability rose with age, with almost 70 percent of disabled adults aged over 60. Of the most severely disabled adults, 64 percent were aged 70 or over. There were more disabled women then men. Even allowing for differing numbers of men and women in the population, the rate of disability among those aged 75 or over was still higher for women than for men, indicating that elderly women were more likely to be disabled than elderly men. Martin et al. (1988) found no evidence of ethnic differences in prevalence of disability.

3. How Disability Is Measured

A disability rating serves as a key indicator of care requirements, ability to remain independent in the community, and the nature and extent of participation in society. Disability is typically measured based on self-report or observers’ ratings of behavior, frequently the level of performance of basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL), such as eating, toileting, dressing, bathing, walking, doing housework, and shopping. However, the selection of items, the method of assessing performance, and the scaling of items to give an overall score, show immense diversity. Most measures involve self-report of either what one ‘can do’ or of what one has actually done. Some assessments require observing an activity to rate the ‘normality’ of performance. Others concentrate on whether the activity was achieved, rather than the manner of its accomplishment. Measures that elicit performance of movements assume that the disability is a constant, inherent aspect of the individual that can reliably be produced on demand. By contrast, measures of achievement of ADL use reports or performance under ordinary rather than assessment conditions. Recently, mobility limitations have been directly assessed using ambulatory monitoring techniques.

There have been considerable problems in identifying appropriate items and methods of scoring and scaling and variability in the rigor of measures used. Most measures use additive scaling, indicating a concept of equivalence of activities. In these measures, failure on feeding, self-care, or mobility would contribute in a similar manner to the overall score. Other measures use weighted additive scores, where failure on some items counts for more than failure on other items. For example, in the Sickness Impact Profile (Bergner et al. 1981), difficulties in walking a long distance count for less than difficulties in walking a short distance. In developing the OPCS scales, Martin et al. (1988) used a Thurstone scaling approach to create a set of scales for each area of disability, such as locomotion, dexterity, and personal care. For each scale, the value of each item was determined by judges’ ratings. The method of combining disabilities was also empirically derived to reflect the judgment of expert raters. It is heavily weighted by the individual’s most severe disabilities. This contrasts with averaging or additive measures which carry the implication that many mild disabilities, such as walking more slowly, being unable to walk half a mile, and being unable to climb stairs, may be equivalent to one severe disability; for example, being unable to walk at all. This diversity in the measurement of disability reflects the wide variation in views about the nature of disability.

4. Explanatory Models

The three main explanatory models of the nature of disability are the medical model, the social model, and the psychological model. The ICIDH model is a medical model since it conceptualizes disability within a predominantly pathological framework, explaining disability as a consequence of an underlying disease or disorder. However, a social model of disability conceptualizes disability in terms of limitations placed on the individual due to constraints in the social and physical environment and proposes that functional limitations are determined as much socially as biologically, for example, by the presence, attitudes, and actions of others (e.g., Oliver 1993). Psychological models conceptualize disability as a behavioral construct (e.g., Johnston 1996). These models suggest that disability is determined by psychological factors that influence behavior, for example, the individual’s beliefs, emotions, skills, and habits.

Medical, social, and psychological models are not necessarily in conflict. Although some level of disability experienced by an individual may be related to their degree of impairment, there is considerable evidence that much of the variance in disability experienced by an individual remains unexplained by underlying pathology or impairment (Johnston and Pollard 2001). For example, McFarlane and Brooks (1988) found that in people with rheumatoid arthritis, psychological factors predicted more variance in ADL three years later than impairment and disease severity measures. Cognitive and emotional manipulations have also influenced the level of disability experienced by individuals under conditions where impairment was not affected. Additionally, the major task of rehabilitation therapists is to enable patients to overcome disabilities, often without resolution of underlying impairments. Moreover, many social factors are likely to operate via psychological mechanisms to alter the relationship between the components of the ICIDH model; for example, an environment with barriers to mobility or an overprotective social environment may reduce the individual’s confidence with the result that their activities become even more limited. An explanatory model of disability which combines medical, psychological, and social factors would appear to be needed.

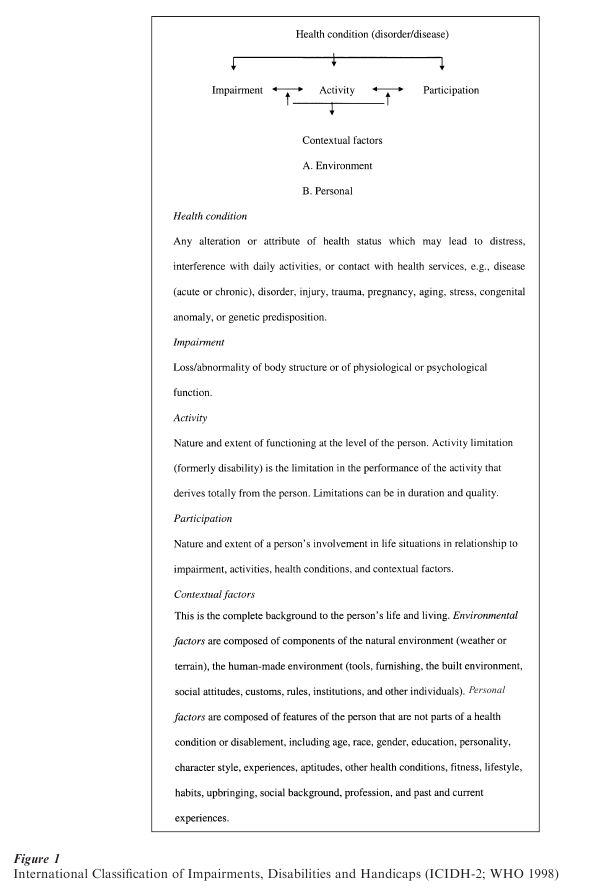

Indeed, the ICIDH model was recently modified to allow for the possibility that disability may be influenced by factors other than structure and function (WHO 1998). The revisions added complexity by proposing reverse causality, so that impairment may both result in, and result from, limitations in activity which may in turn determine, or be determined by, lack of social participation. It also introduced the possibility that contextual factors, both environmental and personal, can explain the level of disability experienced by an individual. In addition, the use of the terms ‘disability’ and ‘handicap’ were dropped in order to ‘avoid deprecation, stigmatization and undue connotations’ (WHO 1998, p. 19). Disability and handicap were redefined and renamed activity and participation. Activity is defined as the nature and extent of functioning at the level of the person and disability as the activity limitations of the individual person, whereas participation is defined in relation to the social context as the ‘nature and extent of a person’s involvement in life situations in relationship to impairment, activities, health conditions, and contextual factors.’ This amended model of the consequences of disease is depicted in Fig. 1.

While consistent with previous research which has shown a meager relationship between impairment and disability, and that changes in disability have occurred without concurrent changes in impairment, the ICIDH (WHO 1998) model is nevertheless vague about exactly which psychological and social factors contribute to explaining, and thereby predicting, disability.

5. What Predicts Disability?

Many studies, including investigations where the effects of impairment have been controlled statistically, and randomized controlled trials where impairment was equally distributed in the control and intervention groups, have shown disability to be predicted and influenced by emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and social factors.

5.1 Emotional Factors

How people feel may influence their level of disability. Patients’ emotional state is determined partly by their disposition and partly by situational factors such as the threats associated with their condition and treatment. Psychologists have often noted the association between disability and low mood or emotional disorder, and this is usually interpreted as emotional consequences of disability. However, most studies which examine the influence of emotional factors on disability are cross-sectional and observational in design, and it is therefore difficult to disentangle cause and effect. It seems likely that complex feedback loops occur. For example, while disability results in depression, depressed individuals are likely to be more disabled given comparable levels of impairment. Since emotional states are accompanied by physiological changes in the neuroendocrine, immune, and cardiovascular systems, it is also possible that negative emotions may influence disability by exacerbating impairments.

Nevertheless, there is evidence from longitudinal, prospective studies that emotional states, such as anxiety or depression, may influence the level of disability itself. For example, in a longitudinal study of middle-aged and older community residents, Meeks et al. (2000) found that depression predicted functional disability more strongly than disability predicted depression. In addition, changing emotions can have an immediate effect on disability levels. Fisher and Johnston (see Johnston 1997) used mood induction techniques to either increase or decrease anxiety (by asking about good or upsetting events) in two randomly allocated groups of patients with chronic pain. Patients’ disability was assessed by a lifting task before and after the experimental procedure, and results demonstrated that mood enhancement was associated with reduced levels of disability, while mood depression resulted in greater disability. It appears that emotional state can influence the level of disability independently of impairment.

5.2 Cognitive Factors: Attitudes And Beliefs

What people think or believe may influence their level of disability, particularly their beliefs about how much control they have over behaviors assessed as disability. Control cognitions are part of many theoretical frameworks constructed to predict and explain behavior. Two control cognitions, perceived personal control and self-efficacy, have been particularly associated with disability.

Perceived personal control or internal locus of control refers to the degree to which persons expect that an outcome is contingent upon their own behavior. It can be contrasted with beliefs in external control, i.e., the degree to which persons expect that the outcome is not under their control, but under the control of powerful others, or is unpredictable. The evidence suggests that patients with high perceived personal control beliefs have better outcomes. For example, patients suffering from a stroke or wrist fracture were found to have greater recovery of function if they had higher beliefs in personal control over their recovery, even allowing for initial levels of disability—a finding which has been replicated in a larger sample of stroke patients six months after discharge from hospital (see Johnston et al. 1999). Harkapaa et al. (1996) found that patients in a back pain program showed greater improvement in functional activity if they had weaker beliefs in control by powerful others. In an experimental study, Fisher and Johnston (1996) manipulated the control cognitions of chronic pain patients by asking them to recall occasions when they had achieved or failed to retain control. They found that increasing perceived control resulted in reduced disability, assessed by the observed performance on a lifting task before and after the manipulation, while decreasing perceived control resulted in increased disability. Given that these were immediate effects, it is clear that the results were not due to changes in impairment, suggesting that control cognitions may play a causal role in activity limitations.

Self-efficacy relates to individuals’ confidence in their ability to perform critical behaviors. Bandura (1997) proposes that there are four sources of information which are used as a basis for self-efficacy judgments: performance attainments, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and physiological state. It has been shown that successful performance leads to increased self-efficacy, whereas repeated failures result in lower self-efficacy. People with high self-efficacy beliefs are more likely to perform the behavior. Kaplan et al. (1984) examined exercise maintenance and found that changes in self-efficacy were associated with changes in walking activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Changes in self-efficacy have also been associated with changes in disability among participants in arthritis self-management courses (Lorig et al. 1989), in low back pain patients, in patients with fibromyalgia, and in coronary bypass patients.

5.3 Coping Behavior

What people do in order to cope with the stress imposed by their condition and the practical problems which arise from physical disability may affect their level of disability. For example, adherence to medication, diet, and rehabilitation regimens all may impact on disability. Coping refers to the procedures adopted to minimize stress and may or may not constitute effective management. Coping responses can be problem-focused or emotion-focused. Problem-focused coping includes attempts to modify or eliminate the sources of stress through one’s own behavior, i.e., solving the problem. Emotion-focused coping includes attempts to manage the emotional consequences of stressors and to maintain emotional equilibrium. A coping model that has frequently been applied in studies of patients with chronic disease is Leventhal’s Self-Regulation Model (see Brownlee et al. 2000). According to this model, the individual develops mental representations of their impairments which in turn determines what they do to cope. Dominant mental representations which determine coping behavior are: (a) identity of the condition: what they think it is; (b) timeline: the pattern over time (e.g., acute, chronic, or cyclical remitting); (c) cause: what caused their condition (e.g., if it was due to their own behavior or character); (d) control cure: if they perceive their condition can be controlled by their own or health professionals’ actions; and (e) consequences: what they believe they have experienced as a result of their condition and what they expect the outcome to be. These mental representations are proposed to influence coping with both the objective condition and the emotional reaction to the condition.

However, while some predictive studies have found coping associated with activity limitations (e.g., Evers et al. 1998), other studies have not. For example, Revenson and Felton (1989) found that coping did not predict change in disability in a six-month prospective study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Similarly, others have found that coping did not predict and therefore did not influence disability in people with chronic fatigue. It is possible that these findings are specific to these clinical conditions, where there is no clear action an individual can take to affect outcomes. Nevertheless, it is also possible that coping strategies are the result rather than the cause of disability.

5.4 Social Factors

Disability may be influenced by social factors such as stigmatizing reactions from others, overprotection by immediate family members, or carers’ social reinforcement of activity limitations. Evidence of social influences comes from comparisons of disability assessments by different health professionals. For example, nurses rated patients as more disabled than rehabilitation therapists over a 24-hour period (Johnston 1996). While differences in ratings are obviously not due to changes in impairment, they may be due to the different social demands on the patients in the two care contexts: nurses assist patients in achieving tasks, while rehabilitation therapists enable patients to perform the tasks themselves.

Disability may also be influenced by the level and type of formal or informal support available. While most informal support is provided by spouses—primarily for household assistance (Melzer et al. 1999), a social support network includes all members of the individual’s household, family and friends living nearby, as well as more distant contacts. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a small network soon after diagnosis predicted a greater decrease in mobility over the following year (Evers et al. 1998). The support can be practical, e.g., tangible help and assistance with information, or emotional, e.g., that makes the individual feel esteemed and valued. Both have been related to health outcomes and behavior. For example, Weinberger et al. (1986) found that biweekly telephone calls to people with osteoarthritis led to improved functional status six months later and attributed the gains to the effects of enhanced emotional social support.

6. Consequences Of Disability

Disability has a wide range of social and emotional consequences. For example, disability can impact on the person’s social functioning. Newsom and Schulz (1996) report that older people with impairments have fewer family and friendship contacts and less perceived belonging and perceived tangible aid. Johnston and Pollard (2001) found that disability predicted social participation (handicap) in stroke patients, with greater disability associated with lower social participation.

Disability also has consequences for emotional functioning (e.g., Meeks et al. 2000). Perhaps the most frequently used models in psychological studies of disability explore the impact of disability on emotional functioning. These models include: (a) mental health models where rates of disorder are assessed; (b) life-event models where the emotional response to the life event precipitating in the impairment disability is examined; and (c) stress models where the disability is seen as a stressor which elicits the strain evident as high levels of distress.

The nature of the underlying pathology, for example, whether a disease has static, fluctuating, or deteriorating patterns, is likely to temper the consequences of disability. Age at onset is also likely to be crucial, with earlier onset affecting education, family, housing, work, and leisure.

There is also evidence that disability has consequences for the people supporting the disabled person, impacting on their social and emotional functioning, as well as their health (see the review by Shulz and Quittner 1998). The effect of disability on caregivers may have further implications for the health outcomes of patients. For example, Elliott et al. (1999) found that the risk of disability and secondary complications increases for care recipients when carers have difficulty in adjusting to their new role demands.

The impact of disability is found to relate more closely to cognitive appraisals of functional limitations and coping resources than to objective indices of impairment and disability. For example, Schulz et al. (1994) proposed a model of the impact of impairment and disability, suggesting that negative affect is primarily due to the perceived loss of control rather then directly from impairment and disability.

7. Interventions

Interventions can be directed at reducing the disability or the impact of disability or both. Interventions directed at reducing the impact are similar to other cognitive behavioral programs that aim to reduce emotional and social consequences of life-events and difficulties: they concentrate on cognitive reframing and stress-management skills. Given the evidence that the individual’s perception of limitations, social support, and control appear to be predictors of emotional and quality-of-life outcomes, there is clearly potential to improve these outcomes without reducing impairment.

Interventions directed at reducing disability per se are more akin to other programs that aim to achieve behavioral change. These include stress management techniques or elements designed to enhance self-efficacy in order to increase motivation and to develop skills and habits required to achieve the performance of activities. Kaplan et al. (1984) showed improvements in disability for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease following cognitive and behavioral exercise programs. Lorig and colleagues have shown similar benefits from arthritis self-management programs designed to enhance self-efficacy (Lorig et al. 1989). Behavioral programs in which social attention is contingent on successful performance rather than on limitations have also been shown to decrease disability, especially in chronic pain patients.

Bibliography:

- Bandura A 1997 Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Freeman, New York

- Bergner M, Bobbitt R A, Pollard W A 1981 The sickness impact profile: Development and final revision of a health status measure. Medical Care 19: 787–805

- Brownlee S, Leventhal H, Leventhal E A 2000 Regulation, self-regulation, and construction of the self in the maintenance of physical health. In: Boekaerts M, Pintrich P R, Zeider M (eds.) Handbook of Self-Regulation. Academic Press, San Diego, CA

- Elliot T, Shewchuk R, Richards J S 1999 Caregiver social problem solving abilities and family member adjustment to recent-onset physical disability. Rehabilitation Psychology 44: 104–23

- Evers A W, Kraaimaat F W, Geenen R, Bijlsma J W 1998 Psychosocial predictors of functional change in recently diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy 36: 179–93

- Fisher K, Johnston M 1996 Experimental manipulation of perceived control and its effect on disability. Psychology and Health 11: 657–69

- Harkapaa K, Jarvikoski A, Estlander A 1996 Health optimism and control beliefs as predictors for treatment outcome of a multimodal back treatment program. Psychology and Health 12: 123–34

- Johnston M 1996 Models of disability. The Psychologist 9: 205–10

- Johnston M 1997 Representations of disability. In: Petrie K J, Weinman J A (eds.) Perceptions of Health and Illness. Harwood Academic Publishers, London

- Johnston M, Morrison V, MacWalter R S, Partridge C J 1999 Perceived control, coping and recovery from disability following stroke. Psychology and Health 14: 181–92

- Johnston M, Pollard B 2001 Problems with the sickness impact profile. Social Science and Medicine 52: 921–34

- Kaplan R M, Atkins C J, Reinsch S 1984 Specific efficacy expectations mediate exercise compliance in patients with COPD. Health Psychology 3: 223–42

- Lorig K, Chastain R, Ung E, Shoor S, Holman H R 1989 Development and evaluation of a scale to measure the perceived self-efficacy of people with arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 32(3): 7–44

- McFarlane A C, Brooks P M 1988 Determinants of disability in rheumatoid arthritis. British Journal of Rheumatology 27: 7–14

- Martin J, Meltzer H, Elliot D 1988 The Prevalence of Disability Among Adults. HMSO, London

- Meeks S, Murrell S, Mehl R C 2000 Longitudinal relationships between depressive symptoms and health in normal older and middle-aged adults. Psychology and Aging 15(1): 100–9

- Melzer D, McWilliams B, Brayne C, Johnson T, Bond J 1999 Profile of disability in elderly people: Estimates from a longitudinal population study. British Medical Journal 318: 1108–11

- Newsom J T, Schulz R 1996 Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychology and Aging 11(1): 34–44

- Oliver M 1993 Redefining disability: A challenge to research. In: Swain J, Finkelstein V, French S, Oliver M (eds.) Disabling Barriers—Enabling Environments. Sage, London

- Revenson T A, Felton B J 1989 Disability and coping as predictors of psychological adjustment to rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 57: 344–8

- Schulz R, Heckhausen J, O’Brien A T 1994 Control and the disablement process in the elderly. Journal of Social Beha iour and Personality 9(5): 139–52

- Schulz R, Quittner A L 1998 Caregiving for children and adults with chronic conditions: Introduction to the special issue. Health Psychology 17: 107–11

- Weinberger M, Hiner S L, Tierney W M 1986 Improving functional status in arthritis: The effect of social support. Social Science and Medicine 23(9): 899–904

- World Health Organization 1980 The International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps. World Health Organization, Geneva

- World Health Organization 1998 The International Classification of Impairments, Activities and Participation: A Manual of the Dimensions of Disablement and Health. www.who.int/msa/mnh/ems/icidh/introduction.htm