Sample Household Production Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Household production is the production of goods and services by the members of a household for their own consumption, using their own capital and their own unpaid labor. Goods and services produced by households for their own use include accommodation, meals, clean clothes, and childcare.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The process of household production involves the transformation of purchased intermediate commodities (e.g., supermarket groceries and power-utility electricity) into final consumption commodities (meals and clean clothes). Households use their own capital (kitchen equipment, tables and chairs, kitchen and dining room space) and their own labor (hours spent in shopping, cooking, laundry, and ironing). The total economic value added by households in household production has been aptly named Gross Household Product (GHP) (Eisner 1989, Ironmonger 1996).

1. The Use Of Labor And Capital In Household Production

In the language of economics, labor and capital are the two factors of production. However, labor, the time and effort provided by household members, is really the use of human capital; the second factor of production, capital, is the use of physical or tangible nonhuman capital (the services provided by land, dwellings, vehicles, and equipment). Economics conceptualises the production process as the use of capital (human and other) together with energy, to transform raw materials and ‘unfinished’ commodities (intermediate inputs) into finished goods and services ready for use by people (final consumption).

As countries industrialize, a large part of household production of food, clothing, furniture, and housing is transferred to business organizations and then purchased by households. Nevertheless, even in a world apparently dominated by the market, a large amount of household production is necessary. Households need to add further value to put purchased commodities in the possession of ultimate consumers in the right place and at the right time.

2. Household Production In Contrast To Market And Subsistence Production

2.1 Market Production

While the market economy produces goods and services not produced by households (television sets and battleships), in many cases the market and the household are in direct competition, (restaurant meals vs. home prepared meals, and taxis vs. self-driven owned cars). Restaurants and taxis usually require immediate payment, if not by cash, then by credit card. In households, users do not pay each other by cash or credit card for meals served or transport provided.

Four separate modes of production are possible depending whether the household or the market provides the capital or the labor. Household production occurs when the household provides both its own capital and its own labor. However, the market can provide either one or both of these two factors of production. For example, a housekeeper could be employed to prepare meals, clean the house, and do the laundry. This paid housekeeper’s time would be the use of ‘market labor’ in conjunction with ‘household capital’—the kitchen, dwelling, and household equipment. Again, a household could rent a dwelling and a vehicle (market capital) but do its own cleaning, cooking, laundry, and driving (household labor).

In many countries, the use of paid domestic servants has almost disappeared; servants have been replaced by the household’s own labor combined with more and better household capital and equipment. Many recent developments, such as supermarkets and automatic banking machines, involve a mode of production with households providing the required unpaid labor in lieu of the paid labor of shop assistants or bank tellers.

2.2 Subsistence Production

In developing countries many millions of households use their own capital and unpaid labor by way of fishing, collecting wood and water, growing vegetables and other food, building shelter, and making clothing. Thus, subsistence production fits the definition of household production when the goods produced are used within the household that produced them.

However, the wood, water, food, fiber, and clothing outputs from subsistence production could be sold on the market to other households or to business enterprises. When such commodities are in fact sold, the value added in their production conceptually becomes part of market production.

3. Household Production And The Household Economy

The household economy describes the collective economic activities of households. Often the household economy is called the household sector as distinct from the business, government, and foreign sectors. However, the household sector is large enough to deserve the term household economy. The rest of the economy can then be called the market economy. Thus, the transactions between the household and the market are perhaps more akin to international trade between two economies than transactions between different industrial sectors of a single economy. The two major types of inter-economy trade are the sale of labor time by the household and the sale of household goods and services by the market.

3.1 Households As Producers

With few exceptions, economic textbooks focus on households as consumers and fail to discuss households as producers using their own labor and capital.

One of the earliest writers about the process of household production was Charlotte Perkins Gilman (Women and Economics, 1898) who questioned the traditional gender division of labor. She proposed moving even more household production to the market. This would yield gains from greater specialization and economies of scale and enable women to choose their work on the basis of inclination and talent.

Margaret Reid (Economics of Household Production, 1934) played a significant role in the development of household economics as a discipline, particularly for curricula in some North American universities. She held that, although the household is our most important economic institution, the interest of economists was concentrated on ‘that part of the economic system which is organized on a price basis.’ Reid is regarded as the first writer to specify the often-used third person criterion to distinguish between productive and nonproductive (consumption) activities. Her test was: ‘If an activity is of such character that it might be delegated to a paid worker, then that activity shall be deemed productive’ (Reid 1934). Thus, preparing a meal is productive work but eating it is nonproductive consumption or leisure. Of course eating and other consumption activities are productive in the sense that they are necessary for the continuation and re-invigoration of life. Another problem with this criterion is that student educational activities are classed as unproductive since you would not learn to play the piano by paying someone to take the lessons for you.

A further problem is that production almost always requires a contribution from capital as well as from labor. The criterion needs to be extended to include services that might be obtained from rented capital as well as from a paid worker. Thus, accommodation services provided by a household’s own dwelling are production; so are the transport services provided by a household’s own vehicles and the entertainment services provided by a household’s own sound and vision equipment. This extends the range of household production considered by Reid in 1934 and mostly since then by other writers. The expanded market alternative criterion would be ‘An activity shall be deemed productive if it is of such a character that it might be obtained by hiring a worker or by renting capital equipment from the market.’

Gilman and Reid had little impact on mainstream economics. Economic theory continued to portray households as places only of consumption and leisure, with production of goods and services occurring only in business or public enterprises.

3.2 The New Household Economics

In the mid-1960s a major theoretical development took place, known as the ‘new household economics’ (Becker 1981, Ironmonger 1972, Lancaster 1971). In this theory the household is regarded as a productive sector with household activities modeled as a series of industries.

In this new approach, households produce commodities that are designed to satisfy separate wants such as thirst, hunger, warmth, and shelter. The characteristics, or want-satisfying qualities, of the commodities used and produced can be regarded as defining the production and consumption technology of households. With changes in incomes and prices, households still alter expenditures as in the earlier theory. However, in the new theory, households adjust their behaviour as they discover new commodities and their usefulness in household production processes.

The activities approach derived from the theory of the new household economics readily combines with the earlier input-output approach of Leontief (1941) to establish a series of household input–output tables as the framework for modeling household production.

4. Measuring The Household Economy

The measurement of the household economy emerged as a focal point for many researchers once the household was recognized as a major centre of production, not just consumption.

4.1 Importance Of Measuring The Household Economy

In the 1970s a number of writers drew attention to the macroeconomic magnitude of the household economy. Boulding (1972) conceptualised households not only as the main driving force for the market economy, with household purchases covering about 60 percent of GNP, but also as the most important agent in the grants economy. This is the economy of one-way transfers, grants, or gifts, given mainly within households from those earning money incomes to other members, children, spouses, and dependants not earning a money income. Dependants receive clean, serviced accommodation, cooked meals, and clean clothes; the transfers are of transformed commodities purchased from the market which embody value added by household capital and labor.

In a perceptive book, The Household Economy, the American writer Scott Burns (1977) observed that ‘the hours of work done outside the money economy rival those done inside and will soon surpass them.’ Burns saw the household as the strongest and most important economic institution—healthy, stable, and growing. Alvin Toffler (1980) took a similar optimistic view of the household economy in his classic The Third Wave where he describes the many ways in which tasks are being driven back from the market to the household.

The pressure to transfer paid labor costs from the market to the unpaid labor costs of the household leads to the development of self-service petrol stations, automatic bank tellers, and Internet shopping. It also leads governments to support unpaid household-based care of sick, disabled, and elderly people instead of professional care in hospitals and nursing homes. Taxation of paid labor helps drive these technology and policy changes.

4.2 Deficiencies In The National Statistics Of Work And Production

During the latter half of the twentieth century an almost unrecognized statistical revolution took place. At its heart was the System of National Accounts (SNA) that provides the framework for estimating GDP. Governments now spend millions of dollars collecting and publishing regular quarterly statistics of GDP and of the numbers employed in this production. These data permit comparisons of economic performance through time and between countries.

Statistics of GDP and employment are not only the common discourse of economists but have been elevated universally as major tools of economic and social policy including those operating at the international level through the International Labour Office, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank.

In the 1980s a number of writers exposed the deficiencies in statistics of work and production. Among these are Luisella Goldschmidt-Clermont (1982) and Ann Chadeau (1985). Perhaps the most strongly advanced reason for measuring household production is to make women’s work visible as exemplified by Marilyn Waring’s books Counting for Nothing (1988) and Three Masquerades (1996). Throughout the world, women provide most of the labor needed in household and subsistence production. All of this work is unpaid. On the other hand, in spite of increasing participation of women in paid jobs, most paid work is still done by men.

With few exceptions, the national statistics of work and production continue to ignore the unpaid labor and economic output contributed by women (and men) through household production. At least twothirds of the work and economic production of women, half of the world’s adult population, is excluded. Discussion of public issues such as gender equality, labor market policies, wages, and income policies, to name a few, is statistically misinformed. The point is made frequently that the increase in women’s participation in paid work leads to overstatement of the increase in measured economic activity, because the reduction in household production is not counted (Nordhaus and Tobin 1973, Weinrobe 1974).

The SNA definitions used to measure production cover market transactions only. They exclude household production and make no allowance for the destruction of natural resources.

These omissions have been much criticized by the women’s and environmental movements. Consequently, the UN Statistical Commission, in the 1993 revision of the SNA, has recommended that national statistical offices prepare accounts for economic activities outside the presently defined production boundary. ‘Satellite’ accounts separate from, but consistent with, the main SNA accounts of the market economy can be prepared to show the use of natural resources or the extent of economic production by households.

Demands for the full recognition of women’s economic production culminated in the Platform for Action adopted in September 1995 at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. It enjoined ‘national, regional and international statistical services and relevant governmental and United Nations agencies’ to develop a more comprehensive knowledge of all forms of work and employment by:

Improving data collection on the unremunerated work which is already included in the United Nations System of National Accounts’ and developing methods for ‘assessing the values, in quantitative terms, of unremunerated work that is outside national accounts, such as caring for dependants and preparing food, for possible reflection in satellite or other official accounts (Platform For Action, Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing, 1995).

As statistics currently used to measure work and valuable production are incomplete and misleading, new measures are required to produce more accurate statistical pictures.

4.3 Methods Of Estimating The Household Economy

Some of the earliest estimates of the value of household services were those made for the United States (by Mitchell for 1919 and Kuznets for 1929) and for Sweden (by Lindahl, Dahlgren, and Korb for 1929 and earlier years); they simply multiplied the total number of households in rural and urban areas by the corresponding annual cost of hiring a domestic servant (Hawrylyshyn 1976).

The statistical offices of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden included household production in their national income estimates prior to World War II. Norway’s estimates, started in 1912, were quite elaborate, valuing the unpaid work of married women on average wage income for unmarried women and widows in various age groups. They were discontinued in 1950 when the United Nations recommendations were adopted (Aslaksen and Koren 1996).

The Scandinavian view that the real economic production of goods and services included all goods and services produced by households, whether for their own use or for others, was unable to prevail in the debates about the initial standards for national income and product accounting. The market-based approach to GDP estimates continues. However, the way is clear through satellite national household accounts for separate estimates to be made of the value of household production, Gross Household Product (GHP).

The initial information base for such estimates is provided by surveys of the use of time on various household activities (Vanek 1974). International comparability of statistics of the uses of time was given a great boost by the cross-national time budget study in 12 countries conducted in the 1960s under the sponsorship of UNESCO and the International Social Science Council (Szalai 1972). Since then national statistical offices in many OECD countries have followed the Szalai methodology collecting diary based national surveys of time use from representative samples of households.

The results show that the present statistics of employment greatly understate the volume of economic work needed. Surveys across 12 OECD countries covering various years from 1985 to 1992 show that the mean time spent in paid work was 24 h per adult per week. The mean average unpaid work in the household economy was 26 h per adult per week (Goldschmidt-Clermont and Pagnossin-Aligisakis 1995, Ironmonger 1995).

The representations of work provided by official statistics of employment are thus at variance with those from official statistics of work from time use surveys. In the main, official statisticians still report an outmoded view that unpaid domestic work is somehow not ‘work’—only those working in the monetized market sector are counted as being ‘economically active.’

Three methods of imputing a value to the time used in household production have been used, all taking a wage per hour from the market economy. The first is the ‘opportunity cost’ wage that a person could be paid for doing an extra hour of work in a market job rather than an hour of unpaid household work. The cost of an hour of household work is the forgone opportunity to earn in the market. This method is usually rejected since it yields different values depending on who performed the task. The second method uses the wages of specialist paid workers who come to the household, e.g., a cleaner, a cook, a nanny, a gardener, to value the same tasks performed by household members. This ‘specialist replacement cost’ method can be criticized because these workers work more efficiently than a usual household member can, taking less time to perform the same task. Finally, a ‘generalist replacement cost’ method of valuation uses the wage rate for a generalist worker or housekeeper. This is regarded as more appropriate since the working conditions and range of activities are similar to those of household members.

Time-use surveys provide only one source of information about household production since they omit the contribution from nonhuman capital (the land, dwellings, and equipment owned by households). A more complete national accounting approach to measuring and modeling the household economy is required to cover all factors of household production, all intermediate inputs, and all the principal outputs.

5. National Household Accounts And Modeling The Household Economy

5.1 Extended National Accounts

A number of scholars have suggested that national accounts needed extending to cover missing nonmarket household production. Essentially, they viewed household production as a missing part of the estimates, not a separate economy. Robert Eisner and co-workers at Northwestern University conducted the most extensive work on these lines in the 1980s. Their research culminated in the book The Total Incomes System of Accounts (1989). Eisner’s estimates for the United States make clear the greatly expanded role, in total economic product, of households. United States GHP in 1981 was put at $1709 billion, 37.5 percent of the extended GNP of $4560 billion.

5.2 Household Input–Output Tables And Satellite Household Accounts

Household production is best considered as the production of goods and services by a separate economy, complementary to and competitive with the market economy. Every country can be analyzed as two linked economies. The household sells labor to the market; it uses the money income to purchase intermediate commodities from the market which it transforms into items of final consumption through the use of its own unpaid labor and its own capital goods.

The household economy can be studied as a set of six industries providing accommodation, meals, clean clothes, transport, recreation, and care in competition with parallel market industries. Activities such as shopping and cleaning are simply ancillary activities to the principal final outputs of the household economy. The input–output approach to measuring and modeling the industries of the market economy associated with the work of Leontief (1941) has been applied to measuring and modeling the industries of the household economy. This was started in Australia for Australian households (Ironmonger 1989). Input– output tables showing the uses of labor, capital, energy, and materials in each of the main and ancillary industries of the household economy have now been prepared for Australia, Canada, Finland, Norway, and the United States.

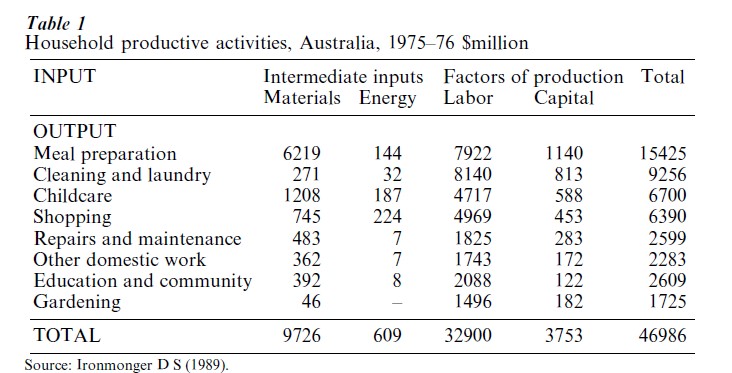

How the household economy uses time, materials, energy, and capital can be seen from the Table 1 adapted from the first published household input– output table. This is for the Australian household economy. The household input–output tables are exactly the satellite accounts that have been recommended in the 1993 revision of the SNA and in the resolution of the Platform for Action of the 1995 Beijing Women’s Conference. The world statistical agencies need to establish standardized methods of estimating GHP.

6. Household Production And A World Of Binary Economies

The major scientific achievement of this field has been the measurement of the magnitude of household production through surveys of the uses of time. Household production is now recognized as an alternative economy to the market; in many countries the household economy absorbs more labor and at least one-third the physical capital used in the market economy.

In future, national statistical organizations will produce regular estimates of GHP. Data on outputs of household production—accommodation, meals, clean clothes, and the care of children and adults—will complement data on inputs of unpaid labor and the use of household capital.

Proper recognition of the household economy will have arrived when national household accounts are published each quarter alongside national accounts for the market economy. These data will enable greater scientific research on the organization of household production, the interactions with the market economy, the role of households in building human capital, on the effects of household technology, alternative social and economic policies on gender divisions of labor, and on family welfare.

Bibliography:

- Aslaksen I, Koren C 1996 Unpaid household work and the distribution of extended income: the Norwegian experience. Feminist Economics 2(3): 65–80

- Becker G S 1981 A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Boulding K 1972 The household as Achilles’ Heel. Journal of Consumer Affairs 6(2): 110–19

- Chadeau A 1985 Measuring household activities: some international comparisons. Review of Income and Wealth 3: 237–53

- Eisner R 1989 The Total Incomes System of Accounts. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Goldschmidt-Clermont L 1982 Unpaid Work in the Household: A Review of Economic Evaluation Methods. International Labour Office, Geneva, Switzerland

- Goldschmidt-Clermont L, Pagnossin-Aligisakis E 1995 Measures of unrecorded economic activities in fourteen countries. Human Development Report Office Occasional Papers 20, United Nations Development Programme, New York

- Hawrylyshyn O 1976 The value of household services: a survey of empirical estimates. Review of Income and Wealth 22: 101–31

- Ironmonger D S 1972 New Commodities and Consumer Behaviour. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Ironmonger D S 1989 Research on the household economy. In: Ironmonger D (ed.) Households Work. Allen & Unwin, Sydney, Australia

- Ironmonger D S 1995 Modeling the household economy. In: Dutta M (ed.) Economics, Econometrics and The LINK: Essays in Honor of Lawrence R Klein. Elsevier, Amsterdam

- Ironmonger D S 1996 Counting outputs, capital inputs and caring labor: estimating gross household product. Feminist Economics 2(3): 37–64

- Lancaster K 1971 Consumer Demand: A New Approach. Columbia University Press, New York

- Leontief W W 1941 The Structure of the American Economy, 1919–1939. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Nordhaus W D, Tobin J 1973 Is growth obsolete? In: Moss M (ed.) The Measurement of Economic and Social Performance. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York

- Reid M G 1934 Economics of Household Productions. Wiley, New York

- Szalai A 1972 The Uses of Time: Daily Activities and Suburban Populations in Twelve Countries. Mouton, The Hague, The Netherlands

- Vanek J 1974 Time spent in housework. Scientific American 231: 116–20

- Weinrobe M 1974 Household production and national production: an improvement of the record. Review of Income and Wealth 20: 89–102