View sample Types of Social Change Research Paper. Browse other social sciences research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Two sets of assumptions must be made explicit to identify different types of social change. The actor’s attributes are needed to understand what they do and why. The social structure—options and payoffs— within which the actors choose and act are needed to explain what happens and why. The two sets of assumptions are needed to construct a logical narrative of systemic effects.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Changes can consist in either

(a) the actors changing: what they want, know, do, obtain, or are burdened with, i.e., actor change in cognition, attitudes, sentiments, attributes, actions; or

(b) the structure changing: i.e., change of states, their correlatives or distributional aspects. These face the actors as facts, options, or structured costs and benefits, such as property rights, vacancies, socially available marriage partners, health hazards, or language boundaries.

The structure may change the actors, their hearts and minds. The actors may change the structure, its positions and possibilities. And the actors may react to conditions they have brought forth—by an echo effect, so to speak, from an edifice of their own making.

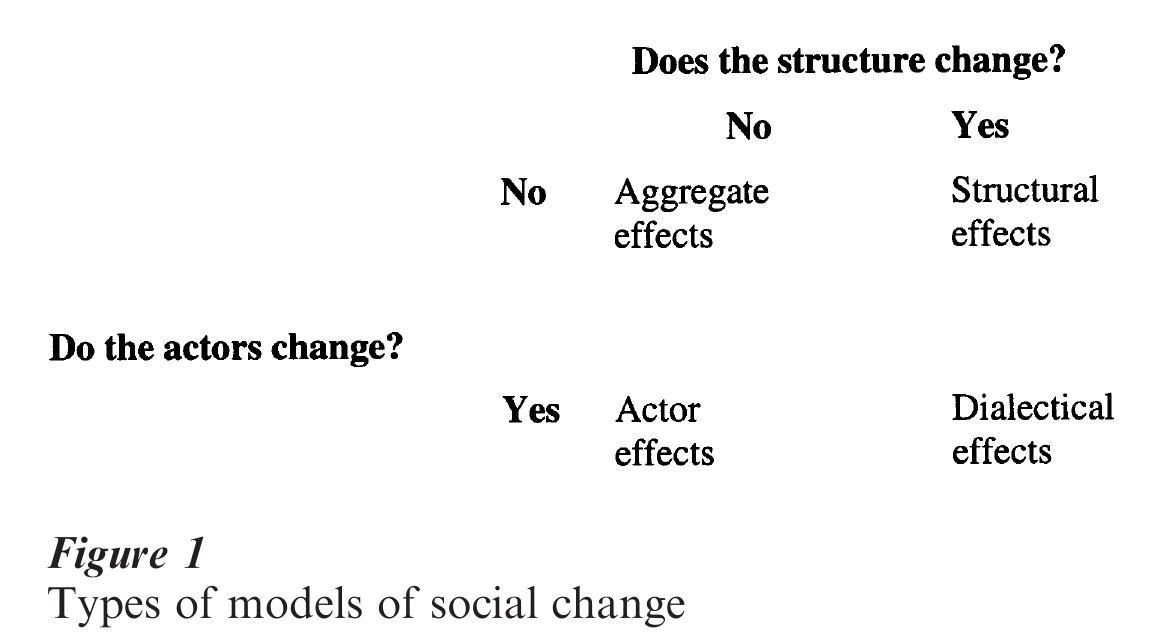

From answering two questions: (a) do the actors change, and (b) does the structure change, we may identify four kinds of models of social change, as shown in Fig. 1. Examples from classical texts below illustrate these types.

1. Models Of Aggregate Effects

An example of a model of ‘aggregate effects’ is found in microeconomic theory. Under ‘pure barter,’ each actor is assumed to prefer certain combinations of goods, to know who commands what goods, etc. Among the structural assumptions are that actors have rights to goods, that goods can be exchanged freely without transaction costs, etc. From such assumptions it follows that the actors will barter goods they like less for goods they want more. The driving force is the initial gap between what they have and what they want—between what they actually prefer and what they initially control. Hence, a new distribution of goods will arise among the actors from which nobody will want to move because none can get more satisfaction from another exchange. The actors themselves remain unchanged, as does the value of their goods. The model is one of change only in the sense than that the actors’ bundles of goods at the end are different from the outset. Hence economists call this genre ‘models of static equilibrium,’ though a process runs until this equilibrium is reached. Distributional characteristics may be modified—e.g., the degree of concentration of goods. But they have no further motivational effects in these models—the actors’ choices shape the final allotment of goods, but they do not react to it once equilibrium is reached. The distribution of final control is just an aggregate outcome, not input for further action. Economics has many variations on this theme. It is a separate, empirical question to what extent such a model agrees with a barter process in the real world.

There are even more stripped down models of aggregate effects. A stable population model assumes nothing about what the actors want or know—only that they have constant probabilities of offspring and death at specific ages. Initially the population pyramid may deviate from its final shape. Having arrived there, it will remain unchanged. The stable proportions in the different age sex categories are equilibrium states which represent the ‘latent structural propensities of the process characterized by the [parameters]’ (Ryder 1964, p. 456)—the values that proportions move toward when parameter values remain constant. For some, even important, phenomena, cut down actor models (no intentions or knowledge) are powerful. Simple assumptions can take you a long way in making a logical narrative.

2. Models Of Actor Effects

The second type of model is illustrated by ‘learning by doing.’ In Capital, Marx describes how a specialist (a ‘detail laborer’) acquires skills within manufacture production. A ‘collective laborer’ is the organized combination of such specialists. Manufacture ripens the virtuosity of the ‘detail laborer’ in performing his specialized function by repetition:

A labourer who all his life performs one and the same simple operation, converts his whole body into the automatic, specialized implement of that operation. Consequently, he takes less time doing it, than the artificer who performs a whole series of operations in succession. But the collective labourer, who constitutes the living mechanism of manufacture, is made up solely of such specialized detail labourers. Hence in comparison with the independent handicraft, more is produced in a given time, or the productive power of labour is increased. Moreover, when once this fractional work is established as the exclusive function of one person, the methods he employs become perfected. The workman’s continued repetition of the same simple act, and the concentration of his attention on it, teach him by experience how to attain the desired effect with the minimum of exertion. (Marx [1864] 1967, p. 339)

The first logical element of this argument is actor assumptions:

(a) Actors are purposive—i.e., they seek desired effects. Indeed, Marx was no strict determinist, but assumed purposive action explicitly:

A spider conducts operations that resemble those of a weaver, and a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality. And at the end of every labor-process, we get a result that already existed in the imagination of the labourer at its commencement. He not only effects a change of form in the material on which he works, but he also realizes a purpose of his own. (Marx [1864] 1967, p. 178)

(b) The actors are satisficing, i.e., they start pursuing their goals by procedures that may not be the best (which provides room for improvement).

(c) They recognize deviations from present satisfactory performance.

(d) They evaluate deviations as either positive or negative by a criterion such as the ‘principle of least effort’ (to attain the desired effect with the minimum of exertion).

(e) There are two sources of deviation from current routines. The actors may search for better solutions, i.e., purposively probing for improvements by ‘trial and error.’ Or actors make mistakes—a stochastic element producing random departures from current routines. Accidentally hitting better solutions could be called ‘spot and snatch.’ Hence the model has two sources of new alternatives—deliberate exploration and random variation—one sought ex ante, the other sighted ex post.

In short, behavior is result controlled: when the outcome of an action deviates from the intended result, actors may modify their conduct. Negative deviations in terms of an actor’s purposes will be avoided and result in a return to the standard routine. Positive deviations will be retained.

The second logical element is the structure assumptions of Marx’ selection model:

(a) The actors are set to repetitive tasks.

(b) There are alternative ways of carrying out the tasks.

(c) The choice of alternative has consequences for the actors, being rewarding or penalizing in terms of their goals. These consequences may be due to laws of nature (e.g., efforts required or difficulties encountered) or they can be socially organized (e.g., reducing costs or increasing payoffs).

Such are the assumptions of Marx’ argument. He constructed a selection model which at the individual level works like this: the probability of mistakes is cut with every attempt, while methods giving better results are retained. Initially satisfactory but unwieldy procedures are abandoned—more effective ones are kept when captured, e.g., by the principle of least effort. Hence the laborer becomes a special tool for the task at hand—more adept and adroit. The best form found solidifies into a routine. And the collective worker as the sum of detail laborers can reach a perfection beyond any single individual carrying out all operations alone. Manufacture begets handicraft industries that push the skills required for carrying out a specific task in the same direction. The progression toward a best response pattern hence leads to homogenization of actions.

In short, on the assumptions of purposive action and selection of beneficial deviations, Marx explains individual adaptation as well as uniforming selection—i.e., increased dexterity in repetitive tasks until the form best fitted to the task is found. Note that in this model what changes is not actors’ preferences but their skills—not what they want, but what they know. Their bias for less effort is stable.

There are other models where actors change without this being part of their intention or recognition— effects may occur behind their backs. For example, a contagious disease may immunize a group against further outbreaks even if neither the contagion nor its effects are understood. If insights are won, actors may change practice, as when humans started to infect themselves with cowpox as protection against small- pox.

3. Models Of Structural Effects

The brilliant Norwegian sociologist Eilert Sundt (1817–75) provides an example of structural change inspired by the logic of mutations and selection found in The Origin of Species. ‘Learning by doing’ can modify not just behavior, but also material forms. Sundt had a keen eye for the logic of both error-based ‘spot and snatch’ and the more deliberate ‘trial and error’ mentioned above. In this quote, both the stochastic component in generating variation and the purposive element in discovery and selection of slight beneficial deviations are exposed lucidly:

A boat constructor may be skilled, and yet he will never get two boats exactly alike, even if he exerts himself to this end. The deviations occurring may be called accidental. But even a very small deviation usually is noticeable during navigation, but it is not accidental that the sailors come to notice that the boat that has become improved or more convenient for their purpose, and that they should recommend it to be chosen for imitation … One may think that each of these boats is perfected in its way, since it has reached perfection through one-sided development in one particular direction. Each kind of improvement has progressed to the point where further development would entail defects that would more than offset the advantage … Hence I conceive of the process in the following way: when the idea of new and improved forms had first been aroused, then a long series of prudent experiments each involving extremely small changes, could lead to the happy result that from the boat constructor’s shed there emerged a boat whose like all would desire. (Sundt [1862] 1976)

In this case, then, the material structure of society is modified via learning by doing. Note also that Sundt argued that the recognition of accidental discoveries (‘spot and snatch’) itself leads to the discovery of the usefulness of experiments (‘trial and error’), i.e., to second order learning. Marx used a similar line of argument to explain the differentiation of tools adapted to different tasks, and second order learning when science is used to improve industrial means of production.

Before turning to the fourth type, dialectical change, the analyses of Marx and Sundt may highlight how the same basic mechanism can be used to explain constancy as well as change, i.e., the evolution of social habits, tools, and organizational forms toward an optimal equilibrium pattern. Or, put differently, how continual trial and error leads to optimal responses which are then crystallized as customs, standard operating procedures, or best practices. The skills required are pushed in the same direction and the progression toward a best response pattern leads to homogenization of actions, i.e., to uniforming selection. Likewise, adaptation for divergent purposes generates differentiation. The essence of ordinary work is repetition—i.e., variations on the same theme. But by chance variations and serendipity, skills can be acquired, tools developed, and workgroups rearranged. This is how Marx explains changes in organizations and in aggregates at the macro level.

The first organizational consequence is that craftspeople, the best performers, may become locked into lifetime careers. The second organizational consequence is that, on the basis of skill and mastery, industry may sprout into different occupations—a structural change arising from the social organization of individual skills. That is, a particular task selects a best response that becomes fixed as a routine, different tasks select different types of best responses: ‘On that groundwork, each separate branch of production acquires empirically the form that is technically suited to it, slowly perfects it, and as soon as a given degree of maturity has been reached, rapidly crystallizes that form’ (Marx [1864] 1967, p. 485). Marx uses his selection model to explain structural differentiation. The resulting structure may be no part of any individual’s or group’s intentions, though it is a result of their choices.

By the same logic Marx explains change in the social structure of society as the gradual adaptation of different groups of workers. What is the best relative size of groups of specialized workers in different functions? Marx argues that there is a constant tendency toward an equilibrium distribution, forced by competition and the technical interdependence of the various stages of production:

The result of the labour of one is the starting-point for the labour of the other. The one workman therefore gives occupation directly to the other. The labour-time necessary in each partial process, for attaining the desired effect, is learnt by experience; and the mechanism of Manufacture, as a whole, is based on the assumption that a given result will be obtained in a given time. It is only on this assumption that the various supplementary labour-processes can proceed uninterruptedly, simultaneously, and side by side. It is clear that this direct dependence of the operations, and therefore of the labourers, on each other, compels each one of them to spend on his work no more than the necessary time, and thus a continuity, uniformity, regularity, order, and even intensity or labour, of quite a different kind, is begotten than is to be found in an independent handicraft or even in simple cooperation. The rule, that the labour-time expended on a commodity should not exceed that which is socially necessary for its production, appears, in the production of commodities generally, to be established by the mere effect of competition; since, to express ourselves superficially, each single producer is obliged to sell his commodity at its market price. In Manufacture, on the contrary, the turning out of a given quantum of product in a given time is a technical law of the process of production itself. (Marx [1854] 1967, p. 345)

There are two types of selection pressures in this argument: structural dependence, or integration that compels each to spend on his or her work no more than the necessary time, and economic competition. In short, the argument is based not just on purposive actors but on their location in a particular social macrostructure (competition) resulting in modification of another part of the structure (occupational composition). This argument also uses a conception of bottlenecks—a condition or situation that retards a process and thwarts the purposes of actors involved. This mode of explanation is often used by social scientists, e.g., for the logic of the industrial revolution: the invention of the Spinning Jenny made weaving a bottleneck and hence led to improved shuttles and machine looms requiring greater power to drive them, favoring the use of the steam engine, etc.

Learning in this case consists in gradual adaptation of group sizes to obtain the most efficient production. That definite numbers of workers are subjected to definite functions Marx calls ‘the iron law of proportionality’ (Marx [1854] 1967, p. 355). From firms, Marx moves on to the societal level: adjusting different work groups within the manufacture generates a division of labor at the aggregate or macro level.

Third, the basic selection model is used to explain not only change—i.e., the succession of steps towards the best suited response—but also constancy, i.e., the locking in of a structurally best response. ‘History shows how the division of labour peculiar to manufacture, strictly so called, acquires the best adapted form at first by experience, as it were behind the backs of the actors, and then, like the guild handicrafts, strives to hold on to that form when once found, and here and there succeeds in keeping it for centuries’ (Marx [1854] 1967, p. 363).

The fourth point made by both Sundt and Marx is a conceptual one: learning may take place not just by doing, but also through a second form of learning, namely, imitation. That is, those who have found the knack can be emulated, and, as Sundt argued, tools improved by accidents are chosen for imitation. Marx wrote: ‘since there are always several generations of labourers living at one time, and working together at the manufacture of a given article, the technical skill, the tricks of the trade thus acquired, become established, and are accumulated and handed down’ (Marx [1854] 1967, p. 339). In other words: socially organized purposive actors may learn vicariously. They recognize and copy the improved solutions others find to their own problems.

Basically then, Marx and Sundt argued that a constant technology advances the development of an equilibrium pattern of behavior, corresponding to the best possible practice, which also congeals social forms at the macro level. This takes place through the selection of the most adept methods by individuals, which, when aggregated, moves a group or even a mass of people from one distribution to another. They used selection mechanisms to explain a wide range of phenomena: development of individual dexterity, the evolution of lifetime careers, the homogenization of practices and the differentiation of tools, the evolution of occupations—indeed, the drift of large aggregates as well as equilibrium patterns and constancy.

The fifth point is that they considered new technology as a driving force which may require readaptation of behavioral responses (cf. Arrow 1962). From the notion of change moving toward an equilibrium or constancy Marx introduces the notion of the constancy of change. This happens when the random nature of learning by doing yields to the systematic search for new knowledge by applied science:

The principle, carried out in the factory system, of analysing the process or production into its constituent phases, and of solving the problems thus proposed by the application of mechanics, of chemistry, and the whole range of the natural sciences, becomes the determining principle everywhere. Hence machinery squeezes itself into the manufacturing industries first for one detail process, then for another. Thus the solid crystal of their organisation, based on the old division of labor, becomes dissolved, and makes way for constant changes. (Marx [1854] 1967, p. 461)

Marx’ explicit logic, therefore, was not just one of learning by doing and second order learning by outand-out search and science. He went even further in analyzing how the introduction of new implements required new learning by the users of those implements, and indeed, led to a change in attitudes as well. In other words, learning made people change their own conditions—by adapting to those conditions people changed themselves by learning to learn. This is the double logic of dialectical models.

4. Models of Dialectical Effects

Dialectical models analyze structures which motivate actors, by accident or design, to bring forth structural changes which then change the actors’ own attributes. In shorthand, such models look like this:

Structure → Actoral → Change → Structural Change → Actoral Change

This is, of course, a very important category for social analysis—the more so the longer the time perspective. People have not shaped the society into which they are born—they are molded by a society before they can remake it. But humans can remake themselves indirectly by changing the structure or culture within which they act. A classical text, Max

Weber’s (1904–5) The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, can serve to illustrate such models. Weber first identified a specific tendency among Protestants to develop economic rationalism not observed to the same extent among Catholics (Hernes 1989). Weber’s paradoxical thesis is that the supposed conflict between otherworldliness or asceticism on the one hand, and participation in capitalistic acquisition on the other, is in fact an intimate relationship.

Weber’s model departs from what he calls traditionalism, populated by two types of actors: traditionalistic workers, and traditionalistic entrepreneurs. The key attribute of the former is that increasing their rewards does not lead to an increase in their output, but rather makes them decrease the amount of work they put in. People ‘by nature’ do not want to earn as much as possible: traditionalistic workers adjust their supply of labor to satisfy their traditional needs. This ‘immense stubborn resistance’ is the ‘leading trait of pre-capitalist labor.’ Likewise, traditional entrepreneurs adjust their efforts to maintain the traditional rate of profit, the traditional relations with labor, and the traditional circle of customers.

However, what these actors want is not hardwired—their character can be changed. Weber wants to explain this change from the tranquil state of traditionalism to the bustling dynamism of capitalism. The first part of his argument is about how the actors’ temperaments are changed: how a homo no us—or rather two—is brought forth. The second part of the argument is about how they trap themselves and everyone else in the new conditions or structure they create. The new entrepreneurs came to see moneymaking as an end in itself. The new workers came to see labor as an end in itself. The argument runs briefly as follows.

In the beginning there was logic. Conceptual activity worked on beliefs to turn doctrines of faith into maxims for behavior. At the outset traditionalists had faith in God. He was omniscient and omnipotent. By pure logic this led to predestination: an omniscient God had to know ahead of time who were among the chosen; an omnipotent God must have decided already and must know the outcome of his decisions. Humans could do nothing to bring about their salvation by their own actions. Fates were preordained by God. Those who had salvation could not lose it and those without it could not gain it. What is more, neither group could know who had it. So for every true believer one question must have forced all others into the background: ‘Am I one of the elect?’ At first there seemed to be no answer; however, all the faithful were to act as if they were among the chosen. Doubts were temptations of the Devil—a sign of failing faith, hence of imperfect grace. And the faithful should act in the world to serve God’s glory to the best of their abilities. Those unwilling to work therefore had the symptoms of lack of grace. Hence there were some signs.

But the logic of this argument resulted in a peculiar psychology of signs—a mental reversal of conditional probability notions. The original argument ran: if you are among the elect, you work in a calling. The psychological reversal became: if you work in a calling, you have a sign that you are among the elect. Moreover, this sign— working—could be affected. By choosing to work hard, you attain a sign that you are among the chosen:

In practice this means that God helps them who helps themselves. Thus the Calvinist, as it is sometimes put, himself creates his own salvation, or, as would be more correct, the conviction of it. But this creation cannot, as in Catholicism, consist in a gradual accumulation of individual good works to one’s credit, but rather in a systematic self-control which at every moment stands before the inexorable alternative, chosen or damned. (Weber 1930, p. 115)

This is the first part of Weber’s analysis of actor change: the moral construction of the new actors— new workers and new entrepreneurs working in a calling for the glory of God—driven to restless work by their fierce quest for peace of mind.

However, this actoral change is not a sufficient condition to explain the structural change, i.e., the establishment of a new economic system—capitalism. Hence the next part of Weber’s logical chain is the following. Working in a calling was not enough. For even if many were called, few were believed chosen. Identifying who they were—and if one was among them—could only be done by comparisons. ‘Success reveals the blessings of God’ (Weber 1930, p. 271, n. 58). But success can only be measured in relative terms: ‘But God requires social achievement of the Christian because He wills that social life shall be organized according to His commandments, in accordance with that purpose’ (Weber 1930, p. 108, emphasis in original). Each Christian had, so to speak, to prove that he or she was ‘holier than thou.’ Moreover, each of them had to assess their success relative to others, and moreover, they had to do it in terms of economic achievement. The sign of salvation is not what you did unto others—it was whether you outdid the others.

Here is the nexus between actor change and structural change. From this mode of thinking, the individualistic Protestants were, so to speak, connected behind their backs. Religious attainment became measured by private profit. The market united those that theology separated. From being religious isolates the Christians became rivals—assessed by the relative fortunes they amassed. But then, to hold their own, they forced each other to work harder. In effect they set up a new social structure for themselves by their thinking and by their actions. Their religious mindset produced the new social setup. By taking not a good day’s work, but the relati e fruits of labor in a calling, as a measure of success, they in effect caught themselves in a prisoner’s dilemma.

Since capital accumulated but not capital consumed was measured, the logic of asceticism ‘turned with all its force against one thing: the spontaneous enjoyment of life and all it had to offer’ (Weber 1930, p. 166). Hence assets could also serve as a relative measure of success. And this had the ‘psychological effect of freeing the acquisition of goods from the inhibitions of traditionalistic ethic’ (p. 174). The double-barreled effect of ascetic Protestantism, in short, was to join the compulsion to work with the obligation to reinvest its output.

But the prisoner’s dilemma that the Protestants established by their particular comparative, even compulsive, work ethic not only captured their creators. By their logic of relative success they also dragged everybody else into the vortex of the market—they changed the social structure in a decisive way because it also entrapped all others:

The Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so. For when asceticism was carried out of the monastic cells into everyday life, and began to dominate worldly morality, it did its part in building the tremendous cosmos of the modern economic order. This order is now bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production which today determine the lives of all individuals who are born into this mechanism, not only those who are directly concerned with economic acquisition, with irresistible force. (Weber 1930, p. 181)

The structure that the actors created turned on themselves with a compelling might—their internal convictions transformed into external forces, so to speak. Moreover, not only are people compelled to react to conditions of their own making. The new structure of the competitive market in turn creates yet new types of actors without the religious motivation from which it sprang:

The capitalistic economy of the present day is an immense cosmos into which the individual is born, and which presents itself to him, at least as an individual, as an unalterable order of things in which he must live. It forces the individual, in so far as he is involved in the system of market relationships, to conform to capitalistic rules of action. The manufacturer who in the long run acts counter to these norms, will just as inevitably be eliminated from the economic scene as the worker who cannot or will not adapt himself to them will be thrown into the street without a job. Thus the capitalism of today, which has come to dominate economic life, educates and selects the economic subjects which it needs through a process of economic survival of the fittest. (Weber 1930, p. 54 f.)

By measuring success in relative terms, the Puritans established a prisoner’s dilemma in which they not only ambushed themselves and ensnared non-Puritans, but in addition, once it had been socially established, in turn liberated capitalism from its connection to their special Weltanschauung. It no longer needed the support of any religious forces: ‘Whoever does not adapt his manner of life to the conditions of capitalistic success must go under. But these are phenomena of a time in which modern capitalism has become dominant and has become emancipated from its old supports’ (Weber 1930, p. 72).

Hence, having explained the generation of the capitalist system, Weber takes competition to be source of its own reproduction, i.e., for the constancy of the new system. The paradox is that the religious belief that set people free from restraints on acquisitive activity, in turn liberated the resulting economic system from its creators and their beliefs. Once the new system is in place, it selects and shapes the actors needed to maintain it. The Protestant entrepreneurs who established the new system thereby in turn called forth yet another homo no us—industrialists and managers and workaholics infused not with Protestantism, but with the spirit of capitalism.

The short version of Weber’s analysis is this: religious conversion led to economic comparison; and the importance of relative success as a religious sign led to competition. This was a systemic transformation that in turn led not only to accumulation and innovation, but also to selection and socialization of new actors. A system brought into being by actors who feared eternal damnation bred actors who maintained it from concern for their daily survival and without religious qualms.

Weber’s analysis provides a very good example of dialectical change in that it explains how a new type of actor, with different beliefs and knowledge, modifies its own environment out of existence and in turn creates the conditions for yet another type of actor that is different from themselves. As Garrett Hardin (1969, p. 284) has written of ecological succession: ‘It is not only true that environments select organisms; organisms make new selective environments’ (cf. Hernes 1976, p. 533).

5. Conclusion

The analysis of change is at the heart of social theory because it attempts to answer this question: How do humans cope with the effects of their own creativity? To carry out such analysis one needs simple, yet potent, tools. They are embedded in the classical works of social science. When they are identified, we can emulate the best practitioners in the field.

Bibliography:

- Arrow K 1962 The economic implications of learning by doing. Review of Economic Studies 9(June): 155–73

- Hardin G 1969 The cybernetics of competition: A biologist’s view of society. In: Shephard P, McKinley D (eds.) The Subversive Science: Essays Towards an Ecology of Man. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, pp. 275–95

- Hernes G 1976 Structural change in social processes. American Journal of Sociology 38(3): 513–46

- Hernes G 1989 The logic of ‘The Protestant Ethic.’ Rationality and Society 1: 123–62

- Marx K [1864] 1967 Capital. International Publishers, New York

- Ryder N 1964 Notes on the concept of a population. American Journal of Sociology 69(March): 447–63

- Sundt E [1862] 1976 Om havet. In: Samlede verker. Gyldendal, Oslo, Vol. 7

- Weber M [1904–5] 1930 The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Talcott Parsons, Allen & Unwin, London