Sample Cross-Cultural Research Methods Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Cross-cultural studies involve persons from different countries and/or ethnic groups; a defining characteristic is their comparative nature. Most studies employ quantitative methods of data collection and analysis. Studies of cultural topics that are noncomparative and apply a qualitative methodology can be found in sociology (‘cultural studies,’ e.g., Alasuutari 1995), cultural psychology (Greenfield 1997), and cultural anthropology (Naroll and Cohen 1970).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The range of instruments used in comparative studies is very broad, ranging from highly standardized psychological tests, to observation schedules, and free interviews. In many studies existing Western instruments (mental tests, survey questionnaires, personality inventories) are administered in a new cultural context, either or not adapted to enhance their cultural appropriateness.

If two persons from different cultural groups show different scores on a reliable and valid measure of subjective well-being, these score differences may refer to individual differences in subjective well-being. However, the score differences may also arise from differential social desirability or some other response style, inappropriate translation, or inadequacy of the item to measure well-being in both groups. The example illustrates a central problem in cross-cultural research: observed score differences are often susceptible to multiple explanations (Campbell and Stanley 1966, Cook and Campbell 1979, Poortinga and Malpass 1986). When the same instrument has been administered to persons from different ethnic groups, it cannot be taken for granted that the same scores obtained in different cultural groups have the same psychological meaning.

The ambiguity of interpretation is a consequence of the methodological nature of culture as an independent variable. In laboratory studies researchers randomly assign subjects to experimental treatments. The random assignment leads to a firm control of ambient variables; ideally an experimental and control group are matched on all outcome-relevant characteristics (e.g., personality characteristics and socioeconomic status), except for the treatment variable studied. However, like gender and other intrinsic subject characteristics, culture is not an experimental treatment that can be manipulated. Groups with a different cultural background tend to differ on a variety of outcome-relevant characteristics. These differences may constitute rival explanations of observed cross-cultural differences. Without precautions to rule out these rival explanations, observed cross-cultural differences are open to multiple interpretations. Findings in cross-cultural research are more convincing when rival explanations have been more adequately dealt with.

Bias is the generic name of an important family of rival explanations. It refers to the common problem in the assessment of nonequivalent groups that scores obtained in different cultural groups are not an adequate reflection of the groups’ standing on the construct underlying the instrument. If scores are biased, their psychological meaning is group dependent and group differences in assessment outcome are to be accounted for, at least to some extent, by auxiliary psychological constructs or measurement artifacts. A closely related concept is equivalence which refers to the absence of bias and hence, to similarity of meaning across groups. The two concepts have somewhat different historical roots and areas of application. Whereas bias usually refers to nuisance factors, equivalence has become the generic term for metrical implications of bias.

Bias and equivalence are not inherent properties of an instrument but arise in a group comparison with a particular instrument. Score comparisons of groups that differ in more test-relevant aspects will show a higher susceptibility to bias.

1. Sources Of Bias

There are three bias sources in cross-cultural research. The first is called construct bias; it occurs when the construct measured is not identical across groups. Ho’s (1996) work on filial piety (psychological characteristics associated with being a good son or daughter) provides a good example. The Western conceptualization is narrower than the Chinese, according to which children are supposed to assume the role of caretaker of their parents when these grow old and become needy. Construct bias precludes the cross-cultural measurement of a construct with the same measure. An inventory of filial piety based on the Chinese conceptualization will cover aspects unrelated to the concept among Western subjects, while a Western-based inventory will leave an important Chinese aspect uncovered.

An important source of bias, called method bias, can result from sample incomparability, instrument characteristics), tester and interviewer effects, and the method (mode) of administration. Examples are differential stimulus familiarity in mental testing and differential social desirability in personality and survey research. Some sources of method bias can be dealt with by careful preparation of the assessment instrument and its instruction manual (e.g., proper test instruction with a clear specification of what is asked from participants, standardization of administration, and adequate training of testers and interviewers). Yet, it may be impossible to eliminate all outcome-relevant sample characteristics, in particular when the cultural distance of the countries involved is large. There are indications that a country’s Gross National Product (per capita) is positively related to its mean score on mental tests and negatively to its mean score on social desirability. Particularly in comparisons of culturally highly dissimilar groups it may be hard or even impossible to eliminate the impact of sources of method bias such as sources familiarity and social desirability.

Finally, bias can be due to anomalies at item level (e.g., poor translations); this is called item bias or differential item functioning. According to a definition that is used widely in psychology, an item is biased if persons with the same standing on the underlying construct (e.g., they are equally intelligent) but coming from different cultural groups, do not have the same average score on the item. The score on the construct usually is derived from the total test score. If a geography test administered to pupils in Poland and Japan, contains the item ‘What is the capital of Poland?’ Polish pupils can be expected to show higher scores on the item than Japanese students, even when pupils with the same total test score would be compared. The item is biased as it favors one cultural group across all test score levels. Of all bias types, item bias has been the most extensively studied; various psychometric techniques are available to identify item bias (e.g., Camilli and Shepard 1994; Holland and Wainer 1993).

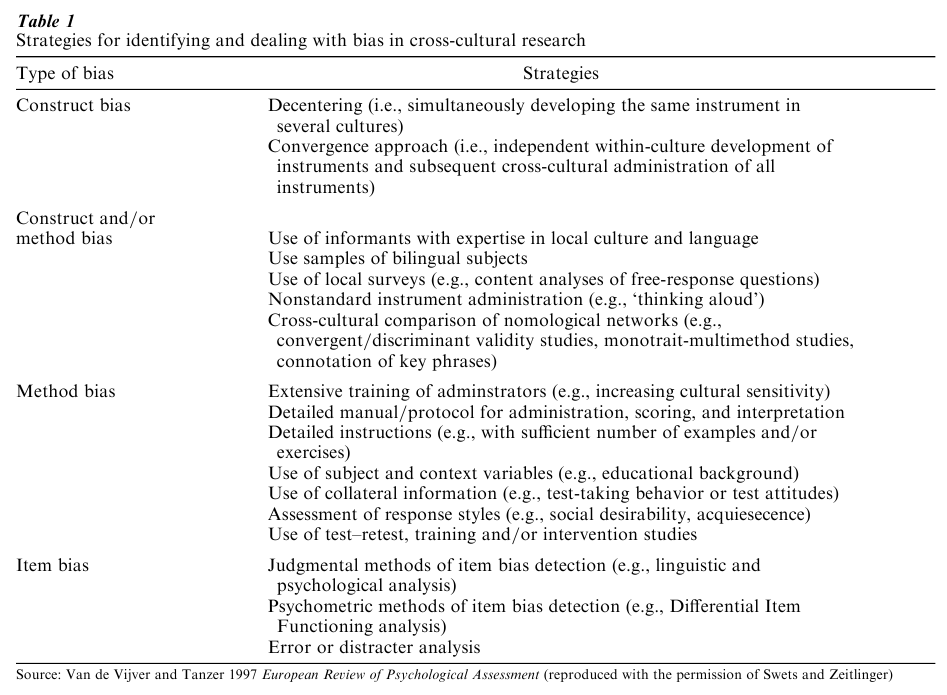

An overview of common ways of addressing bias is given in Table 1.

2. Types Of Equivalence

Elaborating on categorizations in the literature, four different types of equivalence are proposed here (cf. Van de Vijver and Leung 1997). The first type is labeled construct inequivalence. It amounts to com-paring apples and/oranges (e.g., the comparison of Chinese and Western filial piety, discussed above). Comparisons lack an attribute for comparison, also called tertium comparationis (the third term in the comparison). The second is called structural (or functional) equivalence. An instrument administered in different cultural groups shows structural equivalence if it measures the same construct in both groups (e.g., Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices test has been found to measure intelligence in various cultural groups). Exploratory factor analyses followed by target rotations or confirmatory factor analysis of correlation matrices (structural equation modeling) may be applied to examine structural equivalence. Structural equivalence does not presuppose identity of measures across groups. The measures may use different stimuli across groups. If different operationalizations have been chosen, structural equivalence can be examined by comparing nomological networks across groups.

The third type of equivalence is called measurement unit equivalence. Instruments show this type of equivalence if their measurement scales have the same units of measurement and a different origin (such as the Celsius and Kelvin scales in temperature measurement). This type of equivalence assumes interval- or ratio-level scores (with the same measurement units in each culture). It applies when a bias factor with a fairly uniform influence on the items of an instrument affects test scores of different cultural groups in a differential way. Social desirability and stimulus familiarity may exert this influence. Observed group differences in scores are then a mixture of valid cross-cultural differences and measurement artifacts. When the relative contribution of both sources cannot be estimated, the interpretation of group comparisons of mean scores remains ambiguous. Multigroup comparisons of confirmatory factor analytic models have been utilized to examine measurement unit equivalence. This technique, based on comparisons of covariance matrices, can identify bias sources that affect the covariance of items or tests but it cannot differentiate between valid differences in mean scores and bias sources with a uniform influence on all parts of an instrument.

Only in the case of scalar (or full-score) equivalence can direct comparisons be made; it is the only type of equivalence that allows for the conclusion that average scores obtained in two cultures are different. This type of equivalence assumes the same interval or ratio scales across groups. Conclusions about which of the latter two types of equivalence applies are often difficult to draw and controversial. For example, racial differences in intelligence test scores have been interpreted as due to valid differences (scalar equivalence) and as reflecting measurement artifacts (measurement unit equivalence). Scalar equivalence assumes that the role of bias can be safely neglected. The demonstration of scalar equivalence draws on inductive argumentation. Therefore, it is easier to disprove than to prove scalar equivalence. This can be made plausible by measuring presumably relevant sources of bias (such as stimulus familiarity or social desirability) and showing that they cannot statistically explain observed cross-cultural differences in a multiple regression or covariance analysis.

The distinction between the latter two types of equivalence is immaterial when comparing experimental conditions or changes across cultures (e.g., developmental trajectories or training effects). Scales that show measurement unit equivalence, measure changes at the level of full score equivalence.

Structural, measurement unit, and scalar equivalence are hierarchically ordered. The third presupposes the second, which presupposes the first. Moreover, higher levels of equivalence are more difficult to establish. It is easier to demonstrate that an instrument measures the same construct in different cultural groups (structural equivalence) than to demonstrate numerical comparability across cultures (scalar equivalence). On the other hand, higher levels of equivalence allow for more detailed comparisons of scores across cultures. Whereas in the case of structural equivalence, only factor structures and nomological networks can be compared, scalar equivalence allows for more fine grained analyses of cross-cultural similarities and differences, such as comparisons of mean scores across cultures in t tests and analyses of (co)variance.

2.1 Linguistic Equivalence

The concept of linguistic equivalence is developed in multilingual studies. Versions of an instrument in different languages show linguistic equivalence if these have the same characteristics that are relevant for the measurement outcome such as meaning, connotations of words and sentences, comprehensibility, and read-ability. Linguistic equivalence can be jeopardized by various sources, such as incorrect translations, words that are hard or impossible to translate (e.g., the English ‘distress’ does not have an equivalent in many languages), idiomatic expressions and metaphors (e.g., ‘feeling blue’), and imprecise quantifiers (‘rather often’).

Because linguistic equivalence is not always guar-anteed by a literal translation, it has become increasingly popular to utilize adaptations. In an adaptation, parts are changed (instead of literally translated) with the aim to improve an instrument’s suitability for a target group.

Many studies employ a translation–back-translation procedure (Brislin 1986, Werner and Campbell 1970). This amounts to a translation, followed by an independent back-translation and a comparison of the original and back-translated version, possibly followed by some alterations of the translation. Such a procedure provides a powerful tool to enhance the correspondence of original and translated versions that is independent of the researcher’s knowledge of the target language. Yet, it also has some disadvantages. It puts a premium on literal reproduction; this may give rise to a stilted language use in the target version that lacks the readability and natural flow of the original. The problem may be compounded by translators’ awareness of their involvement in a translation–back-translation procedure.

A second problem involves translatability. The use of idiom (e.g., the English ‘feeling blue’) or references to cultural specifics (e.g., references to country-specific public holidays) or other features that cannot be represented adequately in the target language challenges translation–back-translations designs (and in-deed all procedures in which existing instruments are translated). During the 1990s there was a growing awareness that translations and adaptations require the combined expertise of social and behavioral scientists (with a competence in the construct studied) and experts in the target language(s) and culture(s). In this so-called committee approach in which the expertise of all relevant disciplines is combined, there is usually no formal accuracy check of the translation. Usage of the committee approach is popular in large international bodies in which texts are translated in many languages like the United Nations and the European Union.

When versions in all languages are developed simultaneously, a procedure called ‘decentering’ (Werner and Campbell 1970) can be used. No single instrument or cultural group is then taken as starting point; individuals from different cultures jointly develop an instrument, thereby reducing the risk of introducing unwanted references to a specific culture.

The judgmental evidence of the designs to enhance linguistic equivalence can be easily combined with statistical approaches to establish equivalence. Reports of multilingual studies often provide a combination of judgmental–linguistic and empirical- –statistical evidence to demonstrate the adequacy of an instrument and its translation. There is a tradeoff between the type of translation and the level of equivalence that can be obtained. When most or all questions of an instrument are adapted, structural equivalence is the highest level possible. When most or all items are literally translated, measurement unit and structural equivalence can be obtained. Recent statistical advancements in item response theory and structural equation modeling have made it possible to retain scalar equivalence, even when not all stimuli are literally translated (provided that all items measure the same underlying construct in each group).

3. Sampling Cultures And Subjects

Cross-cultural studies can apply three types of schemes to sample cultures. Three types of sampling can be envisaged. The first is probability (or random) sampling. Because of the large cost of a probability sample from all existing cultures, it often amounts to stratified (random) sampling of specific cultures (e.g., Western cultures). The second and most frequently observed type of culture sampling is convenience sampling. The choice of cultures is governed here by availability and cost efficiency: researchers decide to form a research network and all participants collect data in their own country. In the third type, called systematic sampling, the choice of cultures is more based on substantive considerations. A culture is deliberately chosen be-cause of some characteristic, such as in Segall et al.’s (1966) study in which cultures were chosen on the basis of features of the ecological environment such as openness of the vista.

In survey research there is a well-developed theory of subject sampling (Kish 1965). In the area of cross-cultural research three types of sampling procedures of individuals are relevant as they represent different ways of dealing with confounding characteristics. The first is probability sampling. It consists of a random drawing from a list of eligible units such as persons or households. Confounding variables are not controlled for. The second type is stratified sampling. A population is stratified (e.g., in levels of schooling or socioeconomic status) and within each stratum a random sample is drawn. The purpose of stratification is the control of confounding variables (e.g., matching on number of years of schooling). The procedure cannot be taken to adequately correct for confounding variables when there is little or no overlap of the cultures (e.g., comparisons of literates and illiterates). The third procedure combines random or stratified sampling with the measurement of control variables. The procedure enables a statistical control of ambient variables (e.g., using an analysis of covariance).

4. Individual-And Country-Level Studies

The 1990s saw a growing interest in studies combining individual- and country-level data. Two kinds of studies have been reported. In multilevel hierarchical models (Bryk and Raudenbush 1992), a regression model is used to explain individual variation (e.g., explaining pupils’ achievement scores on the basis of their intelligence) and class, district, or country variation (e.g., the explanation of the relationship between intelligence and achievement by means of school quality indicators). The second line of research involves the study of the same phenomena at different levels of aggregation (multilevel covariance structure analysis or multilevel factor analysis, Muthen 1994). From a conceptual point of view this line is more complicated, because it is well documented that (des)aggregatation can lead to methodological artefacts such as the ecological fallacy, the incorrect application of culture-level characteristics to individuals. In each country a proportion of women is pregnant, but obviously, this proportion does not apply to any individual woman. In addition, equivalence issues have to be dealt with (Leung 1989). Hofstede’s famous study of values is based on country characteristics; the four dimensions he reported (individualism, power distance, uncertainty reduction, and masculinity– femininity) are characteristics of countries and their applicability to individual behavior cannot be taken for granted and has to be established. Multilevel covariance structure and factor analysis are powerful tools to examine the equivalence of phenomena at different levels of aggregation, answering questions like the structural (in)equivalence of concepts like individualism–collectivism at individual and country level. For these and various other concepts the structural equivalence at different levels of aggregation is still unresolved.

Bibliography:

- Alasuutari P 1995 Researching Culture. Qualitative Method and Cultural Studies. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Brislin R W 1986 The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Lonner W J, Berry J W (eds.) Field Methods in Cross-cultural Research. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

- Bryk A S, Raudenbush S W 1992 Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

- Camilli G, Shepard L A 1994 Methods for Identifying Biased Test Items. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Campbell D T, Stanley J C 1966 Experimental and Quasi- experimental Designs for Research. R McNally, Chicago

- Cook T D, Campbell D T 1979 Quasi-experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings. R McNally, Chicago

- Greenfield P M 1997 Culture as process: Empirical methods for cultural psychology. In: Berry J W, Poortinga Y H, Pandey J (eds.) Handbook of Cross-cultural Psychology, 2nd edn. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, Vol. 1

- Hambleton R K 1994 Guidelines for adapting educational and psychological tests: A progress report. European Journal of Psychological Assessment (Bulletin of the International Test Commission) 10: 229–44

- Ho D Y F 1996 Filial piety and its psychological consequences. In: Bond M H (ed.) Handbook of Chinese Psychology. Oxford University Press, Hong Kong

- Hofstede G 1980 Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

- Holland P W, Wainer H (eds.) 1993 Differential Item Functioning. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

- Kish L 1965 Survey Sampling. J Wiley, New York

- Leung K 1989 Cross-cultural differences: Individual-level vs. culture-level analysis. International Journal of Psychology 24: 703–19

- Muthen B O 1994 Multilevel covariance structure analysis. Sociological Methods and Research. 22: 376–98

- Naroll R, Cohen R (eds.) 1970 A Handbook of Cultural Anthropology, 1st edn. American Museum of Natural History, Garden City, New York

- Poortinga Y H, Malpass R S 1986 Making inferences from cross-cultural data. In: Lonner W J, Berry J W (eds.) Field Methods in Cross-cultural Psychology. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

- Segall M H, Campbell D T, Herskovits M J 1966 The Influence of Culture on Visual Perception. Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, IN

- Van de Vijver F J R, Leung K 1997 Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-cultural Research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Van de Vijver F J R, Tanzer N K 1997 Bias and equivalence in cross-cultural assessment: An overview. European Review of Applied Psychology 47: 263–80

- Werner O, Campbell D T 1970 Translating, working through interpreters, and the problem of decentering. In: Naroll R, Cohen R (eds.) A Handbook of Cultural Anthropology, 1st edn. American Museum of Natural History, Garden City, New York