View sample economics research paper on externalities and property rights. Browse economics research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The private market is a common economic mechanism for allocating scarce economic resources in an efficient manner. Imagine a situation where all decisions (when, where, how much, and at what price) relating to producing and consuming every good or service in the society are made by government or a group of individuals. Under such a system, one can expect much wastage, time delay, and lack of coordination among decision entities, which would hamper the smooth and efficient delivery of goods and services. In an ideal world, perfectly competitive private markets are means to achieving the most efficient way of making goods and services available to people, of exactly the quantities they need, at prices they can afford, and at a time and place they need.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

However, it is rare to find such a perfect competitive market. Many conditions are necessary for the smooth functioning of the private market (McMillan, 2002). They are as follows: (a) Side effects of production and consumption are limited, or there are no externalities in production or consumption; (b) there are well-defined property rights to resources, products, and production technology; (c) there exists widely available information about buyers, sellers, and products; (d) enforceable private contracts are present; and (e) the conditions of competition exist. More often than not, one or more of the above conditions are violated in private markets, leading to suboptimal market performances, in terms of product quantity, quality, and prices and consumers’ and producers’ satisfaction. In this research paper, we focus on the first two assumptions of markets: absence of externalities and well-defined property rights. We will first narrate these two concepts and their nuances and then discuss how these concepts are related to one another. Later, we will present the adverse effects on the market system of violating the above two assumptions, as well as regulatory and market means to correct these adverse effects.

Theory

Externalities

Many economic decisions that people make in their day-to-day lives have economic consequences beyond themselves. We can find examples wherein certain people may bear costs or gain benefits from the actions or decisions taken by others, even though they had no role in making those decisions. A profit-maximizing entrepreneur normally takes into account only those out-of-pocket costs that she pays for (i.e., the costs of inputs used in the production process) while deciding how much, how, what, and when to produce goods and services. Such costs are called private costs. To increase profits, the entrepreneur always looks for ways and means—via cheaper technology and inputs of production—to keep the production costs low. It makes no economic sense for her to consider any likely costs of this economic decision inflicted on people or entities other than herself or her firm.

For instance, a farmer has to plow his land to maintain proper tilth of the soil and apply chemicals to kill weeds and pests. Excessive plowing of land with poor soil condition causes soil erosion from his land and contaminates downstream water bodies with soil sediments. The deposition of soil sediment may decrease the water storage capacity of the downstream lake and suffocate fish and other aquatic creatures. Residues from chemical application on the farmland may also end up in the lake, making that water body unsuitable for fish. Both of the above actions on the part of the farmer might mean increased costs of lake water storage and loss of fish production. In the absence of any legal, social, or moral obligation, the farmer upstream has no incentive to reduce soil erosion or chemical application as long those actions bring him economic profits. Nor does the farmer feel responsible for paying for those costs or income losses to downstream water users. Such costs or negative income impacts are called negative externalities or external costs.

Consider another example. There is a private company selling cell phones to customers. The amount of profit the company makes from this product depends on the price and the number of phones sold in the market. The buyers are looking forward to buying a phone at as cheap a price as possible. The price that any given buyer is willing to pay equals the marginal value that he derives from the phone. This marginal value accounts for only his personal (private) value that he derives from it. Note that there could be other buyers who may have already bought this product. When this buyer makes the purchase, he becomes the newest member of the existing network of cell phone users. Each new user enhances the utility or value of the phones owned by all the existing customers. The larger the number of users of a given product is, the greater the ability of all users is to stay in touch with each others. As in the case of negative externality, this private buyer would consider only his private benefits when he makes his purchasing decision. There is no incentive for him to worry about what others might gain from his decision. The other network members are no part of his decision. The benefits that he brings to all other network members are an example of positive externality or external benefit.

In both these examples, when a particular economic decision imposes economic costs on, or generates economic benefits to, a third party, the behavior of the decision maker in the market does not include the costs to, or the preferences of, those who are affected. This means that the private costs borne or private benefits enjoyed by a decision maker are much different (normally lower) from the true costs or true benefits of that decision. The true costs and true benefits are also called social costs and social benefits, respectively. The difference between the social costs and private costs are negative externalities (external costs), and the difference between the social benefits and private benefits are positive externalities (external benefits).

Definition of Externality

Now we are ready to define externality in a more precise fashion. According to Baumol and Oates (1988), an externality is an unintentional effect of an economic decision made by persons, corporations, or governments on the consumption or production by an outside party (person, corporation, or government) who is not part of the original decision. It is evident from this definition that externalities can be present in both production and consumption activities. Also, for an externality to exist, there needs to be a direct connection between the parties through real (nonmonetary) variables. Let us revisit the earlier examples of negative and positive externalities. For instance, it is easy to understand that in a production process, the quantity and quality of a good produced is dependent on the quantities of various inputs produced. In addition, there may be external inputs that, although not chosen by this producer but by someone else, may have a negative or positive impact on the production of the subject product. As in the example of negative externality from farmland cultivation, the total fish production in the downstream lake is not only dependent on fishing inputs employed by the lake users. The fish production is also affected, in this case negatively, by the levels of sediments and chemical residues deposited through the water runoff from the upstream farm. Similarly, the consumption utility or value derived by each cell phone user in the network depends on the number of phones purchased by other users.

Another important aspect of the externality that can be ascertained from the above definition is that the spillover or side effect of one person’s action on the other is not deliberate or is unintentional. An economic agent who is responsible for a given externality has no intention of causing harm or doing good to the other party. The original action is undertaken for one’s own personal gain (e.g., appropriating profit or income from crop production or enjoying certain utility from using the cell phone). The negative or positive spillover effect of such action is strictly unintentional.

Suppose that you are sitting in a room or a restaurant next to a person who is smoking. You may feel uncomfortable with the smell or aesthetic of the smoke. You may also develop a health problem if you are exposed to that smoke over a long time. As long as smoking is allowed in the room, the smoker is engaged in a legally acceptable activity. However, the secondhand-smoke effect inflicted on you is a negative externality. There is physical connection between the smoker and you. On the other hand, let us say every time when you sit near that smoker, he turns around and deliberately blows a puff of smoke right on your face. The effect of this action may be the same as in the first case. This deliberate action, however, would not constitute an externality because it is unintentional. Instead, we would call this behavior a nuisance or even a crime if that person does it every time he sees you.

The above definition covers a specific type of externality. These are external effects that fail to transmit through the market system in the form of prices. When a producer does not account for the external costs she inflicts on a third party, the price that she is willing to accept does not reflect the social costs of production but only her private costs of production. The market prices of such products will be cheaper than otherwise. This is because no private market contract exists between this producer and those affected by external effects that would have required the producer to pay for such external costs. This applies to our cell phone market example also. When a new buyer buys a cell phone, he enhances the value of phones in use for all the existing network users. The seller does not have any ability to go back to the existing customers and to ask for a cut in the additional value accrued to each of them. The seller normally may increase the price on future cell phones sales, knowing that her product is more valuable to customers than before.

In both the examples above, the externalities are caused by real variables (e.g., sediments or phone), the economic (monetary) effects of which fail to transmit through the market process. In the case of negative externality, the full economic effects (costs) of production do not reach the intended buyers (i.e., consumers of farm products) in the market. Instead, a portion of the total costs (i.e., off-farm pollution effect) is felt by a third party (i.e., lake users). Such externalities are called technological or nonpecuniary externalities. In economics, the inability of the market to capture the full social costs and social benefits, therefore sending the right price signal to producers and consumers of a given commodity, is referred to as market failure.

The following modified definition of externality (Lesser, Dodds, & Zerbe, 1997) captures the essence of the above discussion. A technological externality is an unintended side effect of one or more parties’ actions on the utility or production possibilities of one or more other parties, and there is no contract between the parties or price system governing the impact.

The above definition excludes economic side effects that manifest through market prices. For instance, a city municipal government builds a landfill in one of its neighborhoods. The noise and the ugly look of trucks carrying the city solid wastes daily around the landfill disturb the residents. The foul smell from the landfill may become a constant reminder of the landfill’s presence. Those homeowners who can afford to buy houses in better neighborhoods elsewhere may want to sell their homes. As more and more homes start appearing in the market and new buyers may not prefer to purchase a house near the landfill, the home prices in the area will decline. This loss of home value is certainly an unintended economic side effect caused by the city’s decision to build the landfill. However, this effect is carried through the housing market price. Such external effects are referred to as pecuniary externalities. While some people may argue that the loss in the property value is unethical or an injustice, this loss does not represent a market failure problem. In fact, in this case, the housing market seems to have done its job. That is, the market accurately has reflected the lower preference that the new buyers have for homes near the landfill, or that the buyers are willing to pay lower prices.

Effects of Externality

As hinted earlier, the presence of externalities causes a private market to fail. When all the conditions of a perfectly competitive private market are fulfilled, the market is assumed to deliver most efficient results. Profit-maximizing producers allocate their scarce resources in a most efficient fashion. That is, the total quantity of their output meets the condition of marginality: The marginal benefit (i.e., the market price in the case of perfect competition) is exactly equal to the marginal costs of production. Similarly, the amount that consumers are willing to pay (the marginal willingness to pay) balances with the market price offered to them at the margin. This is the market equilibrium level. At such point, the market equilibrates in the sense that the producers’ marginal costs of production are identical to consumers’ marginal willingness to pay (marginal benefit), which is further equal to the market price. At this point, the combined net surplus of producers and consumers is maximized. Both producers and consumers are assumed to have made their resource allocation decisions in a most efficient fashion. This point of market equilibrium is therefore called socially efficient equilibrium.

The above market outcome is based on certain assumptions. The marginal costs of producers (i.e., supply curve) must represent the total or social costs of production. The marginal willingness to pay of consumers (i.e., market demand curve) must represent the total benefit that they derive. That is, the market supply curve should have taken into account both private costs (representing the opportunity costs of all production inputs and the production technology used) and all the potential external costs. On the other hand, the market demand curve should reflect consumers’ private benefits (their own preference and taste) and the external benefits. As we discussed earlier, if there exist external costs and benefits, the private market is not going to capture these additional effects. The resulting market outcome (equilibrium quantity and price) does not reflect the social (full) costs and benefits either. It only captures the private costs and benefits and therefore can only be viewed as a private market efficient equilibrium.

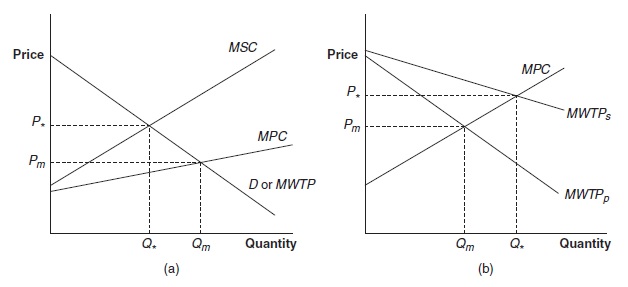

Going back to the problem of agricultural runoff, let us assume that the private farmer faces a downward-sloping market demand, D (Figure 1[a]). The demand curve represents the aggregate marginal willingness to pay of all consumers in the market, MWTP. The farmer has a marginal private cost function (supply curve), MPC. Assume that every unit of agricultural output imposes certain marginal external costs, MEC, on the lake users. Thus, the agricultural production comes at marginal social costs, MSC, to society. Note that

MSC = MPC + MEC.

In the private market, where she has no obligation to consider the external costs, the farmer produces Qm units of output at a unit price of Pm (i.e., at a point where MPC = MWTP). This is efficient only from the view of the private producer, and therefore we call this level private market efficient equilibrium (Qm, Pm).

The above equilibrium, however, is not socially efficient because the underlying cost function does not include the external costs. The socially efficient equilibrium (Q*, P*) should occur at a point where MSC = MWTP. It is interesting to note two points here. The socially efficient equilibrium quantity is lower than the private market efficient equilibrium quantity. Also, the socially efficient equilibrium price is higher than the private market efficient equilibrium price. The private market oversupplies the good. That is, Qm > Q* and Pm < P*. A production in excess of socially efficient production means larger pollution loading downstream. Because the external costs are left out of the producers’ cost equation, consumers will enjoy a lower market price.

Now, consider the cell phone example that involves external benefit. Assume that the cell phone company faces a supply or marginal private cost function, MPC (Figure 1[b]). We assume that there is no external cost resulting from the phone production. All cell phone users face a combined private marginal willingness-to-pay curve, MWTPp. That is, this relationship includes only the private benefit portion of all network users. We know that the each user (or phone) adds certain external value to all customers, MWTPe. Thus, the (total) social marginal willingness to pay of each additional cell phone is MWTP;.

MWTPs = MWTPp + MWTPe.

We can see that in this case, the private market produces only Qm at a private market equilibrium price of Pm. However, because of the presence of external benefits, the socially efficient market equilibrium occurs at Q* and P*. Note that, unlike in the case of external costs, when there are external benefits, the market underproduces goods and services (i.e., Qm < Q*). Because the consumers’ true preference or value is not fully revealed in the marketplace, the private market equilibrium price is lower than the socially efficient equilibrium price (i.e., Pm < P*). One might argue here that consumers are better off with lower market price. That is true; however, the network as a whole will end up getting a smaller number of cell phones than what is socially optimal if the producer is not in a position to capture the full value of each marginal phone supplied in the market. This is particularly a problem in a special class of market goods, called public goods, which we will discuss later.

Causes of Externality

The question that naturally arises is why externalities exist in the market. In the previous examples, we see that the producer has no incentive to compensate the victims of downstream externalities, nor do cell phone consumers have an incentive to pay for the external benefits they enjoy from each additional network user. In other words, the economic decision makers in each case have no incentive to internalize the external costs or benefits. The two most fundamental reasons of externalities are (a) nonexclusivity and (b) high transaction costs.

First, externalities are often associated with nonexclusion or nonexclusivity characteristic of a resource or an economic asset. Consider again the example of our upstream-downstream agricultural pollution problem discussed earlier. There are no legal, social, or technological barriers that prevent the farmer from loading sediment and chemicals into the downstream lake. That is, the farmer has uncontrolled access to the lake. Under the existing legal or social norm, the lake users cannot exclude (nonexclusivity feature) the farmer from dumping pollutants into the lake. The ownership of the lake is not clearly defined. Similarly, in the case of the cell phone example, as each new buyer enters the market, the existing customers benefit from the additional network sociability or social interaction. There is nothing in the marketplace that prevents the existing customers from enjoying that extra benefit unless the phone company decides to switch off their connectivity. However, such practice might be too costly for the phone company. Again, this is a case of nonexclusivity.

Figure 1. Private and Socially Efficient Market Equilibria: (a) The Case of Negative Externalities; (b) The Case of Positive Externalities

This brings us to the second condition of efficient markets, mentioned in the beginning of the research paper: well-defined property rights. The degree to which the users of a resource or property can exclude others depends on the nature of property rights. The right to own and use a property, including the right to exclude others from using it, influences whether and how much the external costs and benefits are internalized and transmitted through the market price. In the next subsection, we will explore the role and significance of property rights in more detail. At this point, it is enough to note that one of the reasons the lake users are forced to bear the burden of the negative externality is that they lack a well-defined property right to the lake and, therefore, lack the right to exclude upstream farmers from dumping pollutants to the lake.

The second reason externalities exist is the high transaction costs. According to Arrow (1969), transaction costs are the costs of running the economic system. Even when the right of exclusion exists, the property owners may not be able to exercise that right due to high costs of transaction. The transaction costs include the costs of gathering necessary information, costs of reaching an agreement with the other decision makers in the market with regard to one’s right, and the costs of enforcing such agreement. For instance, in the case of lake users, the costs of proving that the pollution loading originates from the upstream farmer may be high. This is especially true if the pollution problem is not from just one particular farmland (a point source pollution) and, instead, from a large number of farm lands (a non-point source pollution). There are additional costs of reaching a private agreement with the upstream farmers and making sure that they bear the full costs of the pollution or take action to abate pollution. Basically, the transaction costs are the costs of exclusion. The lack of, or ill-defined, legal right to exclude upstream farmers means that the downstream lake users have high transaction costs of exclusion. These costs may be too high for downstream users to try enforcing their right against upstream farmers.

The amount of transaction costs depends on the technical and physical nature of the externality and the number of parties involved in a given market transaction. In many cases involving negative or positive externalities, there may be technical or physical barriers in reaching an agreement. Certain pollution may be hard to detect with the available technology for measurement. The external costs of such pollution may not show up in the short term but only in a distant future. A precise estimation of such costs is often difficult. External benefits may pose similar problem. Putting a value on the network-wide aggregate incremental benefit is not easy in the case of the cell phone example. Obviously, the larger the number of parties involved on either side of a market transaction, the higher the transaction costs of gathering information, reaching the agreement, and enforcing the agreement.

Whether a producer who is responsible for certain external costs is willing to bear or internalize the externality depends on whether she is able to transfer that extra cost on to her consumers. For her to do so, the market price that the consumers are willing to pay must be higher than the private costs of producing the good and the external costs. If the market price is not high enough to cover both the private costs and external costs, the producer has no option but to ignore the latter, which she can easily do because she enjoys nonexclusive access to the downstream environment. Thus, the externality comes into existence when the costs of internalization exceed the gains from internalization.

Property Rights

According to Demsetz (1967), property rights are an instrument of society that accords rights to an individual to own, use, dispose, sell, and responsibly manage certain property or economic assets. These rights may be expressed through laws, social customs, and mores. The rights give its owner an uncontested privilege to appropriate benefits from the designated property or asset. The rights also protect the owner from other individuals of the society from encroaching on this asset. The bundle of rights normally comes with certain responsibility so that the owner may not put the property to legally and morally unacceptable uses.

A clearly defined property right lends its owner the ability to appropriate full benefit from its use or management. For a private market to operate efficiently, this is a key requirement. When a producer makes his decision to invest in factors of production (land, labor, and capital), he forms an expectation that he gets the full reward for his effort. One of the necessary conditions that make this possible is that he possesses full rights to all the factors and the final product until he decides to dispose his right to that product in the marketplace for a due compensation (i.e., a reasonable market price). Such a guarantee of right gives the owner an incentive to invest in the asset, manage it in a most efficient fashion, and dispose of it only when he thinks it is the best time. Therefore, the conventional economic wisdom holds that privately owned resources are put to most efficient uses. If all privately held scarce resources are used efficiently, the society as a whole benefits from that process as well.

In order for property rights to serve their function well in the market, the following requirements must be met:

Property rights must be well defined. There should be no ambiguity as to who owns a given economic asset. The clear identification of ownership gives its owner a right to make decisions relating to the asset’s growth, maintenance, use, and disposal. The ownership can be private, communal, or state. A private owner may be an individual or a firm. The car you legally own is an example of private property rights. The farmland owned by the farmer is another example of private property rights. A patent right owned by a private firm to a certain technological innovation or product is also a private property right. A communal ownership is normally a group of owners, each member of which will have certain use and access rights and responsibilities. Communal ownerships are common among traditional societies in the case of forests, grazing land, water, rivers, and other natural resources. A state ownership puts the resource or asset in the control of a government agency. The state may own and use the resource exclusively or may share a portion of the rights with its constituents or citizens. For instance, a national park in the United States is owned by the U.S. government and managed by the National Park Service. The parks’ certain uses (recreation, research, or mining in the park) may be open to the general public, subject to certain rules and regulations.

Property rights must exclusive. The owner of the property rights must be able to exclude others from using it. This exclusivity lends the owner an ability to enjoy the full benefit from it and be able to recover the entire costs of operating it. As discussed in the earlier sections, exclusivity also prevents an external individual from causing harm to the owner (i.e., externality).

Property rights must be enforceable. There must be clear legal or social guidelines as to how the society deals with a violation of one’s property rights. If somebody encroaches upon the farmland, the farmer must be able to bring the violator to justice, meaning that the latter is evicted from the property and made to pay the cost of evictions and any economic damage associated with the encroachment.

Property rights must be transferable. The owner must be able to dispose the property whenever he wants and at a price that he can reasonably get from the market, without much restrictions. If the property is divisible and the owner can dispose any portion of it as needed, such property right represents full transferability. The owner can more effectively manage his or her resource.

The Case of Weak Property Rights: Open-Access Resources and Public Goods

We will find many instances in the market system where economic resources do not operate under strict private property ownerships. In fact, we already have introduced several examples of these resources. When the property rights are ill defined, weak, or absent, multiple users will claim ownership or access rights to such resources. For instance, both upstream farmer (though unintentionally) and downstream lake users can access the lake and have competing uses for the same. Cell phone network users can enjoy the additional benefits generated by each additional phone buyer. The network provides a certain value component (increased sociability) that is open to all users to enjoy without excludability. Thus, when the property rights cannot be assigned or defined, the problem of nonexcludability arises. As we said earlier, nonexclusivity is one of the determinants of externality and market failure.

Two types of natural and economic resources and services suffer the problem of nonexcludability: open-access resources and public goods. These two resource types differ in the way their users interact with each other. We will discuss each of these resource types individually and the unique problems they pose for their owners and society in general.

An open-access resource is that resource to which users have uncontrolled access, leading to competition among users. That is, the consumption or extraction of the resource by one user reduces the quantity available for others. Thus, the resource is divisible and subtractable. In other words, you will find rivalry among its users. Thus, open-access resources are nonexclusive, rivalrous in nature. Fishery resources in open international waters are a good example of open-access resources. You may not find many strictly open-access resources today. A large number of resources are placed under government or community control. However, for all practical purposes, their users may have open and unlimited access to them. Such resources do suffer to some degree the problem of nonexclusivity and competition among users. Grazing lands, rivers, government forests, fishing grounds, national highways, and public parks are some examples.

Users of an open-access resource basically lack incentives to exercise caution or restraint in its use. Because other users cannot be excluded, a given user trying to conserve or enhance the resource may not realize the full benefit of his action. Therefore, the common motive you observe among the users of open-access resources are “use the resource while it lasts,” “grab the resource as quickly as you can,” and “grab as much of the resource as you can.” Such competitive behavior will lead to overexploitation of the resource. This overexploitation problem is what Hardin’s (1968) famous expression, the “tragedy of the commons,” refers to. Each user will try to maximize his or her own self-interest (i.e., to the point where the private gains from the additional unit are equal to the private costs of the additional unit). In this process, each user may negatively affect the productivity of the resource or costs of extraction of the resource for all other users. The impact of each user’s action on oneself may be insignificant, but the effect of one user’s action on all users combined could be quite substantial. In Hardin’s words, the “freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.”

To illustrate the above problem, let us consider a common-pool ground water aquifer. Farmers who own land on the ground directly above the aquifer can easily access the aquifer and extract water. Because it is accessible by only those who own land above it, the aquifer is normally considered as a common-pool resource (i.e., a resource owned by a definite community of people) and is not strictly an open-access resource. However, those land owners will have uncontrolled freedom of access to it and therefore could construct as many wells as they need.

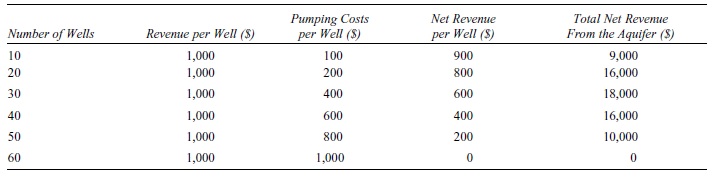

Suppose that each well can serve two acres of land and generate a total gross return of $1,000, net of all other but the pumping cost. The cost of pumping is an increasing function of the pumping depth, which in turn is an increasing function of the number of wells on the aquifer. That is, as the number of wells increases and more water is withdrawn, the water table goes down and the pumping lift and the cost increase. See Table 1 for the costs of pumping per well. Looking at the net revenue column, you will see that the net revenue per well gradually declines and reaches zero when the number of wells is 60. The aggregate net revenue from all operating wells combined, though, is maximized at 30. This level can be considered the socially efficient level of extraction (Q»). However, because the landowners have uncontrolled access to the aquifer, their tendency is to dig wells as long as each additional well brings a positive net profit (i.e., 60 in this example). This level can be considered the private market solution (Qm). Note at the market equilibrium level, the aggregate profit earned from the resource is zero, an indication of most inefficient economic overexploitation.

Now we will turn to the case of public goods. Like open-access resources, public goods also suffer a nonexcludability problem. The difference is that there is no rivalry among the users of public goods. The same quantity of the good made available to one person is automatically available to all users. That is, users jointly consume or enjoy the good. This refers to the indivisibility quality of the good. In the words of economist Paul Samuelson (1954), “Each individual’s consumption of such a good leads to no subtractions from any other individual’s consumption of that good” (p. 387). Common examples of public goods are clean air, open landscape, biodiversity, public education, national security, a lighthouse along the beach that the mariners use, flood protection services, and ecological services. The word public here means that it is available to all users (the public) at the same time and at the same quantity.

There can be privately provided public goods. For instance, radio signals or network television services provided by private companies are also public goods, although they are paid for by private companies. Who (private or public entity) pays for a good does not make it a “public good,” but that it is made available for the general public in lump sum does.

An important feature of public goods is that they possess a large degree of external benefits. A few mariners may decide to invest in building a lighthouse so that they can safely navigate around the coast. However, this lighthouse can be easily used by those mariners who may have not paid for it. Thus, the efforts of those invested in the lighthouse are yielding external benefits to noninvestors also. The nonexclusivity problem makes it difficult for the original investors to recover compensation from the noninvestors. The costs of excluding the latter may be exorbitant.

The nonexcludability (lack of property rights) and the presence of external benefits pose a unique problem in the case of public goods: the problem of free riding. Free riding refers to enjoying the benefits of others’ efforts without paying for them. Once a public good or service is provided, users have no incentive to contribute toward the cost of the service. In a private market, you may not be able to find a sufficient number of buyers who can pay enough to make such services or goods available at socially efficient levels—that is, the problem of under-supply as discussed in the case of positive externality (Figure 1[b]), Qm < Q*. Again, this is another case of market failure, caused by the presence of weak property rights and positive externalities.

Table 1. Income and Costs From an Open-Access Groundwater Aquifer

Policy Implications

The presence of externality and ill-defined property rights lead to market inefficiency (i.e., either undersupply or oversupply of certain goods and services). There are several policy options for correcting this problem. These policy options fall under two broad categories: property right solutions and government interventions.

Property Rights Solutions

We had argued that one of the reasons for the presence of externalities was the absence of well-defined property rights and the attendant nonexclusivity. So to resolve the externality problem, economists suggest that we directly target the weak property rights. This approach is a private market solution or property right method. Nobel laureate economist Ronald Coase (1960) articulated this approach, which is now popularly known as the Coase Theorem. The essence of the theorem is simple: If a clear property right over an environmental asset involving externality is specified, a negotiation between the two private parties (originator and the victims of the externality) will emerge and eliminate the externality. Irrespective of who originally has the property right over the environmental asset, a private market for trading the externality will evolve.

With the lake example, the private right over the lake may be given to either the upstream farmer or downstream lake users. If the farmer has the right, it makes sense for the lake users to enter an agreement with the farmer to have her cut back the pollution. Lake users will have to compensate the farmer toward the pollution control costs. This of course is based on the assumption that such monetary compensation is lower than the gains from the avoided damage to the lake via pollution control. Similarly, if the lake users have the property right, the farmer will have to pay suitable compensation to the lake users to accept a certain amount of pollution and associated damage. Thus, in either case, a more efficient private market outcome will result, with reduced pollution and lower external costs. What is happening here is that the clearly defined property right forces the parties involved to internalize the externality.

The above market solution will work only under certain conditions (Field & Field, 2009). The transaction costs of establishing and enforcing the market agreement between the parties must be reasonably low. A higher transaction cost might discourage either party from entering into an agreement. If the number of parties involved is large or it is too hard to prove the pollution damage impacts, the transaction cost is normally high. With a large number of parties involved, there is also a possibility of a free-rider problem. Furthermore, for technical, social, and political reasons, in some cases it may be hard to establish clear property rights.

Political scientist Elinor Ostrom (1990), who received a Nobel Prize in economics in 2009, argues that communal property rights can also eliminate overexploitation and reciprocal externality in the case of open-access resources. The Ejidos system of community forest management system in Mexico is a good example of a communal property right system. Almost 8% of the country’s forest lands are owned and managed by community organizations. Rules of access and profit sharing are formed and enforced by the communal body and recognized by the government. Community-managed sacred groves found in other countries serve a similar role but on a more informal basis. A similar group or community approach is possible in the case of public goods. For instance, home owners form an association or club to manage common facilities in their residential area (e.g., playgrounds, recreational facilities, lake). Homeowners will then be required to pay for these common services with a monthly fee or on a pay-per-use basis. Such public goods and services now become club goods.

Finally, government may take open-access resources into its control and place full or partial restrictions on access and use rights. The goal here is to eliminate competition among users and possible externality imposed on each while consuming the resource. In the case of public goods, in the overall interest of the society, the government may bear the full cost of supply and operation instead of relying on private markets. National defense, public radio and television services, and public education are some examples of this approach.

Government Interventions

Privatizing open-access resources and government provision of public goods may not work effectively in all situations. We saw a number of reasons why it may be hard to establish property rights over resources and thereby internalize externalities. In those cases, the government can directly intervene into private markets using a variety of policy instruments, to influence the production and consumption behavior of economic agents. There are two types of government interventions: command-and-control policies and market-based policies.

The command-and-control policies will impose legal restrictions on producers’ and consumers’ behavior. Formal legislation may be enacted by local, state, and federal governments specifying whether and how much pollution is allowed. Private factories spitting smoke into the atmosphere and discharging waste into water bodies may be asked to install certain pollution abatement devices at their site. These are called technology standards. Or, the government may set a maximum limit or performance standard on the quantity of emissions leaving their plants during each time period, which may be achieved through any means of the polluters’ choice. These are called emission standards. In the case of open-access resources such as fisheries, ground water aquifers, and forests, the government may put legal restrictions on quantity extracted, timing of extraction, and nature of extractions. Automobile owners may be required to install certain emission control devices on their cars. These command-and-control policies require proper enforcement mechanisms, including provisions for a penalty on those who fail to comply with the law. This approach is justified on the polluter pay principle and is viewed as a fair approach by many, including environmentalists. While this method is easy to administer from the government agency point of view, it may work out to be a more expensive way of internalizing externalities.

Market-based approaches to internalizing externalities may overcome some of the limitations of command-and-control approaches. Again, there are several options: taxes, subsidies, and tradable permits. These approaches give economic agents higher decision flexibility, make them weigh the costs of creating an externality (e.g., an emission tax) and the costs of not doing so (e.g., emission abatement), and help them choose the most cost-effective means of internalizing the externality. Under taxes, producers responsible for a certain externality will be required to either pay a tax on every unit of pollution (emission tax) or production output (output tax) causing that externality or invest money in pollution control. Under this policy, the producer will have internalized the externality either by lowering the emission and therefore bearing the costs of abatement or by paying taxes on uncontrolled emission, which may be used to compensate the victims. A subsidy is another approach whereby government will encourage socially desirable behavior (pollution control or reduced resource harvesting) among private economic agents.

Tradable emission permits and harvest quotas are more recent and innovative market approaches that create private rights over emission or resource consumption. The popular cap-and-trade system for greenhouse emissions or sulfur dioxide emission is an example of this policy. Under this policy, each polluting firm will have a certain number of permits, each permit being equal to the right to emit a unit of pollutant. The firm can use all the allotted permits, save some and sell the unused permits in the market, or purchase some permits from other permit holders. Each firm will compare its own marginal costs of abatement with the market price of the permit. Those firms whose marginal costs of abatement are higher than the permit price can save money by purchasing permits in the market and, therefore, by not having to lower the emission as much. On the other hand, firms whose marginal costs of abatement are lower than the permit price can make a profit by lowering their emissions and by selling the unused permits at a price that is higher than their marginal abatement costs. After trading, all the firms in the market (buyers and sellers of the permits) will have adjusted their respective emission levels such that their marginal abatement costs are made equal to the permit price and, therefore, are balanced across all sources. This phenomenon is called the principle of equimarginal costs. In this process, the permit trading system will have moved the emission control responsibility in the market from high-cost (less cost-efficient) firms to low-cost (more cost-efficient) firms. As a result, the overall costs of emission control (i.e., costs of internalizing the externality) will be minimal.

Individual transferable quota programs for fisheries and water trading between urban and agricultural water users are other examples that fall under this category. A long-term advantage of this policy approach is that the economic agents will have an incentive for technological innovation. The permit or right system induces them to invest in innovative and cost-effective means of pollution control or harvest methods. Those who innovate find that they do not require all the allowed permits and rights and can sell the unused ones in the market for a price.

Conclusion

In this research paper, we learned that the presence of externalities and weak property rights renders private markets inefficient. When economic agents cause negative externalities, the market will produce above what is socially optimal or efficient, leading to wastage of production resources, excessive output, and undesirable external impacts. Negative externalities associated with production or consumption will go unpriced in the market. On the other hand, in the case of positive externalities, the market will underproduce because consumers may not pay for the external benefits created as a result of someone else’s action.

Externalities and property rights are related concepts. The primary reasons for externalities are nonexclusion and high transaction costs. Nonexclusion arises from weak or absent private property rights over resources or market services. Open-access resources and public goods are two common examples where weak property rights prevail and externalities emerge.

The presence of externalities and weak property rights calls for government intervention. One approach is to fix the weak property rights, which of course may not be possible in all cases. Properly defined property rights will force private agents to internalize externalities, moderate their consumption and production levels, remove undesirable conflict among users (open-access resources), and eliminate freeriding incentives (public goods). Direct government intervention, with different degrees, is another popular means to correcting externalities. No one size fits all.

Bibliography:

- Arrow, K. J. (1969). The organization of economic activity: Issues pertinent to the choice of market versus nonmarket allocation. In U.S. Congress, Joint Economic Committee (Ed.), The analysis and evaluation of public expenditures: The PBB system (Vol. 1). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Baumol, W. J., & Oates, W. E. (1988). The theory of environmental policy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1-44.

- Demsetz, H. (1967). Towards a theory of property rights. American Economic Review, 57, 347-359.

- Field, B. C., & Field, M. K. (2009). Environmental economics: An introduction. Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 168, 1243-1248.

- Lesser, J. A., Dodds, D. E., & Zerbe, R. O., Jr. (1997). Environmental economics and policy. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- McMillan, J. (2002). Reinventing the bazaar: A natural history of markets. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Samuelson, P. A. (1954). The pure theory of public expenditure. Review of Economics and Statistics, 36, 387-389.