View sample economics research paper on labor market. Browse economics research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Work is a part of life for almost all people around the world. Though the types of work people do and the conditions under which that work is done vary endlessly, people get up each morning and choose to use their human capital in ways that generate some sort of productive good or service or that help prepare them to be productive economic citizens in the future. Some of this work is done in the privacy of the home, where beds are made, children are raised, and lawns are mowed. While this unpaid productive activity is essential to a well-functioning economy, this research paper addresses work time and skills that are sold in markets in exchange for wages and other compensation.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The purpose of this research paper is to explore the unique nature of labor markets and to consider how these markets will evolve in response to changes in the nature of the work people do over time. Use of labor, like any economic resource, has to be considered carefully in light of productivity and opportunity costs. Though many factors affect this decision-making process, in most cases labor is allocated by market forces that determine wages and employment.

That said, several characteristics of labor as a resource create complexities. First, the demand for any type of labor services is derived from, or dependent on, the demand for the final product that it is used to produce. This means that highly trained and productive workers are only as important in production in an economy as there is demand for the product they produce. Second, because labor cannot be separated from the particular persons who deliver the resource, the scope of responses to labor market decisions is broad and affects outcomes in significant ways. The sale of labor services generates the majority of household income around the world—income that is used to sustain workers and their families. This means that labor markets determine, to a large extent, what resources a household has available and thus the quality of life for the members of the household. Decisions become very complex when workers and their families begin considering not only job market choices but also premarket education and training that might be required to prepare individuals for particular occupations.

Theory of Labor Market Allocation

As with all markets, buyers (employers or contractors) and sellers (employees) communicate their needs and offers with one another and exchange labor services for wages and other compensation. Some important assumptions underlie this model. First, assume that the wage and other monetary compensation is the most important determinant of behavior. This allows the construction of a model that has wages on the y-axis and quantity exchanged on the x-axis. Everything else held fixed, buyers and sellers will respond most directly to price signals exchanged between the two groups. Second, assume that workers are somewhat homogeneous—that is, that workers can be easily substituted for one another in any particular market. (Differences across workers will be explored later in this research paper.) Third, assume that workers are mobile and can move to places where there is excess demand for labor with their particular skills and away from places where there is excess supply of labor with their particular skills. Finally, assume that wages are flexible; they can move up or down in response to market signals.

Given these assumptions, the next step is to consider the behavior of buyers and sellers in what can be referred to as perfectly competitive markets for labor. In such markets, many relatively small employers hire relatively small amounts of labor; neither employers nor employees acting alone are a significantly large enough share of the market to be able to affect market wages. An example of this might be a college in New York City that hires administrative assistants. There are many such assistants in the market looking for jobs and many alternative employers, so both buyers and sellers have to accept the going wage for such work.

Labor Demand

Employers seek workers based on workplace needs and based on the demand for the good or service being produced. In addition to the market wage, employers consider the productivity of labor, the ability to substitute across other inputs in the production process, and the prices of other inputs when making hiring decisions.

Labor productivity is determined by a variety of factors, including human capital investments made by the worker himself or herself or the employer, skills and talents, and the quantity of capital and technology that the worker has at his or her disposal. As might be assumed, the greater the investment made in an individual worker, the greater his or her productivity. Like with any other investment opportunity, the investor spends money now (e.g., gets a master’s degree in social work or an MBA), hoping to eventually reap the benefits, in terms of greater income earning potential, in the future.

Substitution of inputs can be easy or difficult, depending on the production process being considered. For example, in an accounting firm, junior and senior partners might be equally productive (though not, perhaps, in the minds of important clients). Junior and senior partners can be relatively easily substituted for one another as tax forms are prepared. However, in a telemarketing firm, each caller needs to have his or her own phone. If an employer hires more callers but buys no more phones, no additional calls will be made. It might be easy to substitute junior for senior account managers, but it is impossible to substitute callers for telephones.

Understanding these sorts of trade-offs is very important for a firm; as the prices of inputs (junior and senior account managers or callers and phones) change, the employer will want to shift the input mix so that output is produced as efficiently and cheaply as possible. However, depending on the degree of substitutability, the changing input prices will create incentives to use more of the input that is becoming relatively cheaper and less of the input that is becoming relatively more expensive.

In spite of these other factors and their importance, firms tend to hire a greater number of hours or workers in the market, and more firms become buyers in a given market, as wages and compensation fall—everything else held constant. This empirically based conclusion is consistent with the law of demand. There is an inverse relationship between the quantity of labor demanded in a market and the price of labor in that market.

Labor Supply

Workers seek jobs based on their own skills and talents and based on the variety of factors that help to determine their income needs. Preferences over alternative jobs are important—some workers seek jobs that provide them with a sense of pride, accomplishment, and satisfaction. In other cases, workers have a preference for maximizing their own personal income, and so they search for jobs that are high paying, regardless of their other characteristics. Happily, the diversity of jobs combined with the heterogeneity of workers and their preferences generates labor markets that provide incentives for employers and for workers. Jobs that are distasteful to many workers for one reason or another (washing windows on skyscrapers or cleaning out pig sties) attract workers who are less averse to the negative aspects (heights or smells), and/or the work commands wage premiums that accrue from smaller pools of available workers. Thus, workers sort toward jobs that best meet their particular preferences and monetary needs.

Most often, workers consider the expected wage to be a key factor, if not the key factor, in determining what jobs to seek and accept. For some jobs where compensation is based on productivity (sales commissions, as an example, for real estate agents), there can be significant wage uncertainty. This uncertainty means that a job with a high wage might not be as appealing as a job with a lower wage that offers more security. For example, a worker might put her desire to be a professional tennis player aside in favor of the more stable employment position of a bookkeeper if she has elderly parents who need her care. High wages alone are not enough to attract workers to jobs; it is the entire employment package, and the level of employment and compensation risk, that must be considered when choosing a labor market to enter.

Given these other factors and their importance, workers tend to offer more hours in the market, and more workers enter a given market, as wages and compensation rise— everything else held constant. This empirically based conclusion is consistent with the law of supply that governs most market settings. There is a direct relationship between the quantity of labor supplied to a market and the price of labor in that market.

Market Equilibrium

When economists speak of equilibrium, they are using the term as any other scientist would—as a state of the world that, once reached, will not change unless a significant force acts upon it. Equilibrium price and quantity in a labor market is reached when there is no further tendency for wages or quantity of labor bought and sold to change, unless there is a change in the market that affects the demand curve or the supply curve.

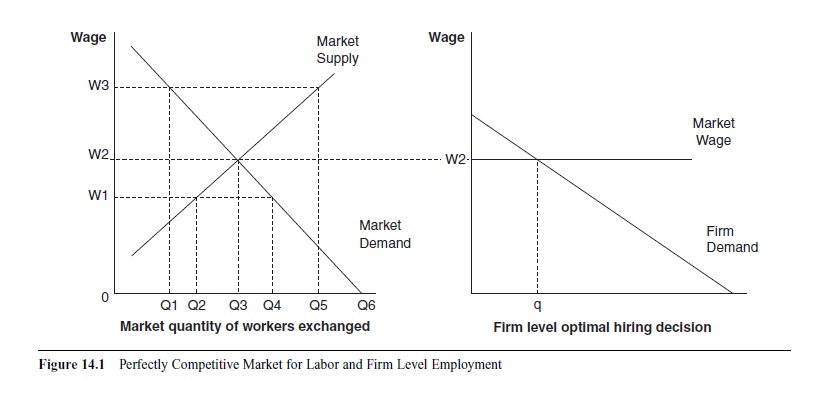

Consider Figure 14.1. At W2, Q3 workers are demanded, and Q3 workers are supplied. Note that if the wage is W1, the quantity of workers demanded is greater than the quantity of workers supplied. There is a shortage of labor; the quantity of labor employers are willing and able to hire is greater than the quantity of labor people are offering for sale. Wages will rise as firms outbid one another to attract the workers they need. On the other hand, at W3, the quantity of workers demanded is less than the quantity of workers supplied. There is a surplus of labor; the quantity of labor employers are willing and able to hire is less than the quantity of labor people are offering for sale. Wages will fall as workers have to accept lower wages if they hope to gain employment. Thus, the only point at which wages and employment will not be under pressure to rise or fall is at W2, and it is defined as the current equilibrium in this market.

Note several things about this equilibrium price and quantity. First, economists often refer to this point as market clearing; this means that everyone who wants to buy labor at this wage rate can and everyone who wants to sell labor at this wage rate can. There is no excess supply or excess demand at the equilibrium wage. Second, although the market clears at this point, it is not necessarily a “good” wage and quantity combination. There are people in the market who would like to purchase labor at wages below W2 who cannot do so (Q3-Q6), and there are people in the market who would like to supply labor at wages above W2 who cannot find jobs (Q3 and above). They are left out of the market under these supply and demand conditions, and that might not be good for the workers or their families if they are unemployed or for the firms if they need workers to produce output to sell in the marketplace. Finally, note that some markets are very volatile, and so even though there are equilibrium wages and quantities exchanged, supply and/or demand are shifting significantly and often. For example, consider dockworkers. When a ship arrives at a port, the workload is heavy and demand for workers is high. However, when there are no ships in port, either because demand for the goods coming in has fallen or because supply has been affected by weather or other factors, demand for workers is low or nonexistent. These sorts of big swings in demand for workers can lead to significant wage volatility. It will become clear that unique sorts of contractual arrangements will be required to be sure that workers will be available for these types of tasks.

Imperfect Competition

The perfectly competitive market model applies when there are many, many workers in a market that also supports many, many employers. However, what if this is not the case? What if there is a single large employer that dominates the market for a particular type of labor? For example, major league baseball employs almost all of the professional baseball players in the United States. How does this situation impact the distribution of resources in a labor market? How will the equilibrium wage and quantity of labor exchanged be different under these circumstances?

Figure 14.1 Perfectly Competitive Market for Labor and Firm Level Employment

Monopsony power refers to the ability of a single employer to control the terms of employment for all of, or a portion of, its workforce. The first significant examples of monopsonies emerged during the industrial revolution when factories (coal mines, steel mills, etc.) opened in small towns; the mine or the factory became the most significant employer in the town or local area, and workers had few other job opportunities. Because workers had limited alternative employment options, the firms were able to pay lower wages and exploit the workforce in a variety of other ways. In some cases, firms also established company stores that became monopolies in the provision of goods and services. Thus, the workers were subject to monopsony power in the terms of their employment and monopoly power in the markets in which they spent their income.

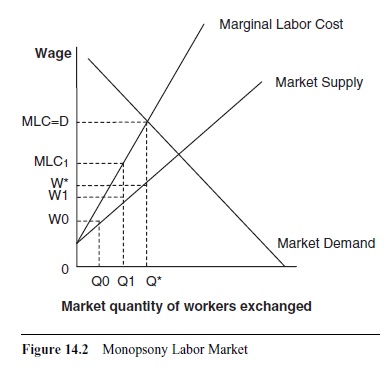

In response to this exploitation of workers by monopsonistic employers, workers formed unions—collective organizations of sellers that formed to gain some bargaining power in negotiations with their employers over the terms of their contracts. These unions gained legal status in most countries around the world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, in some countries that are at the earlier stages of industrialization, unionization and other types of worker movements may still be illegal or nonexistent. Consider the model in Figure 14.2. The labor demand curve, described as for the perfectly competitive market in Figure 14.1, depends on the output market in which the firm sells its final product and the productivity of its workers. However, now rather than paying a wage imposed by the free marketplace, firms have the ability to set wages at the lowest level possible. Firms are not assumed to be wage discriminators; all workers are paid the same amount per quantity supplied. (Wage discrimination is possible but is not considered here.) The key is that firms pay the lowest price they possibly can, given by the market supply curve at the optimal level of employment, and then increase the wage for all by the smallest amount possible, moving up the supply curve, when employment is increased by a small amount.

Figure 14.2 Monopsony Labor Market

Figure 14.2 Monopsony Labor Market

Using Figure 14.2, suppose the current level of employment is Q0 and the wage is W0. If the labor monopsonist chooses to increase employment by one worker, labor costs increase by the amount of the wage payment to the new worker but also by the increased wage that has to be paid to all of the existing workers. Firms cannot discriminate and so must pay the same higher wage to all workers of the same type if a marginal worker is to be hired. Thus, the increase in the costs of employment to the firm in this market when a marginal worker is hired is greater than just the wage paid to the new worker; the marginal labor cost (MLC) of hiring one additional unit of labor is greater than the wage paid to that one marginal unit. The MLC curve lies everywhere above the supply curve because at any quantity of labor, MLC is greater than the wage.

In these imperfectly competitive markets, firms choose to hire where MLC intersects the demand curve, at MLC = D and Q*. This means the amount of money that comes into the firm when a marginal unit of labor is hired is just equal to the amount of money that goes out when the marginal unit of labor is hired. However, firms are able to pay a wage that is lower than the value of the marginal worker to the firm (W*). This wedge between the value of the worker to the firm and the wage paid has ignited anger among philosophers and workers around the world for hundreds of years. They read Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto and believe in the labor theory of value, that the entire value of a final good or service should accrue to the labor inputs that were used to produce it. This alternative to a market model of wage determination had tremendous impacts on economies around the world during the twentieth century and will continue to affect decisions regarding trade-offs between the efficiency and equity of economic outcomes for years to come.

Applications and Empirical Evidence

There are endless applications of labor market theory to be found in economies around the world. Three of the most significant will be considered here, but the ideas presented can be adapted to fit a variety of other circumstances.

Economics of the Household or the New Home Economics

Increased labor force participation rates for women around the world, particularly in industrialized countries, were a major feature of the twentieth century. In addition to changing the landscape of labor markets, this phenomenon has had tremendous impacts on households, on families, and on the ways that cultures proscribe the management of unpaid work within the household. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1900, 20% of women in the United States participated in the labor force (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1975). By 2000, that percentage had increased to 59.9% (International Labour Office [ILO], 2003). By contrast, in 2000 the female labor force participation rate was only 16.3% in Pakistan, 39.6% in Mexico, and 49.2% in Japan. These differences are significant and reflect alternative cultural norms and government support for medical care, child care, and other such programs that make it easier for women to enter the workforce.

In the United States, women began entering the labor market in significantly greater numbers during World War II to replace male employees who were fighting overseas. However, at the end of the war, women were forced out of employment in many cases by men, who were assumed to be heads of households, returning from active duty. It was not until the 1960s that women began to make their way back to work. Many factors can account for this, including the development of safe and reliable birth control, increased access to college and university education for women, declines in birthrates, and increases in divorce rates.

Economists like Gary Becker and Jacob Mincer, who first began investigating family decision making in the early 1960s, used models of international trade to explain how the law of comparative advantage applied equally well to household specialization and trade and to international specialization and trade. These models showed that, when the opportunity costs differed for family members producing the same goods, household production would be more efficient if each member produced those goods and services that they produced with lowest opportunity costs. Trade within the household ensured that each member would be able to consume a mix of goods and services.

This model helped provide some insights into the nature of household production, but it immediately led to alternative explanations and theories. Economists like Barbara Bergman and Julie Nelson have cited alternative explanations for the household structure that we most commonly see around the world—the male head of householder working in the labor market and supporting the efforts of other family members who are engaged in production within the household or human capital formation. One explanation might be found in bargaining models, which describe women and children who are less powerful in the household due to the absence of monetary income or having to depend on an altruistic head of household for economic resources. This means that the typical household structure is the result of differences in access to resources and bargaining power rather than any sort of efficiency in allocation processes or gains from trade explanation. In other cases, the household resource distribution system could be modeled as a Marxist process of exploitation; the “haves” (aka workers in the labor market) exploit the “have nots” (aka nonmarket workers in the household) to pursue their own self-interest and personal resource accumulation. These alternative models of resource allocation within the household have become increasingly important as economists have tried to better understand the nature of social problems like discrimination and domestic abuse.

Differences in Wages Across Occupations

In most economies, on average, doctors make more money than nurses, highway construction workers make more money than assembly line workers, plumbers make more money than administrative assistants, and stockbrokers make more money than teachers. Why is there so much wage dispersion in labor markets? What causes wages to vary so significantly across different types of workers and occupations?

There are a variety of answers to this question, but the key is that wages are often used to compensate for other aspects of a job that make it more or less attractive. For example, consider two jobs that are very similar in many ways: doctor and nurse. They both work in the same offices or hospitals, they both care for patients who have some form of health issue, and they both report to the same board of trustees or corporate owners of a health care facility. Because of these similarities, one might make an argument that the pay for these two occupations should be equal—what accounts for the differential in wages?

The key here lies in the significant difference in education and training required by doctors compared to nurses, in most cases. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, it takes 11 years of higher education, on average, to become a doctor, while the average registered nurse has a 4-year bachelor’s degree (U.S. Department of Labor, 2008-2009a, 2008-2009b). If people are to find the additional time spent in education and training, not to mention the added responsibility of being a doctor rather than a nurse, worthwhile, there must be some hope of a future payoff. It is true that many doctors find great satisfaction in helping patients, but additional pay into the future must be expected in order to repay student loans and to cover the opportunity cost of lost wages during long years in school. This sort of return to education and training compensates for an aspect of becoming a doctor that is negative and that would discourage entrants from pursuing the occupation.

In another example, highway construction workers versus assembly line workers, compensation is provided for risk of injury on the job. Though both these occupations typically require dexterity, strength, and concentration, the highway construction worker faces a much greater risk of injury while at work than does the assembly line worker. According to a brief prepared by Timothy Webster (1999) for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of injuries on the job for workers in construction and manufacturing jobs were almost equal; however, construction workers were almost four times as likely to die on the job than manufacturing workers. In this case, the higher wages paid to construction workers, who have similar levels of education and training as manufacturing workers, compensates for the much higher risk of death while on the job.

In other cases, higher wages compensate for unpleasantness on the job. Some of the most unpleasant working conditions can be found in meatpacking plants or in other food processing plants. Steel mills are notoriously hot and loud. Offshore oil drilling requires long periods away from home. Work in chemical plants may increase the risk of illness or cancer. All of these negative aspects of jobs lead to lower supplies of labor at any wage rate and hence higher wages.

One last aspect of an occupation to be considered is wage risk. Though two jobs, stockbroker and college professor, might have the same expected wage, the level of risk and uncertainty can be very different. For example, according to the 2005-2006 annual survey by the American Association of University Professors (2006), the average salary for a full professor was $94,738; typically a full professor has job and income security guaranteed by tenure but little hope of additional compensation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics cites the average salary for financial services sales agents in 2006 to be $111, 338; the bonuses and extra compensation available to such workers runs into the millions of dollars in some cases, but as we saw during 2008, job security in such positions is nonexistent when financial services industries feel the sting of recession (U.S. Department of Labor, 2007). Wage and employment risk must be compensated for by the prospect of big wins and large bonus plans.

Given the model of labor markets presented earlier, it is clear that interaction between the demand for labor and the supply of labor determines the equilibrium wage to be paid to workers. The sorts of job characteristics described above all affect the size of the applicant pool available to take on certain types of jobs and hence the position of the labor supply curve.

Unemployment

Though labor markets clear when quantity demanded is equal to quantity supplied, as described above, there are workers who are still seeking to work once the market clears, just at wages that are above market equilibrium. When people are actively seeking work but cannot find it, they are officially counted among the unemployed. Though in most all markets for goods and services that achieve equilibrium there are buyers and sellers who cannot participate because prices are too high or too low, when this happens in labor markets, households are left without income and other compensation, like health insurance and retirement plans. Hence, unemployment of labor resources has direct and immediate impacts on the lives of everyone who depends on the productivity of the unemployed worker.

To be unemployed according to the measures used in most industrialized countries, a worker has to be actively seeking work. The unemployment rate measures the percentage of the labor force, which includes those employed plus the unemployed who are actively seeking work but cannot find it. Sometimes the labor force participation rate is a better measure of how intensively productive resources are used in an economy; this measures the percentage of a total population (civilians, noninstitutionalized, over the age of 16) that is either employed or unemployed but actively seeking work. These measures can be applied to subpopulations so that economists can also track unemployment and labor force participation rates by gender, location, racial and ethnic origin, age cohort, and so forth. Given the significance of employment to both individual workers and to national productivity, it is important to watch for trends and understand patterns that might be occurring and their impacts on public policy.

Note that not every member of a population is included in the labor force, and not every person who is pursuing productive activities in an economy is included in the labor force. For example, discouraged workers, defined as people who are not working and have stopped seeking work, are not part of the labor force. People who volunteer in a variety of unpaid capacities, who are working in unpaid internships, or who are engaged in unpaid household or family production, are not included as part of the labor force. Employment data provide a proxy for the extent to which an economy is using its labor resources but come nowhere near truly measuring the output of labor resources in an economy over time.

Unemployment takes a variety of forms and can be considered more or less significant depending on its type. Frictional unemployment tends to be short in duration. When workers lose jobs, it naturally takes some time and effort to seek out and select new job opportunities. Contrast this with structural unemployment, which tends to be long term and occurs because a worker’s skills no longer fit the mix of jobs available in the economy in which he or she lives or because a worker lacks the skills needed to find a job that can use them. Seasonal unemployment occurs when the demand for workers of a particular type just does not exist at particular times of the year (there are no blueberries to pick in Maine in January), while cyclical unemployment occurs because demand for labor of many types decreases when the level of economic activity declines (fewer boat salespersons are needed during a recession.)

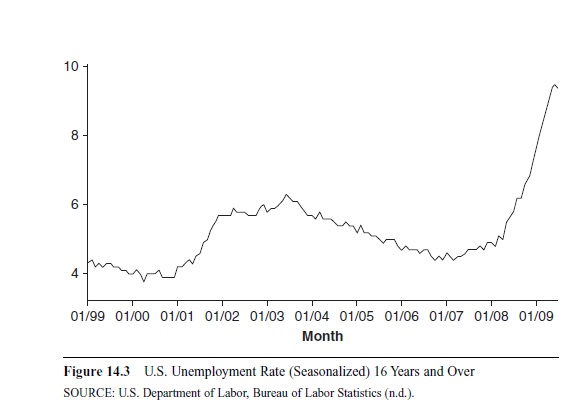

Figure 14.3 describes the path of unemployment in the United States for the 1999 to 2009 period. It is clear that recessionary pressures in late 2007 and 2008 had a tremendous impact on labor markets and on the number of jobs available to job seekers. Unemployment is referred to as a lagging indicator of the level of economic activity, which in this case means that recessionary pressures on other aspects of the economy, like demand for final goods and services or prices of other significant inputs like oil, were impacted months before firms began to lay off workers or decrease hiring. Toward the end of the recession, although other aspects of an economy might be showing marked signs of improvement, the unemployment rates might still be rising. Thus, it is very important that economists and policy makers use movements in unemployment rates with extreme care when making predictions about the health of the overall economy.

Figure 14.3 U.S. Unemployment Rate (Seasonalized) 16 Years and Over SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (n.d.).

Figure 14.3 U.S. Unemployment Rate (Seasonalized) 16 Years and Over SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (n.d.).

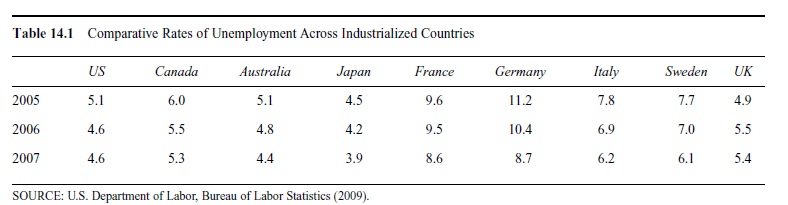

Table 14.1 describes unemployment rates for a variety of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. It is clear that industrialized countries have different experiences in their own labor markets. This is caused by a variety of factors, some political and cultural in nature and others having to do with the product mix that the country produces or with historical factors that influence production and consumption. For example, Germany’s relatively higher unemployment rates may be due to its recent incorporation of East Germany as part of its economic base or to its generous social safety net that allows the unemployed to receive a greater package of benefits. It could be due to the changes in migration regulations and expectations that have come along with expanding membership in the European Union. It could also be due to the strong manufacturing tradition in Germany that may be increasingly moving to lower-wage countries. All of these sorts of factors must be weighed when comparing unemployment rates across time and across economies.

Though unemployment is always painful for the individual experiencing it, structural unemployment is the type that causes most distress for economists. It leads to an extended lack of income for individuals and their families and can lead to serious psychological problems, including depression, that can lead to other social ills, including domestic violence and substance abuse. The severity of these problems often depends on the social safety provided by the government for the unemployed, which differs widely across countries around the world. Though most industrialized countries have some level of support for unemployed workers, the level of support, the nature of the support (pure monetary support vs. access to job training and/or education), as well as the stigma attached to accessing this support, affect the willingness and ability of workers to remain unemployed.

Policy Implications

There are many, many public policy implications of labor market decisions and outcomes, some affecting the demand side of the marketplace and some affecting the supply side. Labor markets play fundamental roles in an economy, providing inputs for production, giving people a sense of purpose and well-being, and providing income and economic resources for household consumption. Unemployed workers tend to be angry voters, so most governments around the world embrace full employment, variously defined, as an important component of political and economic stability.

Employment Policy

Should the goal of an economy be to eliminate all unemployment? Should governments and policy makers establish programs that lead to an unemployment rate equal to zero? Two questions arise here: (1) Is it possible to have no unemployment, and (2) is it desirable to have no unemployment?

Table 14.1 Comparative Rates of Unemployment Across Industrialized Countries

Table 14.1 Comparative Rates of Unemployment Across Industrialized Countries

Economists sometimes use the term natural rate of unemployment, defined as the level of unemployment that will exist in an economy at full employment. This seeming oxymoron is actually a way of describing an economy that has reached a rate of productivity that can be maintained without placing inflationary pressure on resource prices or undue stress on productive resources of all sorts. The natural rate of unemployment in the U.S. economy seemed to be around 5% through the 1990s, but then as the combination of low interest rates and war in Iraq stimulated production, it seemed as though the natural rate fell to around 4.5%. In the United States, because government policy makers and the Federal Reserve Board can both impact the level of overall economic activity, the goal is to achieve a stable level of output and employment in the long run that guides decision making and policy action.

To steer the economy toward full employment, the government can use fiscal policies that affect aggregate demand. In some cases, this means changing the level of spending on some combination of entitlement programs and discretionary spending projects. For example, in 2008, when the U.S. economy seemed headed for a deep recession, the government increased the duration of unemployment benefits, shifted resources into “shovel ready” spending projects like roads and bridges, and promoted the Cash for Clunkers program to increase household spending on new automobiles.

Other government policies directly subsidize job training for workers whose skills do not match current job offerings. This might involve grants to subsidize college students (Pell grants, for example) or more targeted initiatives designed to train workers for occupations that are expected to expand in the near future. For example, the Employment and Training Administration (ETA) administers federal government job training and worker dislocation programs, federal grants to states for public employment service programs, and unemployment insurance benefits. These services are primarily provided through state and local workforce development systems.

In response to the significant challenges presented to American workers by the recession, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Recovery Act) was signed into law by President Obama on February 17, 2009. As part of this plan, the ETA will be a key resource for the administration’s “Green Jobs” initiative. As described on the ETA Web site (www. doleta.gov),

——-The Green Jobs Act would support on-the-ground apprenticeship and job training programs to meet growing demand for green construction professionals skilled in energy efficiency and renewable energy installations. The Act envisions sound and practical energy investments for 3 million new jobs by helping companies retool and retrain workers to produce clean energy and energy efficient components or end products that will result in residential and commercial energy savings, industry revenue, and new green jobs throughout the country.

This type of public policy, directed at workforce development and training, is designed to move workers into productive sectors of the American economy, making important human capital investments that lead to viable employment as well as to a more stable economy.

Employment Taxes

Income and other employment taxes play an important role in providing incentives for workers to participate in labor markets. One of the primary methods of taxation used by governments at many levels is to directly tax income. Typically, a percentage of each dollar earned is paid as tax, and in many cases the percentage increases as total income increases, making income taxes progressive in structure. This means that workers pay increasing percentages of marginal income as tax as income increases.

Income taxes serve a variety of purposes. First, they provide money to finance government expenditures. Local, state, and federal levels of government all need revenues in order to provide services; income taxes provide that revenue in many cases. Second, income taxes can affect the behavior of workers. If income taxes are increased, workers might increase their participation in labor markets in order to make up for household income lost to tax payments. However, workers might decrease their participation in labor markets in order to take advantage of the now lower opportunity costs of spending time out of the labor markets. That is, because effective wage rates fall as income tax percentages increase, it is less expensive to spend time out of the labor market.

If income taxes are decreased, workers might increase their participation in labor markets because the opportunity cost of spending time out of the labor market has increased. Higher effective wage rates mean that it is more expensive to spend time out of the labor market. However, workers might decrease their participation in labor markets because they can earn the same level of income now with less time spent on the job.

These opposing responses to changes in income tax rates make it very difficult to determine the right mix of policy to achieve government objectives. If the goal is to encourage workers to provide more work hours, should taxes be increased or decreased? If the goal is to encourage workers to provide fewer work hours, should taxes be increased or decreased? Policy has to be very carefully determined, based on the average levels of income earned in a particular market or the historical response of workers to tax changes in the past. For example, typically low-wage workers respond to increases in tax rates by working more hours. If the goal of policy is to encourage workers with jobs to provide a greater number of hours, it is smart to increase income tax rates. On the other hand, if the goal is to encourage labor force participation among discouraged workers, the appropriate policy is to increase the effective wage by lowering tax rates. This means that the opportunity costs of remaining unemployed have increased and it is now more expensive to stay out of the labor force.

Minimum Wages

In some instances, government policy makers intervene in markets for a variety of goods and services by setting legal minimum prices. These price floors, set to protect sellers of a good or service, provide sellers with higher levels of income than they would receive if the market equilibrium were allowed to allocate resources. Price floors are used in a variety of markets for goods and services in the United States, particularly in markets for agricultural products like cheese, milk, and sugar.

Minimum wages are used in labor markets for the same reasons. Legal minimum wages provide low-wage workers with protection from wages that may be low because of large supplies of workers who enter these markets. Particularly in urban areas or areas near borders, where large numbers of immigrant workers tend to settle, minimum wages help to alleviate poverty among the nation’s most vulnerable populations.

In the United States, the federal government established mandatory minimum wages through the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. In the midst of the Great Depression, this policy was designed to provide minimal levels of income for workers who were trying to make their way back into labor markets after extended spells of unemployment. In 2009, the federal minimum wage was increased from $6.55 per hour to $7.25 per hour. Some states, particularly those with very high costs of living, like Connecticut, set their minimum wages higher than what is federally required. Though federal lawmakers have increased the wage several times in recent years, the federal minimum is not indexed to inflation or to increases in labor productivity, and so workers have no guarantee that they will maintain purchasing power over time or that their compensation will rise as their own productivity increases.

Increases in the minimum wage have become quite controversial in most of the countries or markets in which they are imposed. Some argue that establishing wage floors causes higher levels of unemployment in affected markets. For example, some people argue that in the market for people who wash dishes in New York City, if firms are required to pay higher wages, they will move up their demand curves and hire fewer worker hours. Others argue that though this might be true, the demand for dishwashers in New York City is highly inelastic; this means that when wages rise, quantity demanded falls, but by a relatively small amount. So the question becomes an empirical one: When wages rise in low-wage labor markets, how significant is the decrease in quantity of labor demanded? If this decrease is small, then the income gains to workers who remain employed create greater benefits, even though some workers are forced out of the labor market. Many studies have been conducted to measure this impact, particularly on teenage workers, who are the most common recipients of the minimum wage. Though results are mixed, most conclude that the negative impact of increases in the minimum wage on employment in affected markets is small or nonexistent.

A more extreme form of the minimum wage that is gaining momentum is the living wage. This is defined as a minimum amount of money required by a worker to maintain his or her own living within a particular market. The Universal Living Wage Campaign is based on the premise that anyone working 40 hours per week should be able to afford basic housing in the market in which that labor is exchanged; this obviously requires higher hourly wage rates far in excess of the federal minimum wage. For example, the living wage in 2002 was $10.86 in New Haven, Connecticut, and $10.25 in Boston, Massachusetts. Even at these higher levels, the price elasticity of demand for labor in low-wage markets is quite inelastic, indicating that increasing wages to even this level will not result in significant increases in unemployment.

Future Directions

Labor markets are complex and dynamic, and so the possibilities for future directions are endless. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects significant changes in the labor force in the coming years, as follows. Fewer younger workers will be available to enter the labor force, and most of the growth in the supply of labor will come from new immigrants to the American economy. On the demand side, manufacturing jobs will continue to move overseas, while job growth in the green economy and service sector will continue to increase (Toossi, 2007). Combined with these demographic and sector shifts, several other factors will help to determine the nature of labor markets in the coming decade.

Technology

As technology provides greater opportunities to enhance worker productivity, it also provides applications that replace worker effort with machines, computers, and robots. This tension between labor and capital as substitutes in production (capital equipment and technology replacing humans in production processes) and as complements in production (capital equipment and technology increasing the productivity of humans in production processes) will not be resolved easily and will need to be considered on a case by case basis across the economy as new technology changes the nature of the work that people do.

Immigration Policy

As noted above, immigrants are almost certain to account for a significant portion of the growth in the labor force in the next decade. Immigrants enter the United States seeking higher income and living standards than they have experienced in their home countries. Given the inequality in the distribution of income and wealth around the globe, as long as immigrants can gain access to the American marketplace, the investment in migration is more than worth the costs in terms of personal and family dislocation and downward job mobility.

The key to predicting the impact of this immigration is the degree to which U.S. citizens are able to provide welcoming communities for workers from other countries. Though a variety of laws and regulations limit the ability of firms and communities to discriminate against workers they do not want to accept, equal treatment and opportunity is not the norm in many regions of the country. This means that social networks among immigrant populations become more and more important, and the ability of immigrants to gain access to skills, attitudes, and workplace norms will be crucial if labor productivity is to continue growing as new migrants are absorbed into American life.

The burden of accommodating large immigrant populations can be quite overwhelming to a community. Particularly if border communities like Miami, Los Angeles, and Houston are considered, increases in immigration (both legal and illegal) strain public services like hospitals and schools. Even when people in a community want to welcome productive workers into their midst, they may find it difficult to provide for them in ways that are equitable.

Labor Unions

The union movement in the United States has declined steadily during the past five decades, with membership down to around 12% of the labor force from around 30% in the late 1950s. There are many reasons for this decline, some economic and some political. The primary sectors of the economy that led the union movement have declined in importance in recent years, led by autoworkers, mine workers, and garment workers. All of these industries have seen increasing competition from international producers and have subsequently been unable to compete with firms in the global economy that have gained a variety of efficiencies in production and employment.

Further, changes in the political climate have made it increasingly more difficult for unions to organize workers. On August 3, 1981, more than 12,000 members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) went on strike and were subsequently fired by President Ronald Reagan, who determined that the strike was illegal. This decision, in one instant, shifted the balance of power between firms and unions significantly in the direction of employers. From that time, policy and decisions by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) began to work in favor of the employer and more often against the ability of workers to form collective bargaining arrangements with their employers. Note that the labor movement in other countries, particularly in Europe, remains strong, with around half of all workers unionized in Great Britain, Germany, Austria, and Italy.

Finally, as the manufacturing sector of the economy has shrunk, the service sector has grown tremendously, representing nearly 80% of business activity in the United States today. Service employees have historically been difficult to organize because they are often female dominated (women are more difficult to organize) and often dispersed across a wide variety of work settings (small offices, working from remote locations, etc.). Unless employees in service industries find ways to unionize more effectively, the union movement will continue to lose relevance in the American economy.

Conclusion

In a perfect world, labor markets allocate human effort in production toward its most productive use. This research paper has endeavored to explain that allocation process by exploring the behavior of buyers and sellers in markets for human resources and then introduced the role of government policy makers in altering these market-determined outcomes.

The key to understanding the nuances of labor market behavior is in remembering that work is a fundamental source of human dignity. Though economists often focus on labor as a productive resource, which it of course is, there are aspects of the relationship between employer and employee that are clearly emotional, value laden, and culturally determined. This leads to a level of complexity in resource allocation that we do not see with other productive inputs like computers, robotics, or acres of land. However, it is this complexity that provides us as economists with rich avenues for intellectual investigation and policy analysis.

Bibliography:

- American Association of University Professors. (2006, March-April). Annual report of the status of the profession, 2005-2006. Academe. Available at https://www.aaup.org/reports-publications/2005-06salarysurvey

- Becker, G. S. (1965). A theory of the allocation of time. Economic Journal, 75(299), 493-517.

- Becker, G. S. (1971). The economics of discrimination (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bergman, B. (1986). The economic emergence of women. New York: Basic Books.

- Blau, F. (1984). Discrimination against women: Theory and evidence. In W. A. Darity, Jr. (Ed.), Labor economics: Modern views (pp. 53-89). Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff.

- Borjas, G. J. (1987). Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants. American Economic Review, 77, 531-553.

- Freeman, R. B., & Medoff, J. L. (1984). What do unions do? New York: Basic Books.

- Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (1998). The origins of technology-skill complementarity. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113, 693-732.

- Heckman, J. J. (1974). Life cycle consumption and labor supply: An explanation of the relationship between income and consumption over the life cycle. American Economic Review, 64, 188-194.

- International Labour Office. (2003). Yearbook of labour statistics. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

- Katz, L. F., & Murphy, K. M. (1999). Changes in the wage structure and earnings inequality. In O. C. Ashenfelter & D. Card (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (pp. 1463-1555). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Lazear, E. P. (2000). Performance pay and productivity. American Economic Review, 90, 1346-1361.

- Mincer, J. (1962). Labor force participation of married women. In H. G. Lewis (Ed.), Aspects of labor economics (Universities National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Studies No. 14, pp. 63-97). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mincer, J. (1976). Unemployment effects of minimum wages. Journal of Political Economy, 84, 87-104.

- Nelson, J. (1993). Beyond economic man: Feminist theory and economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rosen, S. (1986). The theory of equalizing differences. In O. Ashenfelter & R. Layard (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (pp. 641-692). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Spence, A. M. (1973). Job market signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87, 355-374.

- Toossi, M. (2007). Labor force projections to 2016: More workers in their golden years. In Monthly Labor Review. Available at https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2007/11/art3full.pdf

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau. (1975). Historical statistics of the United States, colonial times to 1970 (Bicentennial Ed., Vol. 1, pp. 131-132). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Labor force statistics from the current population survey. Available at https://www.bls.gov/cps/lfcharacteristics.htm

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2007). National compensation survey: Occupational wages in the United States, 2006 (table 2). Available at https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ncswage2006.htm

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2008-2009a). Physicians and surgeons. In Occupational outlook handbook. Available at https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physicians-and-surgeons.htm

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2008-2009b). Registered nurses. In Occupational outlook handbook. Available at https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/registered-nurses.htm

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2009). International comparisons of annual labor force statistics, adjusted to U.S. concepts, 10 countries, 1970-2008 (table 1-2). Available at https://www.bls.gov/fls/notes.htm

- Webster, T. (1999). Work related injuries, illnesses, and fatalities in manufacturing and construction. In Compensation and working conditions. Available at https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/cwc/work-related-injuries-illnesses-and-fatalities-in-manufacturing-and-construction.pdf

- Viscusi, W. K. (1993). The value of risks to life and health. Journal of Economic Literature, 31, 1912-1946.