Sample Mode of Production Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Karl Marx’s term Produktionsweise is usually translated into English as ‘mode of production,’ but it might be more simply rendered as ‘way of producing.’ Never precisely defined in Marx’s work—yet arguably at the center of it—Produktionsweise refers to both a form or structure and a way of producing. One might say that Marx’s object in Capital was to show how the first—a particular structure of unequal power and wealth—was both the cause and the result of the second—men and women pursuing their individual ends under capitalist constraints.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

One of the notable aspects of the capitalist mode of production is, according to Marx, its inherent instability. As individuals pursue their projects, there comes a time when the capitalist system can no longer be reproduced. At that point, revolution appears on the horizon, and the entire mode of production will eventually be transformed—capitalism being replaced by socialism, socialism by communism.

Even though Marx referred at times to other modes of production—primitive communist, the ancient, Asiatic, feudal, socialist, and finally modern communist—his only developed work was on capitalism. On what would come after capitalism, he offered only the vaguest of outlines; it would fall to Lenin and others to construct actually existing socialism. And on what came ‘before,’ Marx sometimes reflected only the European prejudices of the nineteenth century. He thought the Asiatic mode of production was inherently static and would waken to change only through the effects of Western imperialism.

The grand evolutionary teleology in Marx’s view of history—the circular but progressive spiral from primitive to modern communism—accounts for much of the political appeal of Marx’s ideas. Ironically, that appeal was felt mainly in countries on the periphery of capitalist development; in such locations, the notion of the stages of history appeared to offer a road map to a better future, a way to skip ahead. But this aspect of Marx’s work also accounts for its ambivalent reception among social scientists who, even if they acknowledged an inevitable political component in their work, looked to the court of evidence as the final arbiter of knowledge.

As Marxism began to provide the legitimating ideology of socialist states in the twentieth century, it tended to stagnate there. In the capitalist West, however, Marx’s ideas received critique and development, principally during periods of crisis in the world capitalist system, namely during the Great Depression of the 1930s and again during the late 1960s and 1970s. During the second period in particular, the notion of mode of production became the subject of wide-ranging discussion.

In the field of anthropology this was particularly true in France where, under the influence of structuralist philosopher Louis Althusser, a wide-ranging conversation took place among scholars such as Claude Meillassoux, Pierre-Philippe Rey, Maurice Godelier, and Emmanuel Terray. Below, I attempt to summarize the lasting legacy of this conversation. I do so, not in the structuralist vocabulary of the time, but in reference to what I regard as the clarifying, later work of British analytical philosopher G. A. Cohen.

What, then, is a mode of production? Perhaps the simplest answer is that it is a model of certain basic regularities that hold across and therefore define historical epochs. At the heart of these regularities is the interrelationship between technology in some broad sense and social stratification. According to Marx, the first—Produkti krafte or productive forces—determines the second—Produktions erhaltnisse or relations of production. These two constitute the base of a mode of production, which, in turn, determines the superstructure.

1. Productive Forces

Productive forces are anything that can be used in productive interaction with nature. On this reading, productive forces are not simply raw materials or tools; more inclusively, they are human skills, productive knowledge, and even the technical aspects of human cooperation in the labor process. These factors Marx considered as equally ‘material’ in that they can all be utilized to produce. But most current readers would probably classify objects, knowledge, and the technical aspects of cooperation as variously material, ideal, and social.

The most striking aspect of productive forces has been their tendency to expand over human history. In the most general sense, the anterior cause of this tendency appears to be located in human nature itself. Humans everywhere develop their powers and skills in a continuous dialectic with nature, and presented with a choice between more and less efficient means of production, humans everywhere (with certain limited exceptions) choose the first.

If productive forces have tended to expand, this fact can only be established at a world level. Some societies have stagnated; some have even experienced local declines in the level of productive powers. As will become clear below, relations of production can prevent technical development beyond a certain point. For any particular society in stasis, there is no reason to believe that new social relations compatible with the further expansion of forces must develop. In fact, technical knowledge tends to diffuse from place to place, and typically the most ‘advanced’ societies are not the ones that give rise to the next development. Rather, peripheral groups that are the recipient of the productive knowledge of their more ‘advanced’ neighbors often leapfrog ahead.

Just what determines the ‘level’ of development of productive forces should be considered. A society’s mass of productive forces is determined by two factors: first, average productivity of labor, and second, population. The product of these two factors yields the level of productive forces. In this formulation, population itself is not a productive force, yet it enters into the determination of the level of productive powers.

2. Relations of Production

Relations of production are not, as the English phrase suggests, simply the social relationships formed in the process of production. Rather, they are the de facto power relationships that both underlie and are the result of the division of the fruits of a society’s total labor. Household head vs. dependents, chief vs. subjects, master vs. slaves, feudal lord vs. peasants, capitalist vs. workers—relations of production are basic asymmetries of power grounded in the organization of material life. In capitalism, relations of production rest upon actual control over productive forces in the process of production, but in other modes of production, this is not necessarily so.

In relation to the last point, consider the contrast between capitalism and precolonial chiefdoms in Africa. Capitalists put the production process into motion; they or their representatives oversee and supervise in order to ensure that a profit is produced at the end of the work cycle. In many chiefdoms, chiefs did not control the production process itself. Yet, having produced, subjects brought tribute, the fruits of their own labors, to the chief. This contrast illustrates the fact that relations of production definitionally correspond to the basic structures of power in a society—however that power is constituted, whether by economic, coercive, or religious means (or some mix of these). As will become clear below, it is the superstructure that clothes and stabilizes power in particular cultural and organizations forms.

Why do productive inequalities occupy a central place in Marx’s thought? The answer is that they locate the basic divisions within any society, the lines of potential opposition—of contradiction. Marx saw these as the potential fault lines along which tensions tend to build up, are routinely dissipated by small readjustments, and are sometimes violently resolved by radical realignments. These fault lines are structural; they do not necessarily lead to actual struggle and conflict (indeed, the function of the superstructure is precisely to prevent such occurrences). Nevertheless, contradictions always exist as potentialities; they lie just below the surface.

3. Forces Determine Relations

Ordinarily, if a factor X is said to determine factor Y, then X is taken to cause Y. Given X, Y is uniquely specified. Transferred to Marx’s scheme above, this understanding of determination yields what has been called vulgar Marxism. Such an interpretation can be supported by some of Marx’s own, more incautious summary statements: ‘The handmill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam mill society with the industrial capitalist.’ Empirically it is clear that the same technology can exist in different modes of production.

A great deal of effort has been expended by commentators to explicate Marx’s notion of determination—from examination of dialectics to, in Engels’ phrase, determination only ‘in the last instance.’ Probably the best way to clarify Marx’s claims is to note that they are forms of functional, not causal explanation. Immediately, a distinction needs to drawn between functional explanations and the theoretical school known as functionalism in sociology and anthropology: Marx used functionalist explanations, but he was not a ‘functionalist’ in the second sense.

Functional explanations have a distinct logical form in which the effects of a trait enter into the explanation of the presence of that trait: for example, when Y’s presence is partly explained by some positive consequence Y has for X. In such a case, X can be said to determine or ‘select’ Y because of Y’s effect on X.

Marx believed that the level of productive forces selects relations of production. For any given level of development of forces, there is only a limited set of relations possible—namely, those that are compatible with and in fact promote the further development of forces. Here, X hardly causes Y in a one-way pattern of determination. Rather, the reverse is closer to the truth: it is Y’s effect on X that are paramount. Particular relations cause expansion in the forces. Herein lies the rub, however. As forces expand, they reach a level that is no longer compatible with the existing relations of production. At that point, according to Marx, revolution becomes a possibility. In this way, continuous incremental change (in forces) is mapped onto occasionally discontinuous revolutionary change (in relations) in the base of modes of production.

4. Bases Determine Superstructures

One of the important contributions of G. A. Cohen was a clarification of the notion of superstructure. If Marx claims that the base or, more precisely, relations of production determine the superstructure, then a definition of relations and superstructure must be found in which the two are clearly distinguished. The difficulty is that power as we find it in any social formation is encased in particular cultural and legal concepts, i.e., superstructural notions. It was for this reason that Cohen defined relations of production as the de facto distribution of power. Every culturally encoded right, he argued, can be matched with a de facto power. And it is de facto power that determines culturally specific notions, rather than the reverse.

One important effect of this definitional move is to place the long-term dynamic of a mode of production outside of culture itself. Eventually, culture corresponds to de facto power rather than the reverse. But in a shorter-term sense, it places culture at the very center of the analyses of modes of production, for it is precisely the superstructure that defines and stabilizes relations of production. Once again, the logic of functional explanation turns the expectations of ordinary language upside-down. If something is described as having a base and a superstructure, we think of the base as a foundation. It supports the superstructure; without the foundation, the superstructure would fall to the ground. Yet, the logic of functional explanation requires the opposite: it is the superstructure that ‘makes’ the base.

To adapt a visual image from Cohen (1978), consider the following: Four pieces of wood of the same length are driven a little way into the ground. They stand, but they are easily blown over by a strong wind. A top is attached to the four struts such that the whole becomes a table. The struts, now legs, stand solidly upright. They do not wobble in the wind. Of the tabletop, one can say: (a) it is supported by the legs, and (b) its very existence is required for the legs to be legs. Without the top, the legs would not be legs—only sticks of wood of such-and-such a length. Here we have a building whose base and superstructure relate in the proper way.

The conclusion to this line of the thought (heretical to some Marxists) is that Capital is an analysis of the capitalist superstructure—the set of culturally specific and legally encoded meanings and practices that tend to stabilize capitalist relations of production. In a comparative sense, this conclusion is crucial since it sets capitalism on the same analytical plane as any other mode of production. On this view, the analysis of modes of production becomes a matter of locating effective power difference over material production as they are reflected in differential control over the total social product and analyzing the meanings and practices that tend to reproduce such powers.

5. Functional Alternatives

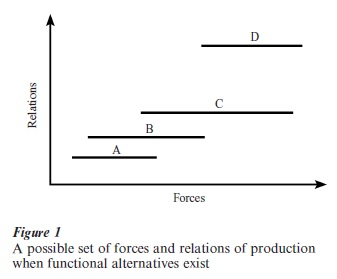

If this reading of Marx’s notion of determination solves many conceptual problems, it also creates others in the application of Marx’s ideas. Carl Hempel and others have called attention to the difficulties of actually carrying out functional explanations. Not the least of these stem from the problem of functional alternatives. That is, there is often more than one Y (Y₁ , Y₂ , Y₃ …) that can fulfill any given function. That being so, the particular presence of Y₁ , say, cannot be explained simply by referring to its function, for Y₂ or Y₃ could have served the same need.

The critical question becomes: what is the size of the set of functional alternatives? Implicitly, Marx appears to have believed that alternatives are quite limited—typically to the set of one. Consider such a limiting case. For each level of development of productive forces, there is only one set of relations possible. History therefore proceeds in a series of discrete steps from A to B to C. Both the past and the future are specified—socialism is inevitable because it is supposedly the only economic system consistent with highly developed forces.

A different story emerges if the number of functional alternatives is even moderately few. If several different sets of relations of production are compatible with any given level of forces, then the grand design of world history becomes considerably more complex. One possible trajectory in Fig. 1, for example, would be A to C to B to D. In this reading, the future looks considerably more open. There may indeed be functional alternatives to socialism—if indeed socialism as we have known it is compatible with developed forces.

6. Conclusion

The notion of a mode of production is a deliberate simplification. It provides a model of certain central relationships that define epochal forms. As such, the analysis of modes of production cannot substitute for the examination of particular cases in specific spatial and temporal contexts. In this sense, modeof-production analyses do not constitute historical explanations.

In a larger sense, however, the concept of modes of production furnishes the necessary scaffolding without which all local historical explanation would be impossible. Comparison and contrast, whether explicitly or implicitly carried out, depend upon a common framework. This is what Marx’s notion of ways of producing provides: a unified theory for viewing human society and history.

Bibliography:

- Althusser L, Balibar E 1970 Reading Capital [trans. Brewster B]. Pantheon, New York

- Anderson P 1974a Lineages of the Absolutist State. New Left Books, London

- Anderson P 1974b Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism. New Left Books, London

- Aston T H, Philpin C H E (eds.) 1985 The Brenner Debate: Agrarian Class Structure and Economic De elopment in Pre-Industrial Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Cohen G A 1978 Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Donham D L 1999 History, Power, Ideology: Central Issues in Marxism and Anthropology, 2nd edn. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Kahn J S, Llobera J R (eds.) 1981 The Anthropology of Pre-Capitalist Societies. Macmillan, London

- Moore S 1980 Marx on the Choice Between Socialism and Communism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA