Sample Economics Of Education Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The economics of education is conceptually very broad. It could logically cover all aspects of the demand for schooling and of the impacts of schooling on subsequent outcomes. This discussion, however, concentrates on the more limited range of issues related to the organization, funding, and performance of schools.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Many facets of the broader field overlap those of labor economics, public finance, and growth theory, and they can best be put into those contexts—leaving this discussion to the unique facets of schools. The economics of education also borrows from other disciplines such as sociology and psychology, but the underlying behavior perspective remains unique to economics.

The economics of education is naturally linked to the study of human capital. Human capital refers to the skills and productive capacity embodied in individuals. While implicitly part of economics for several centuries (Kiker 1968), this idea has recently developed into a central concept in both theoretical and empirical analyses with the foundational work of T. W. Shultz (1961), Gary Becker (1993 [1964]), and Jacob Mincer (1970, 1974). Nonetheless, while abstractly dealing with skills and capabilities of individuals, human capital—to be both predictive and testable—must be defined in terms of more concrete measures. This requirement most often brings up schooling as a clear, measurable aspect of human capital that can proxy for major skill differences. While an expansive view could include all research topics that touch on schooling, it is useful to define the economics of education more narrowly in terms of unique aspects not covered in other subdisciplines: namely, the education sector itself. This discussion is also limited by available data and analyses. Due to a dearth of reliable outcome data from higher education as well as schools in other countries, the economics of education has concentrated its study largely on American K-12 schools. (The study of the economics of higher education, largely lacking student performance information, has directed most attention to issues of access and attendance and particularly of the influence of financial aids and costs on these (see for example McPherson and Schapiro 1990 or Kane 1994). Because these analyses have such a different perspective from those related to primary and secondary education, they are not included in this discussion.)

1. Outcomes

It is natural for economists to think in terms of a production model where certain factors and influences go in, and products of interest come out. This model, called the ‘production function’ or ‘input–output’ approach, is the model behind much of the analysis in the economics of education. The measurable inputs are things like school resources, teacher quality, and family attributes, and the outcome is student achievement. Let us focus on the outcome, first, and then move on to inputs, where more controversy exists.

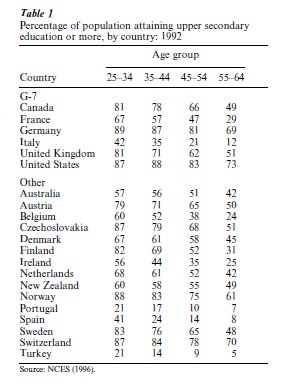

Historically, the most frequently employed measure of schooling has been attainment, or simply years of schooling completed. The United States leads the world in investing in schooling. By the mid-1970s, three-quarters of US students completed high school, culminating a long national investment period that started with just 6 percent graduating from high school at the turn of the century. Many developed and developing countries, however, have recently mimicked this trend, as illustrated in Table 1, which displays the increasing completion of secondary schooling for more recent age cohorts. By tracing schooling across different age groups, the growth in attainment is readily seen. The value of school attainment as a rough measure of individual skill has been verified by a wide variety of studies of labor market outcomes. In the US, Mincer (1974) pioneered the approach that is now standard. Psacharopoulus (1985) has taken this analysis to the rest of the world. The estimation considers the relationship between earnings (viewed as a direct measure of individual productivity) and schooling and labor market experience.

However the difficulty with this common measure of outcomes is that it assumes a year of schooling produces the same amount of student achievement over time and in every country. This measure simply counts the time spent in schools without judging what happens in schools—thus, it does not provide a complete or accurate picture of outcomes. Today, more attention is focused on quality outcomes, and the most common measure is tests for cognitive skills. To the extent that the productive value of schooling largely involves the ability to make decisions under uncertainty and to adapt to new ideas and technologies (cf. Nelson and Phelps 1966, Welch 1970), cognitive skills appear to be a valid measure of human capital. This conclusion is supported by recent studies that show a direct correlation between test scores and earnings in the labor market.

While early studies of wage determination indicated relatively modest impacts of variations in cognitive ability after holding constant quantity of schooling, more recent direct investigations of cognitive achievement find generally larger labor market returns to measured individual differences in cognitive achievement (e.g., Bishop 1989, 1991, O’Neill 1990, Grogger and Eide 1993, and Murnane et al. 1995). (A parallel line of research has employed school inputs to measure quality, but, while some controversy exists, this has not been as successful. Specifically, school input measures have not proved to be good predictors of wage or growth. The strategy faces the measurement problems discussed below and ignores the fact that families, peers, and individual ability also enter into the equation.) Similarly, society appears to gain in terms of productivity; Hanushek and Kimko (2000) demonstrate that quality differences in schools have a dramatic impact on productivity and national growth rates.

Attention to quality and cognitive skills also matches a growing policy interest. As countries have moved toward more universal access to schooling, they have turned to issues of quality of publicly provided schooling.

2. Production

Let us now look at the other side of the education equation—the inputs, or determinants, of student achievement. Because outcomes cannot be changed by fiat, much attention has been directed at inputs—particularly those perceived to be relevant for policy such as school resources or aspects of teachers.

(This is differentiated from the more common approach in educational research of ‘process-outcome’ studies where attention rests on the organization of the curriculum, the methods of presenting materials, the interactions of students, teachers and administrators, and the like. An entirely different approach–true experimentation–has been much less frequently applied, particularly when investigating the effects of expenditure differences. The best known is an experiment in class size reduction in the United States during the mid-1980s, Project STAR (Word et al. 1990).) ‘Analysis of the role of school resources in determining achievement begins with the ‘Coleman Report,’ the US government’s monumental study on educational opportunity released in 1966 (Coleman et al. 1966). The report was conducted in compliance with a mandate of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to investigate the extent of inequality in the nation’s schools. Although this was not the first such effort, it was much larger and much more influential than any previous (or subsequent) study.

The study’s greatest contribution was directing attention to the distribution of student performance—the outputs as opposed to the inputs. Instead of addressing questions of inequality by simply listing an inventory of differences of schools and teachers by race and region, it highlighted the relationship between inputs and outputs of schools.

Unfortunately most of the attention the report generated focused on the report’s conclusions rather than its innovative perspective. The controversial conclusion was that schools are not very important in determining student achievement; on the contrary, families and, to a lesser extent, peers are the primary determinants of performance variance. The findings immediately led to a large (but decentralized) research effort to compile additional evidence about input– output relationships in schools (There were also extensive analyses of the report’s methodology and of the validity of its inferences. See, for example, Bowles and Levin (1968), Cain and Watts (1970), and Hanushek and Kain (1972).)

The underlying model that evolved as a result of this research is very straightforward. The output of the educational process, that is, the achievement of individual students, is directly related to a series of inputs. Some of these inputs—the characteristics of schools, teachers, curricula, and so forth—are directly controlled by policy makers. Other inputs—those of families and friends plus the innate endowments or learning capacities of the students—are generally not controlled. Further, while achievement may be measured at discrete points in time, the educational process is cumulative; inputs applied sometime in the past affect students’ current levels of achievement.

The selected input measures have been fairly similar across studies. Family background is usually characterized by such sociodemographic characteristics as parental education, income, and family size. Peer inputs, when included, are typically totals of a student population’s sociodemographic characteristics for a school or classroom. School inputs include teacher background (education level, experience, sex, race, and so forth), school organization (class sizes, facilities, administrative expenditures, and so forth), and district or community factors (for example, average expenditure levels). Except for the original Coleman Report, most empirical work has relied on data constructed for other purposes, such as a school’s standard administrative records. (As discussed elsewhere (Hanushek 1979, 1986), a variety of empirical problems enter into the estimation and the subsequent interpretation of results. The most significant general problems are the lack of measurement of innate abilities of individuals and the imprecise measurement of the history of educational inputs. Both the quality of the data and the estimation techniques are very important in interpreting specific findings, but, as discussed below, these findings have less impact on the aggregate findings illuminated here.) Based on this, statistical analysis (typically some form of regression analysis) is employed to infer what specifically determines achievement and what is the importance of the various inputs into student performance.

3. The Importance Of Measured School Inputs

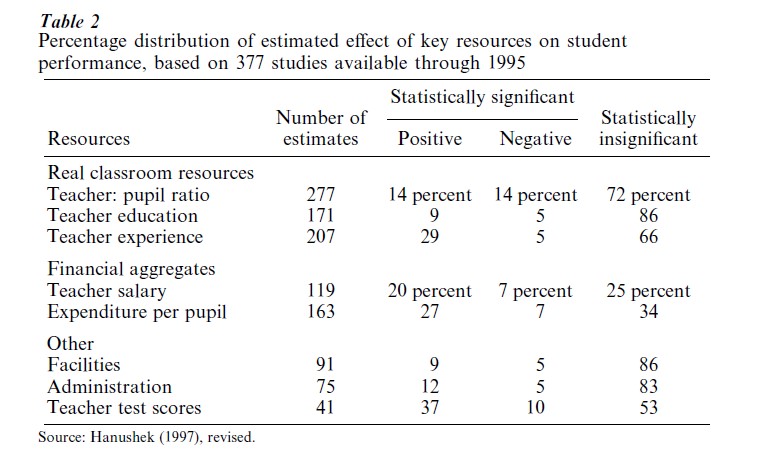

The state of knowledge about the impacts of resources is best summarized by reviewing available empirical studies. Most analyses of education production functions have directed their attention at a relatively small set of resource measures, and this makes it easy to summarize the results (Hanushek 1997). Table 2 provides a tabulation of estimates of the impact of school inputs. The 90 individual publications that appeared before 1995 and that form the basis for this analysis contain 377 separate production function estimates. The table indicates the sign of the estimated impact of a given resource on student performance; positive estimates imply that more resources are associated with higher student outcomes and the opposite for negative estimates. Additionally, information is provided about statistical significance, or our confidence that there is a real effect of the resources.

For classroom resources, only 9 percent of studies on teacher education and 14 percent of studies on teacher–pupil ratios found a positive and statistically significant relationship between these factors and student performance. (This summary concentrates on the results. Details of the underlying analyses and the selection of studies for this tabulation are found in Hanushek (1986, 1997). The first column provides a count of the total number of estimates addressing the impact of the given resource.) Moreover, these studies were offset by another set of studies that found a similarly negative correlation between those inputs and student achievement. Twenty-nine percent of the studies found a positive correlation between teacher experience and student performance; however, 71 percent still provided no support for increasing teacher experience (being either negative or statistically insignificant).

Studies on the effect of financial resources provide a similar picture. There is very weak support for the notion that simply providing higher teacher salaries or greater overall spending will lead to improved student performance. Per pupil expenditure has received the most attention, but only 27 percent of studies showed a positive and significant effect. In fact, 7 percent even suggested that adding resources would harm student achievement. It is also important to note that studies involving pupil spending have tended to be the lowest quality studies, and thus there is substantial reason to believe that even the 27 percent figure overstates the true effect of added expenditure.

4. Do Teachers And Schools Matter?

Because of the Coleman Report and subsequent studies discussed above, many have argued that schools do not matter, and that only families and peers affect performance. Unfortunately, these interpretations have confused measurability with true effects.

Extensive research since the mid-1960s has made it clear that teachers do indeed matter. The simple definition of teacher quality used here is an output measure based on student performance, instead of the more typical input measures based on characteristics of the teacher and school. High-quality teachers are ones who consistently obtain higher than expected gains in student performance, while low quality teachers are ones who consistently obtain lower than expected gains. When this approach has been used, large variations in performance have been uncovered.

In fact, the degree to which teacher differences affect performance is impressive. Looking at the range of quality for teachers within a single large urban district, teachers near the top of the quality distribution can get an entire year’s worth of additional learning out of their students compared to those near the bottom (Hanushek 1992).

If teacher quality is central to the performance of schools, then research and policy quite naturally should focus on this. Unfortunately, it has been difficult to link quality—measured by impacts on student achievement—to labor markets. While considerable work has been done to assess the gross flows of individuals into teaching and how those are affected by economic conditions, this does not provide a reliable link to quality. Murnane et al. (1991),

Hanushek and Pace (1995), and Ballou and Podgursky (1997) show how various characteristics of teachers including test scores and quality of college are related to labor market conditions and school choices in the United States. Similarly, Hanushek and Rivkin (1997) for the US and Dolton and van der Klaauw (1995) for the UK find that teacher supply adjusts to salaries and labor markets. Nonetheless, these leave open the essential concern about any systematic impacts on school performance. Accurate assessment of teacher labor markets requires reliable quality measures along with information about hiring, retention, and mobility of teachers, and such data have not been available.

5. Study Quality

The previous discussions do not distinguish among studies on the basis of any quality differences, so the results could be distorted by not adjusting the tabulations. While ‘study quality’ has a variety of subjective components, the available estimates can be separated by a few objective components of quality. First, while education is cumulative, frequently only current input measures are available, which results in analytical errors. Second, schools operate within a policy environment set almost always at higher levels of government. In the United States, state governments establish curricula, provide sources of funding, govern labor laws, determine rules for the certification and hiring of teachers, and the like. In other parts of the world, similar policy setting, frequently at the national level, affects the operations of schools. If these attributes are important—as much policy debate would suggest—they must be incorporated into any analysis of performance, but little progress has been made in identifying or measuring the relevant aspects of policy. Each of these problems potentially leads to biases in the estimated effects of educational inputs. The adequacy of dealing with these problems is a simple index of study quality.

The details of these quality issues and approaches for dealing with them are discussed in detail elsewhere (Hanushek 1997) and only summarized here. The first problem is ameliorated if one uses the ‘value added’ vs. ‘level’ form in estimation. That is, if the achievement relationship holds at different points in time, it is possible to concentrate on the growth in achievement and on exactly what happens educationally between those points when outcomes are measured. This approach largely eliminates prior inputs of schools and families, which will be incorporated in the initial achievement levels that are measured (Hanushek 1979). The latter problem of imprecise measurement of the policy environment can frequently be ameliorated by studying performance of schools operating within a consistent set of policies—e.g., within states in the US or similar decision making spheres elsewhere. Because all schools within a state operate within the same basic policy environment, comparisons of their performance are not strongly affected by unmeasured policies (Hanushek and Rivkin 1997). If the available studies are divided by whether or not they deal with these major quality issues, the prior conclusions about research usage are unchanged (Hanushek 1997).

An additional issue, which is particularly important for policy purposes, concerns whether this analytical approach accurately assesses the causal relationship between resources and performance. If, for example, school decision makers provide more resources to those they judge as most needy, higher resources could simply signal students known for having lower achievement. In such a case, the statistical results might reflect the impact of achievement on resources, instead of the other way around. One way to deal with this is to take into account explicitly the resource allocation process. When done in the case of class sizes, the evidence has been mixed (cf. Angrist and Lavy 1999, Hoxby 2000, Rivkin et al. 2000). An alternative involves the use of random assignment experimentation rather than statistical analysis to break the influence of sample selection and other possible omitted factors. The benefits of this approach are well demonstrated in other fields (e.g., medicine or agriculture). By randomizing who gets the treatment and comparing outcomes across treatment and control groups, it is less likely than is the case in standard statistical analyses that problems of model misspecification or of selection into treatment situations will bias the estimates of program effects. With one major exception, this approach nonetheless has not been applied to understand the impact of schools on student performance. The exception is Project STAR, an experimental reduction in class sizes that was conducted in the State of Tennessee in the mid-1980s (Word et al. 1990). To date, it has not had much impact on research or our state of knowledge. (While Project STAR has entered a number of policy debates, the results remain controversial (Krueger 1999, Hanushek 1999).)

6. Investigations Outside The United States

Researchers have conducted studies on student performance around the world, although with lower frequency. Because student performance data are much less readily available outside the US, most such studies have been special purpose studies that are frequently difficult to generalize. Nonetheless, the results appear qualitatively very similar.

In less developed countries, there is a slightly stronger correlation between resources and achievement, but the overall picture remains the same (Hanushek 1995). This similarity is surprising, because one might expect more impact of resources in schools that begin with very low levels of resources.

For developed countries, the evidence is even scarcer and more difficult to summarize. A review by Vignoles et al. (2000) points to a small number of studies outside the US and shows variation in results similar to that reported elsewhere. Nonetheless, the limited research makes any generalizations difficult.

7. Efficiency

Efficiency involves the relationship between inputs and outputs in a production process. The underlying notion is that production is efficient if given inputs produce the maximum output. The simplicity of this statement, however, obscures a variety of complexities that arise when the concept is actually applied.

Typically, economics does not devote much attention to the analysis of efficiency. If there are competitive markets, the behavior of producers and consumers tends to drive outcomes toward efficient production. Because of this basic theorem, it is common simply to assume efficiency.

In education, however, efficiency is never a given. First, education is generally publicly provided. Governmental organizations, which do not face the same incentives as private firms, cannot be expected to move toward efficient production. In particular, few school personnel are rewarded or punished based on the outcomes students obtain, making the incentives for performance minimal or nonexistent. Second, it is difficult to find information on school efficiency. With complete information, parents might be expected to pressure schools to use resources more efficiently— either through local political processes or through moving to districts that did better (Tiebout 1956). Because student performance is influenced by factors schools can’t control—i.e., input from family and friends—simply observing student achievement does not accurately reflect school contribution. Thus, parental and voter pressures on schools are lessened by imperfect information.

The underlying political economy of schools that can preserve such apparently large inefficiencies in resource use deserves considerably more research.

8. Competition And Incentives

The lack of direct incentives within schools has led to investigations of circumstances where incentive forces may be stronger. While there have been a wide variety of proposed changes (e.g., Hanushek et al. 1994), most have not been implemented or analyzed sufficiently to draw any conclusions about their efficacy.

The classic argument for competition comes from Friedman (1962) with his arguments for vouchers. The well-known arguments suggest that separating the finance of schooling from the production of schooling by allowing students to choose the school they attend would improve individual satisfaction with the outcomes. Within the United States, this approach has been vigorously debated, but few examples of implementation have occurred.

The most celebrated application has been Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where vouchers have been available to a (constrained) number of poor children since 1990 (Witte 1999). A number of privately financed alternatives have also been offered (Howell et al. 2000). Most of the attention to these voucher programs has centered on the student outcomes of students in them compared to public schools. (A variety of controversies have developed in these analyses. Perhaps the primary analytical issue is dealing with a selection of students and an appropriate comparison group. See, for example, the discussions in Witte (1999), Rouse (1998), and Greene et al. 1998).) Because these programs have been very marginal to the education system, there has been little suggestion that the public schools have made any adjustments in response. Thus, these choice experiences have not provided information about how public schools might react to a larger, more institutionalized program.

Private schools offer one possibility for better understanding the effects of competition. They must compete with the public schools in order to attract clients, and thus they are subject to stronger pressures to provide high levels of performance. The literature on Catholic school performance is summarized in Neal (1998) and Grogger and Neal (2000). The evidence has generally indicated that Catholic schools on average outperform public. This superiority seems clearest in urban settings, where disadvantaged students face fewer options than others. This evidence is, nonetheless, subject to some caveats. First, as recognized since some of the earliest work on the topic (Coleman et al. 1982), it is difficult to separate performance of the private schools from pure selection phenomena. Specifically, since private school students could have attended public schools but instead pay extra for private schooling, they are clearly different than the public school students with identical measured characteristics. A variety of alternative approaches have been taken to deal with the selection problem, and a rough summary of the results after those efforts is that there remains a small advantage from attending Catholic schools. (Grogger and Neal (2000) suggest, however, that there is no advantage to attending private elite schools—a surprising result given the extra cost usually involved in that. These results are possibly due to selection problems, but it not a simple relationship because most people would expect positive selection into these elite schools.) Second, this literature says little about the distribution of school quality within the Catholic sector. Within the public sector, it is widely believed that school quality varies considerably across schools, and one might suspect that the same holds true for private schools.

A related issue is the reactions of public schools to the private sector. Hoxby (1994) demonstrates that public schools in areas that have larger concentrations of Catholic schools perform better than those facing less private competition. This analysis provides the first consistent evidence suggesting that public schools react to outside competition.

Perhaps the most important potential element competition comes from other public school jurisdictions. Specifically, households can choose the specific jurisdiction and school district, a la Tiebout (1956), by their choice of residential location. While adjustment is costly, these choices permit individuals to seek high-quality schools if they wish. Residential location decisions are of course complicated, involving job locations, availability of various kinds of housing, school costs and quality, and availability of other governmental services. Given choice opportunities plus voting responses, this model suggests pressure on schools to use resources effectively. Otherwise one might expect housing values to be affected.

The simple choice model would suggest naturally that larger numbers of schools or school districts per student would offer more opportunities for residents and thus more competition across schools. This simple model motivates the empirical analyses of Borland and Howsen (1992) and its extension and refinement in Hoxby (2000) and in Hanushek and Rivkin (forthcoming). The simple inclusion of measures of concentration indicates that areas with less choice have poorer schools on average (Borland and Howsen 1992). Hoxby (2000) pursues alternative strategies to look at the causal impact of concentrations and finds a larger estimated impact of competition on the performance of schools. Similarly, Hanushek and Rivkin (forthcoming) find competitive impacts on performance of urban schools and that these are particularly important for low income students who have fewer mobility options.

9. Finance Of Schools

Public finance economists have devoted considerable energy to the study of the finance of schools, largely from the viewpoint of traditional tax and expenditure policy. The educational policy component of this involves equity in the provision of education. These considerations are largely motivated by the many studies that show wide disparities in achievement by race and socioeconomic background (e.g., Coleman et al. 1966, Hanushek 2001). Nonetheless, the typical discussion of equity concentrates primarily on spending disparities across schools and districts.

Indeed, one of the most significant policy issues since the early 1970s in the United States has been the appropriate way for states to fund local schools. While most states have employed a compensatory aid formula to ameliorate some local governments’ difficulty in raising taxes, these measures have only partially solved the problem. The issue became the subject of court action in the 1960s, with the case of Serrano s. Priest in California. Suits in many other states followed. As a result, some significant narrowing of spending variations occurred (Murray et al. 1998).

However there has been surprisingly little analysis of the impacts of these suits. This is important to undertake, because the prior research discussed above does not show a clear link between increased funding and school quality or student performance. From the perspective of educational outcomes, then, the value of spending changes related to equalization court cases and the related legislative actions remains an open question (Hanushek 1991). To date, little research has focused on the achievement impacts of school finance policies. The one analysis of the impact of the Serrano case found no lessening of variation in student outcomes after spending was equalized across districts (Downes 1992). A broader, nationwide analysis of district spending on earnings outcomes also found no beneficial relationship between the two, except perhaps for black females (Hanushek and Somers 2001).

10. Some Conclusions And Implications

The existing research suggests inefficiency in the provision of schooling. It does not indicate that schools do not matter. Nor does it indicate that money and resources never impact achievement. The accumulated research simply says there is no clear, systematic relationship between resources and student outcomes. The persistence of this raises important questions about current education policy, as well as a real need for further research.

The main conclusion of this research is that policy decisions should not focus on school resources, because the impact of resources on student achievement is unknown at this time. The policy solution seems to be to establish incentives—rewards or consequences related to student outcomes—and then to permit local schools to develop their own game plans for meeting these goals. While a wide variety of incentives have been proposed—such as vouchers, merit pay, or contracting out—most have not been implemented or analyzed sufficiently to determine their efficacy.

A final major issue raised by these analyses is their implication for other kinds of studies (Hanushek 1996). Most studies involving human capital are interested in its effect on other aspects of behavior. For these studies schooling is largely tangential to other interests, and researchers are typically simply looking for an easy and readily available measure of school quality. The most common has been spending per pupil. However, the inefficient production of human capital introduces natural measurement problems. Direct spending is no longer a good measure of quality because it has no perceivable bearing on performance. Second, it is well known that families have considerable influence on student achievement, implying that school resources are only part of the equation. Both factors suggest that studies which measure student achievement just through resource investment have a high potential for distortion.

Bibliography:

- Angrist J D, Lavy V 1999 Using Maimondides’ rule to estimate the effect of class size on scholastic achievement. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114: 533–75

- Ballou D, Podgursky M 1997 Teacher Pay and Teacher Quality. W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Kalamazoo, MI

- Becker G 1993 Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, 3rd edn. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Bishop J H 1989 Is the test score decline responsible for the productivity growth decline? American Economic Review 79: 178–97

- Bishop J 1991 Achievement, test scores, and relative wages. In: Kosters M H (ed.) Workers and their Wages. The AEI Press, Washington, DC, pp. 146–86

- Borland M V, Howsen R M 1992 Student academic achievement and the degree of market concentration in education. Economics of Education Review 11: 31–9

- Bowles S, Levin H M 1968 The determinants of scholastic achievement–an appraisal of some recent evidence. Journal of Human Resources 3: 3–24

- Cain G G, Watts H W 1970 Problems in making policy inferences from the Coleman Report. American Sociological Review 35: 328–52

- Coleman J S, Campbell E Q, Hobson C J, McPartland J, Mood A M, Weinfeld F D, York R L 1966 Equality of Educational Opportunity. US Department of Health, US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

- Coleman J S, Hoffer T, Kilgore S 1982 High School Achievement: Public, Catholic and Private Schools Compared. Basic Books, New York

- Dolton P, van der Klaauw W 1995 Leaving teaching in the UK: A duration analysis. The Economic Journal 105: 431–44

- Downes T A 1992 Evaluating the impact of school finance reform on the provision of public education: The California case. National Tax Journal 45: 405–19

- Friedman M 1962 Capitalism and Freedom. University of Chicago, Chicago

- Greene J P, Peterson P E, Du J 1998 School choice in Milwaukee: A randomized experiment. In: Peterson P E, Hassel B C (eds.) Learning from School Choice. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, pp. 335–56

- Grogger J T, Eide E 1995 Changes in college skills and the rise in the college wage premium. Journal of Human Resources 30: 280–310

- Grogger J T, Neal D 2000 Further evidence on the effects of Catholic secondary schooling. In: Gale W G, Rothenberg Pack J (eds.) Brookings–Wharton Papers on Urban Affairs, 2000. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp. 151–93

- Hanushek E A 1979 Conceptual and empirical issues in the estimation of educational production functions. Journal of Human Resources 14: 351–88

- Hanushek E A 1986 The economics of schooling: Production and efficiency in public schools. Journal of Economic Literature 24: 1141–77

- Hanushek E A 1991 When school finance ‘reform’ may not be good policy. Harvard Journal on Legislation 28(Summer): 423–56

- Hanushek E A 1992 The trade-off between child quantity and quality. Journal of Political Economy 100: 84–117

- Hanushek E A 1995 Interpreting recent research on schooling in developing countries. World Bank Research Observer 10: 227–46

- Hanushek E A 1996 Measuring investment in education. Journal of Economic Perspectives 10(Fall): 9–30

- Hanushek E A 1997 Assessing the effects of school resources on student performance: An update. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 19: 141–64

- Hanushek E A 1999 Some findings from an independent investigation of the Tennessee STAR experiment and from other investigations of class size eff Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 21: 143–63

- Hanushek E A 2001 Black–white achievement differences and governmental interventions. American Economic Review 91: 24–8

- Hanushek E A, Kain J F 1972 On the value of ‘equality of educational opportunity’ as a guide to public policy. In: Mosteller F, Moynihan D P (eds.) On Equality of Educational Opportunity. Random House, New York, pp. 116–45

- Hanushek E A, Kimko D D 2000 Schooling, labor force quality, and the growth of nations. American Economic Review 90: 1184–208

- Hanushek E A, Pace R R 1995 Who chooses to teach (and why)? Economics of Education Review 14: 101–17

- Hanushek E A, Rivkin G forthcoming Does public school competition affect teacher quality? In: Hoxby C M (ed.) The Economics of School Choice. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Hanushek E A, Rivkin S G 1997 Understanding the twentieth-century growth in U.S. school spending. Journal of Human Resources 32: 35–68

- Hanushek E A, Somers J A 2001 Schooling, inequality, and the impact of government. In: Welch F (ed.) The Causes and Consequences of Increasing Inequality. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Hanushek E A et al. 1994 Making Schools Work: Improving Performance and Controlling Costs. Brookings Institution, Washington, DC

- Howell W G, Wolf P J, Peterson P E, Campbell D E 2000 Testscore effects of school vouchers in Dayton, Ohio, New York

- City, and Washington, DC. Evidence from randomized field trials. In: Paper Prepared for the Annual Meetings of the American Political Science Association, Washington, DC

- Hoxby C M 1994 Do private schools provide competition for public schools? National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. 4978

- Hoxby C M 2000 The effects of class size on student achievement: New evidence from population variation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 115: 1239–85

- Kane T 1994 College entry by blacks since 1970: The role of college costs, family background, and the returns to education. Journal of Political Economy 102: 878–911

- Kiker B F 1968 Human Capital: In Retrospect. University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC

- Krueger A B 1999 Experimental estimates of education production functions. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114: 497–532

- McPherson M S, Schapiro M O 1990 Keeping college affordable: Government’s role in promoting educational opportunity. August

- Mincer J 1970 The distribution of labor incomes: A survey with special reference to the human capital approach. Journal of Economic Literature 8: 1–26

- Mincer J 1974 Schooling Experience and Earnings. NBER, New York

- Murnane R J, Singer J D, Willett J B, Kemple J J, Olsen R J 1991 Who Will Teach? Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Murnane R J, Willett J B, Levy F 1995 The growing importance of cognitive skills in wage determination. Review of Economics and Statistics 77: 251–66

- Murray S E, Evans W N, Schwab R M 1998 Education-finance reform and the distribution of education resources. American Economic Review 88: 789–812

- Neal D 1998 What have we learned about the benefits of private schooling? FRBNY Economic Policy Review 4(March): 79–86

- Nelson R R, Phelps E 1966 Investment in humans, technology diffusion and economic growth. American Economic Review 56: 69–75

- O’Neill J 1990 The role of human capital in earnings differences between black and white men. Journal of Economic Perspectives 4(Fall): 25–46

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development 1996 Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators. OECD, Paris

- Psacharopoulos G 1985 Returns to education: A further international update and implications. Journal of Human Resources 20: 583–604

- Rivkin S G, Hanushek E A, Kain J F 2000 Teachers, schools, and academic achievement. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 6691 (revised)

- Rouse C E 1998 Private school vouchers and student achievement: An evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program. Quarterly Journal of Economics 113: 553–602

- Schultz T W 1961 Investment in human capital. American Economic Review 51: 1–17

- Tiebout C M 1956 A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy 64: 416–24

- Vignoles A, Levacic R, Walker J, Machin S, Reynolds D 2000 The relationship between resource allocation and pupil attainment: A review. Research report No. 228, Department for Education and Employment, UK

- Welch F 1970 Education in production. Journal of Political Economy 78: 35–59

- Witte J F Jr 2000 The Market Approach to Education. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Word E, Johnston J, Bain H P, DeWayne Fulton B, Boyd Zaharies J, Nannette Lintz M, Achilles C M, Folger J, Breda C 1990 Student Teacher Achievement Ratio (STAR), Tennessee’s K-3 Class Size Study: Final Summary Report, 1985–1990. Tennessee State Department of Education, Nashville, TN