Sample Economics Of Discrimination Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

1. Discrimination

In the abstract, ‘discrimination’ refers to distinctions or differentiation made among objects or individuals. In economics, as in ordinary parlance, discrimination carries a pejorative connotation. The term is generally reserved for distinctions that are socially unacceptable and economically inefficient. Economic theories of discrimination usually fall into one of three broad categories: tastes and preferences of economic agents, economic power, and statistical discrimination. Unlike the world of theory, empirical documentation of discrimination is subject to much ambiguity and differences of interpretation.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

2. Theories Of Discrimination

2.1 Tastes And Preferences

Publication of The Economics of Discrimination (1957) by Gary Becker was instrumental in making discrimination a legitimate and popular topic for study by economists. The tastes and preferences approach adopted by Becker was pure neoclassical economics. This approach appeals to tastes for discrimination by utility-maximizing economic agents. Tastes for discrimination are embodied in discrimination coefficients that are susceptible to measurement by the economist’s monetary yardstick. Agents’ tastes for discrimination are manifested by a desire to minimize economic transactions with members of certain demographic groups. While discriminating agents may be prepared to forfeit income in order to indulge their tastes, the effects of their discriminatory behavior can lead to segregation or reduced incomes for the groups discriminated against. In addition to employer tastes for discrimination, Becker also considered the effects of tastes for discrimination by consumers and fellow workers. Under some circumstances, competitive pressures can ameliorate the effects of discriminatory behavior.

The literature provides support for Becker’s contention that labor-market discrimination is lessened by product market competition. Ashenfelter and Hannan (1986) present statistical evidence that within the banking sector the employment opportunities for women are negatively related to market concentration. Peoples and Saunders (1993) show that deregulation of trucking in the USA lowered the white black wage ratios among both union and nonunion drivers. This competitive effect was identified with the reduction of rents accruing to whites.

One avenue for exploring the effects of discrimination by fellow workers is to examine the effects of unionism on racial wage differentials. An early study by Ashenfelter (1972) showed that the average wage of black workers relative to the average wage of white workers in the USA was higher in the union sector than in the nonunion sector. In particular, Ashenfelter estimated that compared with the complete absence of unionism, the black white wage ratio was 4.0 percent higher in the industrial union sector, and 5.0 percent lower in the craft union sector. These results suggest that the union sector is less discriminatory than the nonunion sector, and that industrial unions are relatively more egalitarian compared with craft unions. Peoples (1994) found evidence not only that the returns to union membership are higher for blacks than for whites, but also that racial wage differentials were higher among nonunion workers in the highly concentrated industries.

2.2 Market Power

Prior to Becker, early work by economists on the topic of discrimination focused on pay differentials between men and women. Joan Robinson’s (1933) classic on imperfect competition provided an early example of the economic power theory of discrimination. Robinson considered the case of a monopsonistic employer (single employer labor market) of men and women who are equally productive (perfect substitutes in production). She proved that if the labor supply elasticity (responsiveness to wages) were smaller for women, a profit-maximizing employer would equate the incremental employment costs of men and women by offering women a lower wage.

Madden (1975) explored the circumstances under which the labor-supply elasticities of women would be lower, and how male monopoly power insulates men from any monoposony power that might exist in labor markets. The key element was the existence of job segregation which reduced competition from women. It was shown that under these circumstances women would receive lower wages than men, if both worked in equally productive, but different, sets of jobs. Earlier, Bergmann (1971) advanced the occupational crowding hypothesis to explain income inequality between white male workers and otherwise equally capable nonwhite workers. Crowding nonwhites and women into a narrower range of occupations raises the incremental value of white males in their occupations and lowers the incremental value of all workers in the occupations dominated by nonwhites and women.

The ubiquity and self-reinforcement of a broad range of discriminatory behavior in society was examined in Thurow (1969). For example, discrimination in schooling opportunities has the effect of diminishing the subsequent earnings potential of minority workers. This reduces the costs to discriminating employers of paying lower wages to minority workers, as the latter will have fewer skills to begin with. Lower wages reduce the cost of housing discrimination because better housing is beyond the incomes of most minority workers.

2.3 Statistical Discrimination

Statistical discrimination is an approach that relies upon risk and information costs rather than tastes for discrimination or market power to explain income disparities among different demographic groups in society (Aigner and Cain 1977). One example is that of two groups who are equally productive on average, but the productivity signal, for example, test scores, is a noisier signal of productivity for one of the groups. A risk-averse, profit-maximizing employer might offer lower wages or less desirable positions to applicants from the demographic group with the noisier signal. Consequently, employment decisions are made on the basis of group characteristics as well as on the basis of individual characteristics.

3. Wage Decompositions

In the study of wage inequality, the most commonly used methodology for apportioning wage gaps between two demographic groups to productivity and discrimination can be traced to Blinder (1973) and Oaxaca (1973). The basic idea is quite simple. One first estimates wage equations for each of the demographic groups from a sample of workers. These wage equations are mathematical formulas relating wages to observed productivity factors such as education and experience. In the absence of direct labor-market discrimination, equity is characterized as a situation in which both demographic groups are expected to be compensated according to the same wage (salary)determination formula. In this scenario the only reason for the existence of a wage gap would be that the two groups differ on average with respect to the observed wage (productivity)-determining characteristics. This wage gap is commonly referred to as the ‘endowment’ or human capital effect.

The difference between the actual wage gap and the endowment effect is often referred to as the ‘un- explained gap.’ Many practitioners regard the un- explained gap as an estimate of discrimination. Those who prefer the term ‘unexplained gap’ reason that this estimate is in the nature of a residual and as such may include the effects of productivity factors not explicitly taken into account in the wage-determination formula. Hence, the measure may be a biased estimate of discrimination. From an econometric standpoint, the bias can go in either direction. The counterargument is that there are always factors omitted from any statistical relationship and that there is no reason to suppose that these are anything but random in the present context. In addition, the same sort of methodology is very commonly used to estimate other types of wage gaps, for example union nonunion, north south, manufacturing nonmanufacturing. In these contexts the term ‘unexplained gap’ is not used.

According to the Blinder Oaxaca standard decomposition methodology, one of the two demo- graphic comparison groups is designated as the reference group. If, for example, one is interested in male female wage differentials, one might select males as the reference group. This means that the statistically estimated wage formula for males serves as the nondiscriminatory wage structure. Operationally, one estimates the average wages for both males and females by applying the estimated male wage formulation to each group’s wage-determining characteristics. The gender difference in these predicted average wages is the ‘endowment’ effect, since the same wage formula is applied to the characteristics of both groups. The difference between the original unadjusted wage gap and the gap attributable to the ‘endowment’ effect is by definition the result of different wage formulas for males and females. This residual gap is what is termed either the ‘unexplained gap’ or the gap attributable to direct labor-market discrimination. Therefore, the decomposition technique is a method for decomposing an observed wage gap into an endowment component and an unexplained discriminatory component.

3.1 Identification Of Individual Components Of Discrimination

Apart from differences in what researchers call the ‘residual gap,’ there are other ambiguities in the standard decomposition technique. First, it would seem desirable to be able to identify the contribution of each wage-determination characteristic to the endowment component and the discrimination component. For example, one could identify the contribution of gender differences in a characteristic such as work experience to the overall endowment effect as the gender difference in average work experience multiplied by the pecuniary return to an additional unit of work experience estimated from the male wage equation. Or consider the case of a wage-determining characteristic defined by a set of mutually exclusive categories such as educational levels, for example, ‘less than high school,’ ‘high school,’ ‘some college,’ and ‘college graduate.’ The estimated return to each included educational category is relative to the return on an arbitrarily selected educational category variable that is omitted from the wage equation. The monetary value of gender differences in the proportion of workers in the sample who are college graduates is simply calculated as the gender difference in the proportion of college graduates weighted by the estimated value of a college education for males relative to the omitted educational category. The sum of all of these endowment valuations equals the overall endowment effect.

Unfortunately, an identification problem can arise when one attempts to estimate the contribution of each wage-determination characteristic to the dis- crimination component. The problem is initially de- scribed in Jones (1983) and further extended in Oaxaca and Ransom (1999). For example, weighting the average amount of work experience for females by the male–female difference in the estimated return to an additional unit of work experience would constitute a measure of the contribution of gender differences in the return to experience to the overall discrimination measure. It turns out that this computation is affected by a simple shift in the experience measure. For example, potential experience is commonly calculated as either schooling-age-five or schooling-age-six. This is a seemingly innocuous shift in the experience measure, yet it will affect the estimated contribution to discrimination of gender differences in the return to experience. Because this change in the experience measure creates an offsetting change in the intercept term in the wage equations for males and females, it does not affect the overall estimate of discrimination. Nor does this change in the experience measure have any effect on the contribution of gender differences in work experience to the endowment effect.

This arbitrariness is more manifest when attempting to estimate the contribution to discrimination of gender differences in the returns to a variable defined by mutually exclusive categories. Returning to the education example, note that the contribution to measured discrimination of the gender difference in the returns to education is calculated as the sum of the gender differences in the estimated returns for each included educational category weighted by the proportion of females who are in each included category. As it turns out, this calculation is affected by the choice of which educational category variable is to play the role of the omitted reference category. The choice of omitted reference category is of course quite arbitrary. Fortunately, the overall estimated discrimination component is not affected by which categorical variables are selected to be the omitted reference categories. Also, the choice of omitted reference group has no effect on the estimated contribution to the endowment effect of gender differences in the values of the categorical variables.

3.2 Nondiscriminatory Wage Structures

To examine a second source of ambiguity in standard wage decompositions, imagine that the choice of reference group is reversed so that female workers are designated as the reference group. Now one estimates the (nondiscriminatory) average wages for both males and females by applying the estimated female wage formulation to each group’s wage-determining characteristics. An ambiguity arises in that in general estimates of the endowment and discriminatory wage effects will depend on which demographic group is serving as the reference group. This ambiguity is a manifestation of the familiar index number problem. The researcher is trying to measure ‘value’ using alternative base weights.

As a measure of discrimination, the estimated residual gap is subject to quite different interpretations depending on the choice of reference group. The situation is one in which the presence of discrimination is manifested as a wage gap based on the fact that in actuality men and women do not face the same wage-determination process. This can be viewed as either that women are underpaid relative to the male wage structure or else that men are overpaid relative to the female wage structure. The interpretation and estimated magnitude of each of the two components comprising the original unadjusted wage gap depend on which group’s wage structure is regarded as the nondiscriminatory standard. To further add to the ambiguity surrounding wage-decomposition analysis, there is the theoretical possibility that which group is being discriminated against depends on whose wage-determination formula is being used as the nondiscriminatory standard.

It is clear that the second type of ambiguity surrounding the standard wage decomposition analysis has to do with identifying an appropriate nondiscriminatory wage standard. Ideally, one would want the wage structure that would prevail in a nondiscriminatory world to serve as the standard by which to measure actual discrimination. Under some assumptions, such a wage structure would be the one that would exist in a world characterized by perfect competition in product markets and labor markets. One would estimate the average wages for both males and females by applying the nondiscriminatory wage formulation to each group’s wage-determining characteristics. The gender difference in these predicted average wages is the endowment effect. Again, discrimination is measured by the unadjusted gender wage gap net of the endowment effect. However, it is now possible to further decompose the discriminatory wage gap because the gap is in general the sum of two distinct components. The first component is the difference between the actual average wage of the male workers, and their predicted average wage based on the nondiscriminatory structure. The second component is the difference between the predicted average wage of females based on the nondiscriminatory wage structure, and their actual average wage.

These discriminatory wage components have interesting interpretations (Neumark 1988). The first component is a measure of the male wage advantage relative to the nondiscriminatory norm. This component can be viewed as favoritism toward males. The second component is a measure of the female wage disadvantage relative to the nondiscriminatory norm. This component can be viewed as pure discrimination against female workers. This methodology, in principle, allows researchers to sort out how much of the male–female discriminatory wage gap results from overcompensation of men, and how much stems from undercompensation of women. In the light of this approach, the conventional decomposition method is seen as a special case.

While seemingly attractive as a decomposition method, there is a practical difficulty in making operational the concept of a nondiscriminatory wage structure. One notion is the wage structure that would prevail had discrimination never existed. A slightly less challenging task might be to define the non-discriminatory wage structure as the structure that would emerge in the immediate aftermath of a cessation of discrimination. In general, this is not the same as the wage structure that would have prevailed had discrimination never existed. This is because of a likely path-dependence feature in which discrimination permanently alters the evolution of wage structures. While a still formidable enterprise, it is possible to reach useful approximations to a wage structure that would emerge after the cessation of discrimination.

The basic idea underlying this approach is contained in Neumark (1988) and Oaxaca and Ransom (1999). A reasonable presumption is that with the cessation of discrimination between two demographic groups, the resulting wage structure would in some way be related to the preexisting separate wage structures. A natural approximation is the wage structure that is estimated on the basis of a combined sample obtained by pooling the data on the two demographic groups. Such a common wage structure can be shown to be a matrix-weighted average of the separately estimated wage structures. The weights are related to the precision by which each group’s wage-equation parameters are statistically estimated. Neumark (1988) applies this methodology to the gender wage gap.

In Oaxaca and Ransom (1994) the methodology is generalized to allow for estimation of a nondiscriminatory wage structure as any matrix-weighted average of the separately estimated wage structures. Without restrictions on the weighting matrices, any common wage structure can be rationalized as a matrix-weighted average of the separately estimated wage structures. Reimers (1983) uses simple averages of separately estimated wage structures when comparing whites, blacks, and Hispanics.

3.3 Residual Decomposition

An important aspect of the study of wage inequality is trying to understand the components of changes or trends in wage inequality. Juhn et al. (1991) introduce a method of decomposing changes in the residual wage gap between two demographic groups into the effects of changes in the average rankings of the two groups in the residual wage distribution of the dominant group, and the effects of changes in the residual wage dispersion (standard deviation) of the dominant group. This approach is referred to as the Juhn– Murphy–Pierce (JMP) decomposition. It follows the practice of interpreting the wage gap left after controlling for group differences in observed characteristics as an unexplained differential.

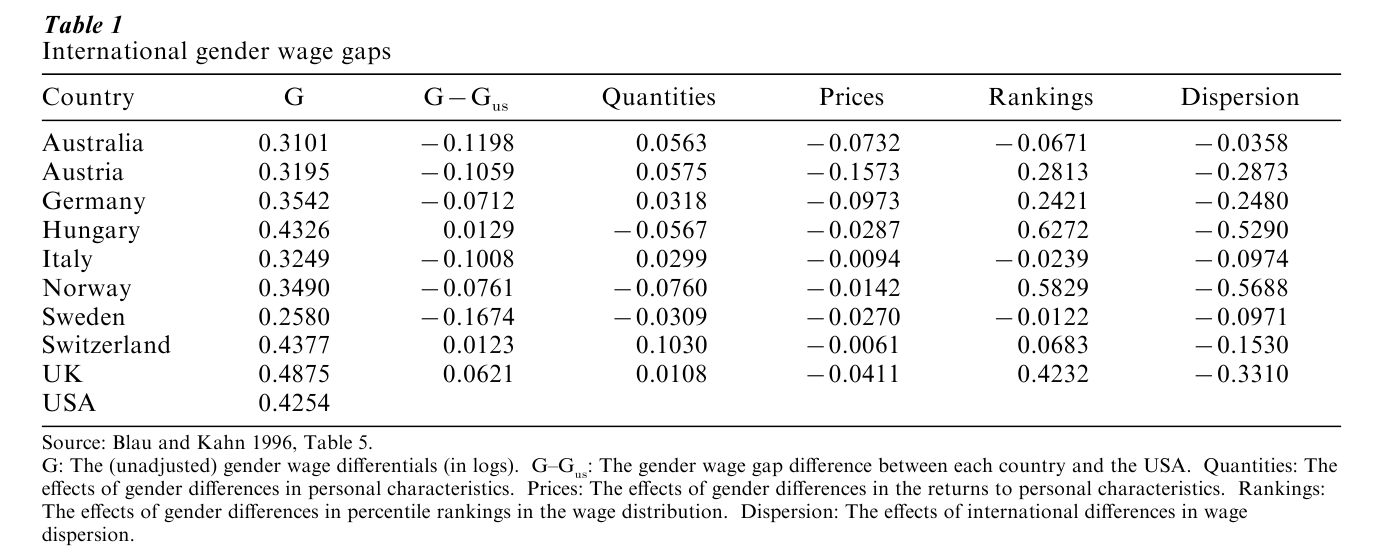

In Blau and Kahn (1996) the JMP decomposition is adapted to analyzing gender wage gap differences between nine countries and the USA during the 1980s. Earnings are standardized to a full-time (40 hours) work schedule. The earnings models estimated with microdata sets control for education, potential experience, union membership, industry, and occupation. Table 1 summarizes the Blau and Kahn findings in which the gender wage gaps in each country are compared with that of the USA. Column 2 reports the raw (log) wage differentials by country. The wage gaps range from 0.258 log points (approximately 26 percent) in Sweden to 0.4875 log points (approximately 49 percent) in the UK. Column 3 reports each country’s wage gap minus that of the USA. It is this difference that is decomposed into the effects of international differences in the following: (a) gender differences in human capital characteristics (quantities); (b) the (male) returns to human capital characteristics (prices); (c) gender differences in the percentile rankings in the male wage residual distribution (rankings); and (d) differences in the (male) standard deviation of the wage residuals (dispersion). In six of the nine countries, the male human capital advantage is greater than that of the USA. Without exception, international differences in the returns to human capital and in the dispersion of wage residuals lower the gender wage gap in other countries relative to the USA. In six of the nine countries the less favorable rankings of women in the male wage residual distribution widens the gender wage gap relative to the USA. What emerges from this study is that the gender wage gap is relatively high in the USA because the greater wage residual inequality in the USA more than offsets the greater relative human capital of US women.

4. Correcting Wage Inequities

Although economists are presumably interested in measuring the extent to which discriminatory wage gaps represent overpayment of the dominant group versus underpayment of the subordinate group, custom and the legal environment lean more to the dominant group’s wage structure as the nondiscriminatory standard. The idea is that inequities should be addressed by raising the wages of the subordinate group, as opposed to lowering the wages of the dominant group. Indeed, the US Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits equity wage adjustments that involve lowering any group’s nominal wages. Thus, attempts to remove discrimination in the workplace in a way that would correspond to accepted economic principles of efficiency are constrained by legal and employee morale considerations.

4.1 Econometric Modeling Approaches

One might properly speculate about how econometric models of the wage-determination process can be used to address a salary inequity issue in the workplace. Examples from legal practice are provided in Finkelstein (1980). Oaxaca and Ransom (1999) report on several approaches on how to use statistical salary models to correct salary inequity within a firm. For illustrative purposes, the examples are in terms of gender inequity, but the methodology extends without modification to racial or ethnic salary inequity. The remedies range from simply compensating each female worker exactly according to the estimated male wage equation to constraining the salary equity adjustment process to award minimum settlements regardless of personal circumstances.

4.2 Comparable Worth

Comparable worth is a general policy for eradicating discriminatory wage disparities within firms. The idea behind comparable worth is that jobs of equal value should pay equal wages. While this sounds like free market economics, at issue is how value is determined (Hill and Killingsworth 1989). Advocates of comparable worth envision a system in which points are awarded to each job based on the skills, effort, and responsibility required. Experts are responsible for evaluating a firm’s jobs in a manner that does not bias wage determination against women. The objection against letting the market value the jobs is that occupational segregation dooms women to a subordinate wage position. An important question is whether or not comparable worth would provide employers with the incentives to eliminate job segregation, and whether or not women would switch among occupations that were equally compensated. Critics of comparable worth fear the massive inefficiencies that could emerge from interference with labor-market resource allocation.

5. Self-Selection In The Labor Force

Estimation of labor-market discrimination in general is complicated by the observation that individual workers in a statistical sample generally do not constitute a random sample of the adult population. Whether or not to participate in the labor force will depend upon the individual’s calculation of the net benefits of labor-force participation. While the net benefits are unobserved by researchers, the decision to participate is observed, as well as many determinants of the net benefits. For women, the presence of small children at home would likely be a factor in the decision to be in the labor market. The statistical equation corresponding to labor-force participation is known as a selection equation, since it describes a rule for individuals to select themselves in or out of the labor force.

Sample selection bias can arise when the random statistical errors in the selection equation are correlated with the random statistical errors in the wage equation that is being estimated for a self-selected sample of workers (Heckman 1979). Unless the probability of selection (which depends on the selection equation) is taken into account, the estimated parameters of the wage equation can be biased. The selection probabilities for the selected sample are controlled for in a variable known as the Inverse Mills Ratio. This variable is constructed from the variables and parameters of the selection equation.

A number of studies have attempted to correct for sample selection bias when dealing with occupational segregation or more generally labor-market discrimination (Reimers 1983, Dolton et al. 1989, Neuman and Oaxaca 1998). Neuman and Oaxaca (1998) explore alternative ways of estimating (ethnic and gender) labor-market discrimination from selectivity- corrected wage equations using a sample of Jewish professional workers drawn from the Israeli 1983 Census of Population and Housing.

6. Progress And Future Directions

Smith and Welch (1989) chronicle the economic progress of African-Americans over a 40-year period. Black male wages as a percent of the white male wage rose from 43.3 percent in 1940 to 72.6 percent by 1980. The documented wage gains of African-Americans were largely attributed to more and better education, migration, and general economic growth. Some evidence was found that affirmative action policies improved the employment and wage prospects of African-Americans. Data from the US Current Population Survey are consistent with the Smith and Welch findings. The median income of full-time, year-round black workers as a percent of the median income of full-time, year-round white workers rose from 68.1 percent in 1970 to 73.9 percent in 1998.

Empirical findings from gender labor-market studies are quite mixed, variable over time and across countries. Zabalza and Tzannatos (1985) examine the gender employment and wage effects of labor-market legislation in the UK on the employment and wages of women. Panel data, which contain detailed information on individuals over their working lives, have been used to study gender wage gaps in Denmark (Rosholm and Smith 1996). In a shift of emphasis from gender wage discrimination Fluckiger and Silber (1999) examine both theoretically and empirically the phenomenon of gender labor market segregation with special emphasis on the Swiss labor market.

Empirical studies of racial-, ethnic-, gender-, and caste-based labor-market outcomes in developing countries may also be found (Birdsall and Sabot 1991, Psacharopolulos and Patrinos 1994). Intercountry comparisons of labor-market inequity between the developed and the developing countries will be the inevitable result of globalization. The implications of labor-market discrimination for international trade and specialization should occupy the attention of social scientists well into the twenty-first century.

Bibliography:

- Aigner D, Cain G 1977 Statistical theories of discrimination in the labor market. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 30: 175–87

- Ashenfelter O 1972 Racial discrimination and trade unionism. Journal of Political Economy 80: 435–64

- Ashenfelter O, Hannan T 1986 Sex discrimination and product market competition: The case of the banking industry. Quarterly Journal of Economics 101: 149–4

- Becker G 1957 The Economics of Discrimination. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Bergmann B 1971 The effect on white incomes of discrimination in employment. Journal of Political Economy 79: 294–313

- Birdsall N, Sabot R (eds.) 1991 Unfair Advantage: Labor Market Discrimination in De eloping Countries. The World Bank, Washington, DC

- Blau F D, Kahn L M 1996 Wage structure and gender earnings differentials: An international comparison. Economica 63(Suppl.): 29–62

- Blinder A S 1973 Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. Journal of Human Resources 8: 436–55

- Dolton P J, Makepeace G H, Van der Klaauw W 1989 Occupational choice and earnings determination: The role of sample selection and non-pecuniary factors. Oxford Economic Papers 41: 573–94

- Finkelstein M 1980 The judicial reception of multiple regression studies in race and sex discrimination cases. Columbia Law Review 80: 737–54

- Fluckiger Y, Silber J 1999 The Measurement of Segregation in the Labor Force. Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany

- Heckman J 1979 Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47: 153–61

- Hill M A, Killingsworth M R (eds.) 1989 Comparable Worth: Analyses and Evidence. Industrial Labor Relations Press, Ithaca, NY

- Jones F L 1983 On decomposing the wage gap: A critical comment on Blinder’s method. Journal of Human Resources 18: 126–30

- Juhn C, Murphy K M, Pierce B 1991 Accounting for the slowdown in black-white wage convergence. In: Kosters M H (ed.) Workers and their Wages. AEI Press, Washington, DC, pp. 107–43

- Madden J F 1975 Discrimination—A manifestation of male market power? In: Lloyd C B (ed.) Sex, Discrimination, and the Division of Labor. Columbia University Press, New York, Chap. 6, pp. 146–74

- Neuman S, Oaxaca R L 1998 Estimating Labor Market Discrimination with Selectivity Corrected Wage Equations: Methodological Considerations and An Illustration From Israel. Centre for Economic Policy Research, London

- Neumark D 1988 Employers’ discriminatory behavior and the estimation of wage discrimination. Journal of Human Resources 23: 279–95

- Oaxaca R L 1973 Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review 14: 693–709

- Oaxaca R L, Ransom M 1994 On discrimination and the decomposition of wage diff Journal of Econometrics 61: 5–21

- Oaxaca R L, Ransom M 1999 Using econometric models for intrafirm equity salary adjustments. Unpublished paper, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ and Brigham Young University, Provo, UT

- Peoples J 1994 Monopolistic market structure, unionization, and racial wage diff Review of Economics and Statistics 76: 207–11

- Peoples J, Saunders L 1993 Trucking deregulation and the black white wage gap. Industrial & Labor Relations Review 47: 23–35

- Psacharopolulos G, Patrinos H (eds.) 1994 Indigenous People and Poverty in Latin America: An Empirical Analysis. The World Bank, Washington, DC

- Reimers C 1983 Labor market discrimination against Hispanic and black men. The Review of Economics and Statistics 65: 570–9

- Robinson J 1933 The Economics of Imperfect Competition. Macmillan, London

- Rosholm M, Smith N 1996 The Danish gender wage gap in the 1980s: A panel data study. Oxford Economic Papers 48: 254–79

- Smith J P, Welch F 1989 Black economic progress after Myrdal. Journal of Economic Literature 27: 519–64

- Thurow L 1969 Poverty and Discrimination. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

- Zabalza A, Tzannatos Z 1985 Women and Equal Pay: The Effects of Legislation on Female Employment and Wages in Britain. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK