Sample Negotiation Analysis Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Introduction

The term ‘negotiation analysis’ encompasses an emergent body of work that seeks to generate prescriptive theory and advice for parties wishing to negotiate in a ‘rational’ manner, without necessarily assuming that the other side(s) is a strategically sophisticated, rational actor.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

To what bodies of theory and empirical work might one turn for advice in a negotiation over selling a car or forging a global warming treaty? Decades of psychological studies of people negotiating offer many powerful insights but generally lack a prescriptive theory of action. Instead, this behavioral approach has largely sought accurate descriptions and analytic explanations of how negotiators do act. What they should do often remains an implicit or ad hoc implication of this careful work.

Decision analysis, the practically oriented cousin of decision theory, would seem a logical candidate to fill this prescriptive void. It suggests a systematic decomposition of the problem: structuring and sequencing the parties’ choices and chance events, then separating and subjectively assessing probabilities, values, risk, and time preferences. A von Neumann– Morgenstern expected utility criterion aggregates these elements in ranking possible actions to determine the optimal choice. This approach is well-suited to decisions ‘against nature,’ in which the uncertainties—such as the probability that a hurricane will strike Miami in August—are not affected by the choices of other involved parties anticipating one’s actions.

Yet when decision-making is interactive—as is true in negotiation, where each party’s anticipated choices affects the other’s and vice versa—assessment of what the other side will do qualitatively differs from assessment of ‘natural’ uncertainties. Of course, the theory of games was developed to provide a logically consistent framework for analyzing such interdependent decision-making. Full descriptions of the courses of action open to each involved party are encapsulated into ‘strategies.’ Rigorous analysis of the interaction of strategies leads to a search for ‘equilibria,’ or plans of action such that each party, given the choices of the other parties, has no incentive to change its plans. A great deal of analysis by game theorists seeks conditions for unique equilibria among such strategies (von Neumann and Morgenstern 1944, Luce and Raiffa 1957, Aumann 1989).

Game theory has been especially useful for understanding repeated negotiations in well-structured financial situations. It has offered useful guidance for the design of auction and bidding mechanisms, has uncovered powerful competitive dynamics, has usefully analyzed many ‘fairness’ principles, and now flourishes both on its own and in applications such as microeconomic theory. Despite signal successes, the dominant game-theoretic quest to predict equilibrium outcomes resulting from the strategic interactions of fully rational players often lacks prescriptive power in negotiations.

Three major aspects of mainstream game theory, discussed at length in Sebenius (1992), contribute to this ‘prescriptive gap.’ First, on standard assumptions, there are often numerous plausible equilibrium concepts, each with many associated equilibria—and no a priori compelling way to choose among them. Second, even where one party wishes to act rationally, the other side may not behave as a strategically sophisticated, expected utility-maximizer—thus rendering conventional equilibrium analyses less applicable. A large and growing body of evidence—especially in ‘behavioral game theory’ and experimental economics—suggests that people systematically and significantly violate the canons of rationality. Third, the elements, structures, and ‘rules’ of many negotiating situations are not completely known to all the players, and even the character of what is known by one player may not be known by another. The frequent lack of such ‘common knowledge’ limits—from a prescriptive standpoint—much equilibrium-oriented game analysis, though recent work has begun to relax the widespread understanding that common knowledge of the situation was essential to game models (Aumann and Brandenburger 1995). Even where it is possible to bend such a situation into the form of a well-posed game, and gain insights from it, the result may lose prescriptive relevance.

2. The Negotiation Analytic Response

If descriptive psychological approaches to negotiation lack a prescriptive framework, if decision analysis is not directly suited to interactive problems, and if traditional game theory presupposes too much rationality and common knowledge, then ‘negotiation analysis’ represents a response that yokes the prescriptive and descriptive research traditions. Using Howard Raiffa’s (1982) terms, unlike the ‘symmetrically prescriptive’ approach of game theory, wherein fully rational players are analyzed in terms of what each should optimally do given the other’s optimal choices, the ‘asymmetrically prescriptive descriptive’ approach typically seeks to generate prescriptive advice to one party conditional on a (probabilistic) description of how others will behave. This need not mean tactical naivete; as appropriate, the assessments can incorporate none, a few, or many rounds of ‘interactive reasoning.’

Works that embody the spirit of this work can be found as early as the late 1950s. While Luce and Raiffa’s Games and Decisions (1957) was primarily a brilliant synthesis and exposition of game theory’s development since von Neumann and Morgenstern’s (1944) classic work, Luce and Raiffa began to raise serious questions about the limits of this approach in analyzing actual interactive situations. Perhaps the first work that could be said to be in the spirit of ‘negotiation analysis’ was The Strategy of Conflict by Thomas Schelling (1960). Its point of departure was game-theoretic but it proceeded with less formal argument and the analysis had far broader direct scope. Though nominally in the behavioral realm, Walton and Mckersie’s Behavioral Theory of Labor Negotiation (1965) drew on Schelling’s work as well as rudimentary decision and game theories.

The first overall synthesis of this emerging field appeared with Raiffa’s (1982) The Art and Science of Negotiation, elaborated in Raiffa (1997). Building on Sebenius (1984), this approach was systematized into an overall method in Lax and Sebenius’ The Manager as Negotiator (1986). Negotiation Analysis (1991), edited by Peyton Young, furthered this evolving tradition, which was characterized and reviewed in Sebenius (1992). Further contributions in the same rationalist vein were included Zeckhauser et al. (1996), Arrow et al. (1995), and, adding insights from organizational and information economics, in Mnookin et al. (2000).

Meanwhile, another group of researchers was coming to a negotiation analytic view from a behavioral point of departure. With roots in the cognitive work of behavioral decision theorists, e.g., Bell et al. (1988), behavioral scholars began in the early 1990s to explicitly link their work to that of Raiffa and his colleagues. In particular, Neale and Bazerman’s Cognition and Rationality in Negotiation (1991), Bazerman and Neale (1992), and Thompson (2001) pulled together and developed a great deal of psychological work on negotiation in an asymmetrically prescriptive descriptive framework. These efforts began systematically to build up more structure on what had been, in the works of Raiffa et al. a largely ad hoc descriptive side of the ledger.

3. Elements Of A Negotiation Analytic Approach

Full negotiation analytic accounts (e.g., Sebenius 1992, 2000) generally consider the following basic elements: the actual and potential parties; their perceived interests; alternatives to negotiated agreement; the linked processes of ‘creating’ and ‘claiming’ value; and the potential to ‘change the game’ itself.

3.1 Parties

In the simplest negotiation, two principals negotiate with each other. Yet potentially complicating parties such as lawyers, bankers, and other agents may be present as may multiple internal factions with very different interests. The crucial first step for an effective negotiation analysis is to map the full set of potentially relevant parties in the context of the decision processes.

3.2 Interests

The next step is to probe deeply for each relevant party or faction’s underlying interests and to assess their tradeoffs carefully. When individuals or groups with different concerns constitute a negotiating ‘side,’ it is no longer in general possible to specify overall tradeoffs; however, carefully tracing which set of interests is ascendant according to the internal bargaining process of given factions may continue to provide insights. Raiffa (1982) offers an extended discussion of assessing tradeoffs in negotiation, building on extensive work by Keeney and Raiffa (1976, Sebenius 1992). This assessment is radically subjective in the sense that less tangible concerns for self-image, fairness, process, precedents, or relationships can have the same analytic standing as the ‘harder’ or ‘objective’ interests such as cost, time, and quality that are common to traditional economic approaches.

It is often useful to distinguish the full set of the parties’ underlying interests from the issues under negotiation, on which positions or stands are taken. The connections among positions on issues and interests are rarely simple. Sometimes a focus on deeper interests can unblock a stubborn impasse over incompatible positions that relate only partially to the parties’ real concerns; in other cases, emphasizing interests will only generate hopeless conflict when mutually beneficial agreement on certain overt positions could be reached.

3.3 Alternatives To Negotiated Agreement

People negotiate in order to satisfy the totality of their interests better through some jointly decided action than they could otherwise. Thus, for each side, the basic test of a proposed joint agreement is whether it offers higher subjective worth than that side’s best course of action absent agreement. In examining a negotiation, one should analyze each party’s perceptions of its own—and the others’—valuations of their alternatives to negotiated agreement.

Alternatives to agreement may be certain, with a single attribute: an ironclad competing price quote for an identical new car. They may be contingent and multi-attributed: going to court rather than accepting a negotiated settlement can involve uncertainties, trial anxieties, costs, time, and precedents that contrast with the certain, solely monetary nature of a pretrial accord. No-agreement alternatives may also involve potentially competing coalitions, threats, and counterthreats or the necessity to keep negotiating indefinitely. Various analytic tools from decision analysis to optimal search theory may aid in assessment of such alternatives (see Sebenius 1992 for references).

While this evaluation provides a strict lower bound for the minimum worth (the ‘reservation price’) required of any acceptable settlement, alternatives to agreement also play tactical roles. The more favorably negotiators portray their best alternative course of action and willingness to ‘walk away,’ the smaller is the ostensible need for the negotiation and the higher the standard of value that any proposed accord must reach. Moves ‘away from the table’ that shape the parties’ alternatives to agreement can strongly affect negotiated outcomes. Searching for a better price or another supplier, cultivating a friendly merger partner in response to a raider, or preparing an invasion should talks fail, may influence negotiations more than sophisticated tactics employed ‘at the table’ such as clever opening offers or patterns of concession.

3.4 Representing The Structure

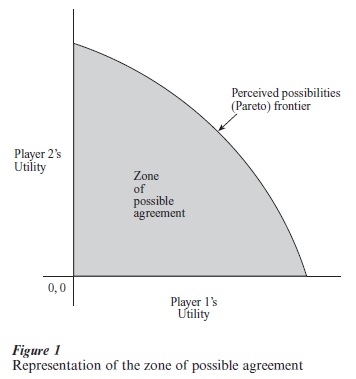

Imagine that two negotiators have thought hard about their underlying interests in different possible settlements of the apparent issues. Further, suppose that they have a relatively clear, if possibly changing, assessment of their tradeoffs and have compared them to the value of their best no-agreement alternatives. Each has a sense of any ‘rules of engagement’ that structure their interaction. From the viewpoint of each party, a set of possible agreements has been envisioned. Assume that an analyst were privy to the results of these evaluations by each side, along with the (likely asymmetric) distribution of information about interests, beliefs, no-agreement options, and possible actions; these evaluations need not be common knowledge of the parties. The situation might be familiarly represented as in Fig. 1.

The origin represents the value of failing to reach agreement: each side’s best alternative to agreement implies the location of this point. The ‘Pareto frontier’ in the northeast part of the graph represents the evaluations of the set of those possible agreements on the issues that could not be improved on from the standpoint of either party without harming the other. In general, neither side knows the location of the frontier, only theoretically that it is there. The entire shaded region—bounded by the two axes and the frontier—is the ‘zone of possible agreement.’ In general, each party has its own perceptions of it. (In a purely distributive bargain, with no room for joint gains beyond the fact of agreement, the shaded region would collapse to a diagonal frontier.) Since this representation is quite general, it can in principle encompass the whole range of possible interests, alternatives, and agreements.

3.5 From Structure to Outcome: Favorable Changes in the Perceived Zone of Possible Agreement

This is the point at which game-theoretic and negotiation-analytic approaches tend to diverge. A game theorist would typically tighten the above specification of the situation, presume common knowledge of the situation and strategic rationality of the parties, and, by invoking a rigorous concept of equilibrium, investigate the predicted outcome(s) of the interaction. Indeed, as Rubenstein’s insightful commentary noted, ‘for forty years, game theory has searched for the grand solution’ that would achieve a

prediction regarding the outcome of interaction among human beings using only data on the order of events, combined with a description of the players’ preferences over the feasible outcomes of the situation. (1991, p. 923)

Even with as powerful and ubiquitous a concept as that of the Nash equilibrium in non-cooperative games, however, it is often impossible, even with the imposition of increasingly stringent requirements or refinements to limit a game’s equilibrium outcomes to a unique or even small number of points. Often there is an infinitude of such outcomes. As Tirole noted when explaining why ‘we are now endowed with nearly a dozen refinements of perfect Bayesian equilibrium,’ the

leeway in specifying off-the-equilibrium-path beliefs usually creates some leeway in the choices of equilibrium actions; by ruling out some potential equilibrium actions, one transforms other actions into equilibrium actions. (1988, p. 446)

Frequently this implies an infinite number of perfect Bayesian equilibria.

Despite insights into how rational players might select from among multiple Nash equilibria (Harsanyi and Selten 1988), the rationale for a particular choice may ultimately seem arbitrary. As Kadane and Larkey remark,

we do not understand the search for solution concepts that do not depend on the beliefs of each player about the others’ likely actions, and yet are so compelling that they become the obvious standard of play for all those who encounter them. (1982, pp. 115–6)

This seems especially apt in light of their observation that ‘solution concepts are a basis for particular prior distributions’ and hence

the difficulty in non-zero sum, N-person game theory of finding an adequate solution concept: no single prior distribution is likely to be adequate to all players and all situations in such games. (1982, pp. 115–6)

Since each party should accept any settlement in the zone of possible agreement rather than no agreement, Schelling (1960) made the potent observation that the outcome of such a situation could only be unraveled by a ‘logic of indeterminate situations.’ Without an explicit model or formal theory (equilibrium-based or other) adequate to map structure and tactics onto bargaining outcomes with confidence, how can an individual negotiator or interested third party decide what to do? In the (often implicit) view of many negotiation analysts, the negotiator’s subjective distribution of beliefs about the negotiated outcome conditional on using the proposed tactics must be compared with his subjective distribution of beliefs about the outcome conditional on not using them. The tactic is attractive if the former distribution gives him higher expected utility than the latter.

Such ‘improvement’ has a subjective basis analogous to the Rothschild and Stiglitz (1970) characterization of a subjectively perceived ‘increase’ in risk. Specifying these distributions may require an internalized and subjective model of the bargaining process, since no such general model exists; where there is a well-developed and applicable game-theoretic model, of course, it should be used. Of course, the ‘better’ the empirical and theoretical basis for the assessment, the ‘better’ the subjective distributions of outcomes.

Much negotiation analytic work consists in improving the basis for assessing such outcome distributions. To do this, analysts pay attention to the special structure and dynamics that derive from the joint decision-making among parties, some of whom may be ‘boundedly’ rational.

3.6 Improving The Basis For Assessing Outcome Distributions I: Fundamental Processes Of Negotiation

At bottom, negotiation processes involve both (a) actions to enhance what is jointly possible through agreement (‘creating value’), and (b) actions to allocate the value of agreement (‘claiming value’).

(a) Creating Value. In most negotiations, the potential value of joint action is not fully obvious at the outset. ‘Creating value’—that is, reaching mutually beneficial agreements, improving them jointly, and preventing conflict escalation—requires an approach often associated with ‘win-win,’ ‘integrative,’ or ‘variable sum’ encounters: to share information; communicate clearly; be creative; and productively channel hostilities. Yet regardless of whether one adopts a cooperative style or not, it is useful to have an analytic guide as to the underlying substantive bases for joint gains and how to realize them by effective dealcrafting.

First, apart from pure shared interests, negotiators may simply want the same settlement on some issues. Second, where economies of scale, collective goods, alliances, or requirements for a minimum number of parties exist, agreement among similar bargainers can create value. Third—and most interestingly—though many people instinctively seek ‘common ground’ and believe that ‘differences divide us,’ it is often precisely the differences among negotiators that constitute the raw material for creating value. Each class of difference has a characteristic type of agreement that makes possible its conversion into mutual benefit. For example, differences in relative valuation suggest joint gain from trades or from ‘unbundling’ differently valued attributes. Differences in tax status, liquidity, or market access suggest arbitrage. Complementary technical capacities can be profitably combined. Probability and risk aversion differences suggest contingent agreements or bets. Differences in time preference suggest altering schedules of payments and other actions. Sebenius (1984) formally characterizes such optimal betting, risk sharing, and temporal reallocations. Much work on optimal contracting (e.g., Hart 1995) as well as classical economic study of gains from trade and comparative advantage directly bear on the kinds of agreements that create value on a sustainable basis. Sebenius (1992) and Lax and Sebenius (2000) offer extensive illustrations of these ‘deal-crafting’ principles in practice.

(b) Claiming Value. Crucial aspects of most negotiations, however, are primarily ‘distributive,’ ‘win-lose,’ or ‘constant-sum,’ that is, at some points in the process, increased value claimed by one party implies less for others. Several broad classes of tactics used for ‘claiming value’ in these kinds of bargains have been explored (e.g., Schelling 1960, Walton and McKersie 1965, Raiffa 1982, and Lax and Sebenius 1986). Such tactics include: shaping perceptions of alternatives to agreement; making commitments; influencing aspirations; taking strong positions; manipulating patterns of concessions; holding valued issues ‘hostage’; linking issues and interests for leverage; misleading other parties; and, exploiting cultural and other expectations. By means of these tactics, one party seeks advantage by influencing another’s perceptions of the zone of possible agreement.

3.7 Managing The Tension Between Creating And Claiming Value: The Negotiators’ Dilemma

In general, the benefits of cooperation are not fully known at the outset of a negotiation. Colloquially, the parties often do not know how large a value pie they can create. The way in which they attempt to expand the pie often affects its final division, while each side’s efforts to obtain a larger share of the pie often prevents its expansion in the first place—and may lead to no pie at all, or even to a fight. Conclusion: creating and claiming value are not in general separable processes in negotiation. This fact undermines much otherwise useful advice (that, for example, presumes ‘win-win’ situations to have no ‘win-lose’ aspects, or ‘integrative’ bargains to be unrelated to ‘distributive’ ones).

Each negotiating party tends to reason as follows: if the other parties are open and forthcoming, I can take advantage of them and claim a great deal of value; thus I should adopt a value-claiming stance. By contrast, if the other parties are tough and adopt value-claiming stances, I must also adopt such a stance in order to protect myself. Either way, a strong tendency operating on all parties drives them toward hardball. Since mutual hardball generally impedes value creation, competitive moves to claim value individually often drive out cooperative moves to create it jointly. Outcomes of this dynamic include poor agreements, deadlocks, and conflict spirals. This tendency, closely related in structure to the famous prisoner’s dilemma, was dubbed the ‘Negotiator’s Dilemma’ (Lax and Sebenius 1986, Chaps. 2 and 7). Much negotiation advice is aimed at productively managing the inherent tension between creating and claiming value, especially to do so on a sustainable basis (Lax and Sebenius 1981, Raiffa 1982).

3.8 Improving The Basis For Assessing Outcome Distributions II: Behavioral Insight

A fully rational ‘baseline’ analysis helps to understand the possible responses of a rational other side. Urging consistent, if not fully rational, behavior on the subject of one’s advice is often wise. After all, well-structured, repeated negotiations may penalize departures from rational behavior. Yet many negotiating situations are neither well-structured, repeated, nor embedded in a market context. While negotiators normally exhibit intelligent, purposive behavior, there are important departures from the ‘imaginary, idealized, super-rational people without psyches’ (Bell et al. 1988, p. 9) needed by many game-theoretic analyses.

Considerable empirical work—such as that cited above by Bazerman, Neale, Thompson, and their colleagues—offers considerable insight into how people actually behave in negotiations. Excellent reviews of the psychological side of negotiation can be found in Bazerman et al. (2000) and, focusing especially on developments on the social psychological side, in Bazerman et al. (2000). Complementing this work is the burgeoning research in experimental economics (Kagel and Roth 1995) and what Colin Camerer (1997) described as a ‘behavioral game theory.’ This work blends game-theoretic and psychological considerations in rigorous experimental settings. Two related levels are consistently important, the individual and the social:

(a) Individual negotiating behavior. As negotiators, people have different histories, personalities, motivations, and styles. Systematic characteristics of individual cognitive processes can both help and hinder the process of reaching agreement. For example, negotiators may be anchored by irrelevant information, subject to inconsistencies in the way they deal with uncertainty, hampered by selective perception, obsessed by sunk costs and past actions, prone to stereotyping and labeling, susceptible to influence tactics and manipulation by the way in which equivalent situations are framed, liable to see incompatible interests when joint gains are possible, and use a variety of potentially misleading heuristics to deal with complexity, ambiguity, and conflict.

(b) Social behavior in negotiation. In groups of two or more, especially where there is some perceived conflict, a variety of social psychological dynamics come into play that may enable or block negotiated outcomes. For example, a powerful norm toward reciprocity operates in most groups and cultures. Tentative cooperative actions by one side can engender positive reactions by the others in a cycle that builds trust over time. By contrast, social barriers can involve aspects of the interactive process that often lead to bad communication, misattribution, polarization, and escalation of conflict, as well as group dynamics that work against constructive agreements. Such dynamics may be especially pronounced when negotiations involve players of different genders, races, or cultures. Group dynamics can involve pressures for conformity, a hardening of approach by a representative before an ‘audience’ of constituents, bandwagon effects, and the individual taking cues from the behavior of others to decide on appropriate actions in the negotiation.

This experimentally based work is developing an empirical grounding for the behavioral basis of much a priori theorizing in economics and game theory. For negotiation analysis, these experimental approaches to actual behavior help to remedy a key defect of prior game theoretic work. While for the most part not prescriptively framed, this body of work also provides rigorous evidence and theory on how people in fact are likely to behave—to inform assessments of outcome distributions and against which to optimize as appropriate.

3.9 Changing The Game

Much existing theory proceeds from the assumption of a well-specified and fixed situation within which negotiation actions are taken. Yet purposive action on behalf of the parties can change the very structure of the situation and hence the outcomes. Often actions can be understood as a tacit or explicit negotiation over what the game itself will be. First investigations into this phenomenon gave rise to the terms ‘negotiation arithmetic’ or ‘adding’ and ‘substracting’ issues and parties (Sebenius 1984). This means that a perfectly legitimate and potentially valuable form of analysis may involve a search for ways to change the perceived game—even though the menu of possibilities may not be common knowledge.

Issues can be linked or separated from the negotiation to create joint gains or enhance leverage. Parties may be ‘added’ to a negotiation to improve one side’s no-agreement alternatives, as well as to generate joint gains or to extract value from others. Though perhaps less commonly, parties can also be ‘subtracted’—meaning separated, ejected, or excluded— from larger potential coalitions. For example, the Soviets were excluded from an active Middle East negotiating role in the process leading up to the Camp David accords that only involved Israel, Egypt, and the United States. The process of choosing, then approaching and persuading, others to go along may best be studied without the common assumption that the game is fully specified at the outset of analysis; Sebenius (1996) dissects and offers many examples of the process sequencing to build or break coalitions. Walton and McKersie (1965) focused on how negotiators seek to change perceptions of the game by what they called ‘attitudinal restructuring.’ In the context of competitive strategy and thinking, Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) develop a powerful, analogous logic for ‘changing the game’ that provides an overall approach and many ingenious examples of this phenomenon.

Refer back to Fig. 1, an improvement in Party One’s no-agreement alternative shifts the vertical axis to the right, leaving the bargaining set generally more favorable to that side. If Party Two’s no-agreement alternative worsens, the horizontal axis shifts down, worsening its prospects. A successful commitment to a bargaining position cuts off an undesired part of the zone of possible agreement for the party who makes it. A new, mutually beneficial option (e.g., suggestion of a contingent, rather than an unconditional, contract) causes the frontier to bulge upward and to the right, reducing the parties’ ‘conflict of interest.’ When issues change or other basic aspects of the game vary, each side’s perceptions of the basic picture in Fig. 1, the zone of possible agreement, will be transformed. These possibilities add evolutionary elements to the analysis.

3.10 The Approach As A Whole

Figure 1 can now be seen to summarize visually the extended negotiation analytic ‘model’ of possible joint action. Parties determine the axes; interests provide the raw material and the measure; alternatives to agreement imply the limits; agreements hold out the potential. Within this configuration, the process consists of creating and claiming value, which gives rise to characteristic dynamics, yet, the elements of the interaction may themselves evolve or be intentionally changed. In this sense, the elements of the approach form a logically consistent, complete whole oriented around perceptions of the zone of possible agreement.

In the skeptical view of Harsanyi, this negotiation analytic approach might boil down to

the uninformative statement that every player should maximize expected utility in terms of his subjective probabilities without giving him the slightest hint of how to choose these subjective probabilities in a rational manner. (1982)

Yet, as described above, distinct classes of factors have been isolated that appear to improve subjective distributions of negotiated outcomes. Understanding the dynamics of creating and claiming value can improve prescriptive confidence. Psychological considerations can help as can cultural observations, organizational constraints and patterns, historical similarity, knowledge of systematic decision-making biases, and contextual features. Less than full-blown game-theoretic reasoning can offer insight into strategic dynamics as can blends of psychological and game-theoretic analysis. When one relaxes the assumptions of strict, mutually expected, strategic sophistication in a fixed game, Raiffa’s conclusion is appealing: that some ‘analysis—mostly simple analysis—can help’ (1982, p. 359).

4. Conclusions And Further Directions

Naturally, there are many other related topics ranging from game-theoretic concepts of fairness for purposes of mediation and arbitration to various voting schemes. More elaborate structures are under study. For example, where negotiation takes place through agents, whether lawyers or diplomats, or where a result must survive legislative ratification, the underlying structure of a ‘two-level game’ is present (see Putnam 1988). Negotiations also take place in more complex multilevel and coalitional structures (Raiffa 1982, Lax and Sebenius 1986, 1991, Sebenius 1996). In many cases, the individual negotiation is not the appropriate unit of analysis. Instead, the study of ‘negotiation design’—for example, of international conferences, alternative dispute resolution procedures, grievance negotiation processes—seeks to maximize the chances of constructive outcomes from different structures and processes (Sebenius 1991).

While game theorists and behavioral scientists will continue to make valuable progress in understanding negotiation, a complementary prescriptive approach has been developing that conditions its prescriptions on the likely behavior of the other side, fully ‘rational’ or not, and regardless of whether the ‘game’ is fixed and entirely common knowledge. In describing the logic of negotiation analysis and the concepts and tools that can facilitate it, this discussion has not stressed the many useful ideas that arise from focusing on interpersonal and cultural styles, on atmosphere and logistics, on psychoanalytic motivation, on communication, or on other aspects. Yet because the logic is general, it can profitably accommodate insights from other approaches as well as from experience. The basic elements of this logic—parties’ perceptions of interests, alternatives, agreements, the processes of creating and claiming value, and changing the game— become the essential filters through which other factors must be interpreted for a meaningful assessment of the zone of possible agreement and its implications for the outcome.

Bibliography:

- Arrow K J, Wilson R, Ross L, Tversky A, Mnookin R H 1995 Barriers to Conflict Resolution. W W Norton, New York

- Aumann R J 1989 Game theory. In: Eatwell J, Milgate M, Newman P (eds.) Game Theory. Norton, New York, pp. 1–53

- Aumann R J, Brandenburger A 1995 Epistemic conditions for Nash equilibrium. Econometrica 63: 1161–80

- Bazerman M H, Curhan J, Moore D 2000 The death and rebirth of the social psychology of negotiations. In: Fletcher G, Clark M (eds.) Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Interpersonal Processes. Blackwell, Oxford, UK, pp. 196–228

- Bazerman M H, Curhan J, Moore D, Valley K L 2000 Negotiations. Annual Review of Psychology. Annual Reviews, Palo Alto, CA

- Bazerman M H, Neale M A 1992 Negotiating Rationally. Free Press, New York

- Bell D E, Raiffa H, Tversky A 1988 Decision Making: Descriptive, Normative, and Prescriptive Interactions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Brandenburger A M, Nalebuff B J 1996 Coopetition. Currency Doubleday, New York

- Camerer C F 1997 Progress in behavioral game theory. Journal of Economic Perspectives 11(4): 167–88

- Harsanyi J C 1982 Subjective probability and the theory of games: Comments on Kadane and Larkey’s paper. Management Science 28(2): 120–4

- Harsanyi J C, Selten R 1988 A General Theory of Equilibrium Selection in Games. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Hart O 1995 Firms, contracts, and financial structure. Clarendon Lectures in Economics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Kadane J B, Larkey P D 1982 Subjective probability and the theory of games. Management Science 28(2): 113–20

- Kagel J, Roth A E 1995 The Handbook of Experimental Economics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Keeney R, Raiffa H 1976 Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Tradeoffs. John Wiley, New York

- Lax D A Sebenius J K 1981 Insecure contracts and resource development. Public Policy 29: 417–36

- Lax D A, Sebenius J K 1986 The Manager as Negotiator: Bargaining for Cooperation and Competitive Gain. Free Press, New York

- Lax D A, Sebenius J K 1991 Thinking coalitionally: Party arithmetic, process opportunism, and strategic sequencing. In: Young H P (ed.) Negotiation Analysis. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI, pp. 153–93

- Lax D A, Sebenius J K 2000 Basic dealcrafting: Principles for creating value in negotiation (under review). Harvard Business School, Boston, MA

- Luce R D, Raiffa H 1957 Games and Decisions. Wiley, New York

- Mnookin R H, Peppet S R, Tulumello A S 2000 Beyond Winning: Negotiating to Create Value in Deals and Disputes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Neale M A, Bazerman M H 1991 Cognition and Rationality in Negotiation. Free Press, New York

- Putnam R D 1988 Diplomacy and domestic politics: The logic of two-level games. International Organization 4Z: 427–60

- Raiffa H 1982 The Art and Science of Negotiation. Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Raiffa H 1997 Lectures on Negotiation Analysis. PON Books, Cambridge, MA

- Rothschild M, Stiglitz J E 1970 Increasing risk, I: A definition. Journal of Economic Theory 2: 225–43

- Rubinstein A 1991 Comments on the interpretation of game theory. Econometrica 59: 909–24

- Schelling T C 1960 The Strategy of Conflict. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Sebenius J K 1984 Negotiating the Law of the Sea: Lessons in the Art and Science of Reaching Agreement. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Sebenius J K 1991 Designing negotiations toward a new regime: The case of global warming. International Security 15 (4): 110–48

- Sebenius J K 1992 Negotiation analysis: A characterization and review. Management Science 38(1): 18–38

- Sebenius J K 1996 Sequencing to build coalitions: With whom I should talk first? In: Zeckhauser R, Keeney R, Sebenius J K (eds.) Wise Decisions. Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 324–48

- Sebenius J K 2000 Deal-making essentials: Creating and claiming value for the long term. Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, Item 2-800-443

- Thompson L 2001 The Mind and Heart of the Negotiator, 2nd edn. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

- Tirole J 1988 The Theory of Industrial Organization. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- von Neumann J, Morgenstern O 1944 Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Walton R, McKersie R 1965 A Behavioral Theory of Labor Negotiations. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Young H P (ed.) 1991 Negotiation Analysis. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- Zeckhauser R, Keeney R, Sebenius J K (eds.) 1996 Wise Decisions. Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, MA