View sample economics research paper on public choice. Browse economics research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Public choice economics is the intersection of economics and politics. It uses the tools of economics to examine collective decisions. Public choice economics reflects three main elements: (1) methodological individualism, in which decision making occurs only with individuals; (2) rational choice, in which individuals make decisions by weighing the costs and benefits and choosing the action with the greatest net benefit; and (3) political exchange, in which political markets operate like private markets, with individuals making exchanges that are mutually beneficial (Buchanan, 2003). It is this last element that makes public choice a distinct field of economics.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Using the basic tools and assumptions of economics on collective decisions provides many insights. Economists assume that individuals are rationally self-interested in private decision making. However, this assumption is not always applied to the realm of collective decision making. In fact, for the first half of the twentieth century, it was argued that collective choices are made based on what is best for society. This view is referred to as public interest theory. Early public choice scholars called this dichotomy of behavior into question, arguing that individuals are rationally self-interested regardless of which sector they operate in. The public interest theory does not allow for someone operating in the public sector to make decisions based on what would benefit solely him or her. However, the public choice theory, properly understood, does acknowledge that when an actor in the public sector acts in his or her own self-interest, it may be consistent with the public’s interest. In this regard, the public choice view is a more encompassing theory.

Assuming that individuals are rationally self-interested and applying the laws of supply and demand provides a unique understanding of political decision making. (For the purposes of this research paper, the terms political and collective decision making are used interchangeably.) Voters can be thought of as demanders or consumers of public policy; as such, they are concerned with having policies enacted that will benefit them. Politicians act as suppliers of public policy. Just as businesses in the private sector compete for consumers, politicians compete for voters. If businesses want to maximize profits, then politicians want to maximize votes. Unlike in private markets, public sector decision making has a third party involved in the decision making process: bureaucrats or civil servants. These are the individuals who run government and carry out the public sector choices and policies on a day-to-day basis. Bureaucrats are not elected, which means they do not directly serve a group of constituents. The public choice view of bureaucrats is that they maximize power, prestige, and perks associated with operating that bureau. To accomplish this goal, bureaus maximize their budgets.

Public choice theory provides a way to evaluate collective decision making that not only allows for positive analysis but also addresses some of the normative issues associated with policy making. The rest of the research paper provides an overview of the origins of public choice theory and the contributions it has made to the discipline of economics.

Origins of Public Choice

Public choice economics emerged from public finance, which is the analysis of government revenues and expenditures. According to James Buchanan (2003), it was evident by the end of World War II and the early 1950s that economists did not have a good understanding of public sector processes. Economists began to realize that the naive public interest view did not reconcile with the reality of politics. Buchanan made his first endeavor into this issue in 1949. Around that same time, two other scholars began to examine a similar question. Duncan Black (1948) began examining the decision-making process of majority voting in committee settings. Kenneth Arrow (1951) was examining whether choices of the individual could be aggregated to create an overall social ordering of preferences. Arrow concluded in what is now known as his impossibility theorem that it is not possible to aggregate preferences to develop a social welfare function. The only way the preferences of individuals could be consistent with those of society is if a dictatorship existed and the preferences of society were those of the dictator’s. Arrow’s theoretical contributions served to inspire public choice theorists, but his contributions formally developed into what is now known as social choice theory. Social choice theory is focused on the concern of social welfare and the public’s interest. It examines how collective decisions can be made to maximize the well-being of society. Further analysis of social choice theory is beyond the scope of this research paper (see Arrow, Sen, & Suzumura, 2002, for more on social choice).

Public choice theory was developed primarily on the work of Buchanan, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1986. Buchanan was inspired by Swedish economist Knut Wicksell, who can be considered a precursor to public choice theory. Wicksell’s focus on the role of institutions led Buchanan and Gordon Tullock (1962) to write The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. This seminal work is considered the origin of the public choice revolution (Gwartney & Wagner, 1988).

The public choice revolution that began in 1962 with The Calculus of Consent called into question not only how political decisions are made but also the role of government in the private sector. Prior to the development of public choice theory, many economists argued that there are instances when private markets will fail to allocate resources efficiently: externalities, public goods, and monopolies. The conventional view was that government intervention could improve the allocative efficiency through taxes, government production, or regulation of the market. Public sector officials were thought to make decisions based on the public’s interest and the improvement of the overall welfare of society. However, this view is at odds with the economic and political reality of public sector outcomes. While most economists do not favor policies such as price controls, tariffs, and regulatory barriers that impede competition, these types of policies are common public sector outcomes. More specifically, public choice economists started asking why, if government intervention is the means to correct market failure, does government enact policies that often increase economic inefficiency.

Public choice’s concept of all individuals acting in rational self-interest provided an answer to this question. It reminded us that government is not an entity that is seeking social welfare but is merely a set of rules under which decisions are made. While self-interest leads individuals to socially enhancing outcomes, via Adam Smith’s invisible hand, these same motivations under government institutions can actually create outcomes that are not beneficial to society. The conclusion that emerges from this field of economics is that if one is to acknowledge that market failure exists, one must recognize that government failure exists.

Voting in a Direct Democracy

The issue of voting and majority rule was at the forefront of the development of public choice theory, and it is still the subject of much of the literature written today. The numerous aspects of voting addressed by public choice scholars are too vast for this research paper; therefore, the focus is on the seminal work in this area.

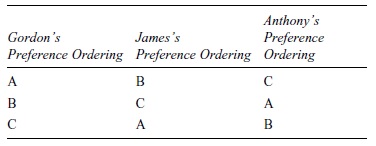

Majority Voting Cycles

Beginning with the work of Black (1948) and Arrow (1951), the idea emerged that if preferences are not single peaked when individuals vote for two candidates, referendums, or policies, majority voting can result in a cyclical voting pattern. This concept can be illustrated with Table 1. Three voters, Gordon, James, and Anthony, are represented across the top of the table, with each voter’s ranking of preferences represented by the order in the column. Thus, column 1 shows that Gordon ranks his preferences as A, B, and C. Similarly, columns 2 and 3 show the preferences of the other two voters. Based on the preferences of these three individuals, there is no decisive winner when these options are voted on in pairs. Option A paired with B will result in A winning. Option B will defeat Option C, and similarly, Option C will defeat Option A. The outcome will be determined by the number of elections that will occur and in what combination the options are paired. There is not a single option that wins the majority of votes. Two further concepts regarding voting, developed in light of voting cycles, are the median voter model and agenda manipulation.

Median Voter Model

The median voter model arises out of the need to assume single-peaked preferences. Single-peaked preferences exist when voters prefer one option above all other options. If single-peaked preferences exist, then cycling is no longer a concern. In addition, the option must be a single-dimensional issue, for example, measuring government expenditures from left (less) to right (more) on an x-axis. With these assumptions, a majority rule will lead to the median voter’s position always winning. The median voter model has several applications for evaluating voting decisions: committees, referenda, and representative democracies.

Table 1 Preference Analysis for Three Voters

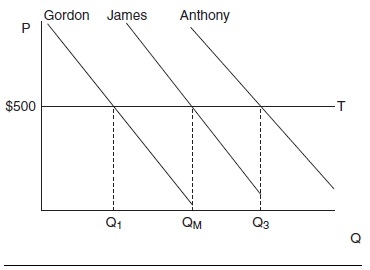

Figure 1 demonstrates the median voter model. Imagine that Figure 1 represents spending on education to be voted on by a committee. The price axis (P) represents the amount of education spending. Committee members Gordon, James, and Anthony all pay the same tax price (T) $500. The difference is the quantity they would like to receive for that tax price. The horizontal or quantity axis (Q) represents the amount of education each voter prefers. Gordon prefers quantity Q1, which is less than James, who is the median voter and desires QM, and Anthony prefers the largest quantity,Q3. Given the voters’ single-peaked preferences, the single dimension of the issue, and either a greater or lesser quantity of education at T, then in a majority vote,QM, the quantity preferred by James (the median voter), will always win. In a committee environment, Gordon would suggest Q1, his most preferred outcome; then James, the median voter, would counter with QM, his most preferred outcome. Gordon would vote for Q1, while James and Anthony would vote for QM, and QM would win by a vote of 2-to-1. If Anthony proposes Q3, then James would propose QM, and this quantity would again win by a vote of 2-to-1, Gordon and James having voted for QM and Anthony having voted for Q3. Any pairing with QM will result in QM winning because QM would be preferred by Gordon and Anthony over Q3 and Q1, respectively (Holcombe, 2005).

This proposition will also hold for a referendum, where the government would propose a quantity of education (still referring to Figure 1). If the referendum were to fail, another one would be proposed until the amount QM, which could win by a majority, was on the ballot.

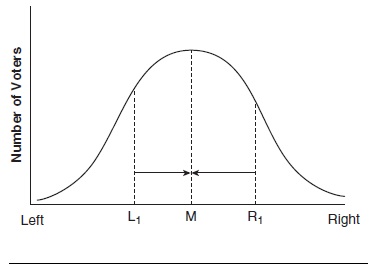

The median voter model, when applied to selecting a candidate, is a slightly different analysis. Voters decide on a candidate who will represent their preferred position on a multitude of issues—that is, a party platform. Figure 2 demonstrates the median voter model in the context of a representative democracy. Candidates for office can position themselves based on party platforms on the horizontal axis from left (liberal) to right (conservative). The vertical axis measures the number of voters that identify with that political position. One additional assumption is that the distribution of voters is normal across the population so that the most voters exist at the median (M).

The median voter model in this context was first presented by Harold Hotelling (1929). Hotelling argued that businesses and politicians, in a two-party system, would locate at the median to attract the most customers and voters. It was Anthony Downs (1957) who first suggested that political parties are strategic in their adopting of policies. According to Downs, “Parties formulate policies in order to win elections, rather than win elections in order to formulate policies” (p. 28). Politicians, as rationally self-interested actors, are concerned with winning elections and will therefore run on policies that will appeal to the decisive median voter. In Figure 2, candidate L1 and candidate R1 will both move toward M, where the greatest numbers of voters reside, in order to maximize their vote shares. Thus, candidates want to present policies that appear as centrist or “middle of the road” as possible. This will allow the candidate to attract all the votes to the left of his or her position for L1 (or right for his or her position for R1) plus M—and possibly voters to the right of M if he or she is closer to M than R1 (or left of M if he or she is closer to M than L1). One conclusion from this application is that extreme candidates to either the right or left cannot win elections dominated by a two-party system.

Figure 1 Median Voter Model for a Committee

Figure 2 Median Voter Model in a Representative Democracy

Agenda Manipulation

In the presence of voting cycles, the agenda setter has significant power over the final outcome. With a committee structure, in the presence of cycles, the rules that dictate how the agenda will be set matter in determining the end result. An agenda setter, a committee chair, for example, who desires to have his or her preference be the outcome, can structure the votes to achieve this end. Following the example from Table 1, suppose that committee members are all voting sincerely for their preferences. Suppose that Gordon is the agenda setter and prefers Option A to B and C. He would pair Option B with C, knowing that B would win, and he would then propose Option A versus Option B. Option A would defeat Option B, and at that point, the agenda setter could suspend all further voting, and the result would be Option A. Joseph Harrington (1990) argues that even when the agenda setter is selected at random, in the presence of voting cycles, that individual has the advantage of acquiring his or her desired outcome over the other members of the committee. Public choice scholars have noticed that despite the focus on voting cycles, there appears to be stability in congressional committee voting (Tullock, 1981). Committees rely on a particular set of rules that allows an agenda setter to avoid these cycles.

Logrolling

Economists argue that voluntary exchange is always mutually beneficial, presumably without imposing costs on others. When an opportunity exits for parties to gain from exchange, it is in an individual’s rational self-interest to engage in that trade. Political decision making is no exception. One reason that voting may appear stable in the context of cyclical voting is the ability of politicians to exchange votes. Casting a vote does not indicate any intensity of preference. The congressperson from Michigan’s vote counts the same as the congressperson from South Carolina’s vote. However, the intensity of the preference associated with a piece of legislation may be greater for one congressperson than for another. While the actual buying or selling of votes is illegal, this process has been occurring as an informal practice since the beginning of legislatures. Vote trading or logrolling can be described as a “you scratch my back; I will scratch yours” process. Logrolling helps to explain why redistributive polices that benefit only a small segment of the population can be passed, and can continue to be passed, with regularity.

Suppose a congressperson from Michigan would like to pass a tariff that would protect the domestic automobile industry. This tariff will benefit the citizens of Michigan who work for that industry while citizens across the country bear the cost of the tariff. Why would a congressperson from South Carolina support this legislation if his or her constituents would not directly benefit from this policy? If the congressperson from South Carolina would like to receive votes for an infrastructure project, such as a bridge, he or she may vote for the tariff in exchange for the Michigan congressperson’s vote. The citizens of Michigan and the other states are unlikely to directly benefit from the building of a bridge in South Carolina in the same way that most citizens will not benefit from the tariff. These types of redistributive policies that benefit a specific congressperson’s district or state are known as pork barrel legislation.

One can argue that logrolling, especially in the case of pork barrel legislation, is simply tyranny of the majority, because these types of policies benefit one group of citizens at the expense of another. Overall, although trade occurs, there is no increase in net benefit for society, but the congress people from Michigan and South Carolina and their constituents may be better off. In the public sector, these benefits come at the expense of others. One conclusion, then, is that majority voting where logrolling occurs will always increase government spending on redistributive policies (Tullock, 1959).

Public Choice Applied to Representative Democracy

Thus far, the focus has been on direct democracy, where citizens or committees directly vote for some policy, but what about voting for representatives? In the United States, most citizens do not directly vote to pass legislation, although that is possible in the cases of referendums. Rather, they vote for politicians, who will in turn represent them at some level of government.

Paradox of Voting

Unlike private markets, where an equilibrium outcome exhausts the gains from trade, the costs and benefits associated with voting provide a different outcome. Voting for a representative presents a scenario where the costs outweigh the benefits. Economists argue that individuals will not participate in activities that will not provide a net benefit. If voting does not provide a net benefit, no one should vote, and yet people do vote. This paradox of voting can be better understood by further examining the theory of the rational voter.

Rational Voter Hypothesis: Instrumental Voting

The rational voter hypothesis was first developed by Downs (1957) and then further developed by Tullock (1967a) and William Riker and Peter Ordeshook (1968). This topic has generated scores of articles by public choice scholars and continues to be a topic of interest (see Aldrich, 1993). Here, the simple economic application of cost-benefit analysis is demonstrated. Instrumental voting is simply the voter weighing the expected benefits and costs of voting. The expected benefit of a voter’s preferred candidate’s win must be greater than the costs associated with voting. For an individual to vote, conditions must be such that PB – C > 0. B is the expected benefit that a voter receives if his or her candidate wins the election. P is the probability that one’s vote is decisive in determining whether the desired candidate wins the election. In its simplest calculation, one can think of P as UN, where N is the total number of voters participating in the election. Thus, as N gets large, the probability of being the decisive vote for one’s candidate becomes infinitesimally small. Dennis Mueller (2003, pp. 304-305) provides a more detailed calculation of P. Thus, the probability of one’s being the decisive vote for one’s preferred candidate is PB.C is the cost of voting: the opportunity cost of one’s time to actually go the poll and the time one may spend learning about the candidates. Given that the probability of a voter being decisive is perceived as nearly zero (in large elections), even a small cost of voting should keep the rational voter away from the polls.

To complicate matters, if Down’s hypothesis regarding candidates’ behavior and the median voter is correct, then candidates will quickly move to the center to capture the median voter and win the election. However, if both candidates position themselves at the median, how does the voter perceive a difference between the two candidates? As the candidates move to the middle, the benefit, B, one sees for voting for candidate L1 over R1 (to use the notation from Figure 2) becomes smaller. Thus, PB may be very small even in cases where P is not infinitesimally small. According to this logic, no one should ever vote, and yet millions of people turn out to vote in elections, hence the paradox. In an attempt to rescue the rational voter hypothesis, Tullock (1967a) and Riker and Ordeshook (1968) included an additional component in the voter’s calculation. They suggested that the calculation is PB + D – C > 0, where D is a psychic benefit from voting. This psychic benefit can be perceived as a desire to vote or to fulfill one’s civic duty. Therefore, if a voter participates in an election, then D must be larger than C.

Rational Voter Hypothesis: Expressive Voting

A further development of the rational voter hypothesis is expressive voting. The expressive voting hypothesis picks up where the instrumental hypothesis leaves off. The term D, or the psychic benefit one receives from voting, now includes the utility that one receives from being able to express one’s preference. Geoffrey Brennan and Buchanan (1984) and Brennan and Loren Lomansky (1993) took a slightly different view of expressive voting, suggesting that voters are still rational in turning out to vote—but not because their votes are decisive. In fact, the hypothesis now assumes that voters understand that they will not cast a decisive vote but instead find value in being able to express their preferences for particular candidates, even if they know that their votes will not change the outcome. Expressive voting has been likened to cheering for one’s team at a sporting event. One knows that cheering louder will not change the outcome of the game, but the fan wants to express his or her support for the team.

Rent Seeking

Perhaps Tullock’s (1967b) greatest contribution to the field of public choice is the concept of rent seeking, a term coined by Anne Krueger (1974). In a market economy, economists argue that firms seek profits. These profits (total revenue – total economic cost) provide necessary signals to entrepreneurs regarding how to direct resources. Industries that are earning profits will see increases in resources, and those that are experiencing losses will see resources leave the industry. The profit and loss signals are necessary for the existence of a well-functioning market economy. In all market activities, a business can profit only if it is in fact providing a good or service that is valued by consumers.

Rent seeking is the process of businesses, industries, or special interest groups attempting to gain profit through the political process. Politicians can supply policy that provides an economic advantage to a particular group, in the form of granting them monopoly power or regulation that creates barriers to entry. The policy would benefit this group at the expense of the existing or potential competitors. These rents from the creating, increasing, or maintaining of a group’s monopoly power involve payoffs large enough that groups are willing to expend effort to acquire them. More important, the process of rent seeking, unlike profit seeking, results in costly and inefficient allocation of resources.

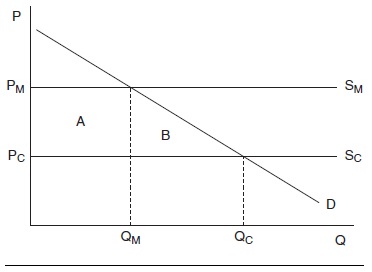

Suppose Figure 3 represents the market for cosmetologists (hair dressers). D is the demand for these services, and SC is the supply in a competitive market. A simplifying assumption is made that the marginal cost of serving one more customer is constant; hence, SC is horizontal. If this market operates competitively, the consumers will pay a price of PC and be supplied a quantity of QC. Now suppose that the existing members of the cosmetology industry hire lobbyists to persuade government officials to impose new regulations on the industry that create higher barriers to entry, giving existing members greater monopoly power. After the regulation is imposed, the costs of becoming a cosmetologist increase, causing the supply curve to shift from SC to SM. Consumers now pay the higher price of PM, and the cosmetologists will reduce the quantity to QM.

Figure 3 Rent Seeking in the Cosmetology Market

In a traditional monopoly analysis, the area labeled A would be known as the welfare transfer. The suppliers gain Area A at the expense of the consumers in this market. These are the rents that the cosmetology industry is seeking through the political process. Area B is the deadweight loss, the loss of consumer and producer surplus. However, Tullock (1967b) argued that both Areas B and A are deadweight losses. Area A is the rents that can be extracted by the group through the use of government power. In this example, the cosmetology industry is willing to pay up to the amount of A to receive these rents. Real resources must be used to acquire these rents. The industry would hire lobbyists, lawyers, and consultants to meet with government officials. It may engage in a media campaign to justify the new regulations. In addition, there are other groups, perhaps consumers or a competing interest group, that may spend resources in an attempt to prevent this regulation. These are costs above and beyond what may be gained by the cosmetology industry. In the end, Area B is a deadweight loss because real production is lost from QC to QM. Area A is a deadweight loss, or wasteful spending, because real resources are used to acquire these rents rather than to produce more real goods and services, and this creates regulation that promotes inefficiency in the market.

Rational Ignorance

If economists (and presumably government officials) realize that rent seeking is wasteful, why does it occur so often? To answer this question, we return to the supply and demand for public policy. Politicians can supply policy to different groups of voters: large, unorganized groups such as the working poor, the middle class, or college students; smaller, well-organized groups such as unions; industry-specific groups such as automobile manufacturers; or groups organized by occupation such as farmers. The unorganized groups are generally classifications of citizens that have only their individual votes. The organized or special interest groups provide contributions and often a large bloc of votes to a politician.

We know from our discussion of the rational voter hypothesis that the benefits from voting are extremely small, and the cost of voting may outweigh these benefits. More important, the costs of voting do not simply include the costs of voting on the day of the election but also the costs of knowing who or what is on the ballot. Being a well-informed voter is extremely costly. Voters have to research candidates’ records and policy positions, which are often not fully provided by the media or in the candidate’s literature. Citizens have to be aware of the goings-on within in their legislative body. The problem is that being a well-informed voter does not change the probability or benefit of voting. Well-intentioned and informed voters might participate only to see none of their proposals or candidates win. Thus, there is little benefit to being a well-informed voter. Therefore, the self-interested voter is rationally ignorant.

Voters focus on the few policies that matter to them and become aware of only whether the politician supports their view. It is rational for voters to remain ignorant of most issues and incur only the costs associated with the issues that are most important to them. A consumer shopping for a new car will not test-drive every make and model before purchasing the car. At some point, the additional information that can be gained from driving another car will be less than the cost associated with that test-drive. The same idea applies to voters: Beyond a certain point, trying to gather more information about a candidate will prove too costly for the benefit, and voters choose to be ignorant.

It is this rational ignorance of voters that allows wasteful rent-seeking policies to occur. Most citizens remain unaware of the regulations surrounding a particular industry and the motivations for imposing them. It is also important to realize that well-organized special interest groups have the incentive to be well informed. The benefits to the special interests are large, relative to the dispersed costs imposed on the taxpayers.

Legislatures, Bureaucracies, and Special Interest Groups

If politicians want to maximize votes to win elections, they can appeal to rationally ignorant voters in ways that convince the citizens to vote for them. For example, a politician campaigning on a college campus may speak on issues of affordable higher education. Rationally ignorant voters now know that this candidate will promote a policy that will benefit college students. These students may not seek any additional information on the candidate and may proceed to vote for him or her. Building on the concepts developed in this research paper, we can see that legislators will supply public policy to special interest groups in addition to broad groups of voters. Legislators using logrolling and relying on the rational ignorance of voters will allow special interest groups to rent seek in an effort to win or remain in office.

Special interest groups are typically organized based on industry, occupation, or a political cause. Mancur Olson (1965) argued that when these groups form to promote the interests of the group, they take on the characteristics of public goods, which means they suffer from the free-rider problem. Therefore, he argued that these groups will be more effective when they are relatively small, and if they are large, they require what Olson referred to as selective incentives to minimize the free-rider problem. An example of a selective incentive is a union’s requiring that members have dues deducted from their wages so that members cannot receive the benefits of the union without incurring the costs. Public choice economists have made two arguments regarding why special interest groups contribute to elections: (1) in an effort to (re)elect politicians and (2) to influence the way a politician votes on a public policy relevant to the special interest group.

Political action committees (PACs) are the legal or formal method by which special interest groups make contributions to legislators. The empirical literature on the influence of PACs on elections and legislation is numerous. James Kau and Paul Rubin (1982, 1993), Michael Munger (1989), Kevin Grier and Munger (1991), and Thomas Stratmann (1991, 1992, 1995, 1996, 1998) find evidence that PACs give to a legislator, with the hope of influencing the legislator’s votes and not merely to improve his or her chance to win office. For a brief review of this literature, see Mueller (2003). Calcagno and Jackson (1998, 2008) argue that PAC spending increases roll call voting, the voting on legislation, for members of the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives. Thus, public choice economists argue that special interest groups have more influence on political decision making for three basic reasons: (1) Politicians want to win elections, and special interest groups (PACs) can offer money and votes to improve the odds of winning; (2) voters are rationally ignorant of the policies that special interest groups are lobbying for or against; and (3) these policies offer concentrated benefits to special interest groups and widespread costs on individual voters.

Bureaucrats run the government on a day-to-day basis and include everyone from the clerk at the Department of Motor Vehicles to the head of the Food and Drug Administration. These individuals are primarily appointed and are not subject to the same accountability as politicians. These individuals cannot be voted out of office and many remain in these positions long after the politicians that appointed them have left office. William Niskanen (1971) was one of the first economists to examine bureaucracies from a public choice perspective. If bureaucrats, like everyone else, are rationally self-interested, what is it that they are maximizing? Niskanen argued that bureaucrats are budget maximizers. Larger budgets signal greater political power, prestige, and job security. Bureaucracies are difficult to monitor. This allows the bureaucrat to extract these nonpecuniary benefits. The model of bureaucracy is based on the monopoly model. The bureau is the only one producing a particular good or service for the public. Bureaucracies present to congress and the citizens an all-or-nothing demand curve. That means they can either produce the goods or services for a specific budget or not at all. This perception is in part due to the difficulty of monitoring bureaus. Beyond that, the output of bureaucracies is often difficult to measure, making it easier to present to the public a level of output that requires a specific budget.

Unlike the private sector, where managers have the incentive to improve production and are rewarded for their efficiency by higher profits, bureaucrats do not receive any such reward. Thus, the incentive to improve efficiency is not part of the bureaucracy’s institutional structure. Bureaucrats will seek larger and larger budgets under the guise of satisfying citizens. In addition, bureaus can appeal not only to satisfying the citizenry as a whole but also often provide a good or service that is specific to a special interest group. In an effort to expand the bureau’s patronage, bureaucrats make the special interest group aware of the goods or services they provide that benefit the group. Providing these goods or services encourages special interest groups to pursue rent-seeking behavior—that is, more benefits for the special interest group. Providing more goods or services allows bureaus to expand in size, scope, and budget.

Government as Leviathan

If politicians are maximizing votes, bureaucrats are maximizing budgets, special interest groups are dominating the political process, and voters are rationally ignorant, then the logical conclusion is the theory of government as Leviathan. Rather than a benevolent government, which seeks to aid the public’s interest, the theory of Leviathan suggests government is a monopolist with the sole interest of maximizing revenue. Government officials use cooperation— or whatever means they are constitutionally permitted— to generate as much revenue as citizens will allow. This view of government is at odds with traditional public finance, which suggests that there are optimal levels at which to tax citizens and that government officials are constrained by their accountability to citizens. If citizens (voters) are uninformed, government officials with the power to tax, spend, and create money are uncontrolled. Even with constitutional limits, rationally ignorant voters will not understand the amounts they are being taxed, the size of deficits and debt, and the impact of expanding money supplies. When government exceeds its constitutional limits, citizens may realize that they must monitor government more closely. However, these attempts to constrain government are often short lived. Voters attempted to constrain government with tax revolts in the 1970s and with the Contract with America (Mueller, 2003) in the early 1990s. Brennan and Buchanan (1980) provide a complete analysis of the theory of government as Leviathan.

Political Business Cycle

Although public choice is primarily a microeconomic field, it examines the macroeconomy through the prism of business cycles. Business cycle theories can be broadly categorized by their causes: (a) large declines in aggregate demand, (b) expansionary monetary policy, and (c) technological shocks to the economy. While business cycle theories may suggest that government policy may play a role in the creation of the business cycle, public choice scholars take this view one step further. Business cycles are the result of government policy, primarily through monetary expansion, and these cycles coincide with election cycles. Political business cycle economists argue that politicians will attempt to improve economic conditions prior to elections so as to win reelection. Focusing on a simple trade-off between unemployment and inflation, politicians will pursue policies that will reduce unemployment and generate positive economic conditions. Monetary expansion and fiscal policy are used to reduce unemployment. Only after the election does the inflationary effect of the policy emerge, and the boom becomes a bust. At this point, the politicians start the cycle again. This opportunistic political business cycle in part relies on the rationally ignorant voter, but one wonders if voters are fooled over and over again by such policies. An alternative explanation is that voters are selecting politicians that they believe will benefit them. If unemployment is a concern for a voter, he or she may vote for a politician who reduces unemployment because it will specifically benefit the voter.

According to Jac Heckelman (2001), the first term of the Nixon administration provides anecdotal evidence of a political business cycle, and Heckelman suggested that it was Nixon’s administration that inspired early theoretical models:

Keller and May (1984) present a case study of the policy cycle driven by Nixon from 1969-1972, summarizing his use of contractionary monetary and fiscal policy in the first two years, followed by wage and price controls in mid-1971, and finally rapid fiscal expansion and high growth in late 1971 and 1972. (p. 1)

Similarly, Jim Couch and William Shughart (1998) find evidence that New Deal spending was higher in swing states than in states with greater economic need, suggesting that the spending was motivated by Roosevelt’s desire to be reelected. The empirical evidence of an opportunistic political business cycle has mixed results in the economics literature. In a recent study, Grier (2008) found strong support for the political business cycle. He found evidence that the real gross national product (GDP) rose and fell between the years 1961 and 2004, in conjunction with presidential election cycles.

Normative Public Choice

The Importance of Institutions

Like most economics, public choice is primarily positive economic analysis, which means it is used to explain what is or what will happen. However, because public choice examines the world of political decision making and these decisions affect factors such as economic growth, taxation, and individuals’ standards of living, it seems appropriate that it ventures into the realm of normative analysis, or the way things should or ought to work. The use of normative economics in public choice has focused on the role of institutions. It is not enough to understand why voters may chose a particular candidate under majority rule, but one must ask whether majority rule is the best institution to select elected officials. Gwartney and Wagner (1988) argued that if individual actors are going to generate outcomes that benefit society, then

success rests upon our ability to develop and institute sound rules and procedures rather than on our ability to elect “better” people to political office. Unless we get the rules right, the political process will continue to be characterized by special interest legislation, bureaucratic inefficiency, and the waste of rent-seeking. (p. 25)

Constitutional Economics

The normative aspect of public choice can be seen as the overlap with social choice theory. One major normative analysis that emerges from public choice theory is constitutional economics. As in social choice theory, the fundamental question addresses the best way for a society to be organized so as to maximize the welfare of its citizens. It is precisely this question that Buchanan and Tullock (1962) tried to answer in The Calculus of Consent. Constitutional economics can be thought of as both a positive and a normative analysis. In normative analysis, the argument for a constitution is similar to other social choice theories that address the concept of a social contract. Public choice theory starts with the first stage, a convention being called, to establish a constitution under uncertainty. The difference in these theories is the degree of uncertainty for the actors in this first stage of decision making. Buchanan and Tullock argue that in this first stage, collective decisions are really individual decisions in which each individual follows his or her own self-interest.

The constitutional convention requires unanimity to have a successful outcome. If everyone agrees to the constitution, everyone is agreeing to abide by the rules, even though some of those rules may ban or restrict their behaviors in the future. It is in this way that the uncertainty comes into play. The actors know that certain actions will reduce the utility of individuals in the future, but they do not know at that point whether they will be one of the individuals affected. A first-stage decision may be the voting rule used in future elections: simple majority rule, a two-thirds majority, or a three-fourths majority. By having unanimity in the first stage, everyone is agreeing to that rule without knowing whether they will be in the majority in the future. It is not until the second stage when individuals are actually voting on policies and candidates that they will know to what degree they will be affected by the first-stage decisions.

One contention in this theory is whether constitutions are contracts or conventions. The contract theory views constitutions as contracts agreed on and actually signed by the originators to signify their commitment. The convention view suggests that constitutions are devices by which social order and collective decisions are made. The convention view treats constitutions as self-enforcing, because all parties understand the convention or device by which decisions will be made and chose a convention in the first stage that maximizes social welfare. Thus, the second-stage decisions are easily agreed on, and no one has an incentive to violate the convention. The constitution-as-contract view requires an outside enforcement mechanism, such as a police force or a court system, to ensure that individuals do not violate the contract. Both views recognize that at the first stage, the rules need to be constructed to create an incentive structure consistent with individuals’ rational self-interest. Otherwise, in the second stage, individuals will generate outcomes that will not maximize social welfare. Constitutions possess characteristics of both contract and convention. Although the self-enforcing feature of conventions is desirable, one potential problem is that constitutions can evolve over time, and these decisions may be out of the citizens’ control. When a constitution is a contract, it is harder to change, but because the government enforces it, conflicts between the state and the citizen can arise.

Anarchy

It is precisely the idea of the state as a neutral party that has some public choice scholars asking whether constitutions are the right means of organizing society. As has been noted throughout this research paper, individuals, in the absence of sound institutions, will create outcomes that are inefficient. Instead of a constitutionally limited state, some economists argue that the logical conclusion of a public choice perspective is anarchy. Beginning in the 1970s, public choice economists began to examine the issue of anarchy. The initial results were pessimistic views that a state is still necessary to prevent individuals from plundering their neighbors. However, a younger generation of public choice economists has a more optimistic view (Stringham, 2005). The absence of government does not mean the absence of rules or laws but rather the form that they take. Private institutions, through voluntary exchange and contracts, will create a set of rules that individuals agree to abide by. This research is being revisited, and this question is being asked: Why not consider anarchy in the realm of possible choices?

Peter Boettke (2005) pointed out that public choice economics presents a puzzle. He argued that Buchanan suggested there are three potential functions for government: (1) protective, in which the state is protector of private property rights; (2) productive, in which the state improves inefficiency where warranted; and (3) redistributive. The first two features, many economists will argue, are desirable, but the third, the redistributive power of the state, is the one that exists but should be avoided. How do you create a state that will generate the first two and not the third? Boettke suggested that there is a fine line between opportunism and cooperation in individuals’ self-interested behavior. Does this require the state’s intervention, or can markets solve this puzzle? This issue provides an interesting area for future research in public choice.

Conclusion and the Future of Public Choice

It has been said the framers of the U.S. Constitution were the original public choice economists. Somewhere between the eighteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, this view of politics and institutions changed. Beginning in the 1940s and taking hold in the 1960s, public choice economics emerged to return us to this original vision. Using economic tools to examine political choices provided new insights into the field of public finance. The dichotomy of private decision making as self-interested and public decision making as altruistic was confronted with a single vision of economic humanity. Individuals, whether they are buying a car or deciding for which congressperson to vote, are now seen as behaving rationally self-interested.

Over the last half-century, the field of public choice has examined every aspect of political decision making from voting to politicians’ behavior and from campaign financing to the running of bureaucracies. The field of public choice has questioned whether political behavior drives our macroeconomy, debated the proper origins of the state, and asked whether the state can be contained and whether the state should even exist. Public choice economics has been integrated into the field of public finance and neoclassical economics to such an extent that not treating both private and public actors as rationally self-interested may be viewed as an incomplete analysis, perhaps even naive.

Public choice has tackled many of these issues, empirically finding strong evidence of rationally ignorant voters, rent seeking, vote-maximizing politicians, and the existence of an opportunistic political business cycle. It has ventured in the normative arena, asking what type of institutional arrangements will generate the greatest prosperity and maximize social welfare.

What has emerged from this field is an understanding that if market failure exists, so does government failure. Public choice economics presents a means by which market-based outcomes can be compared to public-sector outcomes and economists can decide which institutional arrangement, even if flawed, will likely lead to greater economic efficiency (Gwartney & Wagner, 1988).

Public choice theory continues to examine these issues, both empirically and from a normative perspective. Public choice theory continues to make contributions to the field of economics, analyzing every type of collective decision. With the government taking a larger and larger role in the economy, public choice will continue to prove a useful field of analysis.

Bibliography:

- Aldrich, J. H. (1993). Rational choice and turnout. American Journal of Political Science, 37, 246-278.

- Arrow, K. J. (1951). Social choice and individual values. New York: John Wiley.

- Arrow, K. J., Sen, A. K., & Suzumura, K. (Eds.). (2002). Handbook of social choice and welfare (Vol. 1). New York: Elsevier North-Holland.

- Black, D. (1948). On the rationale of group decision-making. Journal of Political Economy, 56, 23-34.

- Boettke, P. J. (2005). Anarchism as a progressive research program in political economy. In E. Stringham (Ed.), Anarchy, state, and public choice (pp. 206-219). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. M. (1980). The power to tax: Analytical foundations of a fiscal constitution. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. M. (1984). Voter choice: Evaluating political alternatives. American Behavioral Scientist, 28, 185-201.

- Brennan, G., & Lomansky, L. (1993). Democracy and decision. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Buchanan, J. M. (1949). The pure theory of government finance: A suggested approach. Journal of Political Economy, 57, 496-506.

- Buchanan, J. M. (1954). Individual choice in voting and the market. Journal of Political Economy, 62, 334-343.

- Buchanan, J. M. (2003). Public choice: The origins and development of a research program. Fairfax, VA: George Mason University, Center for Study of Public Choice.

- Buchanan, J. M., & Musgrave, R. A. (1999). Public finance and public choice: Two contrasting views of the state. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Calcagno, P. T., & Jackson, J. D. (1998). Political action committee spending and senate roll call voting. Public Choice, 97, 569-585.

- Calcagno, P. T., & Jackson, J. D. (2008). Political action committee spending and roll call voting in the U.S. House of Representatives: An empirical extension. Economics Bulletin, 4, 1-11.

- Couch, J. F., & Shughart, W. F. (1998). The political economy of the New Deal. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

- Grier, K. B. (2008). Presidential election and real GDP growth, 1961-2004. Public Choice, 135, 337-352.

- Grier, K. B., & Munger, M. C. (1991). Committee assignments, constituent preferences, and campaign contributions. Economic Inquiry, 29, 24-43.

- Gwartney, J., & Wagner, R. E. (1988). The public choice revolution. Intercollegiate Review, 23, 17-26.

- Harrington, J. E. (1990). The power of the proposal maker in a model of endogenous agenda formation. Public Choice, 64, 1-20.

- Heckelman, J. (2001). Historical political business cycles in the United States. In R. Whaples (Ed.), EH.Net encyclopedia. Available at http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/heckelman .political.business.cycles

- Holcombe, R. (2005). Public sector economics: The role of government in the American economy. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hotelling, H. (1929). Stability in competition. Economic Journal, 39, 41-57.

- Kau, J. B., & Rubin, P. H. (1982). Congressmen, constituents, and contributors. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Kau, J. B., & Rubin, P. H. (1993). Ideology, voting and shirking. Public Choice, 76, 151-172.

- Keller, R. R., & May, A. M. (1984). The presidential political business cycle of 1972. Journal of Economic History, 44,265-271.

- Krueger, A. O. (1974). The political economy of the rent-seeking society. American Economic Review, 64, 291-303.

- Mueller, D. C. (2003). Public choice 3. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Munger, M. C. (1989). A simple test to the thesis that committee jurisdictions shape corporate PAC contributions. Public Choice, 62, 181-186.

- Niskanen, W. A. (1971). Bureaucracy and representative government. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

- Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Riker, W. H., & Ordeshook, P. (1968). A theory of the calculus of voting. American Political Science Review, 62, 25-42.

- Stratmann, T. (1991). What do campaign contributions buy? Causal effects of money and votes. Southern Economic Journal, 57, 606-620.

- Stratmann, T. (1992). Are contributors rational? Untangling strategies of political action committees. Journal of Political Economy, 100, 647-664.

- Stratmann, T. (1995). Campaign contributions and congressional voting: Does the timing of contributions matter? Review of Economics and Statistics, 77, 127-136.

- Stratmann, T. (1996). How reelection constituencies matter: Evidence from political action contributions and congressional voting. Journal of Law and Economics, 39, 603-635.

- Stratmann, T. (1998). The market for congressional votes: Is timing of contributions everything? Journal of Law and Economics, 41, 85-113.

- Stringham, E. (Ed.). (2005). Anarchy, state, and public choice. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Tollison, R. D. (1982). Rent seeking: A survey. Kyklos, 35, 575-602.

- Tullock, G. (1959). Some problems of majority voting. Journal of Political Economy, 67, 571-579.

- Tullock, G. (1967a). Toward a mathematics of politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Tullock, G. (1967b). The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. Western Economic Journal, 9, 224-232.

- Tullock, G. (1981). Why so much stability. Public Choice, 37,189-202.