View sample Psychosocial Aspects of Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research Paper. Browse other social sciences research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) including HIV place an enormous burden on the public’s health. In 1995, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that, worldwide, there were 333 million new cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and trichomoniasis in 15to 49-year-olds. In 1999, WHO estimated that there were 5.6 million new HIV infections worldwide, and that 33.6 million people were living with AIDS. Although it is not who you are, but what you do that determines whether you will expose yourself or others to STDs including HIV, STDs disproportionately affect various demographic groupings. For example, STDs are more prevalent in urban settings, in unmarried individuals, and in young adults. They are also more prevalent among the socioeconomically disadvantaged and various ethnic groups. For example, in 1996 in the United States, the incidence of reported gonorrhea per 100,000 was 826 among black non-Hispanics, 106 among Native Americans, 69 among Hispanics, 26 among white non-Hispanics, and 18.6 among Asian/Pacific Islanders (Aral and Holmes 1999).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Demographic differences in STD rates are most likely explained by differences in sexual behaviors or disease prevalence. Thus, demographic variables are often referred to as risk markers or risk indicators. In contrast, sexual and healthcare behaviors that directly influence the probability of acquiring or transmitting STDs represent true risk factors. From a psychosocial perspective, it is these behavioral risk factors (and not risk markers) that are critical for an understanding of disease transmission.

1. Transmission Dynamics

To understand how behavior contributes to the spread of an STD, consider May and Anderson’s (1987) model of transmission dynamics: Ro = βcD, where, Ro = Reproductive Rate of Infection. When Ro is greater than 1, the epidemic is growing; when Ro is less than 1, the epidemic is dying out; and when Ro =1, the epidemic is in a state of equilibrium, β = measure of infectivity or tranmissability, c = measure of interaction rates between susceptibles and infected individuals, and D = measure of duration of infectiousness

Each of the parameters on the right hand side of the equation can be influenced by behavior. For example, the transmission rate (β) can be lowered by increasing consistent and correct condom use or by delaying the onset of sexual activity. Transmissibility can also be reduced by vaccines, but people must utilize these vaccines and before that, it is necessary for people to have participated in vaccine trials. Decreasing the rate of new partner acquisition will reduce the sexual interaction rate c and, at least for bacterial STDs, duration of infectiousness D can be reduced through the detection of asymptomatic or through early treatment of symptomatic STDs. Thus, increasing care seeking behavior and/or increasing the likelihood that one will participate in screening programs can affect the reproductive rate. Given that STDs are important cofactors in the transmission of HIV, early detection and treatment of STDs will also influence HIV transmissibility (β). Finally, D can also be influenced by patient compliance with medical treatment, as well as compliance with partner notification.

Clearly, there are a number of different behaviors that, if changed or reinforced, could have an impact on the reproductive rate Ro of HIV and other STDs. A critical question is whether it is necessary to consider each of these behaviors as a unique entity, or whether there are some more general principals that can guide our understanding of any behavior. Fortunately, even though every behavior is unique, there are only a limited number of variables that need to be considered in attempting to predict, understand, or change any given behavior.

2. Psychosocial Determinants Of Intention And Behavior

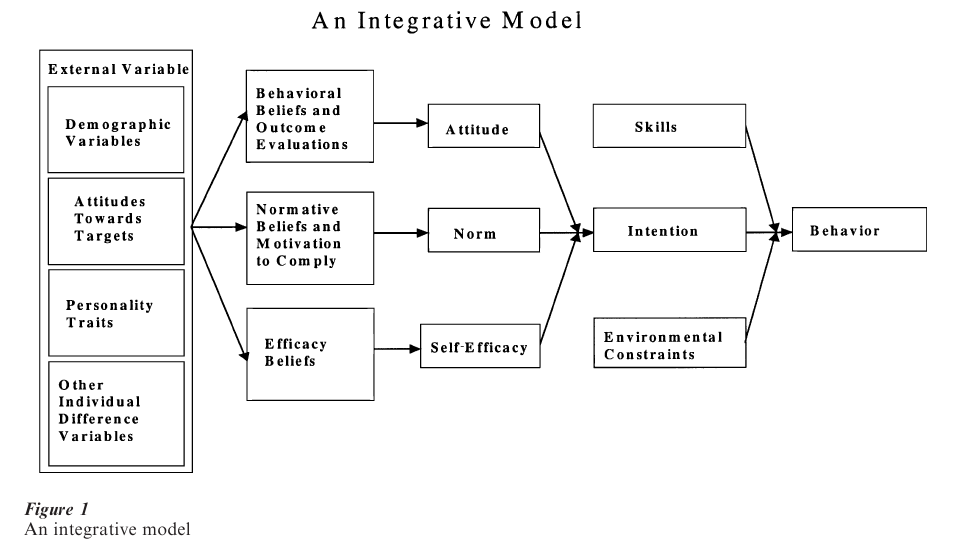

Figure 1 provides an integration of several different leading theories of behavioral prediction and behavior change (cf. Fishbein et al. 1992). Before describing this model, however, it is worth noting that theoretical models such as the one presented in Fig. 1 have often been criticized as ‘Western’ or ‘US’ models that don’t apply to other cultures or countries. When properly applied, however, these models are culturally specific, and they require one to understand the behavior from the perspective of the population being considered. Each of the variables in the model can be found in almost any culture or population. In fact, the theoretical variables contained in the model have been assessed in over 50 countries in both the developed and the developing world. Moreover, the relative importance of each of the variables in the model is expected to vary as a function of both the behavior and the population under consideration.

2.1 Determinants Of Behavior

Looking at Fig. 1, it can be seen that any given behavior is most likely to occur if one has a strong intention to perform the behavior, if one has the necessary skills and abilities required to perform the behavior, and if there are no environmental constraints preventing behavioral performance. Indeed, if one has made a strong commitment (or formed a strong intention), has the necessary skills and abilities, and if there are no environmental constraints to prevent behavioral performance, the probability is close to one that the behavior will be performed (Fishbein et al. 1992).

Clearly, very different types of interventions will be necessary if one has formed an intention but is unable to act upon it, than if one has little or no intention to perform the behavior in question. Thus, in some populations or cultures, the behavior may not be performed because people have not yet formed intentions to perform the behavior, while in others, the problem may be a lack of skills and/or the presence of environmental constraints. In still other cultures, more than one of these factors may be relevant. For example, among female commercial sex workers (CSWs) in Seattle, Washington, only 30 percent intend to use condoms for vaginal sex with their main partners, and of those, only 40 percent have acted on their intentions (von Haeften et al. 2000). Clearly if people have formed the desired intention but are not acting on it, a successful intervention will be directed either at skills building or will involve social engineering to remove (or to help people overcome) environmental constraints.

2.2 Determinants Of Intentions

On the other hand, if strong intentions to perform the behavior in question have not been formed, the model suggests that there are three primary determinants of intention: the attitude toward performing the behavior (i.e., the person’s overall feelings of favorableness or unfavorableness toward performing the behavior), perceived norms concerning performance of the behavior (including both perceptions of what others think one should do as well as perceptions of what others are doing), and one’s self-efficacy with respect to performing the behavior (i.e., one’s belief that one can perform the behavior even under a number of difficult circumstances). As indicated above, the relative importance of these three psychosocial variables as determinants of intention will depend upon both the behavior and the population being considered. Thus, for example, one behavior may be determined primarily by attitudinal considerations while another may be influenced primarily by feelings of self-efficacy. Similarly, a behavior that is driven attitudinally in one population or culture may be driven normatively in another. Thus, before developing interventions to change intentions, it is important first to determine the degree to which that intention is under attitudinal, normative, or self-efficacy control in the population in question. Once again, it should be clear that very different interventions are needed for attitudinally controlled behaviors than for behaviors that are under normative influence or are related strongly to feelings of self-efficacy. Clearly, one size does not fit all, and interventions that are successful in one culture or population may be a complete failure in another.

2.3 Determinants Of Attitudes, Norms, And Self-Efficacy

The model in Fig. 1 also recognizes that attitudes, perceived norms, and self-efficacy are all, themselves, functions of underlying beliefs—about the outcomes of performing the behavior in question, about the normative proscriptions and/or behaviors of specific referents, and about specific barriers to behavioral performance. Thus, for example, the more one believes that performing the behavior in question will lead to ‘good’ outcomes and prevent ‘bad’ outcomes, the more favorable one’s attitude toward performing the behavior. Similarly, the more one believes that specific others think one should (or should not) perform the behavior in question, and the more one is motivated to comply with those specific others, the more social pressure one will feel (or the stronger the norm) with respect to performing (or not performing) the behavior. Finally, the more one perceives that one can (i.e., has the necessary skills and abilities to) perform the behavior, even in the face of specific barriers or obstacles, the stronger will be one’s self-efficacy with respect to performing the behavior.

It is at this level that the substantive uniqueness of each behavior comes into play. For example, the barriers to using and/or the outcomes (or consequences) of using a condom for vaginal sex with one’s spouse or main partner may be very different from those associated with using a condom for vaginal sex with a commercial sex worker or an occasional partner. Yet it is these specific beliefs that must be addressed in an intervention if one wishes to change intentions and behavior. Although an investigator can sit in their office and develop measures of attitudes, perceived norms, and self-efficacy, they cannot tell you what a given population (or a given person) believes about performing a given behavior. Thus, one must go to members of that population to identify salient behavioral, normative, and efficacy beliefs. One must understand the behavior from the perspective of the population one is considering.

2.4 The Role Of ‘External’ Variables

Finally, Fig. 1 also shows the role played by more traditional demographic, personality, attitudinal, and other individual difference variables (such as perceived risk). According to the model, these types of variables primarily play an indirect role in influencing behavior. For example, while men and women may hold different beliefs about performing some behaviors, they may hold very similar beliefs with respect to others. Similarly rich and poor, old and young, those from developing and developed countries, those who do and do not perceive they are at risk for a given illness, those with favorable and unfavorable attitudes toward family planning, etc., may hold different attitudinal, normative or self-efficacy beliefs with respect to one behavior but may hold similar beliefs with respect to another. Thus, there is no necessary relation between these ‘external’ or ‘background’ variables and any given behavior. Nevertheless, external variables such as cultural and personality differences should be reflected in the underlying belief structure.

3. The Role Of Theory In HIV/STD Prevention

Models, like the one represented by Fig. 1, have served as the theoretical underpinning for a number of successful behavioral interventions in the HIV/STD arena (cf. Kalichman et al. 1996). For example, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have supported two large multisite studies based on the model in Fig. 1. The first, the AIDS Community Demonstration Projects (Fishbein et al 1999), attempted to reach members of populations at risk for HIV/STD that were unlikely to come into contact with the health department. The second, Project RESPECT, was a multisite randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of HIV/STD counseling and testing (Kamb et al. 1998). Project RESPECT asked whether prevention counseling or enhanced prevention counseling were more effective in increasing condom use and reducing incident STDs than standard education.

Although based on the same theoretical model, these two interventions were logistically very different. In one, the intervention was delivered ‘in the street’ by volunteer networks recruited from the community. In the other, the intervention was delivered one-on-one by trained counselors in an STD clinic. Thus, one involved community participation and mobilization while the other involved working within established public health settings. In addition, one was evaluated using the community as the unit of analysis while the other looked for behavior change at the individual level.

Despite these logistic differences, both interventions produced highly significant behavioral change. In addition, in the clinic setting (where it was feasible to obtain biologic outcome measures), the intervention also produced a significant reduction in incident STDs. The success of these two interventions is due largely to their reliance on established behavioral principles. More important, it appears that theory-based approaches that are tailored to specific populations and behaviors can be effective in changing STD HIV related behaviors in different cultures and communities (cf. NIH 1997).

4. The Relation Between Behavioral And Biological Outcome Measures

Unfortunately, behavior change (and in particular, self-reported behavior change), is often viewed as insufficient evidence for disease prevention, and several investigators have questioned the validity of self-reports of behavior and their utility as outcome measures in HIV/STD Prevention research. For example, Zenilman et al. (1995) investigated the relationship between STD clinic patients self-reported condom use and STD incidence. Patients coming to an STD clinic in Baltimore, Maryland, who agreed to participate in the study were examined for STDs upon entry and approximately 3 months later. At the time of the follow-up exam, participants were asked to report the number of times they had sex in the past month and the number of times they had used a condom while having sex. Those who reported 100 percent condom use were compared with those who reported sometime use or no use of condoms with respect to incident (or new) STDs.

Zenilman et al. (1995) found no significant relationship between self-reported condom use and incident STDs. Based on this finding, they questioned the veracity of the self-reports and suggested that intervention studies using self-reported condom use as the primary outcome measure were at best suspect and at worst, invalid. Such a view fails to recognize the complex relationship between behavioral and biological measures.

4.1 Transmission Dynamic Revisited

Consider again the May and Anderson (1987) model of transmission dynamics: Ro βcD. It is important to recognize that the impact on the reproductive rate, of a change in any one parameter, will depend upon the values of the other two parameters. Thus, for example, if one attempted to lower the reproductive rate of HIV by reducing transmission efficiency (either by reducing STDs or by increasing condom use), the impact of such a reduction would depend upon both the prevalence of the disease in the population and the sexual mixing patterns in that population. Clearly, if there is no disease in the population, decreases (or increases) in transmission efficiency can have very little to do with the spread of the disease. Similarly, a reduction in STD rates or an increase in condom use in those who are at low risk of exposure to partners with HIV will have little or no impact on the epidemic. In contrast, a reduction in STDs or an increase in condom use in those members of the population who are most likely to transmit and/or acquire HIV (that is, in the so-called core group), can, depending upon prevalence of the disease in the population, have a big impact on the epidemic (cf. Pequegnat et al. 2000).

To complicate matters further, it must also be recognized that changes in one parameter may directly or indirectly influence one of the other parameters. For example, at least some people have argued that an intervention program that increased condom use successfully, could also lead to an increase in number of partners (perhaps because now one felt somewhat safer). If this were in fact the case, an increase in condom use would not lead necessarily to a decrease in the reproductive rate. In other words, the impact of a given increase (or decrease) in condom use on STD HIV incidence will differ, depending upon the values of the other parameters in the model. In addition, it’s important to recognize that condom use behaviors are very different with ‘safe’ than with ‘risky’ partners. For example, condoms are used much more frequently with ‘occasional’ or ‘new’ partners than with ‘main’ or ‘regular’ partners (see e.g., Fishbein et al 1999).

Thus, one should not expect to find a simple linear relation (i.e., a correlation) between decreases in transmission efficiency and reductions in HIV seroconversions. Moreover, it should be recognized that many other factors may influence transmission efficiency. For example, the degree of infectivity of the donor; characteristics of the host; and the type and frequency of sexual practices all influence transmission efficiency; and variations in these factors will also influence the nature of a relationship between in- creased condom use and the incidence of STDs (including HIV).

In addition, although correct and consistent condom use can prevent HIV, gonorrhea, syphilis, and probably chlamydia, condoms are less effective in interrupting transmission of herpes and genital warts. Although one is always better off using a condom than not using a condom, the impact of condom use is expected to vary by disease. Moreover, for many STDs, transmission from men to women is much more efficient than from women to men. For example, with one unprotected coital episode with a person with gonorrhea, there is about a 50 to 90 percent chance of transmission from male to female, but only about a 20 percent chance of transmission from female to male.

It should also be noted that one can acquire an STD even if one always uses a condom. Consistent condom use is not necessarily correct condom use, and in-correct condom use and condom use errors occur with surprisingly high frequencies (Fishbein and Pequegnat 2000, Warner et al. 1998). In addition, at least some ‘new’ or incident infections may be ‘old’ STDs that initially went undetected or that did not respond to treatment. Despite these complexities, it is important to understand when, and under what circumstances, behavior change will be related to a reduction in STD incidence. Unfortunately, it is unlikely that this will occur until behaviors are assessed more precisely and new (or incident) STDs can be more accurately identified. From a behavioral science or psychosocial perspective, the two most pressing problems and the greatest challenges are to assess correct, as well as consistent, condom use, and to identify those at high or low risk for transmitting or acquiring STDs.

4.2 Assessing Correct And Consistent Condom Use

Condom use is most often assessed by asking respondents how many times they have engaged in sex and then asking them to indicate how many of these times they used a condom. One will get very different answers to these questions depending upon the time frame used (lifetime, past year, past 3 months, past month, past week, last time), and the extent to which one distinguishes between the type of sex (vaginal, anal, or oral) and type of partner (steady, occasional, paying client). Irrespective of the time frame, type of partner or type of sex, these two numbers (i.e., number of sex acts and number of times condoms were used) can be used in at least two very different ways. In most of the literature (particularly the social psychological literature), the most common outcome measure is the percent of times the respondent reports condom use (i.e., for each subject, one divides the number of times condoms were used by the number of sex acts).

Perhaps a more appropriate measure would be to subtract the number of time condoms were used from the number of sex acts. This would yield a measure of the number of unprotected sex acts.

Clearly, if one is truly interested in preventing disease or pregnancy, it is the number of unprotected sex acts and not the percent of times condoms are used that should be the critical variable. Obviously, there is a difference in one’s risk of acquiring an STD if one has sex 1,000 times and uses a condom 900 times than if one has sex 10 times and uses a condom 9 times. Both of these people will have used a condom 90 percent of the time, but the former will have engaged in 100 unprotected sex acts while the latter will have engaged in only 1.

By considering the number of unprotected sex acts rather than the percent of times condoms are used, it becomes clear how someone who reports always using a condom can get an STD or become pregnant. To put it simply, consistent condom use is not necessarily correct condom use, and incorrect condom use almost always equates to unprotected sex.

4.3 How Often Does Incorrect Condom Use Occur?

There is a great deal of incorrect condom use. For example, Warner et al. (1998) asked 47 sexually active male college students (between 18 and 29 years of age) to report the number of times they had vaginal intercourse and the number of times they used condoms in the last month. In addition the subjects were asked to quantify the number of times they experienced several problems (e.g., breakage, slippage) while using condoms. Altogether, the 47 men used a total of 270 condoms in the month preceding the study. Seventeen percent of the men reported that intercourse was started without a condom, but they then stopped to put one on; 12.8 percent reported breaking a condom during intercourse or withdrawal; 8.5 percent started intercourse with a condom, but then removed it and continued intercourse; and 6.4 percent reported that the condom fell off during intercourse or withdrawal. Note that all of these people could have honestly reported always using a condom, and all could have transmitted and/or acquired an STD!

Similar findings were obtained from both men and women attending STD clinics in the US (Fishbein and Pequegnat 2000). For example, fully 34 percent of women and 36 percent of men reported condom breakage during the past 12 months, with 11 percent of women and 15 percent of men reporting condom breakage in the past 3 months. Similarly, 31 percent of the women and 28 percent of the men reported that a condom fell off in the past 12 months while 8 percent of both men and women report slippage in the past 3 months. Perhaps not surprisingly women are significantly more likely than men to report condom leakage (17 percent vs. 9 percent). But again, the remarkable findings are the high proportion of both men and women reporting different types of condom mistakes. For example, 31 percent of the men and 36 percent of the women report starting sex without a condom and then putting one on, while 26 percent of the men and 23 percent of the women report starting sex with a condom and then taking it off and continuing intercourse. This probably reflects the difference between using a condom for family planning purposes and using one for the prevention of STDs including HIV.

The practice of having some sex without a condom probably reflects incorrect beliefs about how one prevents pregnancy. Irrespective of the reason for these behaviors, the fact remains that all of these ‘errors’ could have led to the transmission and/or acquisition of an STD despite the fact that condoms had, in fact, been used.

In general, and within the constraints of one’s ability to accurately recall past events, people do appear to be honest in reporting their sexual behaviors including their condom use. Behavioral scientists must obtain better measures, not of condom use per se, but of correct and consistent condom use, or perhaps even more important, of the number of unprotected sex acts in which a person engages.

4.4 Sex With ‘Safe’ And ‘Risky’ Partners

Whether one uses a condom correctly or not is essentially irrelevant as long as one is having sex with a safe (i.e., uninfected) partner. However, to prevent the acquisition (or transmission) of disease, correct and consistent condom use is essential when one has sex with a risky (i.e., infected) partner. Although it is not possible to always know whether another person is safe or risky, it seems reasonable to assume that those who have sex with either a new partner, an occasional partner, or a main partner who is having sex outside of the relationship are at higher risk than those who have sex only with a main partner who is believed to be monogamous. Consistent with this, STD clinic patients with potential high risk partners (i.e., new, occasional, or nonmonogamous main partners) were significantly more likely to acquire an STD than those with potential low risk partners (18.5 percent vs. 10.4 percent; Fishbein and Jarvis 2000).

One can also assess people’s perceptions that their partners put them at risk for acquiring HIV. For example, the STD clinic patients were also asked to indicate, on seven-place likely (7) unlikely (1) scales, whether having unprotected sex with their main and/or occasional partners would increase their chances of acquiring HIV. Not surprisingly those who felt it was likely that unprotected sex would increase their chances of acquiring HIV (i.e., those with scores of 5, 6, or 7) were, in fact, significantly more likely to acquire a new STD (19.4 percent) than those who perceived that their partner(s) did not put them at risk (i.e., those with scores of 1, 2, 3, or 4—STD incidence = 12.6 percent).

Somewhat surprising, clients’ perceptions of the risk status of their partners were not highly correlated with whether they were actually with a potentially safe or dangerous partner (r = .11, p < .001). Nevertheless, both risk scores independently relate to STD acquisition. More specifically, those who were ‘hi’ on both actual and perceived risk were almost four times as likely to acquire a new STD than were those who are ‘lo’ on both actual and perceived risk. Those with mixed patterns (i.e., hi/lo or lo/hi) are intermediate in STD acquisition (Fishbein and Jarvis 2000). So, it does appear possible to not only find behavioral measures that distinguish between those who are more or less likely to acquire a new STD, but equally important, it appears possible to identify measures that distinguish between those who are, or are not, having sex with partners who are potentially placing them at high risk for acquiring an STD.

4.5 STD Incidence As A Function Of Risk And Correct And Consistent Condom Use

If this combined measure of actual and perceived risk is ‘accurate’ in identifying whether or not a person is having sex with a risky (i.e., an infected) or a safe (i.e., a noninfected) partner, condom use should make no difference with low-risk partners, but correct and consistent condom use should make a major difference with high-risk partners. More specifically, correct and consistent condom use should significantly reduce STD incidence among those having sex with potential high-risk partners. Consistent with this, while condom use was unrelated to STD incidence among those with low-risk partners, correct and consistent condom use did significantly reduce STD incidence among those at high risk. Not only are these findings important for understanding the relationship between condom use and STD incidence but they provide evidence for both the validity and utility of self-reported behaviors. In addition, these data provide clear evidence that if behavioral interventions significantly increase correct and consistent condom use among people who perceive they are at risk and/or who have a new, an occasional, or a nonmonogamous main partner, there will be a significant reduction in STD incidence. On the other hand, if, among this high-risk group, we only increase consistency of use without increasing correct use and/or if we only increase condom use among those at low risk, then we will see little or no reduction in STD (or HIV) incidence.

5. Future Directions

Clearly it is time to stop using STD incidence as a ‘gold standard’ to validate behavioral self-reports and to start paying more attention to understanding the relationships between behavioral and biological outcome measures. It is also important to continue to develop theory-based, culturally sensitive interventions to change a number of STD/HIV related behaviors. While much of the focus to date has been on increasing consistent condom use, interventions are needed to increase correct condom use and to increase the likelihood that people will come in for screening and early treatment, and, for those already infected, to adhere to their medical regimens. Indeed, it does appear that we now know how to change behavior, and that under appropriate conditions, behavior change will lead to a reduction in STD incidence. While many investigators have called for ‘new’ theories of behavior change, ‘new’ theories are probably unnecessary. What is needed, however, is for investigators and interventionists to better understand and correctly utilize existing, empirically supported theories in developing and evaluating behavior change interventions.

Bibliography:

- Aral S O, Holmes K K 1999 Social and behavioral determinants of the epidemiology of STDs: Industrialized and developing countries. In: Holmes K K, Sparling P F, Mardh P-A, Lemon S M, Stamm W E, Piot P, Wasserheit J N (eds.) Sexually Transmitted Diseases. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Fishbein M, Higgins D L, Rietmeijer C 1999 Community-level HIV intervention in five cities: Final outcome data from the CDC AIDS community demonstration projects. American Journal of Public Health 89(3): 336–45

- Fishbein M, Bandura A, Triandis H C, Kanfer F H, Becker M H, Middlestadt S E 1992 Factors Influencing Behavior and Behavior Change: Final Report—Theorist’s Workshop. National Institute of Mental Health, Rockville, MD

- Fishbein M, Jarvis B 2000 Failure to find a behavioral surrogate for STD incidence: What does it really mean? Sexually Transmitted Diseases 27: 452–5

- Fishbein M, Pequegnat W 2000 Using behavioral and biological outcome measures for evaluating AIDS prevention interventions: A commentary. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 27(2): 101–10

- Kalichman S C, Carey M P, Johnson B T 1996 Prevention of sexually transmitted HIV infection: A meta-analytic review of the behavioral outcome literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 18(1): 6–15

- Kamb M L, Fishbein M, Douglas J M, Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, Zenilman J, Hoxworth T, Mallotte C K, Iatesta M, Kent C, Lentz A, Graziano S, Byers R H, Peterman T A, the Project RESPECT Study Group 1998 HIV/STD prevention counseling for high-risk behaviors: Results from a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 280(13): 1161–7

- May R M, Anderson R M 1987 Transmission dynamics of HIV infection. Nature 326: 137–42

- NIH Consensus Development Panel 1997 Statement from consensus development conference on interventions to prevent HIV risk behaviors. NIH Consensus Statement 15(2): 1–41

- Pequegnat W, Fishbein M, Celantano D, Ehrhardt A, Garnett G, Holtgrave D, Jaccard J, Schachter J, Zenilman J 2000 NIMH/APPC workgroup on behavioral and biological outcomes in HIV/STD prevention studies: A position statement. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 27(3): 127–32

- von Haeften I, Fishbein M, Kaspryzk D, Montano D 2000 Acting on one’s intentions: Variations in condom use intentions and behaviors as a function of type of partner, gender, ethnicity and risk. Psychology, Health & Medicine 5(2): 163–71

- Warner L, Clay-Warner J, Boles J, Williamson J 1998 Assessing condom use practices: Implications for evaluating method and user eff Sexually Transmitted Disases 25(6): 273–7

- Zenilman J M, Weisman C S, Rompalo A M, Ellish N, Upchurch D M, Hook E W, Clinton D 1995 Condom use to prevent incident STDs: The validity of self-reported condom use. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 22(1): 15–21