Sample Dispute Resolution In Economics Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Negotiation is common in many settings. A common feature of all negotiation is an understanding by the parties to the negotiation about the process that will be used to resolve a dispute in the event that the parties fail to reach agreement. Disputes between labor unions and employers can end in a strike, or can be resolved by arbitration. Disagreement over contracts or tort damages can result in civil litigation and a decision by a judge or jury. Disagreement between nations can result in military disputes. The dispute settlement process defines the expectations that the parties have about what will happen in the event that no agreement is reached. And this process, in turn, determines negotiator behavior.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

There are two fundamental types of dispute settlement mechanism. The first is the systematic imposition of costs on each side. Strikes and military disputes are examples of this type of mechanism. No determinate end to the dispute is implied, but presumably one or both parties concedes sufficiently to make an agreement possible and end the dispute. The second mechanism is the mandating of a settlement by a third party. Arbitration of labor and commercial disputes, and litigation of civil disputes, are examples of this type of mechanism.

Both types of mechanism (strikes and arbitration) are used in the resolution of labor disputes, and the discussion here focuses on that area. This discussion is necessarily selective and is meant to provide a brief introduction to important concepts and issues. See Hirsch and Addison (1986) for a more extensive survey.

1. Strikes

A difficult problem in the economics of labor unions is the modeling of strikes. The difficulty arises because strikes appear to be non-equilibrium phenomena. Both sides would have been better off if they had been able to agree on whatever the outcome was without bearing the costs of a strike. In other words, strikes are Pareto-dominated by the same bargaining outcome without a strike. While research on strikes in the United States has diminished with the level of strike activity in the USA since the mid-1980s, there was an active empirical literature in the 1970s and 1980s.

Ashenfelter and Johnson (1969) developed a nonequilibrium model of strike activity by attributing to the union an arbitrary concession schedule positing an inverse relationship between the minimum acceptable wage and the length of strike. The firm selects the point on this schedule that maximizes profits, the tradeoff being longer strikes involving larger up-front strike losses, but lower labor costs into the future. Ashenfelter and Johnson used this model to motivate an empirical analysis of the aggregate level of strike activity in the United States. Farber (1978) used the same theoretical framework to estimate a structural model of the joint determination of wage changes and strike length using data on the outcomes of a time-series of cross-sections of negotiations for large US corporations.

Tracy (1986) developed an equilibrium model of strikes based on learning in a model of asymmetric information (Fudenberg and Tirole 1981, Sobel and Takahashi 1983). The model is based on the idea that the union does not know the profitability of the firm. The union would like to extract a high wage from high-profit firms and a lower wage from low-profit firms. The key is that high-profit firms have a high cost of bearing strikes relative to low-profit firms. In this case, the union can make a high initial wage demand. High-profit firms will prefer to pay this wage immediately rather than to lose profits during a strike. Low-profit firms will prefer to lose their lower profits during the strike in exchange for a lower wage into the future.

Tracy (1986) used this model to generate the empirical implication that there will be more strikes where there is more uncertainty about the firm’s profitability. He then implemented this model using data on a large number of negotiations and using the volatility of daily stock returns as his measure of uncertainty about profitability. He finds evidence that uncertainty is correlated positively with strike activity.

A final point is that the declining concession schedule in the Ashenfelter–Johnson model can be interpreted as a reduced-form expression of the union learning function. As the strike goes on, the union is willing to accept a lower wage as they learn that the firm is lower-profit.

It is quite possible that strikes are not equilibrium phenomena, and that the insistence in the economics literature, both theoretical and empirical, on equilibrium explanations, is inappropriate. Strikes can result from miscalculation. In particular, the parties may be relatively optimistic about the outcome after a strike. For example, the union may expect a wage settlement of $20 hour after a strike, while the firm expects to pay only $18 hour after the same strike. If the cost of a strike is $0.50 hour to each side, then the union will accept no less than $19.50 to avert the strike, while the firm will be willing to offer no more than $18.50. The result will be a strike. Of course, the expectations of both sides cannot be accurate, ex post. This relative optimism can have a variety of sources. One possibility with a long history in the industrial relations literature, is that the parties selectively overweight arguments that are favorable to their side (Walton and McKersie 1965, Neale and Bazerman 1991). However, relative optimism can be generated even with appropriate weighting of available information. If each side is getting independent (and accurate in expectation) information on the likely uncertain outcome, for some fraction of the time the information will lead to relatively optimistic expectations sufficient to outweigh the costs of a strike. Strikes will occur in these cases.

2. Arbitration

In the United States, arbitration is used commonly to determine the terms of labor contracts in the public sector in cases where the parties cannot agree on their own. In conventional arbitration, the arbitrators are free to impose whatever settlements they deem appropriate. A common alternative is final-offer arbitration, where the arbitrator must select one of the final offers submitted by the parties and cannot compromise.

2.1 Conventional Arbitration

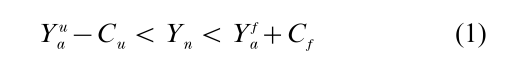

Consider the following simple model of the negotiation process where conventional arbitration is the dispute settlement mechanism (Farber and Katz 1979). Suppose the parties are negotiating over the split of a pie of size one. The share of the pie going to the union is Y, and the share going to the firm is (1-Y). The arbitrator will impose a settlement of Ya, and each party has a prior distribution on Ya. Let Yua and Yfa represent the prior expected value to the union and firm, respectively, of the arbitration award. Finally, let Cu and Cf represent the cost to the union and the firm of using arbitration (denominated in pie shares). Assume further that the parties are risk neutral, so that the union will prefer any negotiated share for itself (Yn) such that Yn > Yua -Cu and the firm will prefer any negotiated share for itself such that 1-Yn >1-Yua– Cf . These are the reservation values of the parties in negotiation. The result is a contract zone of settlements preferred by both sides to arbitration that consists of all shares that fall in the range:

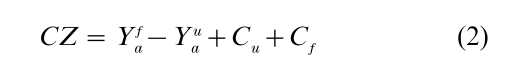

The size of the contract zone is:

In the simplest model, there will be a negotiated settlement whenever CZ≥0, and there will be an arbitrated outcome whenever CZ<0.

This model provides an important insight into when one might expect a dispute. Relative optimism about the likely arbitration award (Yua >Yfa) can be a reason for a dispute. If the relative optimism is sufficiently great to outweigh the total costs of arbitration (Cu +Cf), then there will be no contract zone, and arbitration will be required. Thus, relative optimism is a cause of disputes. Clearly, higher total costs of arbitration imply a larger contract zone. Larger costs make it less likely that any degree of relative optimism will cause there to be no contract zone. Thus, larger total costs of disputing reduce the likelihood of disputes. This latter property is implied by any reasonable model of disputes.

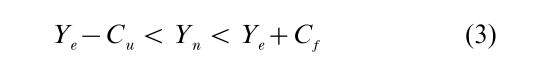

The model also demonstrates how the dispute settlement mechanism determines fundamentally negotiated outcomes. Consider the case where the parties have identical expectations about the arbitration award of Ye=Yua=Yfa. The size of the contract zone in this case is determined entirely by the costs of arbitration (Eqn. 2), and there will be no dispute. The negotiated settlement will lie in the range defined by:

In other words, the negotiated settlement will lie in some range around the common expectation of the arbitration award.

One criticism of conventional arbitration as a dispute settlement mechanism in labor disputes is that arbitrators appear to split the difference between the demands of the parties, resulting in an arbitration award that is close to the average of the demands. However, Eqn. 3 makes it clear that the opposite is likely to be true: The negotiated settlement is likely to lie between the reservation values of the parties. Mnookin and Kornhauser (1979) and Farber (1981) present analyses that make this point.

2.2 Final-Offer Arbitration

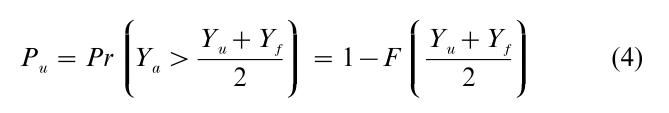

The perception that arbitrators split the difference in conventional arbitration led to the belief that conventional arbitration ‘chilled’ bargaining by providing the parties with an incentive to maintain extreme demands. This led to the development of final-offer arbitration, which prevented the arbitrator from compromising (Stevens, 1966). Farber (1980) developed a simple model of final-offer arbitration where arbitrators select the offer closest to what they would have imposed in conventional arbitration (Ya). In this model, the probability that the union’s offer is selected is:

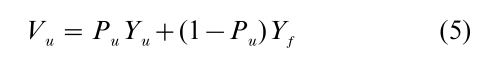

where Yu and Yf represent the final offers of the union and the firm respectively and F (·) represents the cumulative distribution function of the parties’ common prior on Ya.

Assuming risk-neutrality, the expected payoff to the union from final-offer arbitration is:

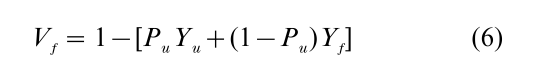

and the expected payoff to the firm is:

The Nash equilibrium final offers of the parties are the offers such that (a) Yu maximizes Vu conditional on Yf, and (b) Yf maximizes Vf conditional on Yu. These offers have the property that neither party will desire to change its offer.

Since the parties are uncertain about Ya, the Nash equilibrium final offers reflect a tradeoff between the value to the party of its offer if its offer is selected, and the probability that its offer is selected. A more extreme offer yields a higher payoff to the party if its offer is selected by the arbitrator, but it lowers the probability that the offer will be selected.

A key implication of this model is that final offer arbitration may not encourage more convergence in negotiation than conventional arbitration because of the desire to present optimal final offers to the arbitrator that may be extreme.

2.3 Empirical Evidence

Ashenfelter and Bloom (1984) present evidence from arbitration of contract disputes for public sector employees in New Jersey, where both conventional and final-offer arbitration are used, consistent with the general model of arbitrator behavior outlined here. They find that arbitrators use a common underlying notion of Ya to make awards in both conventional and final-offer arbitration. Their evidence is consistent with the arbitrators’ decision in final-offer arbitration being to select the offer closest to Ya. Bazerman and Farber (1986) reach similar conclusions based on evidence from arbitration awards, both conventional and final-offer, made by professional arbitrators in hypothetical cases.

Convincing evidence is scarce on whether final-offer arbitration leads to more settlements and reduces reliance on arbitration. Ashenfelter et al. (1992) present experimental evidence that does not show higher rates of agreement in final-offer arbitration than in conventional arbitration.

Bibliography:

- Ashenfelter O, Bloom D E 1984 Models of arbitrator behavior. American Economic Review 74: 111–24

- Ashenfelter O, Currie J, Farber H S, Spiegel M 1992 An experimental comparison of dispute rates in alternative arbitration systems. Econometrica 60: 1407–33

- Ashenfelter O, Johnson G 1969 Trade unions, bargaining theory, and industrial strike activity. American Economic Review 59: 35–94

- Bazerman M H, Farber H S 1986 The general basis of arbitrator behavior: An empirical analysis of conventional and finaloffer arbitration. Econometrica 54: 1503–28

- Farber H S 1978 Bargaining theory, wage outcomes, and the occurrence of strikes: An econometric analysis. American Economic Review 68: 262–71

- Farber H S 1980 An analysis of final-offer arbitration. Journal of Conflict Resolution 24: 683–705

- Faber H S 1981 Splitting-the-difference in interest arbitration. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 34: 70–7

- Farber H S, Katz H C 1979 Interest arbitration, outcomes, and the incentive to bargain. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 32: 55–63

- Fudenberg D, Tirole J 1981 Sequential bargaining with incomplete information. Review of Economic Studies 50: 221–48

- Hirsch B T, Addison J T 1986 The Economic Analysis of Unions: New Approaches and Evidence. Allen & Unwin, Boston, MA

- Mnookin R, Kornhauser L 1979 Bargaining in the shadow of the law—the case of divorce. Yale Law Journal 88: 950–97

- Neale M A, Bazerman M H 1991 Cognition and Rationality in Negotiation. The Free Press, New York

- Sobel J, Takahashi I 1983 A multi-stage model of bargaining. Review of Economic Studies 50: 411–26

- Stevens C M 1966 Is compulsory arbitration compatible with bargaining? Industrial Relations 5: 38–52

- Tracy J S 1986 An investigation into the determinants of US strike activity. American Economic Review 76: 423–36

- Walton R E, McKersie R B 1965 A Behavioral Theory of Labor Negotiations: An Analysis of a Social Interaction System. McGraw-Hill, New York