View sample economics research paper on public finance. Browse economics research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Public finance, commonly referred to as public economics, is the field of economics that examines the role of the government in the economy and the economic consequences of the government’s actions. A notable exception to this definition is the study of the government’s effects on the business cycle, which is usually considered to be a part of macroeconomics rather than public finance. Public finance is concerned with both positive and normative economic issues. Positive economics is the division of economics that examines the consequences of economic actions and thus includes the development of theory, whereas normative economics brings in value judgments about what should be done to analyses and often gives recommendations for public policy. Normative economic issues, in fact, are discussed and debated more often in the public finance literature than in the literatures of most other fields in economics.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Public finance covers a wide range of topics, many of which are central to the economics discipline. The public finance literature examines theoretical as well as empirical topics. Some studies focus on macro-issues, and others examine specific economic issues. Notwithstanding this diversity in coverage, most questions addressed by the public finance literature fall into one or more of the following three categories: (1) Under what scenarios should governments intervene in the economy, (2) what are the economic consequences of government interventions in the economy, and (3) why do governments do what they do?

Our present knowledge of public finance is the result of more than 200 years of scholarly contributions. Although originally published in 1776, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith popularized many notions about the proper role of the government that are still very much relevant to today’s world. Adam Smith discussed the following three duties that the government should perform: (1) protect its citizens from foreign invaders by providing national defense; (2) protect members of society from injustices from each other through the provision of a legal system; and (3) provide certain public works, such as bridges, roads, and institutions, including elementary level education (but not secondary and university education).3 Most people, including economists, would agree with Adam Smith that the government should perform these three tasks. Of course, many people believe the government should do even more. Many readers of this research paper may strongly believe the government should provide for the education of students at universities and colleges.

As the role of the government in the economy has changed over time, the focus of the public finance literature has similarly evolved. In the 1950s and 1960s, the emphasis of public finance was largely on issues of taxation. Now, with the government significantly involved in many aspects of the economy, the public finance literature has expanded its focus to include virtually all facets of government spending, as well as taxation. Many advances have been made within the field of public finance over the past several decades, and public finance economists have made substantial contributions to many other fields in economics. For example, the economics of aging, a relatively new economic subfield, has benefited greatly from public finance economists who have provided analysis and policy recommendations for issues pertaining to government entitlement programs for retirees. Many of these topics are of particular importance to Americans. How will the approaching retirement of the baby boomer generation affect the overall level of economic activity? And how will this growth in retirees strain government entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare, and what should the government do, if anything, to these entitlement programs as a result?

Public Finance Theory

The Theory of the Government

When the proper role of the government is under consideration, it is often useful to think about under what circumstances the government can do a better job than private markets. If reliance on private markets’ carrying of economic activities always results in economically efficient outcomes and people are, for the most part, content with the distribution of income and wealth, then there is little or no need for a government role in the economy. However, there are many circumstances where the private market fails to achieve an efficient outcome or the private market outcome results in a distribution of income or wealth that is considered by most people to be very unjust. Sometimes there are market failures. In these situations, society may be better off when actions are conducted by the government, rather than letting economic activities take place solely in private markets.

One task the government can likely do better than private markets is the provision of so-called public goods. The theory of public goods was to a large extent developed by the economist Paul Samuelson.4 To economists, public goods are not the same things as goods provided by the public sector. Rather, public goods are goods that have the following two qualities: (1) nonrivalry and (2) nonexcludability. In comparison, private goods have both rivalry and excludability. Nonrivalrous goods are goods for which consumption by one consumer does not prevent or diminish simultaneous consumption by other consumers. On the other hand, a good has rivalry if consumption by one consumer prevents or diminishes the ability of other consumers to consume it at the same time. A slice of pizza is clearly a rivalrous good. Nonexcludability means it is not possible to prevent people who have not paid for it from enjoying the benefits of it. Air is an example of a nonexcludable good. National defense is a public good, because it has both nonrivalry and nonexcludability in consumption. Although the government provides many public goods, it also provides many private goods, such as health care, school lunches, and Social Security.

The free-rider problem is a primary cause of private markets’ failure to efficiently provide public goods. Because people benefit from public goods regardless of who in society pays the costs of providing them, people have an incentive to spend too little on public goods themselves and instead take a free ride on the contributions of others. Therefore, when private markets provide public goods, too little is often spent on their provision. The government can correct this market inefficiency by taxing members of society and using this tax revenue to provide an efficient amount of public goods. On the other hand, taxes also cause market inefficiencies, a matter that is discussed later in this research paper.

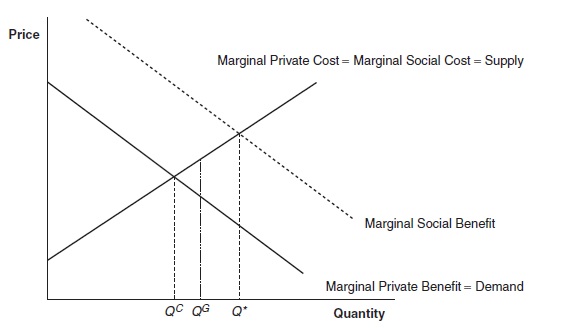

The problems associated with the provision of public goods can alternatively be discussed in the framework of private and social costs and benefits. The marginal private benefit is the incremental benefit of an activity for private individuals or businesses engaged in that activity, whereas the marginal social benefit measures the incremental benefit of an activity for society. Marginal private costs and marginal social costs are similarly defined. Therefore, the demand and supply curves are the same as marginal private benefit and marginal private cost curves, respectively. Public goods create a positive externality, which is to say that public goods provide external benefits. The external benefit or positive externality is measured by the amount to which social benefits exceed private benefits. In other situations, there are negative externalities. A negative externality exists when the social cost exceeds the private cost.

Figure 1 illustrates the case for a positive externality. When the provision of the public good is left to private markets, individuals will purchase units of the public good until their marginal private costs are equal to their marginal private benefits. In other words, marginal private cost is the supply curve, and marginal private benefit is the demand curve. For the overall market, the quantity ofthe public good provided, Qc, at the competitive equilibrium is not economically efficient. More specifically, too little of the public good is provided by the private market. Notice that at the competitive equilibrium (where supply equals demand), the marginal social benefit still exceeds the marginal social cost. The economically efficient outcome, Q*, occurs where the marginal social benefit is equal to the marginal social cost. There are potential social gains to government intervention if the government’s actions result in an increase in the quantity of the public good that is closer to the economically efficient outcome than the competitive equilibrium. For example, QG in Figure 1 is one possible outcome of government intervention that results in a more economically efficient outcome than the competitive equilibrium.

Under certain circumstances, government intervention is not needed to correct the externality problem because the private market will be able to solve the externality problem on its own and provide an economically efficient outcome. The Coase Theorem, attributed to Ronald Coase, provides the conditions where the market may work efficiently even if externalities are present. The Coase Theorem states that when property rights are well defined and the transaction costs involved in the bargaining process between the parties are sufficiently low, the private market may provide an economically efficient outcome even though externalities are present.

How the Coase Theorem works can be illustrated with a simple example. Suppose Jack and Jill live next door to each other and Jack is contemplating planting a flower garden in his front yard. The flower garden will cost Jack $50 to plant (because of seeds, water, fertilizer, and labor) and will provide him a benefit equal to $40 because of its beauty. The flower garden will also provide an external benefit to Jill equal to $20. This positive externality arises because Jill will get to enjoy the beauty of the flower garden even though she does not own it. Clearly, from a social viewpoint, the flower garden should be planted, because it has a total social benefit of $60, which exceeds its total social cost of $40. Nonetheless, Jack will not plant the flower garden if he has to rely solely on his own funding, because his private benefit of $40 is less than his private cost of $50. The first condition of the Coase Theorem—that property rights are well defined—is met, because Jack has the property rights over whether to plant the flower garden. Suppose further that Jack and Jill can bargain over the planting of the flower garden at zero cost. With this assumption, the second condition of the Coase Theorem—that the transaction costs of bargaining are sufficiently low—is also met.

Figure 1. Effects of a Tax

Now, let us see the Coase Theorem in action: Jill would be willing to pay Jack an amount that is sufficiently high to induce him to plant the flower garden. As a result of this side payment, both Jack and Jill would be better off, because the flower garden will be planted and the efficient economic outcome will arise. For example, if Jill pays Jack $15 to plant the flower garden, her total benefit of $20 exceeds her total cost of $15. Similarly, for Jack, his total benefit would be $55 ($40 from getting to enjoy the flower garden and $15 from Jill), which exceeds his total cost of $50.

When only a few parties are involved in situations of externalities, the transaction costs of bargaining may very well be sufficiently low, like in the above example, and private markets may be able to correct the problem of externalities on their own, providing an economically efficient outcome. In fact, judges and legal scholars sometimes use the Coase Theorem as a guide for thinking about proper solutions to tort cases involving public nuisances.

Unfortunately, many serious situations of externalities involve many parties, and the costs of bargaining are prohibitively high. For example, situations where companies are polluting the air or water often involve many victims, and bargaining between all the parties involved would be a very costly and complicated process. It is farfetched to think that private markets can solve problems of externalities and achieve economically efficient outcomes on their own in situations of industrial pollution. In these cases, government intervention in the marketplace could improve on the private market outcome. In fact, government intervention in situations where there is degradation of the environment is common.

So far, the discussion of the government has focused on what the proper role of the government should be and how the government can improve on outcomes left solely to actions of private markets. However, economists are also interested in why governments do what they do. The subdiscipline of public finance called public choice tries to explain how democratic governments actually work, rather than how they should work. The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy, coauthored by James M. Buchanan and Gordon Tullock (1962), is considered by many economists the landmark text that founded public choice as a field in economics. Although public choice shares many similarities with political science, public choice economists assume that voters, politicians, and bureaucrats all act predominately in their own self-interest, rather than in the interests of the public good.

The Theory of Taxation

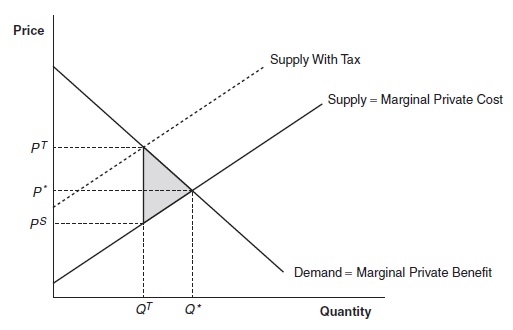

A natural starting point for examining the modern theory of taxation is Richard Musgrave’s 1959 textbook, The Theory of Public Finance. Musgrave’s public finance text was the first to look like a present-day economics textbook, using many algebraic equations and graphs to illustrate the economic effects of government policy. Musgrave’s textbook provides a thorough partial equilibrium analysis of taxation. Partial equilibrium analysis examines the equilibrium in one market without factoring in ripple effects on other markets. In comparison, general equilibrium analysis examines the entire economy, and therefore, it takes into account cross-market effects. Two important economic questions of taxation are (1) what is the incidence of the tax and (2) how large is the loss in economic efficiency from the tax? The deadweight loss of the tax is another term for the economic efficiency loss of the tax. Tax incidence measures how the burden of a tax falls on different members of society. In practically all cases, taxes create economic inefficiencies through the distortion of incentives.

Figure 2 illustrates the concepts of tax incidence and deadweight loss within the partial equilibrium framework. Without a tax, the competitive equilibrium occurs where the demand equals supply at a price of P* and a quantity of Q*. The equilibrium with no tax is economically efficient because the marginal social cost is equal to the marginal social benefit. Now, suppose a tax is imposed. The tax shifts up the supply curve vertically by the amount of the tax per unit.5 The equilibrium quantity with the tax, QT, is below the equilibrium quantity without the tax, Q*. The tax distorts market behavior in an inefficient manner, which is evident because the units between QT and Q* are not being bought and sold when the tax is imposed, even though the marginal social benefits of these units exceed their marginal social costs. The deadweight loss of tax is represented by the triangle shaded in gray. Notice that the tax puts a wedge between the price consumers pay, PC, and the price sellers get to keep net of the tax, P33. The tax revenue per unit that the government receives is measured by the difference between the consumer price and seller price (PC – PS).

The tax incidence is examined by comparing how much of the tax falls on consumers and how much falls on sellers. The dollar amount of the tax per unit falling on consumers is equal to the price consumers pay, with the tax subtracted from the price they pay without the tax (PC- P*). Similarly, the dollar amount of the tax per unit falling on sellers is equal to the price sellers receive, without the tax subtracted from the price sellers receive with the tax (P* – P33). The addition of the dollar amount of the tax per unit falling on consumers to the dollar amount falling on sellers equals the amount of the tax per unit (PC – PS). In the example illustrated in Figure 2, the tax burden falls disproportionately on consumers.

It is important to note that how much of the tax collected from consumers, as opposed to sellers, has absolutely no effect on either the incidence or the deadweight loss of the tax. In Figure 2, the tax is levied entirely on sellers, as is evident by the tax raising the marginal cost exactly by the amount of tax per unit. Alternatively, if the tax were levied entirely on consumers, the demand curve would have shifted vertically downward by the amount of the tax per unit. In both cases, the consumers’ net price, the sellers’ net price, and the size of the deadweight loss are all exactly the same.

The elasticity of demand and the elasticity of supply are the factors that determine the incidence and deadweight loss of a tax. Some generalizations can be made about how the elasticity of demand and supply influence the tax incidence and the size of the deadweight loss of a tax. The more inelastic the demand or the supply, all else equal, the larger the share of the tax burden that falls on consumers and the smaller the share that falls on sellers.

Figure 2. External Private Benefits

Additionally, the more elastic the demand or the supply, the larger the deadweight loss of the tax will be. For example, suppose a tax is imposed on gasoline, a product with a relatively inelastic demand. The burden of this tax will fall primarily on consumers of gasoline, even though governments collect this tax from sellers. Furthermore, because the demand for gasoline is relatively inelastic, the deadweight loss of the tax will be relatively small because there will be a relatively small change in the quantity of gasoline bought and sold.6 Although partial equilibrium analysis is helpful for understanding many issues of taxation, it is inadequate for providing profound insight about some important economic issues surrounding taxation. For instance, partial equilibrium analysis often cannot adequately describe the incidence and deadweight loss of taxes for situations where there are multiple products and multiple sectors of the economy. Additionally, partial equilibrium analysis is not useful, in most cases, for determining the optimal tax structure of the tax system (e.g., how much of the tax rates should be on wages, savings, and different products). To examine these issues of taxation, public finance economists rely on general equilibrium models.7

The scholarly work by Arnold Harberger shows how the techniques used to measure the incidence and deadweight loss of taxes in the partial equilibrium framework can be extended to situations with multiple products and sectors, including the case of the corporate income tax. The deadweight loss resulting from a tax or some other type of distortion, such as a price floor or a price ceiling, is often referred to as Harberger’s Triangle. In Figure 2, Harberger’s Triangle is the triangle shaded in gray.

The incidence of a tax may differ widely depending on whether the economy is opened or closed (i.e., whether the economy, for the most part, freely trades with other economies).8 Harberger (1962) examines the corporate tax incidence with a general equilibrium model of a closed economy that has two sectors (corporate and noncorporate) and two factors (labor and capital). Harberger (2008) has recently revisited his work on the incidence of the corporate tax. For the interesting case where product demands and the production functions in both sectors conform to the commonly used Cobb-Douglas functional form, the entire burden of the corporate income tax falls on capital. In comparison, models that assume the economy is opened often find that much of the burden of the corporate income tax is shifted to labor.

Economic theories have addressed the design of an optimal system of taxation, a topic related to the measurement of the deadweight loss of taxes. Although taxes create losses in economic efficiency by distorting people’s behavior, they are needed to generate revenues for a society to pursue its social objectives. Theories of optimal taxation look for the system of taxes that minimizes the economic efficiency costs of taxes, subject to constraints, such as the types of taxes and information that are available to the government. Theoretical inquiries into optimal taxation fall into one of the following three categories: (1) the design of the optimal system of commodity taxes; (2) the design of a general system of taxation, including nonlinear taxes on income, with a focus on the role of taxes for addressing concerns about inequality; and (3) the role of taxes to address market failures. The first strand began with the work by Ramsey (1927) and has been added to, most notably, by Peter Diamond and James Mirrlees (1971a, 1971b). The Ramsey tax rule says that under a tax system composed only of commodity taxes, the optimal tax rates are higher for commodities with more inelastic demands. Thus, the optimal tax rate is higher for gasoline than for pretzels, assuming that gasoline is more inelastically demanded than pretzels. The work by Mirrlees (1971) was the first in the second strand of theory. Finally, the seminal work by Arthur Pigou (1947) provides the foundation for work in the third strand of theory. A Pigouvian tax is levied to correct a negative externality. For example, suppose that the production of widgets has a constant $1 external cost. The government can fully correct this negative externality by imposing a constant $1 tax per widget. When this tax is imposed, widget producers will act as if their private costs are equal to the social costs, and the economically efficient outcome will prevail.

The extent to which economic inputs into production, such as labor and capital, are mobile has significant implications for taxation as well as for many other aspects of public finance. Economists have developed theoretical models to examine the effects of tax competition—a situation where governments lower taxes or provide other benefits in an effort to encourage productive resources to relocate within their borders—on tax rates, tax incidence, and on the distribution of resources across regions. Tax competition can occur between countries, states, or smaller units of government.

Also related to factor mobility is the Tiebout model, developed by Charles Tiebout (1956). Tiebout’s insight is that the free-rider problem pertaining to public goods is different in the context of local governments because they offer bundles of goods and services and taxes to potential residents because people are able to take into account, when deciding where they want to live, the governmental amenities and disamenities offered by the various localities. In the Tiebout model, competition among local governments and people’s ability to vote with their feet effectively solves the free-rider problem and results in an economically efficient provision of public goods by local governments. When people have different tastes for amenities, the Tiebout model predicts that there will be locational sorting based on individuals’ preferences. For example, people with children will choose to live in locations with high tax rates for schools and well-funded public schools, whereas people without children, such as retirees, will choose to live in locations with low school tax rates and poorly funded public schools.

Applications and Empirical Research

The empirical public finance literature has made significant strides over the past several decades. Several factors, including advances in computer technology, econometric techniques, and software, have contributed to improvements in both the quality of research and to the exploration of new avenues of research in public finance. Additionally, new data sets containing valuable information at the individual and household levels have been created, and this has allowed researchers to better examine empirical phenomenon. Some of the significant findings in the empirical public finance literature are discussed below, although because of the great breadth of the empirical literature, it is not possible to highlight every important area of empirical research.

Public finance economists have exploited changes in tax policy and individual and household-level data, such as the public use tax model files generated by the Internal Revenue Service’s Statistics of Income Division, to measure how work incentives are distorted by tax policies. Empirical studies typically have found that the overall number of hours worked by men is not very responsive to changes in income tax rates. The high degree of inelasticity of the male labor supply implies that the burden of the income tax falls squarely on male workers, rather than employers, and that small increases in income tax rates are unlikely to create large deadweight losses from distortion of the incentives to work.

Even though, overall, the policy of income taxation may have a negligible effect on the aggregate supply of labor, income tax policy may significantly influence the labor supplies of specific groups of individuals and in specific markets. The labor supply of women, particularly married women, has been found to be much more elastic than the labor supply of men. Therefore, increases in income tax rates may cause significant numbers of married women to focus on household production instead of working in the workplace. Some studies have found that high marginal tax rates may induce some workers to leave legitimate occupations for work in the underground economy to avoid paying taxes. Also, the income tax policy pursued by a particular state may affect the labor supply of that state via migration. Some evidence suggests that workers tend to migrate from states with high income tax rates to states with low income tax rates.

Besides influencing labor supply, tax policy affects many other types of economic activity. Of particular interest is the effect of tax policy on savings decisions. Some economists have argued that lowering the tax rate on capital income increases savings because it increases the after-tax rate of return on investing. However, the theoretical and empirical evidence of the effect of tax rates on capital income and savings has been ambiguous. For example, if someone is saving with the explicit goal of accumulating $50,000 in 3 years for a down payment on a house, a reduction in capital income taxes will lower the amount this person needs to save now, because he or she can achieve the savings goal by saving less. Along these lines, more specific literature has examined how changes in tax policy that have given preferential treatment to retirement savings through contributions to IRA, 401(k), and other retirement plans have influenced aggregate retirement savings. Although some empirical evidence has indicated that this preferential tax treatment has had a positive influence on retirement savings, additional empirical analyses are still needed to develop a clearer understanding of this relationship.

Over the past 50 years, the role of the government in the economy has greatly expanded in terms of scope and magnitude, particularly regarding government spending on nondefense items. Nondefense spending by the federal and state governments in real 2007 dollars has increased almost fivefold between 1960 and 2007, from $686 billion in 1960 to $3,256 billion in 2007.9 Spending by local governments has similarly swelled over this time period. This large expansion of the government has motivated public finance economists to examine the empirical effects of spending on a wide range of government programs.

Social insurance programs have been the recipients of much of the growth in government spending. A vast number of empirical studies have examined the economic issues for a host of social insurance programs, including Social Security; government health care programs for the elderly and poor, such as Medicare and Medicaid; unemployment insurance; worker’s compensation; programs that provide subsidies to the poor, such as Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC); and many other programs. Empirical research has found that social security programs in the United States and in other countries have reduced aggregate savings and produced early retirements. Studies have also examined the general equilibrium effects of Social Security reform, which would switch the current pay-as-you-go system to a system at least in part based on investment accounts similar to private retirement savings accounts. Many empirical studies on Medicaid and Medicare have focused on issues of adverse selection and moral hazard. Other studies have examined the potential fiscal impacts of continued growth in spending on Medicaid and Medicare.

The economic effects of government antipoverty programs have been the focus of many empirical studies. TANF is the primary welfare program in America today. In 1997, it replaced its predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). In contrast to AFDC, TANF has strict time limits for assistance and places a strong emphasis on vocational training, community service, and the provision of childcare. Although more empirical work is still needed to sort out all of the economic impacts of TANF, one finding without controversy is that the switch to TANF has undoubtedly caused a large reduction in welfare caseloads. In terms of enrollment, EITC is the largest government antipoverty program. EITC supplements the earnings of low-wage workers with a tax credit. This program may reduce the total hours worked of some workers and cause others to switch to lower-paying but more enjoyable occupations so that they can qualify for the tax credits. Notwithstanding these negative effects on labor supply, many empirical studies have found that EITC has increased the overall rate of labor force participation, particularly among single parents, by increasing the marginal benefit of working.

The structure of many government programs, such as public education, involves a complex interrelationship among the several tiers of government: federal, state, and local. Fiscal federalism is the subfield of public finance that examines the economic effects of having public sector activities and finances divided among the different tiers of government. A central question addressed by fiscal federalism is what aspects of the public sector are best centralized and what functions are best delegated to lower tiers of government.

Many empirical studies related to fiscal federalism have examined the economic effects of intergovernmental grants. The federal government gives grants to state and local governments for a variety of governmental programs, including those for public education, welfare, and public roads and highways. Many types of earmarks, such as the earmarking of state lottery revenues for educational funding, conceptually have the same economic effects as grants. According to standard economic theory, a lump-sum amount of intergovernmental aid given to a lower tier of government for an activity should have the same effect on spending for this activity as an increase in private incomes (Bradford & Oates, 1971). For example, a federal grant increase of $50 per taxpayer given to states for education should, theoretically, increase educational spending in the same manner as an earnings increase of $50 per taxpayer per year.10 Therefore, grants and earmarks should have a minimal impact on total spending. Many empirical studies, however, have rejected the fungibility of intergovernmental aid, finding instead that the money given to lower tiers of government “sticks where it hits.” As a result, this phenomenon is referred to as the flypaper effect, a term attributed to Arthur Okun. The findings in the empirical literature, however, are mixed. Some recent studies have found that local and state funding is substantially cut in response to funding from federal grants, particularly after time has elapsed since the federal aid was first received.

The Tiebout model outlined previously has spawned a rich empirical literature. Many empirical studies have built on Tiebout’s work, using people’s processes in choosing where to live to estimate the demands for local public goods, such as public education, and to measure how property values reflect local amenities and taxes. Empirical research has also used the Tiebout model as a foundation for explaining that the prevalence of restrictive zoning laws in many urban communities is a device to prevent free riding: buying inexpensive homes with low property tax assessments in areas where most residents own expensive homes with high property tax assessments. Additionally, the Tiebout model has influenced the fiscal federalism literature; many empirical studies have examined the proper roles of the different tiers of government.

Public Policy Implications

It is not surprising that public finance has a wide array of implications for public policy, given that the focus of public finance is on the government’s role in the economy and the economic effects of its actions. Much of the theoretical and empirical public finance literature has direct relevance for issues of public policy. Public finance economists work in all levels of government. They carry out a variety of important administrative functions and provide crucial advice and analyses to government decision makers. Public finance economists perform important public policy roles at all federal government agencies, including the Joint Committee of Taxation, the Congressional Budget Office, the United States Department of Agriculture, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Homeland Security. All state governments, and many county and city governments, also employ public finance economists, largely for their advice and analyses on issues of public policy. Even the public finance economists that are not directly employed by the government, working instead at universities and public policy institutions, directly influence debates of public policy through their research, writings, and consulting activities.

In their endeavors, public finance economists are influencing how to best address the key public policy issues of today. Here are just a few of the questions in the current debates over public policy that public finance economists are now trying to answer: What is the best way to keep Social Security sustainable without inducing severe distortions on work incentives? How should the federal government expand the coverage of heath care? How can federal and state governments best support local governments in their efforts to improve underperforming public schools? Should a state government lower corporate taxes to induce new businesses to relocate to their state?

Of course, public policy makers do not always heed the advice of public finance economists, nor do they always properly take into account the findings of economists when deciding on a course of action. In other situations, public policy makers receive conflicting advice from public finance economists, a result of vehement disagreement among economists over the proper course of action for issues of public policy. Nonetheless, the large number of public finance economists actively working with elected officials and other policy makers indicates that the field of public finance often does effectively influence public policy.

Future Directions

In recent years, empirical research has flourished in the field of public finance. Every indication suggests that empirical research in public finance will continue to thrive in the near future. Advances in computer technology and econometric software will likely continue. New rich data sets will be created. Additionally, many new topics ripe for empirical analysis will surely arise. Governments will continue to tinker with tax policy. Reform and expansion of government social security programs will remain hotly debated topics. And the multiple tiers of government will continue to work together for providing many government programs, such as public education.

Many issues related to globalization will likely receive a lot of attention from public finance economists in the near future. By lowering the costs of capital and labor mobility across international borders, globalization has significant implications for many aspects of public finance, particularly for tax policy. Historically, some actors and rock stars have moved from one country to another, seeking lower taxes. Globalization has made this a viable option for a much larger segment of the world population. Internationally, capital is even more mobile than labor. Tax competition to induce businesses and residents to locate somewhere is no longer merely a local issue but an international one. Future research topics involving globalization will likely include how changes in tax policy induce international movements of labor and capital and how countries coordinate tax policy with each other.

The international financial crisis and federal financial bailout approved in the fall of 2008 will surely provide fruitful opportunities for future research in public finance. Many public finance issues are directly related to the federal bailouts. The federal financial bailout has important ramifications for issues related to tax burden and tax incidence, particularly if taxpayers are not fully reimbursed by the bailed-out industries. The federal bailout also involves many short- and long-run budgetary concerns. Another implication of the federal bailout is further expansion of the role of the government. Bailouts are already under way for the automobile industry. Will bailouts for other industries follow? Public finance economists will certainly examine the effectiveness of cooperation between the private sector and public sector officials.

Conclusion

Public finance is the field of economics concerned with the role of the government in the economy and the economic consequences of the government’s actions. Both positive and normative economic issues are discussed and debated in the public finance literature. Normative issues receive more attention in the public finance literature than in many other economic fields. Public finance theories examine taxation and government spending. Many theoretical advances have been made in public finance over the past 50 years. Theories of taxation examine tax incidence, economic efficiency costs of taxes, and the optimal design of systems of taxation. Issues of income inequality are sometimes taken into account by theoretical studies of the optimal design of taxation. The development of general equilibrium models has made important contributions to our theoretical understanding of taxation. Theories of government spending fall under two broad categories. First, some theories of government spending focus on the proper role of the government, examining the circumstances in which society is made better by government intervention in the economy. Second, some theories of government spending are more interested in why the government does what it does. In particular, the subfield of public choice is interested in why governments behave as they do. More recently, the empirical public finance literature has made great strides that have significantly added to our understanding of public finance. The empirical public finance literature has flourished, largely because of advances in computer technology, econometrics, and the creation of data sets with information at the household or individual level. A vast empirical literature now covers virtually every facet of taxation and government spending.

In the coming years, public finance economists will likely continue to advance our knowledge of the field and play an important role in influencing key debates over public policy issues. Globalization and the federal financial bailout that began in the fall of 2008 are two topics that surely will receive a lot of attention from public finance economists in the near future. It is to be hoped that public policy makers will rely on the advice and analyses offered by economists, many of whom specialize in public finance, to make wise decisions about the role of the government in the economy and to get us through the difficult economic times we now are experiencing.

Bibliography:

- Auerbach, A. J., & Hines, J. R. (2002). Taxation and economic efficiency. In A. J. Auerbach & M. Feldstein (Eds.), Handbook of public economics (pp. 1347-1421). New York: Elsevier.

- Bradford, D. F., & Oates, W. E. (1971). The analysis of revenue sharing in a new approach to collective fiscal decisions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 85, 416-439.

- Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1-44.

- Diamond, P. A., & Mirrlees, J. A. (1971a). Optimal taxation and public production 1: Production efficiency. American Economic Review, 61, 8-27.

- Diamond, P. A., & Mirrlees, J. A. (1971b). Optimal taxation and public production 2: Tax rules. American Economic Review, 61, 261-278.

- Feldstein, M. (2000). The transformation of public economics research: 1970-2000. In A. J. Auerbach & M. Feldstein (Eds.), Handbook of public economics (pp. xxvii-xxxiii). New York: Elsevier.

- Gruber, J. (2007). Public finance and public policy. New York: Worth.

- Harberger, A. C. (1962). The incidence of the corporation income tax. Journal of Political Economy, 70, 215-250.

- Harberger, A. C. (2008). The incidence of the corporation income tax revisited. National Tax Journal, 61, 303-312.

- Johnson, H. G. (1974). Two-sector model of general equilibrium. Portland, OR: Book News, Inc.

- Mirrlees, J. A. (1971). An exploration in the theory of optimum income taxation. Review of Economic Studies, 38, 175-208.

- Musgrave, R. A. (1959). The theory of public finance. NewYork:McGraw-Hill.

- Musgrave, R. A. (1985). A brief history of fiscal doctrine. In A. J. Auerbach & M. Feldstein (Eds.), Handbook of public economics (pp. 1-54). New York: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Office of Management and Budget. (1960). Budget of the United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Office of Management and Budget. (2007). Budget of the United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Pigou, A. C. (1947). A study in public finance. London: Macmillan.

- Ramsey, F. P. (1927). A contribution to the theory of taxation. Economic Journal, 37, 47-61.

- Rosen, H., & Gayer, T. (2007). Public finance. New York:McGraw-Hill.

- Samuelson, P. A. (1954). The pure theory of public expenditure. Review of Economics and Statistics, 36, 387-389.

- Smith, A. (1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. London: Methuen & Sons.

- Tiebout, C. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64, 4 1 6-424.

- Tresch, R. W. (2002). Public finance: A normative theory. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Wise, D. A. (Ed.). (1998). Inquires in the economics of aging (National Bureau of Economic Research Project Hardcover). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.