Sample Eastern European Economics Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The changes in the Eastern European economies during the first decade of the transition to capitalism have been, without exaggeration, momentous. Beginning in the late 1980s, the countries in the region emerged from a system based on communist party rule, state ownership, and central planning, and adopted in its place a system based on multiparty democracy, private ownership, and markets. Although the break with the past was radical, and notwithstanding that the region is poised for period of rapidly improving living standards, the first decade of transition was difficult. Most countries suffered deep recessions, experienced massive redistributions of in-come and wealth, and struggled with the slow process of building supporting institutions for a market economy. And even for the countries that have advanced furthest, the transition is not over. The next decade will bring further momentous changes as countries prepare for accession to the European Union.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Transition has been a challenge for economists. Never before had industrial countries attempted to adopt abruptly the institutions of capitalism. New tools had to be developed to understand such phenomena as transitional recession, mass privatization, and the political economy of institutional reform. Transition has also provided a great opportunity to understand the role of the many background institutions of capitalism. By observing the long list of institutions that had to be put in place, and by observing how economies performed when these institutions were lacking, the economics profession has attained a deeper understanding of how even established market economies work.

1. Initial Conditions

By the end of the 1980s, a number of communist countries, including the Soviet Union, had gone through a period of reform socialism (Kornai 1992). Among other changes, these reforms allowed greater autonomy for state enterprises, permitted some small-scale private enterprise, and increased the use of prices in allocating economic resources. However, these reforms did not alter the one-party rule and a preponderance of state ownership that were the foundation of the communist system. So the pathologies of the classical socialist system remained (Kornai 1992). Resources were allocated according to the dictates of central planners rather than household needs. Production methods were inefficient. And lacking the long-term profitability constraint faced by enterprises on market economies, socialist enterprises with soft budget constraints retained insatiable demands for inputs. Together with the continuing reliance on price controls, these demands made shortages pervasive.

Reform socialism led, in fact, to a slackening of the financial discipline on enterprises. And this in turn led to an increase in macroeconomic imbalances. At prevailing prices, the aggregate demand for goods and services exceeded the supply. In the years prior to the transition, communist governments dealt with these imbalances in three ways. They engaged in large foreign borrowing to increase the availability of goods and services; they repressed the inflationary pressures with price controls and rationing of the available goods; and they allowed open inflation.

At the outset of transition, then, reforming governments inherited economies with combinations of large debts, long queues, and high inflation rates (Lipton and Sachs 1990). They also inherited a distorted industrial structure, most notably an over-reliance on heavy industry, and a badly developed service economy. From a longer-term perspective, perhaps the most adverse part of the inheritance of all was the absence of key marketing supporting institutions, such as an established code of commercial law or a supervisory apparatus for market-oriented financial institutions. With this mix of macroeconomic imbalances and microeconomic deficiencies, the path to a market economy must have appeared daunting to the first postcommunist governments.

2. Transition

It is common to put the main steps in postcommunist transition under three rather ugly headings: liberalization, stabilization, and privatization. Much of the subsequent work the economics of transition has concentrated on these processes.

2.1 Liberalization

The first, and arguably the easiest, steps in the transition are the removal of most government controls (see Sachs 1993 for an account of the Polish experience). For example, the government simply stops controlling prices, allowing them to jump to their market levels, or ends prohibitions on new private businesses. In a related step, the government decentralizes decision-making authority to enterprises, in effect dismantling the central planning apparatus.

On the external front, the government moves to allow for freer trade and factor movements. Complicated permission requirements for exporting, high tariff and nontariff barriers to imports, and severe restrictions on foreign ownership are relaxed. In addition to gaining access to foreign markets, goods, and capital, opening up the economy to the rest of the world increases competition and exposes the population to best practice in technology and organization.

2.2 Stabilization

As noted before, postcommunist governments inherit severe macroeconomic imbalances. Even with price controls, the inflation rate typically is already high prior to the transition. Price liberalization is associated with an upward jump in prices as they reach market-clearing levels, ending the previous situation of chronic excess demand. These jumps can also have a longer-lasting impact on inflation to the extent that they cause expectations of higher future inflation.

The most important cause of the high inflation, however, is the underlying growth in the money supply. This has two main sources. First, there is the government’s budget deficit. Under communism, governments relied heavily on taxes on enterprise turnover to fund their spending. They also delegated much of the responsibility for social spending directly to the enterprises. Transition has been associated with a fall in revenues and increased spending demands on governments. For many countries, the result has been large budget deficits that are financed in part by printing money. Second, there is the financing of enterprise losses. Although the enterprises attain much greater autonomy, budget constraints remain soft. In other words, their losses are bailed out through support from the government or (more likely) ‘soft’ loans from the (government-controlled) banking system. In turn, the banks’ losses are bailed out by ‘soft’ support from the central bank, which they finance by printing money.

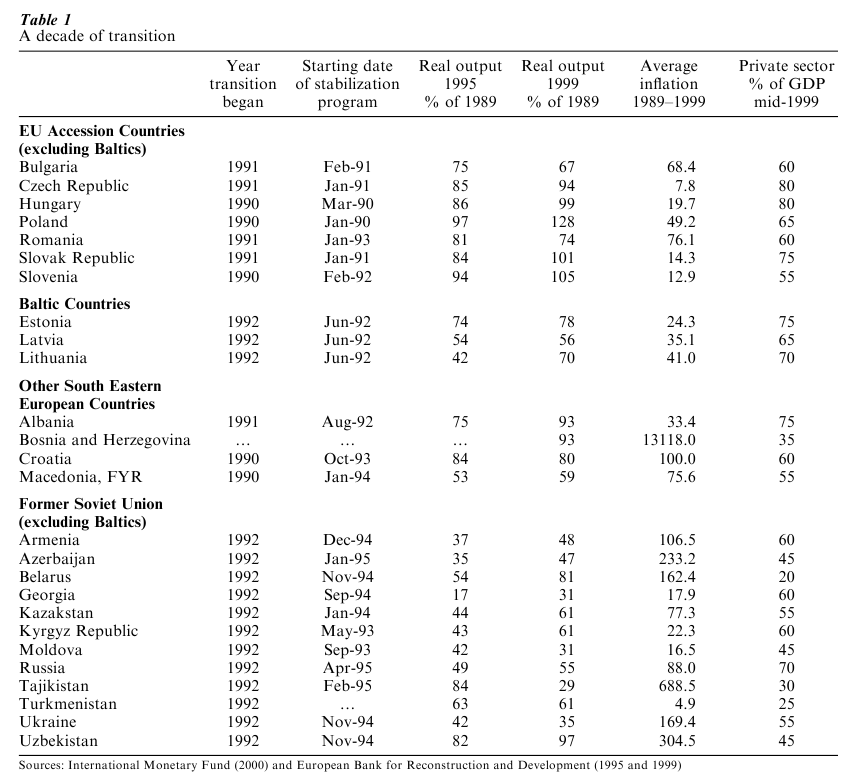

Since a stable price level is an essential feature of a market economy, one of the most urgent tasks for the post-communist government is to bring down inflation toward single-digit levels. Table 1 provides dates for the beginning of major stabilization efforts in various countries. Given the underlying sources of money supply growth, true stabilization requires reducing the size of the government’s budget deficit (or at least reducing reliance on monetary financing of those deficits), and the ability to impose hard budget constraints on enterprises. Each step is difficult as it imposes additional hardships on the population. Thus, for many countries, stabilization has been a slow and indeed a continuing process. As Table 1 shows, average inflation rates for the decade of the 1990s were high by established market economy standards.

For economists, the nature of the post-communist stabilization challenge was not especially novel. The nature and causes of high (and even hyper) inflation were well known, with the most recent experience being the hyperinflation episodes in Latin America following the debt crises of the 1980s. Some of the challenges were more novel, including the massive and often sudden decontrol of prices, and the mass introduction of new currencies in the countries of the former Soviet Union. By and large, however, economists were able to use their accumulated wisdom on such matters as the importance of ending the printing of money to finance budget deficits, and the usefulness of exchange rate pegs to anchor inflationary expectations in the early stages of a stabilization program. (For an overview of research on postcommunist inflation and the stabilization experience, see Boone and Horder 1998.)

2.3 Privatization

In theory it is possible to have a successful market economy while retaining extensive state ownership. In practice, state ownership is associated with the politicization of enterprise decision-making (Shleifer and Vishny 1994). It is easier for politicians to control firms when the state is the owner. Moreover, politicians will use their control to pursue political ends—say, preserving jobs for constituents—rather than to maximize profits. Thus continued state ownership is an impediment to restructuring enterprises and reallocating resources. Political control is also associated with soft budget constraints, as politicians are willing and able to bail out the losses incurred while pursing their political objectives. Success with stabilization can thus depend on success with privatization.

There are a number of methods for achieving privatization: Sales to the highest bidder; restitution to pre-communist owners; voucher privatization; manager–worker buyouts, etc. Whatever the method, it might be thought that privatization is easy politically. After all, the government is transferring assets to the private sector, potentially at a large discount. In practice, groups seeing themselves as losing from privatization, or not gaining as much from the transfer of assets as they could, often have the power to block an unfavorable privatization proposal. For example, the management of state enterprises might thwart attempts to sell the enterprise to outside owners. Where such blocking power exists, the blocking groups may have to be bought out by the government, possibly by buying access to shares at steeply discounted prices.

A good example of such ‘buy-offs’ is the early stage of Russian privatization. Then, enterprise insiders— managers and workers—received excellent deals on their companies’ shares. While this allowed privatization to proceed, and helped to depoliticize enterprise control, it might have led to excessive insider control (see Boycko et al. 1994). When insiders control a firm, they are likely to use their power to achieve objectives that run counter to efficiency, such as prolonging overstaffing. As outsiders recognize insider power to appropriate the valued added of the enterprise, high insider control makes it difficult to raise outside finance, and thus acts as an obstacle to restructuring and new investment (see Blanchard 1997). Moreover, preferential privatization has led to quite unequal distributions of previously state-owned assets, a topic returned to in Sect. 3.2 below.

The theoretical literature has concentrated on the political economy of mass privatization as well as the various channels for efficiency gains when shifting from state to private ownership (see Roland 2000, for a survey.) There is an even larger empirical literature the records the privatization strategies pursued and investigates the impact of the resulting ownership forms on restructuring behavior. Although this literature does not speak with one voice, the balance of evidence suggests that ownership by enterprise outsiders with large ownership stakes leads to most restructuring (for a flavor of the results and the empirical methods used, see the papers by Estrin 1998 and Frydman et al. 1999).

3. The Transition Experience: Pain And Progress

3.1 Transitional Recession

All the transition economies experienced severe and, for many, long-lasting recessions (Layard 1998). Table 1 shows the level of real GDP in both 1995 and 1999, each as a percentage of output in 1989. The table makes for grim reading. In 1995 all countries had measured real output levels that were below levels achieved in 1989. The picture had brightened by 1999, with Poland, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia surpassing their 1989 output levels, and a number of other countries approaching this benchmark. In the countries of the former Soviet Union, however, the picture remained bleak. In Russia, for example, real output in 1999 was just 55 percent of the 1989 level.

These real output statistics almost certainly overstate the true output contractions. Much of the lost output had little value—and perhaps even negative value—as valuable raw materials were destroyed in irrational production processes. Nonetheless, the recessions were real, with sharp reductions in employment and expansions of unemployment.

Why did the transition economies suffer these transitional recessions? After all, if the communist system was so inefficient, should we not expect that real output would increase as countries adopt market systems? The early hope of experts on communist systems was that the postcommunist economies would move from a situation of generalized excess demand (or shortage) to macroeconomic balance, without tipping into a situation of generalized excess supply (Kornai 1995). Various explanations for the sharp contractions have been given in the literature. Early explanations focused on the impact of the sharp post liberalization price jumps, and on Keynesian type explanations of insufficient demand. The sharp jump in prices was thought to have limited real working capital severely, forcing enterprises to cut their production (see, e.g., Calvo and Coricelli 1992). On the demand side, a general lack of consumer and investor confidence, combined with tight government fiscal and monetary policies, was initially thought to be responsible for pushing real output below the economy’s potential to produce. As time passed, and the transition economies failed to recover, or recovered very slowly, these explanations were revised. Economists began to look for more systemic explanations. One important explanation focused on the ‘disorganization’ that results in the no-man’s-land between systems (Blanchard and Kremer 1997, Roland and Verider 1999). For a time after a central planning apparatus has been destroyed, but before market coordination is properly established, the ability to coordinate economic activity is severely impaired. Supply disturbances in one part of the economic system tend to cascade through the economic system, impairing severely the economy’s potential to produce.

A related explanation focuses on the inherent unemployment bias present in market systems. When unemployment falls below the natural (or structural) rate of unemployment, inflation tends to rise. Thus, stable inflation is only consistent with what can be a relatively high rate of unemployment. (That this structural unemployment rate can be quite high is demonstrated by the high rates of unemployment in many Western European economies, even in the expansion phases of their business cycles.) In contrast, under communism, unemployment was negligible, and inflation was controlled by fiat. As an economy goes through a postcommunist transition it can no longer sustain its previously high rate of activity without suffering accelerating inflation. Over time it is expected that the superior efficiency of market coordination will lead to superior output performance, but in the short-run the loss of ability to run a high-pressure economy dominates, and output falls.

Lastly, a number of authors have stressed the impact of the large reallocations that must take place during the transition (see, e.g., Gomulka 1998). Some enterprises, and even entire industries, decline rapidly as there is little demand for their products in the newly liberalized economy. The result is a large but temporary decline in output as it takes time for the displaced resources to find productive employment in expanding sectors.

3.2 Large Redistributions Of Income And Wealth

Transition is associated with substantial changes in household incomes and balance sheets. Factors affecting the income relativities include the large rise in unemployment and falls in (especially female) participation, the shift in resources from heavy industry to lighter industry and services, and hardships faced by older workers with specific skills in adjusting to the new pattern of labor demands.

In addition to the large income gains and losses for particular households, there has also been a large increase in overall income inequality. For the mid- 1990s, Milanovic (1998) reports substantial increases in inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient for income per capita compared with the late 1980s, with particularly large increases for the countries of the former Soviet Union. The Gini coefficient for Russia increased to a staggering 48 in the period 1993–5 from 24 in the period 1987–8. This compares with much smaller increases for more advanced reformers, with the Gini rising to 28 from 26 for Poland, and to 23 from 21 for Hungary for the same periods.

There have also been very large shifts in wealth distribution (although reliable numbers are hard to come by). Under communism, price controls and generalized shortages forced people to accumulate undesired liquid wealth holdings, creating a monetary overhang of latent spending power. With price liberalization, people were able to spend down these undesired balances, contributing to the large price jump. However, this price jump also reduced the purchasing power of all (nonindexed) nominal wealth, causing substantial but unequal wealth losses.

Privatization has also affected wealth distribution, although given the low value of much of the communist-era capital stock, the amount of wealth available for distribution should not be exaggerated. The distributional impact of privatization depends on the privatization method pursued. At one extreme, sales at reasonably fair prices (as in Hungary) should have rather minor impacts on wealth inequality, while at the other, extreme giveaways to the politically wellconnected of valuable energy-sector assets (as in the second wave of privatization in Russia) must have had a major impact.

If we take a broader view of wealth to include the value of assets such as entitlements to pensions and job incumbency, the impact of transition on wealth distribution has obviously been great.

3.3 Supporting Institutions For Capitalism

For economists and political scientists, one of the unanticipated benefits of the transition experience is that it has given us a deeper understanding of the role of institutions in the capitalist system, and the difficulties involved in their establishment (Roland 2000). An incomplete list of the institutions that facilitate economic activity in a private ownership economy includes the following: Regulatory and supervisory authorities for financial intermediaries and securities markets; company laws that protect the interests of outside shareholders; a body of contract law that facilitates long-term contracting; an independent judiciary; etc.

Reformist governments can liberalize and stabilize relatively quickly, and even privatization can be well advanced in a few years with the necessary will. Institutional development takes more time. The Czech government provides a good example of a country that pushed ahead quickly with price decontrol, disinflation, and sales of state assets, but the inadequacies of its background institutions were shown in a series of scandals related to insider dealing (see LaPorta et al. 2000). These failures undermined investor confidence, and clearly hurt the performance of the Czech economy.

On the research front, a great deal of attention has been given to the economics and politics of large-scale institutional change. One of the most debated questions is the relative merits of ‘shock therapy’—the rapid movement along as many fronts as possible to the desired institutional configuration. Lipton and Sachs (1990) and Sachs (1993) provide early arguments for moving quickly. In the gradualist camp, Roland (2000) outlines models that suggest the merits of a more phased approach, particularly when the outcomes of the reform process are uncertain.

4. The Road Ahead

In highlighting the difficulties of transition, the momentousness of the achievement must not be missed. Political and economic freedoms have been restored; the state has largely withdrawn from the ownership and control of productive resources; and markets have been allowed to exist and to flourish. The capitalist political–economic system, though not flawless, has proven its capacity to generate growth and improvements in living standards (see Maddison 1995). In contrast, the communist system brought repression, and eventually stagnation. The future should be bright for those countries that continue to advance down the road to a free economy (see Kornai 1990).

At the outset of transition, Eastern European politicians said their goal was ‘to return to Europe’ (Sachs 1993). The ultimate expression of such a return would be accession to the European Union (EU). For the more advanced reformers, this goal should be in reach within the first decade of the twenty-first century. The process of accession will be difficult, of course, forcing combinations of further liberalization and the adoption of often-costly EU regulations. Meeting the convergence criteria for joining the Economic Monetary Union (EMU), and thus the right to adopt the euro currency could be especially painful. Moreover, easy immigration to the richer countries to the west could drain the Eastern European of talent needed to rebuild their economies. Nonetheless, accession would be a remarkable achievement, given where these economies started from at the beginning of the 1990s. It would also mark a clear date for the end of transition.

Bibliography:

- Blanchard O 1997 The Economics of Post-Communist Transition. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Blanchard O, Kremer M 1997 Disorganization. Quarterly Journal of Economics, CXII(4)

- Boone P, Horder J 1998 Inflation: Causes, consequences, and cures. In: Boone P, Gomulka S, Layard R (eds.) Emerging from Communism: Lessons from Russia, China, and Eastern Europe. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Boycko M, Shleifer A, Vishny R 1995 Privatizing Russia. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Calvo G, Coricelli F 1992 Stabilizing a previously centrally planned economy: Poland 1990. Economic Policy 14

- Estrin S 1998 Privatization and restructuring in Eastern Europe. In: Boone P, Gomulka S, Layard R (eds.) Emerging from Communism: Lessons from Russia, China, and Eastern Europe. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development 1995 Transition Report: Investment and Enterprise Development. EBRD, London

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development 1999 Transition Report: Ten Years of Transition. EBRD, London

- Frydman R, Gray C, Hessel M, Rapaczynski 1999 When does privitization work? The impact of private ownership on corporate performance in the transition economies. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114(3)

- Gomulka S 1998 Output: Causes of decline and recovery. In: Boone P, Gomulka S, Layard R (eds.) Emerging from Communism: Lessons from Russia, China, and Eastern Europe. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- International Monetary Fund 2000 World Economic Outlook (October). IMF, Washington, DC

- Johnson S, LaPorta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A 2000 Tunneling. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings (May)

- Kornai J 1990 The Road to a Free Economy: Shifting from a Socialist System—The Example of Hungary. W W Norton, New York

- Kornai J 1992 The Socialist System: The Political Economy of Communism. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Kornai J 1995 Highways and Byways: Studies on Reform and Post Communist Transition. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA Layard R 1998 Why so much pain? An overview. In: Boone P,

- Gomulka S, Layard R (eds.) Emerging from Communism: Lessons from Russia, China, and Eastern Europe. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Lipton D, Sachs J 1990 Creating a market economy in Eastern Europe: The case of Poland. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1

- Maddision A 1995 Monitoring the World Economy. OECD, Paris

- Milanovic B 1998 Income, Inequality, and Poverty During the Transition from Planned to Market Economy. World Bank, Washington, DC

- Roland G 2000 Transition and Economics: Politics, Markets, and Firms. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Roland G, Verdier T 1999 Transition and the output fall. Economics of Transition 7(1)

- Sachs J 1993 Poland’s Jump to the Market Economy. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Shleifer A, Vishny R 1994 Politicians and firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, CIX(4)