Sample International Marketing Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

International marketing has grown out of the weaknesses of international trade theory which considered no differences in local consumer tastes and preferences and did not take into account the possibility for firms to launch marketing operations directly on foreign markets through sales subsidiaries. Definitions of international marketing are first examined, followed by a review of the central debate in this field, that is, whether products and marketing strategies should be standardized for increasingly globalized world markets or whether they should be tailored to local consumer needs and marketing environments. With the emergence of global markets, culture now appears as a prominent variable for international marketing decisions. The third section explains how cross-cultural differences must be taken into account to highlight significant differences in areas such as consumer behavior, market research, and advertizing practices. An in-depth understanding of what is global and what remains local is a key input for designing successful international marketing strategies.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Definitions Of International Marketing

1.1 Traditional Definitions Of International Marketing

The early definitions of international marketing in the 1950s emphasized foreign market operations, that is, the distribution of products abroad and the development of marketing channels and consumer franchise in foreign countries as ways and means to reach larger customer bases. As a consequence, emphasis was put on developing stable relationships with agents and dealers in foreign countries. This view of international marketing was linked largely to international business concerns such as the choice of the right mode of entry, the assessment of political risk in target countries, and the logistics of international marketing.

In the 1970s, with growing foreign direct investment of multinational companies, international marketing more and more has focused on the design of marketing strategies for local markets and their co-ordination within world markets (Wind et al. 1973). The understanding of local peculiarities in consumer behavior and marketing environments increasingly was considered as a required step in the definition of marketing strategies in an international context. The 4Ps paradigm of marketing (product, price, place, promotion) has been applied extensively to foreign markets, considering how to adapt products to local tastes and requirements, to adjust price policies internationally, and manage local distribution channels and advertizing campaigns in diverse areas of the world. International marketing has, therefore, been a replication and extension of marketing knowledge ‘made in the USA.’ Up to the 1980s this process has been implemented pragmatically with much respect for local contexts through customized marketing strategies. However, the issue of coordination of marketing strategies across national markets, either at the regional or global level, has emerged as a key organizational issue in the 1980s and 1990s for multinational companies. More centralized control of exceedingly independent subsidiaries has been required because the increasing globalization of the world economy imposes large-scale operations.

1.2 International Marketing As The Diffusion Process Of Marketing Knowledge

Marketing concepts and practices were developed initially and for the most part in the United States and have been popularized by Kotler’s Marketing Management in its numerous translations and editions (Kotler 1994). Most of the books on marketing management were borrowed from the United States and then translated directly without much adaptation. As Van Raaij (1978) stated concerning consumer research: ‘Consumer research is largely ‘‘made in the USA’’ with all the risks that Western American or middle-class biases pervade this type of research in the research questions we address, the concepts and theories we use, and the interpretations we give.’

However, the success of the word ‘marketing’ gave a new image to trade and sales activities in countries where previously it had been socially and intellectually devalued. Despite the success and the seemingly general acceptance of the term ‘marketing’ at the international level, there have been some basic misconceptions of it in many countries, marketing often being reduced to one of its dimensions such as market research, sales promotion, or advertizing. Marketing knowledge has been imported progressively, first plainly, as universal and explicit knowledge, then merged with local tacit knowledge and ways of doing. In many countries, marketing superimposed itself on local selling practices and merged with them rather than replaced long-established commercial practices. As Lazer et al. (1985) point out in the case of Japan: ‘what has occurred (in Japan) is the modification and adaptation of selected American constructs, ideas, and practices to adjust them to the Japanese culture, that remains intact.’

2. The Adaptation Standardization Debate In International Marketing

2.1 The Trend Towards The Globalization Of Markets

As advocated by Levitt (1983), we see the emergence of global markets for standardized consumer products on a previously unimagined scale of magnitude. Ancient differences in national tastes would tend to disappear, while local consumer preferences and national product standards would be ‘vestiges of the past.’ Consumers world-wide would look for good quality low-cost products and global competitors would seek to standardize their offer everywhere. In Levitt’s words it would ‘not (be) a matter of opinion but of necessity’ (1983).

However, globalization is a process that occurs mostly at the competition level. The GATT treaty (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) and the WTO (World Trade Organization) progressively have replaced tariff and nontariff barriers by entry barriers related to scale of operations, marketing knowledge, and corporate experience. As far as consumer behavior and marketing environments are concerned, natural entry barriers related to culture and language diminish progressively and only in the long term. There are still many different marketing ‘villages’ rather than a ‘global village.’

The globalization of consumption displays a complex pattern of mixed global and local behavior. On the one hand, here is striking convergence as concerns basic demographics, for instance, the population, comprises more and more older persons, the size of households is constantly decreasing, and the proportion of immigrants is increasing in most countries, with higher concentration in large cities. The same convergence phenomenon is to be observed for the sociocultural environments in the form of growing equality between men and women and increasing percentages of working women, while health and environment concerns are on the rise. Convergence in consumer behavior can be observed at a broad level: services tend to replace durables in household budgets and demand is growing for healthcare, environmentally friendly, fun, and convenience products (Leeflang and Van Raaij 1995)

2.2 How To Design ‘Globalized’ International Marketing Strategies

The real issue is not a dichotomous choice between total adaptation or full standardization since international marketing performance has been shown to be a combination of both adaptation and standardization strategies (Shoham 1996) and to depend on a large number of factors related to the four components of the marketing mix (Baalbaki and Malhotra 1995). Around a core product offering that is standard worldwide, most global companies such as Coca Cola or McDonald’s customize when needed. Product customization may also result in market differentiation thus creating a competitive advantage vis-a-vis actual competitors and raising entry barriers against potential competitors. Excellent global companies standardize as much as feasible and customize as much as needed.

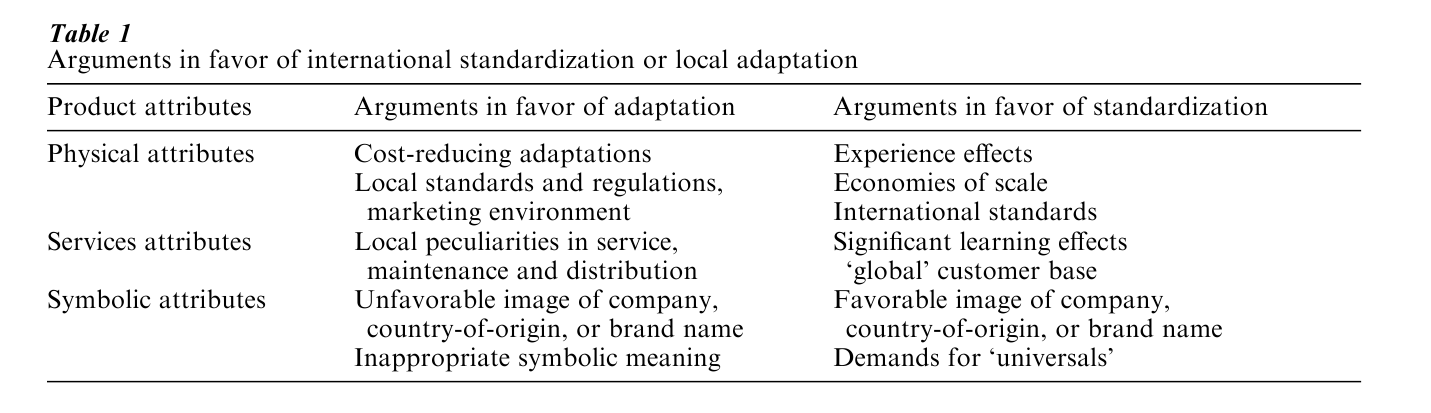

Table 1 proposes a systematic description of arguments in favor of adaptation or standardization, according to the different levels of product attributes: physical, service, and symbolic attributes. Some arguments in favor of either adapting or standardizing originate from within the company which can benefit from changing its way of operating. Other arguments are related to external constraints imposed by the environment, consumer behavior, and regulations: they imply company adaptation to market demand, either by adapting or standardizing its offer.

As concerns the physical attributes, consumer behavior matters a lot, especially the frequency of consumption, the amount consumed per helping, etc. For instance, the required size of a cereal packaging will not be the same in a country where an average consumer eats 50 grams of cereal daily for breakfast and in another country where servings are larger but it is consumed less frequently. Even pizza, a product supposed to be the epitome of international standardization, largely is customized to local tastes. Brand names, although in some rare cases global, need some attention when transferred to foreign markets to avoid unintended meaning.

3. The Emergence Of Culture In The Field Of International Marketing

Traditional international trade doctrine has laid the foundations for a denial of culture in international marketing. Ricardo’s law of comparative or relative advantage is based on the assumption that products and consumers’ tastes, habits, and preferences are perfectly identical across countries. However, quantity and price do not matter solely: local consumers invest meaning beyond the utilitarian aspect of the product. Rather than being merely commoditized, generic, and indefinitely marketable, goods and services increasingly are viewed in international marketing as being singularized and invested with cultural meaning by local consumers who display both utilitarian and nonutilitarian consumption motives.

3.1 Unique Consumption Experiences

Consumption is still largely a local reality. Far from being uniquely related to culture, local consumption reflects also climate, customs, and the mere fact that much of our lives is still experienced, shared, perceived, and interpreted with near people who share the same kind of ‘local knowledge’ in the Geertzian sense (Geertz 1983). Consumption experiences remain local while integrating much global influence because part of the cultural meaning vested in goods and services is now shared world-wide. As noted by Applbaum and Jordt (1996): ‘Globalizing influences have bored intercultural tunnels around the world, but core meaning systems such as those wrapped up in the idea of the family, continue to differ significantly.’ Consumers attribute meaning to products and services in context, especially what it means to desire, to search, to evaluate, to purchase, to consume, to share, to give, to spend money, and to dispose. Consumption experiences are full social facts based on the interaction with other participants in the marketplace such as manufacturers, distributors, salespeople, and other consumers.

For instance, consumption as disposal involves views of what is the appropriate relation to the environment, of what is clean vs. dirty, and of how cleaning efforts should be allocated. Consumption generally leads to the final destruction of goods, this being true also for consumer durables when they are obsolete or out of order. Paper-based products are a good case in point: filters for drip-coffee machines are white in France and yellow-brown in Germany (naturbraun), paper handkerchiefs are generally white in France and yellow-brown in Germany, and toilet paper is generally rosy or white in France and greyish in Germany. The Germans express their willingness to be environmentally friendly (umweltfreundlich) by purchasing paper-based products whose color exhibits their genuinely ‘recycled’ nature, that is, not bleached with chlorine-based chemicals used to whiten recycled paper. The same holds true for the German writing and copy paper whose greyish and irregular aspect would be considered by most of the French as ‘dirty’ and poor quality. The difference in consumer experience lies in the difference of continuity in the ecological concern. Germans are deeply committed to protect their natural environment because they live on a territory about three times more densely populated than France and they insist on strong coherence between pro-environment discourse and actual consumption behavior. The two peoples seem in any case to have different ways of combining and reconciling nature and culture. Understanding local consumer behavior in a cross-cultural perspective (Howes 1996; Sherry 1995) is seen more and more as a prerequisite for the design of sound international marketing policies.

3.2 International Market Research And The Issue Of Cross-Cultural Equivalence

A basic issue in cross-cultural marketing research is to assess whether the concepts used in questionnaires and interviews have similar meaning for respondents in different cultural contexts. For instance the issue of conceptual equivalence has to be addressed before testing the influence of certain constructs on consumer behavior. Such basic concepts as beauty, youth, friendliness, wealth, well-being, sex appeal, and so on often are used in market research questionnaires where motivation for buying many products is related to self-image, interaction with other people in a particular society, and social values. They seem universal. However, it is necessary to question the conceptual equivalence of these words when designing a cross-cultural questionnaire survey. Even the very concept of ‘household’ (widely used in market research) is subject to possible inequivalence: Mytton (1996) cites the case of Northern Nigeria where people often live in large extended family compounds or gida which are difficult to compare with the prevalent Western concept of household which reflects the living unit of a nuclear family. In general, market research measurement instruments adapted to each national culture (the Emic approach) offer more reliability and provide data with greater internal validity than tests applicable to several cultures (the Etic approach, or ‘culture-free tests’). But it is at the expense of cross-national comparability and external validity: results may not be easily transposable to other cultural contexts.

3.3 Understanding How Culture Influences International Marketing Strategies

While being globalized as much as possible, international marketing strategies must be tailored to local consumer behavior, taking into account cultural influences in the design of the 4Ps. For instance, European cars overwhelmingly have manual gearboxes. Europeans do not consider an automatic gearbox as a standard feature for a car, as in the United States, for a number of reasons, certain being related to regulation (driving licenses have to be obtained on a car with a manual gear box, except for handicapped persons), others to deep-seated prejudices (automatic cars consume more petrol) or to social beliefs such as that automatic gear-boxes are only for luxury cars or for handicapped persons (Usunier 1999).

Price is a central element of relational exchange, that is, as a signal conveying meaning between buyer and seller, marketers and consumers, and between companies and their middlemen. In the area of international price policy, it is important to assess which is the dominant price-related behavior: do local consumers tend to use price as a proxy of quality? Do they tend to be price minded? Is bargaining prices a behavior that is considered socially acceptable? Answers to these questions will be key inputs in defining adequate local pricing.

The case of Japanese distribution Keiretsus exemplifies the cultural embedding of distribution channels and the difficulty to enter foreign channels when being a ‘cultural outsider.’ Relationships be- tween channel members are rooted deeply in local patterns of human and economic relationships; distribution appears a ‘cultural filter,’ which must be considered carefully along with other criteria before choosing a foreign distribution channel.

Cross-national variations in sales promotion methods have to be considered when transferring promotional techniques across borders. One must check that the very purpose of the promotional technique is understood locally, a problem in conceptual equivalence. For instance, in many societies being given a free sample is difficult to interpret. Gratuity is understood either as a sign of poor quality (‘they give it because they cannot sell it’) or as a sign of naivety of the manufacturer (‘let’s take as much as possible’). In recent years, Procter and Gamble experienced major problems with free samples in Poland where some people disregarded free samples while others broke mailboxes to steal product samples.

For reasons of image consistency, many companies now try to promote their products globally through standardized advertizing campaigns which use the same advertizing strategy, themes, and execution world-wide. However, marketing communications are based on language, both verbal and nonverbal. Language shapes our world-views in as much as the words we use and the way we assemble them in speech correspond to particular experiences and assumptions about the world in which we live. Advertizing, as the main tool for communicating marketing messages to customer audiences is sensitive to local cultures and languages. Thus, before transferring campaigns cross-nationally, international companies have to decide which elements should be localized and which ones can be similar world-wide in two main areas, advertizing strategy (information content, advertizing appeals, etc.) and advertizing execution (characters and roles represented, visual and textual elements, etc.).

Bibliography:

- Applbaum K, Jordt I 1996 Notes toward an application of McCracken’s ‘cultural categories’ for cross-cultural consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research 23: 204–18

- Baalbaki I B, Malhotra N K 1995 Standardization versus customization in international marketing: An investigation using bridging conjoint analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23: 182–94

- Geertz C 1983 Local Knowledge. Basic Books, New York

- Howes D 1996 Cross-cultural Consumption. Routledge, London

- Kotler P 1994 Marketing Management, 8th edn.. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

- Lazer W, Murata S, Kosaka H 1985 Japanese marketing: Towards a better understanding. Journal of Marketing 49: 69–81

- Leeflang P S H, Van Raaij W F 1995 The changing consumer in the European Union: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing 12: 373–87

- Levitt T 1983 The globalization of markets. Harvard Business Review 61: 92–102

- Mytton G 1996 Research in new fields. Journal of the Market Research Society 38: 19–33

- Sherry J F 1995 Contemporary Marketing and Consumer Behavior. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Shoham A 1996 Marketing-mix standardization: Determinants of export performance. Journal of Global Marketing 10: 53–73

- Usunier J C 1999 Marketing Across Cultures, 3rd edn. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

- Van Raaij W F 1978 Cross-cultural methodology as a case of construct validity. Advances in Consumer Research 5: 693–701

- Wind Y, Douglas S P, Perlmutt H V 1973 Guidelines for developing international marketing strategies. Journal of Marketing 37: 14–23