Sample Economics Of Development Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

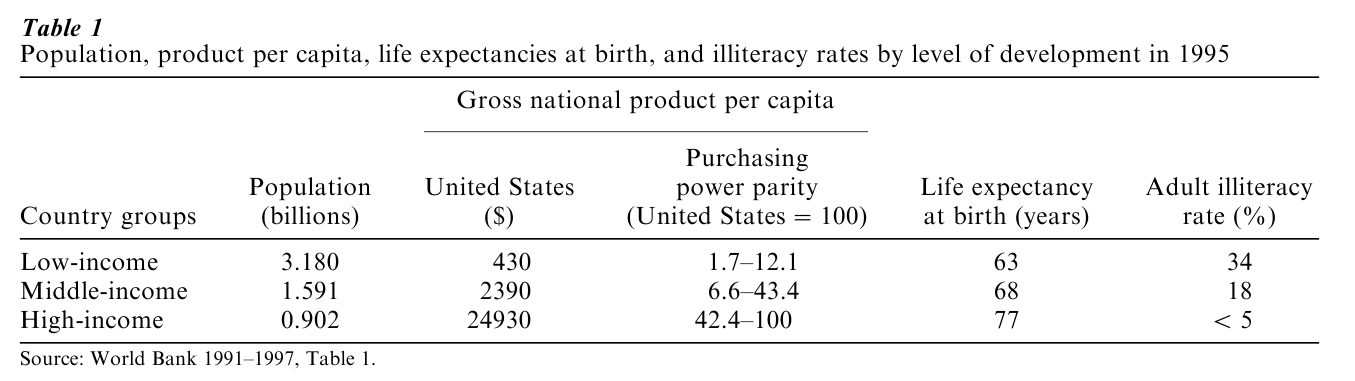

Economic development is the process through which economies are transformed from ones in which most people have very limited resources and choices to ones in which they have much greater resources and choices. Economic development therefore covers almost all areas of economics, though with modifications to reflect the particular situations of developing countries. Development economics refers to studies of economies with relatively low per capita resources: low-and middle-income economies in Table 1. About 85 percent of humanity currently lives in these economies. Product per capita in low-income economies averages 1.7 percent and in middle-income economies 9.6 percent of averages in high-income economies, with that in Switzerland over 500 times that in Mozambique. Correcting these comparisons for different price structures reduces the variations a lot, but the range still is considerable, with per capita product almost 60 times as high in the United States as in Ethiopia. Human resource indicators (e.g., life expectancies and illiteracy) also are poorer for developing than developed economies, but current differences are much smaller proportionately than are those in product per capita. The question of what causes economies to move from per capita resource levels as in Mozambique and Ethiopia to those as in Switzerland and the United States is the fundamental question that development economics addresses.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Conceptualization Of Development In The Mid Twentieth Century

Prior to the neoclassical developments in economic analysis of the late nineteenth century, most influential economists, for example, Smith, Ricardo, Marx, were concerned substantially with economic development. In the decades prior to the Second World War, in contrast, most neoclassical economists were not concerned with development, but with topics such as behaviors of firms and households, general equilibrium, and efficiency and, starting in the 1930s, shortrun macroeconomic equilibria with aggregate demand shortfalls.

In the immediate post-WWII era, mainstream economics continued to focus on the extension of the neoclassical paradigm and on Keynesian macro shortrun disequilibria with virtually no attention to development. Development economics as a subdiscipline branched off from what Samuelson called the ‘neoclassical synthesis’ of mainstream economics because the development of poorer lands was viewed by development economists as different in essence from concerns that dominated the neoclassical synthesis. Development was seen as involving discontinuous shifts from a stagnant low-income traditional equilibrium (‘a low level equilibrium trap’ or a ‘vicious circle of poverty’) to a modern higher-income, changing, and growing economy with increasing average per capita income, poverty alleviation and improvements in human resources. Development was viewed as requiring structural change different in kind from the marginalism of neoclassical economics.

The dominant paradigm of the new reborn discipline of development economics in the mid-twentieth century was based on key perceptions about the way markets, incentives, and other institutions operated in poor countries. These, in turn, had important policy implications.

1.1 Key Perceptions About Markets, Incentives, And Other Institutions In View Of Development In The Mid-Twentieth Century

1.1.1 Surplus Labor And Capital Shortages. Factor proportions in poor countries implied high labor to capital ratios. Family farms firms with sharing rules based on average products permitted marginal labor products to fall to zero so that labor was in surplus in large traditional agriculture sectors. Surplus labor presented an advantage because, if it could be moved to industry, large gains in product could be obtained and much of the income generated could be reinvested in further capital accumulation since the ‘unlimited supply of labor’ keeps real wages low. Physical capital was relatively scarce, so that, in Nurske’s (1952, pp. 1–2) words, ‘the problem of development is largely … a problem of capital accumulation.’ But domestic capital accumulation was limited by a vicious circle: low incomes meant low savings so that investment was low that kept incomes low. Human capital was given little emphasis.

1.1.2 Limited Role Of Domestic Markets. Markets had limited efficacy because: (a) large population shares, including traditional peasants and governmental officials, were not responsive to market and other incentives. (b) Markets were not well developed because of large subsistence sectors, costly transportation and communication, and the predominance of mechanisms internal to households and firms for transferring resources across time and space. (c) Markets did not incorporate well information about demand complementarities of investments (e.g., Rosenstein Rodan 1943) and could not provide the right guidance for investments that would change the basic structure of the economy with more than marginal effects. (d) There were important market failures of the types considered in mainstream economic analyses: technological externalities not transferred through markets (e.g., pollution), increasing returns to scale relative to market sizes, and ‘public goods’ the use of which are not ‘rival’ so that more consumption by one individual does not mean that less is available for another entity (e.g., information). (e) Some major actors in markets—rural moneylenders, landlords, and traders—were ‘rapacious profiteers’ who ‘exploited’ the uninformed poor by paying them low product prices and charging them high input and credit prices.

1.1.3 Key Role Of Industrialization. Agriculture dominated employment and production. But the development process was in substantial part industrialization. Productivity-enhancing technologies and positive externalities were primarily available for industry, domestic demand would shift towards industry with increased incomes because of income inelastic demands for food (Engel’s law), surplus labor in agriculture could be shifted to productive uses in industry, savings potentials were much greater in industry, and industrialization was essential for maintaining national autonomy (e.g., Mandelbaum 1945, Rosenstein-Rodan 1943, Singer 1950, Mahalanobis 1955, Lewis 1954, Ranis and Fei 1961).

1.1.4 Limited Prospects In International Markets. Pessimism prevailed regarding international market prospects, in part because of the market collapses in the 1930s. Prebisch (1950) and Singer (1950) argued that international trade transferred most benefits from increased productivity in poor countries to richer countries, the terms of trade of primary producers decline secularly because demands were income-inelastic for primary commodities and the developed countries had monopoly power in markets for manufactured products, and opportunities for developing countries to expand their manufacturing exports were limited because such markets would not grow quickly and these markets were dominated by monopolistic producers in the high-income countries who had succeeded in establishing protectionist policy-determined barriers to expanded manufacturing imports from developing countries. International capital markets would not provide sufficient investable funds for development and they cause exploitation and crowd out domestic investments.

1.1.5 Policy Makers Ha E Good Information, Are Disinterested And Are Effective. Policy makers could identify current and future magnitudes of negative and positive externalities, complementarities among production sectors, and responses of various entities to policies so they could and would design and implement good policies.

1.2 Policy Implications Of The View Of Development In The Mid-Twentieth Century

1.2.1 Capital Accumulation. Physical capital accumulation was central, as codified by the Harrod–Domar

dynamic equilibrium condition, which in the simplest case is that the rate of growth equals the average saving rate divided by the incremental capital output ratio (ICOR). This relation was used to calculate savings requirements to achieve growth targets given ICORs and to justify efforts to increase savings, including shifting resources from private entities to governments under the assumption that governmental savings rates exceeded private ones, and to obtain foreign savings to supplement domestic savings. When exchange rates became overvalued, foreign capital to purchase critical machinery and equipment became of particular concern, as systematized in the ‘two-gap’ model of Chenery and Bruno (1962) in which the constraint on growth is either savings or foreign exchange. Human capital accumulation was not central in most analysis partly because of the widespread perception of surplus labor.

1.2.2 Import-Substituting Industrialization With Balanced Growth. One major mechanism widely used to shift resources to industry, to protect new domestic industries against foreign competitors, and to increase economic independence was high protection, through tariffs and quotas, on manufacturing imports. This established inducements for ‘balanced industrial growth,’ with important complementarities for intermediate inputs and for final product demands (‘backward and forward linkages’).

1.2.3 Policy Mix—Quantitative, Direct Public-Sector Production, Planning, And Irrelevance Of Macro Balance. The state role was very extensive. The dominant policy mode was dirigiste. Efforts to improve markets or to use ‘market-friendly’ taxes subsidies were relatively rare. Direct quantitative regulations and allocations, including substantial investment in public-sector production, were common because it was thought that the desired ends could be effected with most certainty through such direct actions by knowledgeable, disinterested policy-makers. Publicsector investments included physical capital and human resource infrastructure and many other subsectors in the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy so that the state could control directly development. Planning often was viewed as essential because of market limitations, reinforced by international aid agencies that interpreted plans as essential evidence concerning the seriousness of countries’ development efforts. Planning agencies were concerned with investment criteria and choice of techniques for deciding on direct public sector investments and for guiding private investments. ‘Shadow’ (‘scarcity’) prices were used to evaluate social cost-benefit ratios or internal rates of return to alternative investments, with un- skilled labor valued at zero because of surplus labor and foreign exchange valued more highly than official overvalued exchange rates. A considerable literature developed methods for calculating general-equilibrium shadow prices. Multisector planning models were developed and widely used to determine sectoral primary factor requirements, physical capital investments, import substitution possibilities and ‘noncompetitive imports’ (for which domestic substitutes were not available) for target growth rates. These models generally assumed no substitution among production inputs nor among demands, focused on physical capital, and were quite aggregated with little or no variation in qualities of products. They addressed directly possibilities of supply or demand complementarities. Optimizing versions yielded shadow prices that indicated impacts on objective functions of marginal changes in binding model constraints. Often these shadow prices were not very robust to small changes in the model. Moreover, these models did not incorporate most macroeconomic phenomena, so they did not provide guidance concerning such matters as inflation. Furthermore, most of these planning models ignored or only crudely incorporated most of the major phenomena other than the supply and demand complementarities that underlay the critique of the dependence on markets (Sect. 1.1). Subsequent models improved in some important respects, for example, discontinuities were incorporated into integer programming models and price responses in Johansen-type models (1960) that led to more recent computable general equilibrium (CGE) models (Blitzer et al. 1974). But still many of the limitations noted remained.

Policies to establish macroeconomic balance—a major topic in high-income economies—were rejected as irrelevant. Rao (1952) and others argued that the separation between savings and investment that was critical in Keynesian underemployment analysis was not relevant for developing countries given the dominance of family firms. The Latin American ‘structuralists’ argued that rigidities precluded economic entities from responding quickly to changes so that orthodox currency devaluation or monetary and fiscal policies would reduce output and employment.

2. The Dominant Paradigm Concerning Development At The Start Of The Twenty-first Century

Aggregate development experience since WWII in many respects has been very impressive, though with considerable variations across economies. Average growth rates in GDP per capita have been high by historic standards and high for developing relative to developed economies. Other indicators of human welfare, such as life expectancy and schooling, have improved even more impressively. Prima facie, such success might be interpreted to ratify the post-WWII development paradigm and associated policies (Sect. 1). But the appropriate comparison should be with what could have been achieved given the conditions of the post-WWII era and appropriate development strategies and policies.

One major change in the last three decades or so of the twentieth century was the rapid expansion of systematic quantitative analyses of development, often based on data and approaches that were not available earlier. Many studies explored the underlying assumptions for the dominant initial post-WWII conceptualization of development. Some were undertaken in relatively visible large-scale comparative projects (e.g., Little et al. 1970, Bhagwati 1978, Krueger 1978, 1983, Taylor 1988, Page et al. 1993). Others have been individual country and microstudies that have investigated more detailed aspects of the development experience using new micro data sets with systematic models (e.g., see references in Chenery and Srinivasan 1988–1989 and Behrman and Srinivasan 1995; some more recent examples are Behrman et al. 1997, 1999, Foster and Rosenzweig 1995, 1996a, 1996b, Jacoby 1995, Jacoby and Skoufias 1997, Pitt and Khandker 1998).

These studies question many of the assumed initial conditions in the post-WWII development paradigm and suggest more nuanced characterizations of others. They suggest: (a) traditional agriculture is relatively efficient and traditional institutions such as share- cropping, contracts tied to multiple transactions, attached farm servants, arranged marriages, and migratory patterns are efficient arrangements given imperfect or absent capital and insurance markets. (b) Substantial increases in savings and physical capital investments rates are not sufficient for development because (i) incentives structures affect strongly on- going productivity growth and (ii) human resource development related to nowledge acquisition and adaptation is critical. (c) Domestic markets work well for many goods and services and returns to market improvements through infrastructure development, better information, and lessening policy barriers to well-functioning markets are often great. Nevertheless some markets—particularly those related to capital, insurance, and information—are imperfect or missing. (d) Industrialization is not equivalent to development and industrialization strategies that penalize other production sectors may retard development. (e) International markets have presented substantial opportunities for developing countries, with the most successful experiences being for those developing economies (initially primarily in East and Southeast Asia) that expanded rapidly their exports and used international markets to induce ongoing productivity improvements as well as sources of foreign investment. (f) Policymakers have limited information and may be rent-seekers rather than knowledgeable and disinterested.

This re-evaluation of initial conditions has substantial implications for policies. Because of the combination of currently perceived much greater responsiveness, limited information (and information asymmetries) faced by governments, limited governmental implementation capacities, much greater variations in quality of goods and services, much more efficient transmission of certain types of information through unhindered markets, important role of markets in inducing greater efficiency, much greater importance of basic macroeconomic stability, and rapid changes in markets and in technology than assumed in the immediate post-WWII paradigm, there has been a sea change in perceptions of appropriate governmental roles and of the best mix policy mix. A broad new consensus had risen by the early 1990s on the nature of development processes and implications for policies. Components of this consensus include the following.

2.1.1 The Basic Economic Environment Must Be Conducive For Investments. The two major components are: (a) a stable macroeconomic environment with noninflationary monetary policy, fiscal restraint, and international balance (e.g., World Bank 1991, Corbo et al. 1992, Page et al. 1993) and (b) institutions that permit investors to have reasonable expectations of reaping much of the gains from their investments. Domestic macrobalance is important because inflationary taxes advocated by many earlier development economists are inefficient, inequitable, erode confidence in policy and in the prospects for the economy, discourage longer-run productive investments by increasing uncertainty, and are difficult to eliminate. Balance in international economic interchange is important so that critical imports of intermediate and capital goods can be maintained, pressures for increased efficiencies are ongoing through exposure to world markets, and access to international finance and technology is maintained. Institutions include basic property rights, legislative and legal systems that resolve disputes fairly, and various mechanisms to share (but not to eliminate) risks.

2.1.2 Human Capital Is Important, Additional To Physical Capital. In the views of some, investment in human resources is in itself development. For most mainstream development economists, in addition to any direct welfare effects of better human resources, there are important productivity effects. Positive externalities through human resource investments may be considerable, moreover, primarily because of externalities to knowledge and to capacities for individuals to find and to process information. Given gender roles and current market policy failures, the social returns to human capital often may be relatively high for investments in females (King and Mason 2000).

2.1.3 Responsiveness To Incentives Created By Markets And Policies Are Broad And Often Substantial. Therefore, it is desirable that markets and policies create incentives for behaviors that are socially desirable and not sufficient, as in the earlier paradigm, that policy makers know shadow prices. Economic entities also adjust many or even all elements of their behaviors in response to changes. Therefore, anticipating full effects of policies or market outcomes on behavior is difficult because of such cross-effects. The impact of new technological options, for example, may increase the value of educated women in marriage markets if gender roles dictate that women play major roles in child education (Behrman et al. 1999).

2.1.4 Information Problems Are Pervasive In A Rapidly Changing World So Incentive-Compatible Institutions And Mechanisms Are Desirable. Information is imperfect in general, information that policy makers implementers have often is less and more dated than the information that individuals have who are directly involved in production and consumption of particular goods and services, asymmetrical information creates incentives for opportunistic individual behaviors that are likely to be socially inefficient and inequitable, and markets are relatively efficient in conveying certain types of information. Rather than attempting directly to regulate and monitor many micro activities related to the development process, governments more effectively can support institutions that are relatively effective in inducing desirable behavior. The oft-cited claim that an important aspect of the successful East Asian development experience has been outward orientation, for example, may be viewed in part as a mechanism for encouraging increasing productivity through forcing competition on world markets. Likewise, efforts to make markets work better through open and transparent bidding for governmental contracts, better market integration to lessen monopoly power, introducing voucher systems and decentralization of human resource-related services, eliminating governmental regulations on entry, improving communication and transportation and subsidizing or mandating information that has public goods characteristics all may have important effects in increasing efficiency.

2.1.5 Selective Global And Directed Policy Interventions That Are ‘Market Friendly’ Where There Are Market Failures Are Warranted. Policies should: (a) maintain macroeconomic balance, (b) develop institutions, including property rights and related legal frameworks, so that investors have reasonable expectations of gaining returns from good investments, (c) encourage competition to induce productivity in- creases through an unbiased international trade system and through eliminating legal barriers and lessening transportation and communication barriers to greater competition, and (d) use ‘market-friendly’ interventions that are transparent, rule-based, general and nondiscriminatory such as open auctions, vouchers, subsidies, and taxes to attempt to offset market failures (and directing such policies as directly as possible towards the market failures to limit unintended distortion costs). These considerations imply a critical, but also more selective role for government than in the earlier paradigm. Also involvement in these activities is not necessarily best accomplished by governmental direct production rather than taxes subsidies and regulations concerning disclosure of private information.

3. Current Controversies And Possible Future Developments

Despite substantial current general consensus (Sect. 2), there is neither consensus on every dimension nor on how the paradigm is likely to change.

3.1 Integration Into The International Financial System

International financial movements have expanded rapidly and can swamp foreign exchange movements from international trade. This may provide useful discipline for governments to keep their policies credible. But this also may result in enormous shocks, perhaps fueled by speculative bubbles, which present great difficulties for even the best of governments. The Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s intensified greatly such concerns. Considerable debate continues about the extent to which such problems can be lessened by greater transparency in developing countries finances, more restrictions on capital movements, appropriate sequencing of liberalization efforts with capital flows liberalized relatively late in the process, new systems to assure that developed country investors bear some of the social costs of disruptions originating in large international capital movements, and greater international insurance through international organizations (with attendant moral hazards of encouraging risky behaviors).

3.2 Demographic ‘Windows Of Opportunities’ And Aging Populations

Waves of Malthusian overpopulation fears have featured prominently among noneconomists. But statistical analyses of relations between population growth and economic development do not find important long-run associations. However, recently developing countries are claimed to have transitory (but perhaps lasting several decades) opportunities because aging due to fertility reductions means that they have large working-age populations relative to younger and older populations. Some have attributed a substantial part of the high recent economic growth in some Asian economies to such a ‘demographic bonus’ associated with higher savings and labor force participation and lower health and education expenditures (Asian Development Bank 1997, Bloom and Williamson 1999). There are controversies about what conditions permit developing economies to exploit successfully demographic windows of opportunity to enhance development, rather than being hindered by faster increases in supplies than in demands for labor. Empirical associations for the 1950–1995 period suggest that the conditions embodied in the consensus that is summarized in Sect. 2 increase probabilities of being able to exploit demographic opportunities. Eventually aging populations will imply increased dependency ratios due to a larger number of aged individuals, which will raise issues about intergenerational transfers for retirees and increased health problems associated with aging. Projections suggest that average ages in most currently developing countries will converge substantially to those of developed economies by 2025, so demographic–development interactions will change further.

3.3 Poverty Reduction vs. Growth

The dominant view is that the most effective form of sustained poverty reduction is rapid development that exploits comparative advantages (perhaps including relatively large labor forces), though some safety nets are likely to be desirable for individuals who cannot participate or who suffer dislocations in adjustments towards sustained growth (e.g., Page et al. 1993). But others claim that there are substantial tradeoffs between poverty reduction and the dominant conventional wisdom, at least during transition structural adjustment programs (e.g., the UNICEF critique, calling for ‘adjustment with a human face,’ Cornia et al. 1987). There are inherent productivity-equity tradeoffs in providing safety nets because a sense of entitlement tends to develop that makes such policies hard to change (e.g., political responses to efforts to eliminate food and transportation subsidies) and because they may dampen incentives for work efforts through implying high effective marginal tax rates. Therefore, there is likely to be an ongoing debate about the extent to which such safety nets should be provided and exactly what forms they should take.

3.4 Social Cohesion And Social Capital

There is a growing perception that these are important factors in successful development efforts. If so, then there may be important policy implications from the perspective of the currently dominant paradigm (Sect. 2) because factors that increase social cohesion and social capital are likely to have social returns beyond private returns and thus be under-rewarded by unhindered markets. Establishing the importance of such factors, however, requires the development of more careful integrated modeling estimation approaches. Suggestive anecdotes and associations are currently available, but not persuasive systematic studies that lead to confident identification of causality in the presence of behavioral choices and unobserved individual and community characteristics.

3.5 Paternalism Maternalism, Individual Choice, And Endogenous Preferences

In the immediate post-WWII dominant paradigm (Sect. 1) policy makers and analysts acted as if they knew what was best for the poor in developing countries. If the poor were perceived to hold the ‘wrong’ values (e.g., not working hard enough, wanting too many children, saving too little) it was deemed appropriate to ignore or to try to change their preferences. The current dominant paradigm places greater weight on individual preferences, at least in so far as they are manifested through responses to markets and policies (though limited resources limit the effectiveness of the poorest). There also is recognition of difficulties in making welfare comparisons if preferences are changed. Nevertheless, there are some who appear to wish to impose their values on others regarding, for example, appropriate gender relations. Such concerns raise the analytical question that also has been of increasing interest in general mainstream economics of how to model endogenous preferences and to include them usefully in applied analysis.

3.6 Association Between Economic Participation And Political Participation

An important component of the current economic development paradigm is much greater recognition of active participation of individuals, which, together with discipline of competitive-like markets, provide checks and balances that limit predatory economic behavior. But is an essential component of successful development also a political system with checks and balances? Some argue that some of the most successful East Asian economic development experiences have been under strong autocratic governments (e.g., Korea under Park, China, Singapore). Others note that strong autocratic governments have not been a sufficient condition for successful economic development (e.g., Myanmar, Cuba, the Philippines under Marcos). This controversy about what forms of political systems lead most effectively to development is likely to be ongoing.

3.7 Extent Of Technological Externalities For Human Resources, Population Control, And Environmental Effects And Remedies For Those Externalities

Assertions are widespread that there are substantial positive externalities of human resources and negative externalities of population growth and economic growth on the environment. Yet empirical evidence regarding magnitudes and natures of such externalities is almost nonexistent, at times a priori arguments about what constitutes an externality are confused, and means sometimes advocated to address such externalities do not seem directed well towards the supposed sources of externalities nor do they recognize well the importance of incentives, so they may have substantial distortion costs. There would be high returns to persuasive systematic studies that lead to confident identification of the magnitudes of such externalities in the presence of behavioral choices and unobserved individual and community characteristics (e.g., Foster and Rosenzweig 1995).

4. Conclusion

The economics of developing countries was an integrated part of most major streams of economic analysis in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But in the immediate post-World War II period, economic development was widely seen as sufficiently different in degree to be different in kind from mainstream economics for the developed economies. Developing economies were seen as having such imperfect markets and limited responsiveness to markets by private entities that effective development could be best pursued by (supposedly disinterested and very knowledgeable) policy makers using direct quantitative policies guided by planning models to industrialize in part by protecting their economies from the many negative effects of international markets. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, there was a radical shift in the dominant paradigm concerning economic development. This was in part due to a number of new systematic quantitative studies of a range of developing experiences, importantly including the unprecedented growth in a number of East and Southeast Asian economies. The dominant paradigm at the start of the twenty-first century emphasizes that there is considerable responsiveness to opportunities in developing countries so the incentives created by markets and policies may be critical, that development is much more than physical capital accumulation and industrialization, that human capital and knowledge acquisition may be critical in the development process, that policymakers have limited information and may be rent-seekers, and that a much more nuanced understanding of the nature and response to market failures implies an important but much more limited and incentive-sensitive role for policy. There remain a number of current controversies, such as related to the appropriate degree of integration into global financial markets, the importance of some aspects of social cohesion and social capital, the relation between economic and political participation, and the nature and extent of alleged externalities and other market failures. But for the most part they are considered at least by economists within the framework of this paradigm.

Such a summary of decades of the evolving conceptualization of economic development into a few major paradigms, of course, suppresses considerable heterogeneities of perceptions and approaches among the many economists and policymakers concerned with economic development over the years. But it also captures major dominant features of the evolution of thought on economic development that originally was an integral part of the major approaches to economics, was increasingly separated from main-stream economics in the mid-twentieth century, and then has increasingly converged back with mainstream economics by the start of the twenty-first century. This latter convergence has occurred both because development economics has moved closer to mainstream economics with regard to emphasis on responsiveness to incentives, gains from greater market dependence and limitations of policy interventions and because mainstream economics has moved closer to development economics with regard to such issues as market limitations related to information problems and the broader political, social and cultural context in which economic analysis occurs and policies are made.

Bibliography:

- Asian Development Bank 1997 Emerging Asia: Changes and Challenges. Asian Development Bank, Manila

- Behrman J R, Foster A, Rosenzweig M R 1997 The dynamics of agricultural production and the calorie-income relationship: Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Econometrics 77: 187–207

- Behrman J R, Foster A, Rosenzweig M R, Vashishtha P 1999 Women’s schooling, home teaching, and economic growth. Journal of Political Economy 107: 682–714

- Behrman J R, Srinivasan T N 1995 Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 3. North-Holland, Amsterdam

- Bhagwati J 1978 Foreign Trade Regimes and Economic Development: Anatomy and Consequences of Exchange Control Regimes. Ballinger, Cambridge, MA

- Blitzer C, Taylor L, Clark P 1974 Economy-wide Models in Development Planning. Oxford University Press, London

- Bloom D E, Williamson J G 1999 Demographic transitions and economic miracles in emerging Asia. The World Bank Economic Review 12: 419–56

- Chenery H B, Bruno M 1962 Development alternatives in an open economy. Economic Journal 72: 79–103

- Chenery H B, Srinivasan T N 1988–1989 Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 1 and 2. North-Holland, Amsterdam

- Corbo V, Fischer S, Webb S B (eds.) 1992 Adjustment Lending Revisited: Policies to Restore Growth. World Bank, Washington, DC

- Cornia G, Jolly R, Stewart F 1987 Adjustment with a Human Face, Vol. 1. Clarendon, Oxford, UK

- Foster A, Rosenzweig M R 1995 Learning by doing and learning from others: Human capital and technical change in agriculture. Journal of Political Economy 103: 1176–209

- Foster A, Rosenzweig M R 1996a Technical change and humancapital returns and investments: Evidence from the Green Revolution. American Economic Review 86: 931–53

- Foster A, Rosenzweig M R 1996b Comparative advantage, information and the allocation of workers to tasks: Evidence from an agricultural labor market. Review of Economical Studies 63: 347–74

- Jacoby H 1995 The economics of polygyny in Sub-Saharan Africa: Female productivity and the demand for wives in Cote d’Ivoire. Journal of Political Economy 103: 938–71

- Jacoby H, Skoufias E 1997 Risk, financial markets and human capital in a developing country. Review of Economic Studies 64: 311–35

- Johansen L 1960 A Multi-sectoral Study of Economic Growth. North-Holland, Amsterdam

- King E M, Mason A 2000 Engendering Development: Gender Equality in Rights, Resources, and Voice. Oxford University Press for the World Bank, New York

- Krueger A O 1978 Foreign Trade Regimes and Economic Development: Liberalization Attempts and Consequences. Ballinger, Cambridge, MA

- Krueger A O 1983 Trade and Employment in Developing Countries: Synthesis and Conclusions. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Lewis W A 1954 Economic development with unlimited supplies of labor. Manchester School of Economics and Social Studies 2: 139–91

- Little I M D, Scitovsky T, Scott M 1970 Industry and Trade in Some De eloping Countries. OECD, Paris

- Mahalanobis P C 1955 The approach of operational research to planning in India Sankhya. The Indian Journal of Statistics 16: (Parts 1 and 2)

- Mandelbaum K 1945 The Industrialization of Backward Areas. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Nurkse R 1952 Some international aspects of the problem of development. American Economics Review 42: 571–83

- Page J, Birdsall N, Campos E, Carden W M, Kim C S, Pack H, Sabot R, Stiglitz J E, Uy M 1993 The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy. World Bank, Washington, DC

- Pitt M M, Khandker S R 1998 The impact of group-based credit programs on poor households in Bangladesh: Does the gender of participants matter? Journal of Political Economy 106: 958–96

- Prebisch R 1950 The Economy of Latin America and Its Principal Problems. United Nations, New York

- Ranis G, Fei J 1961 A theory of economic development. American Economic Review 56: 533–58

- Rao V K R V 1952 Investment, income and the multiplier in an underdeveloped economy. The Indian Economic Review. (Reprinted in Agarwala A N, Singh G H (eds.) 1963 The Economics of Underdevelopment. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 205–18

- Rosenstein-Rodan P N 1943 Problems of indusrialization of Eastern and south-Eastern Europe. Economic Journal 53: 202–11

- Singer H 1950 The distribution of gains between investing and borrowing countries. American Economic Review 40: 473–86

- Taylor L 1988 Varieties of Stabilization Experience. Clarendon, Oxford, UK

- Udry C 1994 Risk and insurance in a rural credit market: An empirical investigation in northern Nigeria. Review of Economic Studies 61: 495–526

- World Bank 1991–1997 World Development Report. Oxford, New York