View sample Emotional Processing Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

It is now well established that systematic exposure to phobic stimuli markedly reduces associated fear and several theories about the psychological mechanisms underlying the efficacy of exposure therapy have been advanced (Craske 1999). Emotional processing theory (e.g., Foa and Kozak 1986) initially was advanced as one explanation of the effectiveness of exposure therapy in the treatment of anxiety disorders. This research paper traces the origin of the concept of emotional processing, describes emotional processing theory and how it accounts for the effectiveness of psychological therapies in treating anxiety disorders, and discusses recent developments in the concept of emotional processing.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. History Of The Emotional Processing Concept

The concept of emotional processing has it origin in Lang’s (1977) analyses of fear-relevant imagery in the context of behavior therapy and fear reduction. In studying the procedure of systematic desensitization, Lang et al. (1970) found three predictors of successful treatment: greater initial heart-rate reactivity during fear-relevant imagery, greater concordance between self-reported distress and heart rate elevation during fear-relevant imagery, and systematic decline in heart rate reactivity with repetition of the imagery. On the basis of these findings, Lang (1977, p. 863) suggested that ‘the psychophysiological structure of imagined scenes may be a key to the emotional processing which the therapy is designed to accomplish’. While Lang did not expand on the concept of emotional processing, in subsequent papers he further elaborated on the theory of emotional imagery in behavior therapy (e.g., Lang 1984).

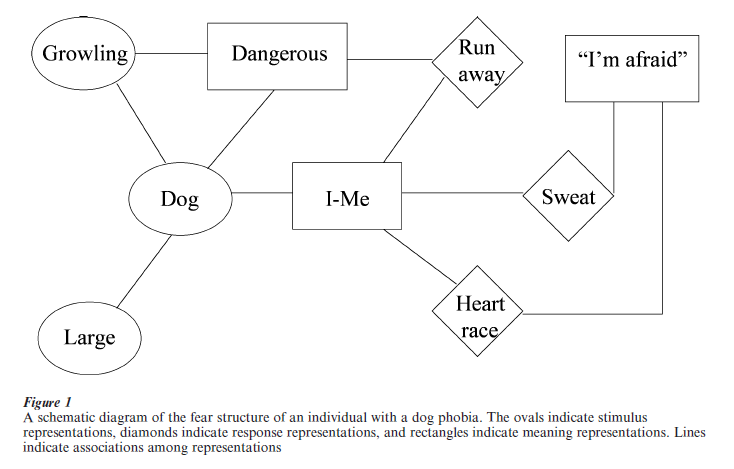

Lang’s (1977, 1984) theory holds that a fear image is a cognitive structure containing stimulus, response, and meaning information that serves as a program to avoid or escape from danger. For example (see Fig. 1), the fear structure of a dog phobic includes representations of dogs, representations of physiological and behavioral responses in the presence of dogs (e.g., rapid heart-rate, sweating, running away), and representations of meanings associated with dogs (e.g., ‘Dogs are dangerous’) and with responses to dogs (e.g., ‘Rapid heart rate and sweating mean that I am afraid’). The fear structure is activated by environ- mental input that matches some of the information stored in the structure. According to Lang (1977, p. 867), ‘the aim of therapy could be described as the reorganization of the image unit in a way that modifies the affective character of its response elements.’ He further proposed that for image modification to occur, the fear structure must be at least partially activated. Accordingly, it is this aspect of the theory that accounts for the relationship between physiological measures (e.g., elevated heart-rate reactivity) and good outcome in exposure therapy for fear. However, Lang did not specify how activation of the fear structure brings about alterations in the structure.

The concept of emotional processing was subsequently taken up by Rachman (1980, p. 51) who proposed a working definition of emotional processing as ‘a process whereby emotional disturbances are absorbed, and decline to the extent that other experiences and behaviors can proceed without disruption.’ Accordingly, successful processing would be evidenced by a person’s ability to confront a previously distressing event without evidencing signs of emotion- al distress. By contrast, several clinical phenomena such as persistent fears and obsessions, failures to benefit from treatment designed to reduce fears, and the return of fear after apparently ‘successful’ treatment would be evidence of failed or incomplete emotional processing.

Rachman (1980) noted that the majority of people are able successfully to process the upsetting events that occur in their lives and proposed a number of situational, personality, and contextual variables that are likely to produce difficulties in processing an emotionally disturbing event. For example, difficulties in emotional processing are likely to occur in generally anxious and introverted individuals who confront intense, dangerous, unpredictable, and uncontrollable events. Rachman further discussed factors that can facilitate emotional processing, such as prolonged exposures to fear relevant stimuli or images without distraction. Rachman’s analysis does not constitute a theory of emotional processing. Rather, it is an attempt to describe the sort of phenomena for which an adequate theory of emotional processing may provide an explanation. Indeed, as noted by Foa and Kozak (1986), Rachman’s approach to defining and analyzing emotional processing suffers from circular reasoning: the fear reduction that is attributed to successful emotional processing is the same evidence used to infer that successful emotional processing has occurred.

2. Emotional Processing Theory: Basic Concepts And Mechanisms Underlying Treatment

2.1 The Cognitive Structure of Fear

Building on Lang’s (1977, 1984) theory, Foa and Kozak (1986) conceptualized fear as a memory structure that serves as a blue print for escaping or avoiding danger that contains information about the feared stimuli, fear responses, and the meaning of these stimuli and responses. When a person is faced with a realistically threatening situation (e.g., a car accelerating at you) the fear structure supports adaptive behavior (e.g., swerving away). However, a fear structure becomes pathological when the associations among stimulus, response, and meaning representations do not accurately reflect reality in that harmless stimuli or responses are erroneously interpreted as being dangerous. Furthermore, characteristic differences between different anxiety disorders are thought to reflect the operation of specific pathological fear structures (cf. Foa and Jaycox 1999). For example, the fear structure of individuals with panic disorder with agoraphobia is characterized by fear of physical sensations associated with their panic symptoms (e.g., rapid breathing, heart palpitations) and interpretation of these sensations as meaning that they are having a heart attack or are going crazy. As a result of this misinterpretation, panic disordered individuals avoid locations they anticipate will give rise to panic attacks or similar bodily sensations, such as physical exertion.

By contrast, the fear structure of individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) involves associations among trauma-related harmful stimuli and similar but non-harmful stimuli, erroneous interpretation of safe stimuli as dangerous (e.g., ‘All men are rapists’), and erroneous interpretations of responses to mean self-incompetence (e.g., ‘My symptoms mean I can’t cope with this’). Accordingly, when encountering a trauma reminder, the PTSD sufferer experiences strong emotional reactions similar to those that occurred during the trauma. Support for these hypotheses comes from a study comparing traumatized individuals with and without PTSD to one another and to nontraumatized individuals using the Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI), a measure of negative cognitions about the self, negative cognitions about the world, and self blame. Individuals with PTSD showed higher scores on all three scales than did the other two groups who did not differ from one another (Foa et al. 1999).

2.2 Emotional Processing As Modification Of The Fear Structure

If fear behavior reflects the activation of an underlying cognitive fear structure, then changes in the fear structure will result in corresponding changes in behavior. Foa and Kozak (1986) proposed that psychological interventions known to reduce fear, such as exposure therapy, achieve their effects through modifying the fear structure. They further suggested that, ‘The hypothesized changes in the fear structure may be conceptualized as the mechanism for what Rachman (1980) has defined as emotional processing’ (Foa and Kozak 1986, p. 22).

2.3 Necessary Conditions For Emotional Processing

According to emotional processing theory (Foa and Kozak 1986), two conditions are necessary for therapeutic fear-reduction to occur. Similar to Lang (1977, 1984), Foa and Kozak suggested the fear structure must be activated in order for it to be available for modification. Activation occurs when a person is exposed to information that matches some of the information stored in the fear structure. But activation by itself is not sufficient. New information that is incompatible with the pathological aspects of the fear structure must also be available and incorporated into the existing structure for emotional processing to occur. Indeed, exposure to information that is consistent with the existing fear structure would be expected to strengthen existing associations. Although experiences may have the effect of either strengthening or weakening existing fear structures, the term emotional processing is reserved for modifications that result in fear-reduction.

2.4 Indicators Of Emotional Processing And Relation To Treatment Outcome

Fear and emotional processing are theoretical constructs that cannot be observed directly. Rather, they must be inferred through observable variables. Because emotional processing is being offered as an explanation of fear reduction, it is important that the indicators of emotional processing be different from the indicators of fear reduction. To avoid circularity, Foa and Kozak (1986) distinguished between measures of emotional processing during the course of exposure therapy and treatment outcome. Specifically, they proposed that emotional processing can be inferred from: (a) self-reports (e.g., ‘I’m afraid’) and physiological reactivity (e.g., elevated heart rate) that are indicative of fear activation; (b) gradual decreases of these measures during continued exposure to fear relevant information; and (c) diminished initial fear reactions across successive exposures. In contrast to these indicators, Foa and Kozak viewed treatment outcome as a much broader notion that encompasses variables not specifically targeted in treatment, such as the quality of a person’s job performance, personal relationships, and their degree of life satisfaction.

Several studies are consistent with the hypothesized relationship between indicators of emotional processing and treatment outcome. For example, individuals with PTSD experience distressing intrusive thoughts about their traumatic experience; carefully avoid people, places, and activities that remind them of the traumatic event; and experience disruptions in memory, concentration, and sleep. An effective treatment for PTSD is imaginal exposure to memories of the traumatic experience (Shalev et al. 1996). It has been found that individuals who exhibited fear activation during imaginal reliving, followed by decline across sessions achieved better outcome (e.g., fewer intrusive thoughts, less avoidance, and improvements in memory, concentration, and sleep) than individuals who did not exhibit fear activation or who exhibited fear activation with minimal habituation across sessions (cf. Foa 1997). The validity of these predictors of outcome has been demonstrated in other anxiety disorders as well, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder and specific phobias (Foa and Kozak 1986).

2.5 Sources Of Corrective Information

It is easy to see how exposure therapy, in which fearful individuals are helped to confront feared images or situations, results in activation of a fear structure. But what kind of information does exposure therapy provide to correct erroneous associations among the stimulus, response, and meaning representations in the fear structure?

One important source of corrective information is habituation, by which repeated exposure to a stimulus that reliably elicits a specific response results in a decline in that response. Foa and Kozak (1986) proposed that habituation of physiological responses within an exposure therapy session, one of the indicators of emotional processing, constitutes an important source of information for modifying aspects of the fear structure. For example, habituation generates new response information about the absence of physiological responding in the presence of the phobic stimulus that is incompatible with prior response information. Physiological habituation also counters erroneous meaning representations underlying the cognition that fear will persist until escape occurs. Repeated and prolonged exposure may also provide corrective information as to the realistic likelihood of feared consequences. For example, the fear structure of an individual with obsessive compulsive disorder may include meaning representations with unrealistically high estimations of the probability of contracting a severe illness from touching doorknobs. As a result, doorknobs are carefully avoided thereby preventing the person from learning that touching doorknobs does not pose a serious health risk. Treatment through exposure (e.g., touching dirty doorknobs) and response prevention (e.g., refraining from washing) provides the corrective information that the probability of becoming sick after touching a doorknob is actually extremely low.

3. Recent Advances In Emotional Processing Theory

3.1 Mechanisms Underlying Natural Recovery From Trauma

Studies investigating patterns of reactions to a trauma over time indicate that individuals differ in their ability to successfully process the traumatic event and thus recover naturally with the passage of time. While most trauma victims process the trauma successfully, a substantial minority fails to do so and consequently develops chronic PTSD (Foa 1997). Why do some traumatized individuals recover and others go on to develop chronic disturbances? Foa (1997) suggested that three common mechanisms underlie both natural recovery from trauma and reduction of PTSD severity via treatment. The first mechanism is emotional engagement with the trauma memory, which in the context of exposure therapy has been termed fear activation. In relation to natural recovery, emotional engagement refers to fear activation that occurs upon encountering a trauma reminder in the natural environment. Just as fear activation has been found positively associated with treatment outcome, the absence of emotional engagement has been found to be associated with poor natural recovery following a traumatic event. For example, individuals who dissociate during or shortly after experiencing a traumatic event experience greater PTSD symptom severity later on, compared to those who do not dissociate. The dissociation phenomenon connotes the absence of emotional engagement with the trauma memory and hence, according to emotional processing theory, will retard emotional processing. A delay in the peak reaction to a traumatic event may also be conceptualized as the absence of emotional engagement and thus is expected to hinder emotional processing and subsequent recovery. Consistent with this hypothesis, individuals whose peak symptom severity occurred within two weeks of the traumatic event were less symptomatic 14 weeks later than were individuals whose symptoms peaked between 2–6 weeks after the event. A second mechanism hypothesized to underlie both natural recovery and improvement with treatment is the degree of organization or articulation of the trauma narratives (Foa 1997). In support of this hypothesis, a higher degree of narrative articulation shortly after the trauma predicted greater recovery (lower PTSD symptom severity) three months later. In the same vein, exposure therapy for PTSD was associated with increased organization and decreased disorganization of the trauma narrative over the course of treatment, and those changes were correlated with symptom improvement.

The third hypothesized mechanism for recovery is a change in core cognitions about the world and the self. As discussed earlier, two basic dysfunctional cognitions are thought to underlie PTSD: the world is completely dangerous and the self is totally incompetent. It follows that recovery would be associated with less negative cognitions (Foa and Jaycox 1999). Indeed, in a longitudinal study of crime victims, individuals who retained their PTSD diagnosis three months after their assault exhibited more negative cognitions compared to those who no longer had PTSD. Similarly, cognitions about the world and self were less negative after treatment for PTSD than they had been before treatment (see Foa 1997, for discussion of the preceding two studies).

The ways in which exposure therapy is thought to promote fear activation and modification of erroneous cognitions have been explicated earlier. But how does emotional processing theory account for natural recovery? It is proposed that natural emotional processing and the consequent recovery occurs via repeated activation of the trauma memory in daily life through engagement with trauma-related thoughts and feelings, sharing them with others, and confronting trauma-reminder stimuli. In the absence of repeated traumatization or ‘emotional breakdown,’ these natural exposures contain information that disconfirms the common post-trauma cognition that the world is a dangerous place. For example, a rape victim may repeatedly encounter men that are physically similar to the perpetrator, thus activating the trauma memory structure. As these encounters do not lead to additional assaults, the natural initial postrape inclination to view the world as entirely dangerous is not confirmed and thus gradually subsides. In addition, repeated thinking or talking about the traumatic event promotes habitation of negative emotions and the generation of an organized trauma narrative. By contrast, individuals who avoid engaging with the traumatic memories by either suppressing related thoughts and feelings or avoiding trauma-related situations, do not have the opportunity to form an organized narrative or disconfirm the initial posttrauma negative cognitions and thus develop chronic disturbances. Indeed, mothers who lost their babies to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and were able to share their loss with a supportive social network resolved their grief more satisfactory 18 months after the trauma than did mothers who were not able to share their grief with supportive others (Lepore et al. 1996).

3.2 Emotional Numbing And Emotional Processing In PTSD

In an apparent paradox, individuals with PTSD frequently report experiencing intense negative emotions when reminded about the traumatic (re-experiencing) while also having difficulty experiencing and expressing emotions in situations that call for an emotional response (emotional numbing). To explain this paradox, Litz et al. (2000) hypothesized that the strong emotional reactions cued by trauma reminders among individuals with PTSD temporarily depletes their emotional resources, thereby reducing emotional responsiveness to subsequent events. Consistent with this hypothesis, veterans with PTSD who were first shown a video tape of combat images and then asked to rate a series slides depicting emotionally positive images (e.g., a baby) were emotionally more reactive to the combat video, but less reactive to the positive slides than veterans without PTSD. In contrast, no differences between groups emerged when the veterans viewed neutral images (e.g., furniture) before rating the positive slides. Thus, veterans with PTSD displayed emotional numbing for the positive slides, but only after first experiencing negative emotional arousal.

The research by Foa and co-workers (see Foa 1997) on the consequences of emotional nonengagement and by Litz et al. (2000) on the relationship between arousal and emotional numbing suggests two ways in which extreme emotional reactivity following a traumatic event may interfere with emotional processing and recovery. According to Foa acute emotional reactivity can lead to extensive avoidance, thereby preventing exposure to corrective information. Litz and co-workers proposed that chronic emotional reactivity can lead to emotional numbing, thereby reducing emotional engagement with the trauma memory.

3.3 The Effects Of Corrective Experiences: Alteration Of Existing Cognitive Structures Or Development Of New Cognitive Structures?

Foa and Kozak (1986) defined emotional processing as a change in the pathological elements of an existing fear structure following exposure to corrective information. A plausible alternative is that exposure to corrective information results in the formation of a new memory structure that coexists with the old fear memory rather than replacing it (Bouton 1988). Accordingly, a person’s behavior in a given situation will be determined by which of the two structures is activated. From Foa and Kozak’s perspective, the return of fear following successful treatment represents a further change in the fear structure. Bouton’s theory would view relapse as a reduction in the accessibility of the new nonfearful memory. Support for Bouton’s hypothesis comes from research conducted by Craske and co-workers (cf. Craske 1999), demonstrating that certain procedural variations in treatment by exposure therapy produced less between session fear reduction, but prevented the long-term return of fear at follow-up.

3.4 Worry And Depressive Rumination

Emotional processing concepts have been utilized in the analysis of worry (Borkovec and Lyonfields 1993) and depressive rumination (Teasdale 1999). Although somewhat different analyses have been offered for these two phenomena, both Borkovec and Teasdale suggested that cognitive processing in one channel or at one level of meaning (linguistic conceptual or propositional) may interfere with processing in another channel or level of meaning (imagery or implicational). Specifically, on the basis of studies showing that verbal articulation of fearful material results in less physiological arousal than imagining the same material (e.g., Vrana et al. 1986), Borkovec and coworkers have proposed that worry serves to inhibit emotional imagery. The short-term consequence of worry is to minimize emotional distress by limiting activation of the fear structure. However, the long-term consequence of avoiding full activation of the fear structure, as discussed above in the context of emotional numbing and emotional nonengagement, is to inhibit emotional processing and thereby maintain the worry.

Although the concept of emotional processing has generally been limited to the field of anxiety, Teasdale and co-workers (cf. Teasdale 1999) have proposed an emotional processing model of depression. The model distinguishes between two different, but interacting levels of cognitive meaning, and proposes three different configurations of the interactions between these levels of meaning, also referred to as the ‘three modes of mind.’ One level of meaning is propositional, corresponding to the kind of information that can be conveyed in a single sentence. The other, implicational, represents higher order meaning derived from recurring patterns or themes. In the case of depression, the implicational meaning of experiences such as failing a class or the break-up of an important relationship may be a failure in all aspects of one’s life. Importantly, the model posits that emotions are directly generated by the implicational level, while the propositional level of meaning only effects emotional states indirectly through the continual cycling of information between the two levels of meaning. Depressive rumination involves the cycling of depresogenic information between these two levels of meaning, thereby generating and maintaining dysphoria.

Teasdale (1999) further suggested that each meaning level can operate in one of two modes. In the direct mode, processing occurs in real time, whereas in the buffered mode information is allowed to accumulate before it is processed further. Although both levels of meaning can be operating in direct mode at the same time, only one level can be buffered at a given time. This yields three possible configurations, each one having different consequences for the person’s emotional experience. When neither level of meaning is buffered, ‘mindless emoting’ occurs, in which people identify themselves with their emotional reactions and engage in little self-reflection. When the propositional level of meaning is buffered, individuals are said to be in the ‘conceptualization doing’ configuration in which they think about themselves and their emotions as objects and develop goal-oriented strategies to cope with their problems and emotions. For example, depressive rumination frequently involves the person thinking about the nature, causes, and consequences of their depression. The third configuration, called ‘mindful experiencing being,’ occurs when the implicational level is buffered and is characterized by ‘integrated cognitive-affective inner exploration, use of present feelings and ‘‘felt senses’’ as a guide to problem solution and resolution, and a non-evaluative awareness of present subjective-self-experience’ (p. S77).

Within this model of depression, Teasdale (1999) has defined effective emotional processing as ‘processing that leads to modification of the affect-related schematic models [i.e. implicational level of meaning] that support processing configurations maintaining dysfunctional emotion’ (p. S65). He further hypothesizes that emotional processing will occur only when the implicational system is buffered, thereby allowing the integration of new and old information. Accordingly, two general strategies can be used to promote changes in implicational meaning. One strategy is to help depressed individuals create and encode in memory new implicational meanings, and many current cognitive therapy techniques (e.g., cognitive restructuring) help in doing so, although such techniques may run the risk of maintaining the conceptualizing doing configuration. A second strategy, unique to Teasdale’s theorizing, is to help people learn to shift from either of the two modes of mind that do not promote emotional processing (mindless emoting and conceptulizing doing) to the one that does (mindful experiencing being). This involves exercises in mindfulness, similar to some forms of meditation, in which individuals learn to become aware of, and acknowledge depresogenic thoughts without exclusively focusing on them. Teasdale found that a treatment program combining traditional cognitive therapy interventions with mindfulness exercises was more effective in preventing relapses among individuals with recurrent major depression than was cognitive therapy alone.

4. Concluding Comments

Emotional processing theory was advanced by Foa and Kozak (1986) primarily to account for the effectiveness of exposure therapy in the reduction of anxiety. However, consideration of its historical antecedents (Lang 1977, Rachman 1980) indicates the concept of emotional processing originally was conceived more broadly. Rachman (1980) in particular proposed that the concept should encompass a range of phenomena that includes, but is not limited to, anxiety and the efficacy of exposure therapy. In keeping with this, recent advances in such topic areas as natural recovery following trauma (Foa 1997), PTSD symptom structure (Litz et al. 2000), worry (Borkovec 1993) and relapse following recovery from depression (Teasdale 1999) have extended the domain of emotional processing theory and demonstrate its continued heuristic value.

At the same time, questions remain for future research as to the nature and limits of emotional processing, two of which are briefly noted. First, does exposure to corrective information alter existing cognitive structures, as proposed by Foa and Kozak (1986), or does it result in the acquisition of a new memory (Bouton 1988, Craske 1999)? Resolution of this issue has implications for understanding the process of relapse and development of relapse-prevention strategies. Second, to what extent do procedures that promote emotional processing of fear and anxiety promote the emotional processing of other problematic emotional reactions, such as sadness depression, anger, or guilt? In exposure therapy, an important source of corrective information is habituation. However, it may be that these other emotions do not habituate (Pitman et al. 1991) and that alternative procedures may be needed to promote their emotional processing, such as traditional cognitive restructuring techniques and mindfulness strategies (Teasdale 1999). Thus, resolution of this issue has implications for the design of interventions for other problematic (nonfear) emotional reactions.

Bibliography:

- Borkovec T D, Lyonfields J D 1993 Worry: Thought suppression of emotional processing. In: Krohne H W (ed.) Attention and A voidance. Hogrefe & Huber, Seattle, WA, pp. 101–18

- Bouton M E 1988 Context and ambiguity in extinction of emotional learning: Implications for exposure therapy. Beha vour and Research Therapy 26: 13–149

- Craske M G 1999 Anxiety Disorders: Psychological Approaches to Theory and Treatment. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

- Foa E B 1997 Psychological processes related to recovery from a trauma and an effective treatment for PTSD. In: Yehuda R, McFarlane A (eds.) Psychobiology of PTSD Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, New York, pp. 410–24

- Foa E B, Ehlers A, Clark D M, Tolin D F, Orsillo S M 1999 The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment 11: 303–14

- Foa E B, Jaycox L H 1999 Cognitive-behavioral theory and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Speigel D (ed.) Efficacy and Cost-effectiveness of Psychotherapy. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, pp. 23–61

- Foa E B, Kozak M J 1986 Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin 99: 20–35

- Lang P J 1977 Imagery in therapy: An information processing analysis of fear. Behavior Therapy 8: 862–86

- Lang P J 1984 Cognition in emotion: Concept and action. In: Izard C, Kagan J, Zajonc R (eds.) Emotion, Cognition and Behavior. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 193– 206

- Lang P J, Melamed B G, Hart J 1970 A psychophysiological analysis of fear modification using an automated desensitization procedure. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 76: 220–34

- Lepore S J, Silver R C, Wortman C B, Wayment H A 1996 Social constraints, intrusive thoughts, and depressive symptoms among bereaved mothers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 271–82

- Litz B T, Orsillo S M, Kaloupek D, Weathers F 2000 Emotional processing in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Ab-normal Psychology 109: 26–39

- Pitman R K, Altman B, Greenwald E, Longpre R E, Macklin M L, Poire R E, Steketee G S 1991 Psychiatric complications during flooding therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 52: 17–20

- Rachman S 1980 Emotional processing. Behaviour and Research Therapy 18: 51–60

- Shalev A, Bonne O, Eth S 1996 Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A review. Psychosomatic Medicine 58: 165–82

- Teasdale J D 1999 Emotional processing, three modes of mind and the prevention of relapse in depression. Behaviour and Research Therapy 37: S53–S77

- Vrana S R, Cuthbert B N, Lang P J 1986 Fear imagery and text processing. Psychophysiology 23: 247–53