View sample Economic Statistics Research Paper. Browse other statistics research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

‘Economic statistics’ in the widest sense of the term refers to those statistics the purpose of which is to describe the behavior of households, businesses, public sector enterprises, and government in the face of changes in the economic environment. Accordingly, economic statistics are about incomes and prices, production and distribution, industry and commerce, finance and international trade, capital assets and labor, technology, and research and development. Nowadays it is customary to include under economic statistics estimates of the value and quantity of stocks of natural assets and measurements of the state of the physical environment.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Economic Statistics And Official Statistics

In its strict sense the term economic statistics has a narrower scope as a distinction is drawn between economic statistics and economic accounts (as in the national or international accounts). Some statistics occupy a gray area—between social and economic statistics. They comprise measurements that play a role in describing social conditions and are used intensively in the making of social policies but at the same time relate intimately to the economic fabric of society. Examples are the statistics on income distribution commonly used for the measurement of poverty, the occupational make-up of the labor force, the expenditure patterns of households, and the structure of their income. For purposes of the present article the term ‘economic statistics’ excludes the national accounts but includes the statistics that are simultaneously used for economic and social purposes. Most of the references in this research paper apply to official statistics, i.e., those statistics that are either produced by government statistical agencies or by other bodies but are legitimized by being used by government. The usage adopted corresponds to the way in which government statistical offices are commonly organized.

2. Directly Measured Statistics And Derived Statistics

The term economic statistics is usually applied to statistics derived from direct measurement, i.e., either from surveys addressed to economic agents or from official administrative procedures that yield numerical data capable of being transformed into statistics. For example, the statistic on the national output of cement is usually derived by directly asking all (or a sample of) cement producers how much cement they produced over a defined period. The statistic on how many jobs were filled during a given period may be derived from the social security forms that employers are requested to send to the social security administration from time to time. This is different from the way in which the economic accounts of the nation are derived.

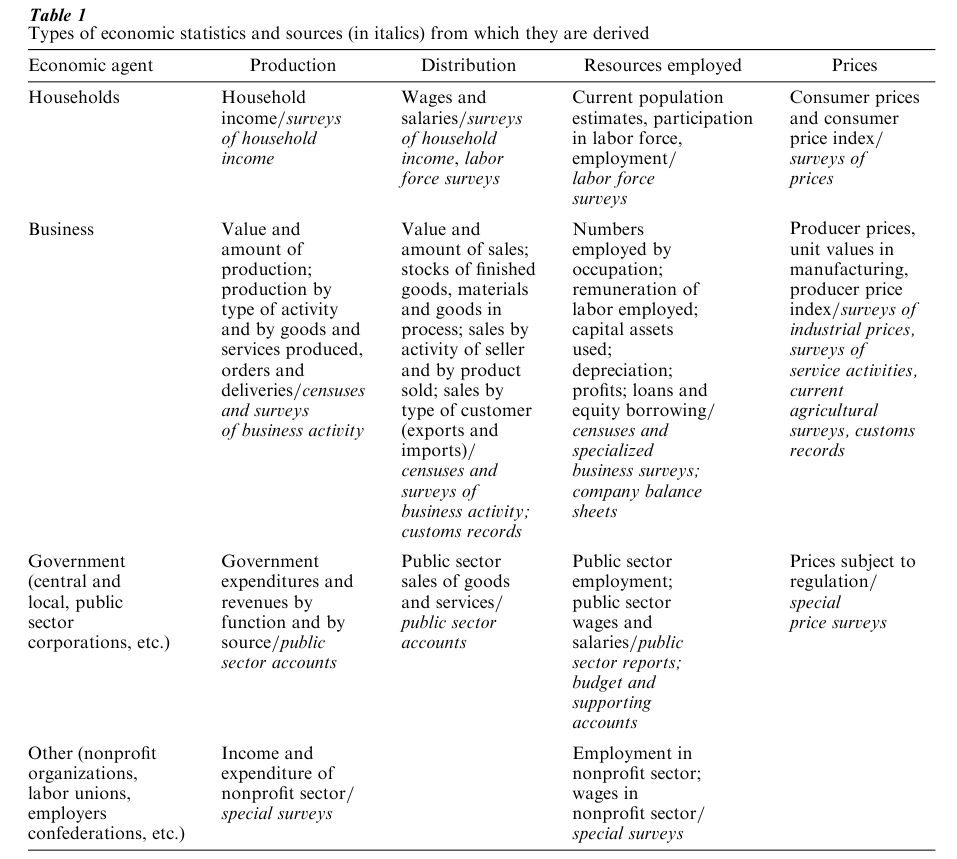

These are formed by combining all the existing economic (or basic) statistics through an interrelated system of accounting identities and from those inferring identity values that may not be available directly. They are also a means of assessing the strengths and weaknesses of economic statistics by noting how close they come into balance when the system of identities is applied to them. In other words, economic statistics are the raw material on the basis of which the economic or national accounts are compiled. The compilation of the national accounts in addition to summarizing and systematizing economic statistics plays the important role of showing up gaps in the range of economic statistics required to describe the functioning of the economic system (Table 1).

2.1 Economic Statistics And Business Statistics

The kernel of economic statistics is formed by statistics related to business and derived from questionnaires addressed to business, from questionnaires addressed to business employees, or from official records which businesses create in their dealings with government. Such statistics include descriptions of the business activity (what does the business produce, how does it produce it, for how much does it sell, what is the surplus generated by the sale once materials and labor are paid for, etc.) as well as of the nature of the factors engaged in production (structures and equipment used in production by type; labor employed by type of skill and occupation), and in addition statistics on the type of customers who purchase goods and services from businesses.

3. How Economic Statistics Are Measured

In spite of the increasing popularity of using administrative records as sources to generate economic statistics, on the whole, economic statistics are compiled mostly from surveys addressed to business. Generally speaking, the surveys consist of a list of respondents, a formal questionnaire—which can be used as basis for a personal interview (or an interview by telephone or Internet), a procedure followed when dealing with exceptional cases (not finding the right person to whom the questions should be addressed, finding that the business is not in the expected activity, or that the answers are incomprehensible or contradictory)—and a set of steps designed to aggregate individual answers so as to produce statistical totals, averages, or measures of distribution.

3.1 Problems Of Defining What Is A Business

Part of the process of conducting a business survey consists in locating the addressees—either all the addressees in the survey universe if the survey is of a census type or some of the addressees if it is a sample survey. In either case two issues must be settled beforehand: (a) that all the addressees conduct the activity they are supposed to and (b) that there is no one else who conducts the targeted activity and has been left out. A related question has to do with what is a business. The ‘business’ can be defined as the entity that is liable under the law to pay taxes; that has a management capable of deciding its scale of operations and how those operations should be financed; and that inter alia conducts the activity that is germane to the survey. An alternative definition is one that seeks that part of the business (and only that part) that engages in the target activity directly and excludes all other parts of the business. In either case it is important that the respondents to the survey understand the scope of the questions and are capable of answering them out of records available to the business’s management.

3.2 Business Records

Businesses tend to keep all the records they require to ensure informed management in addition to what they have to keep in order to comply with tax authorities and any other regulatory bodies that affect them. Usually those records fall into five categories: tax related; social insurance; engineering records on the performance of physical production; personnel and safety records; and environmental records if the productive activity is of sufficient importance and of a kind that may detrimentally affect the physical environment. The efficiency of statistical surveys is measured partly by the ability of the statistical agency to request that information, but mostly by that information which is readily available from the records the business tends to keep anyway.

3.3 Household Surveys

Usually the major surveys addressed to households include a survey of households and how their members relate to the labor force and a survey of family income and expenditure. The former is the basis upon which statistics on the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed are calculated. The latter usually produces two key statistics: income distribution and structure of household expenditure. The latter is used to determine the various proportions of expenditure, which in turn are used in the compilation of the consumer price index. The surveys about household behavior—variation in the structure of expenditure and savings according to income, location of residence, family size, and age distribution—also provide key social statistics.

3.4 Public Accounts And Administrative Records

There are at least two categories of records that make explicit survey taking redundant: reports on public accounts and administrative registers created as a result of regular and comprehensive administrative procedures. The two have different properties. The accounts of the public sector (and of para-public enterprises such as nationalized industries or public corporations) are usually made available to the public as a means of displaying transparency and accountability. If the statistical requirement is limited to the displaying of aggregate information, what is published is usually sufficient as a description of the income, expenditure, and balance sheet of all public sector entities. In addition, all operations relative to the collection of taxes generate comprehensive records, susceptible to replace statistics to the extent the latter target the same variables. For example, the collection of income tax generates statistics on the income structure of all households (or individuals) liable to pay tax. The collection of VAT-type taxes generates records on the amount of sales, the nature of the seller, and in many cases the broad economic sector to which the buyer belongs. Social security records tend to generate information on the nature of the worker from whom amounts for social insurance are withheld, their place of work, the hourly, daily, or weekly remuneration that serves as a basis for the estimation of the amount withheld, etc. And of course, the oldest and most universal administrative operation of all—that connected with the activity of customs administrations—generates comprehensive information on the value, composition, conveyance used, origin, and destination of merchandise that either enters or leaves the national territory. This information, also known as merchandise exports and import statistics, is to be found amongst the earliest collections of numerical data of relevance to the administration of a country. To the extent that these administrative records are accessible to the compilers of statistics they tend to constitute acceptable replacements for estimates derived from surveys or from censuses.

4. Economic Classifications And Conceptual Frameworks

Economic statistics—like any other kind of descriptive statistics—are usually presented within the framework of standard classifications. In addition to geographic classifications, the most popular of these classifications are the Standard Industrial Classification (the SIC, or in its international version, the ISIC) and the Standard Product Classification (the SPC or, in its international version, the Standard International Trade Classification or currently the Central Product Classification). The SIC refers to the activity (or production technique) used to produce a specified list of goods and services. Similar (or homogeneous) production techniques are grouped into industries. The overall result of these groupings is a classification that views economic activity from the supply side. The SPC groups goods and services by their intrinsic characteristics rather than by the way in which they were produced. It is a classification that views the results of economic activity from the demand side. The use of international classifications is vital to ensure intercountry comparability of economic statistics.

The history of international cooperation in economic statistics is inextricably bound with the history of the two major economic classifications. Thus, the United Nations Statistics Commission, at its first meeting immediately after the end of World War II, commissioned the Secretariat to produce a classification of economic activities and shortly afterwards requested the development of a classification of the goods that entered into international exchanges (imports and exports). The Committee on Statistics of the League of Nations had worked on an initial version of such a classification. Almost immediately after the war the Statistics Commission approved the International Standard Industrial Classification of Economic Activities (ISIC) and the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC). Today, both classifications are into their fourth version (ISIC Rev. 3 and SITC Rev. 3, respectively).

Currently, the economic statistics of the members of the European Union and of many central and eastern European countries are classified by the NACE (Nomenclature des Activites economiques dans les Communautes Europeennes). The three North American countries have their own system of economic classifications (North American Industrial Classification System—NAICS). Most other countries use one or another of the various versions of the ISIC.

The classification of goods was taken over by the body created to co-ordinate the activities of customs administrations worldwide (the Customs Co-ordination Council) and ended up as the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS). As such it has been adopted for international trade statistics by the overwhelming majority of countries. Indeed, a number of them use the same classification for purposes of presenting their commodity output in the context of their industrial statistics. The requirement to develop an international classification of services prompted—again at the request of the United Nations Statistical Commission—the development of the Central Product Classification (CPC) which is being increasingly used to compare statistics on international trade in services with the internal production of and commerce in services.

4.1 Other Classifications

These apply to a variety of economic statistics but they (with the possible exception of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO)) are neither as well developed as the ones on activity and product nor are they at this stage the subject of international agreement. There are several examples of such classifications. In the case of capital assets there is still the question of whether a classification of assets ought to be embedded in the standard classifications of goods or whether it should be sui generis. There is no suitable classification of intangible assets. In the realm of labor inputs, recent innovations in the contractual relationship between employers and employees have produced a variety of forms of employment, none of which has so far found its way into an accepted classification.

4.2 Conceptual Frameworks

The conceptual framework for economic statistics is a hybrid, somewhere between business accounting and the system of national accounts. But, because economic statistics are the prime ingredient for the compilation of the national accounts, an explicit reconciliation between the former and the latter is required. Current trends suggest that because of pressures to keep government generated paperwork down, economic statistics tend to follow the patterns of business records. Where required, supplementary information is collected so that the basic statistics may be reconciled to the requirements of the national accounts compilers. But typically the necessary adjustments are conducted within the statistical agency. This is usually the case for key balances such as profits.

5. The Evolution Of Economic Statistics As A System

The traditional manner in which economic statistics were derived was by the periodic taking of an economic census. Indeed in earlier times the census of population was taken together with the economic census. More recently, the economic census is addressed at businesses and retrieves information on their activity, location, legal form of organization, and on how many and what kind of people they employ. Supplementary information is usually obtained through lengthier questionnaires addressed not to all businesses but rather to a selection, usually above a certain size but sometimes to a randomly selected fraction of all those in the scope of the census.

5.1 Censuses And Registers

Economic censuses have become steadily less popular, largely due to their cost, the time it takes to process them, and the fact that, because of rapid changes in the size, make up, and even activity of businesses, census information loses much of its value shortly after it is compiled. Instead, there has been an equally steady increase in the popularity of registers of businesses, usually derived from administrative data and used for much the same purposes as censuses but updated far more frequently. Indeed, in a number of cases, the introduction of new administrative procedures connected with tax gathering has been managed bearing in mind possible requirements of importance to the government’s statistical agency.

The lists of businesses derived from administrative or tax-gathering procedures, commonly referred to as ‘business registers,’ are used mostly in two modes: as sampling frames and as a basis for indicators of economic performance such as ‘net business formation’ (the difference between the numbers of businesses created and the number of businesses closed down in a given period of time). As sampling frames, business registers are invaluable to support ad hoc inquiries into the state of the economy, usually conducted by contacting a randomly chosen group of businesses and gauging the opinion of their chief executive officers.

There are several requirements that must be satisfied for the modern approach to the compilation of business statistics to work. In particular, the source of information for the register must be comprehensive; it must be kept up to date as a result of the administrative procedures on which it is based; and the statistical agency must have unrestricted access to the source. The benefits that accrue to a statistical office from a business register are that: (a) it can dispense with the task of conducting a periodic census; (b) it can conduct a coherent set of sample surveys and link the resulting information so as to form a composite picture of the economy and its performance; and (c) it can control the paper burden that it imposes on individual business respondents through its multiple surveys.

5.2 Applications Of Business Registers

Business registers are maintained at two distinct levels. There is a list of all businesses through their registration with some government department (usually the tax authority). This list conveys no more than there is a possible business behind a tax account. The physical counterpart of the tax account is usually determined by direct contact once it is established that the business is more than just a legal entity. The relationships between businesses as legal entities and the establishments, mines, mills, warehouses, rail depots, etc. that comprise them are a source of interesting information, but they are also the most difficult part of the management of a business register.

6. Current Economic Indicators

Under the impulse of macroeconomic stabilization policies and the belief in policy makers’ ability to fine tune effective demand, the early 1960s saw a worldwide push to develop current economic indicators of demand by sector. A great deal of the empirical work had been done in the US, spearheaded by the National Bureau of Economic Research and resulting in a classification of short term economic statistics according to whether they lead, coincided, or lagged behind the ‘reference’ economic cycle. Most attention was placed on the performance of manufacturing industry, particularly on the output of equipment for of fixed investment as well as for export; on the construction of plant and of other nonresidential structures; and in general on leading indicators of capital formation. At the same time considerable effort was made to improve the reliability and the timeliness of the key variables for purposes of economic stabilization: the rate of unemployment and the change in the consumer price index. Lastly, the balances in the main markets of the economy were looked at through quarterly national accounts, which in turn demanded major developments in the quality and the quantity of basic economic statistics.

7. Today’s Array Of Economic Statistics

In today’s array of economic statistics the following would be the expected components in the more advanced statistical agencies: (a) statistics on the structure of the economy derived from either an economic census or from administrative data complemented by a survey on structural data (type of activity, breakdown of production costs, capital stock etc.); (b) exports and imports of goods and services, with the goods part broken down by commodity, country of origin and destination; (c) producer and consumer prices and indexes thereof; (d) short term indicators of economic change such as order books, deliveries of manufacturing goods and stocks thereof; (e) monthly physical output of key commodities and an index of industrial production; (f ) business balance sheets (income, profit and loss, financial) and employment and unemployment as well as household income and expenditure. In addition, a statistical version of the accounts of the public sector would be an expected component.

In order to support these statistics, statistical agencies would maintain an up-to-date version of a classification by economic activity, usually an internationally agreed classification with a national supplement, and a classification of goods and services. They would also have their own or an international version of the classification of occupational employment.

Bibliography:

- Cox B et al. 1995 Business Survey Methods. Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics. Wiley, New York

- ISI, Eurostat, BEA 1996 Economic Statistics, Accuracy, Timeliness and Relevance. US Department of Commerce, Washington, DC

- Statistics Canada 1997 North American Industry Classification System. Statistics Canada, Ottawa

- Turvey R 1989 Consumer Price Indices, an ILO Manual. International Labor Office, Geneva

- United Nations 1990 International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities, Statistical Papers Series M No. 4 Re . 3. United Nations, New York

- United Nations 1991 A Model Survey of Computer Services, Statistical Papers Series M No. 81. United Nations, New York

- United Nations 1993 System of National Accounts. United Nations, New York

- United Nations 1997 Guidelines on Principles of a System of Price and Quantity Statistics, Statistical papers Series M No. 59. United Nations, New York

- Voorburg Group 1997 Papers and Proceedings. United Nations Statistical Commission, New York