Sample Melanesia Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

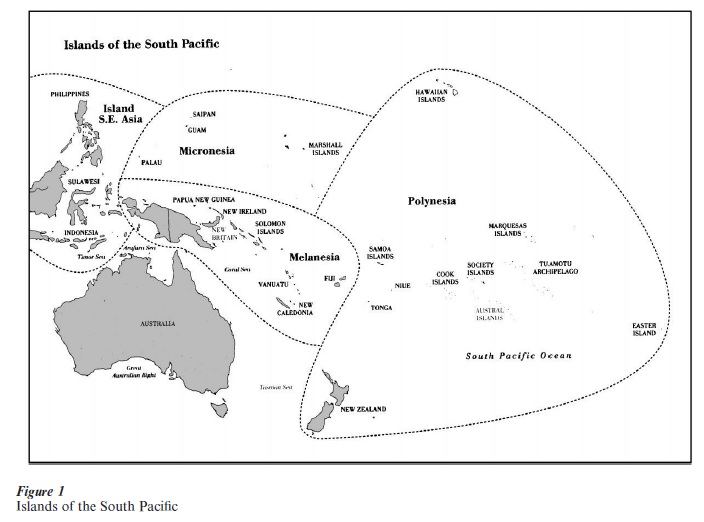

The convention of dividing Oceania into three distinct geographic regions or culture areas—Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia—originated in 1832 with the French navigator J-C-S. Dumont d’Urvilles. By this convention, Melanesia today encompasses the independent nation-states of Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and Fiji; the French overseas territory of New Caledonia (Kanaky); the Indonesian province of Irian Jaya or Papua (West Papua); and the Torres Straits Islands, part of the Australian state of Queensland. These islands comprise about 960,000 square kilometers with a total population of more than eight million people. The large island of New Guinea and its smaller offshore islands account for almost 90 percent of the land area and 80 percent of the population of Melanesia (see Fig. 1).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Melanesian Diversities

The diversity of contemporary Melanesian political arrangements is exceeded by a linguistic, cultural, ecological, and biological diversity that impressed early European explorers and challenged later social and natural scientists. Although mostly pig-raising root-crop farmers, Melanesians occupy physical environments ranging from montane rainforests to lowland river plains to small coral islands; they live in longhouses, nucleated villages, dispersed hamlets, and urban settlements. While racially stereotyped as blackskinned and woolly-haired people, they display a wide range of phenotypic features. Similarly, Melanesian social organizations illustrate numerous anthropologically recognized possibilities with respect to rules of descent, residence, marriage, and kin terminology. Melanesians speak more than 1,100 native languages, some with tens of thousands of speakers and others with less than a few hundred. English, French, and Bahasa Indonesia are recognized as official languages; several pidgin-creoles are widely spoken and also recognized as official languages in Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu. Melanesia is thus culturally heterogeneous to the point that its very status as a useful ethnological category is dubious; many anthropologists would assign Fiji to Polynesia and classify Torres Straits Islanders with Australian Aborigines. Ethnographic generalizations about the region often show a marked bias toward cases from some areas (e.g., the New Guinea Highlands) rather than others (e.g., southcoast New Guinea), and in any case remain rare.

Linguists, archeologists, and geneticists offer persuasive narratives of prehistoric migrations that account for Melanesian heterogeneity. These narratives, although not universally accepted, reveal how Dumont D’Urvilles’ convention obscures historical and cultural connections between Melanesian and other Pacific populations as well as fundamental differences within Melanesian populations. At least 40,000 years ago, human populations of hunter– gatherers settled the super-continent of Sahul (Australasia), reaching what is today the island of New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon chain by at least 30,000 years ago. Linguistic evidence suggests that these settlers spoke NonAustronesian (NAN or Papuan) languages, which today number around 750 and occur mainly in the interior of New Guinea, with isolated instances through the islands to the east as far as the Santa Cruz Archipelago. By 3,500 years ago, a second migration out of Southeast Asia had brought another population into sustained contact with the original settlers of the Bismarcks. This migration is associated by archeologists with the distinctive Lapita pottery complex, distribution of which suggests that ‘Lapita peoples’ had by 3,000 years ago moved as far south and east as hitherto uninhabited Fiji and western Polynesia. Lapita peoples spoke an early language of the Austronesian (AN or Malayo-Polynesian) family labeled Proto-Oceanic. Austronesian languages are today distributed along coastal eastern New Guinea and through island Melanesia; all Polynesian languages and most Micronesian ones are also descended from Proto-Oceanic. Hence the extraordinary linguistic, cultural, and biological diversity of Melanesia by comparison with Polynesia and Micronesia derives from at least two prehistoric sources: (a) processes of divergence and differentiation among relatively separated populations over the very long period of human occupation in the region, especially on the island of New Guinea, and (b) processes of mixing or creolization between the original NAN-speaking settlers and the later AN-speaking arrivals in island Melanesia.

2. Social and Cultural Anthropology in of Melanesia

Dumont D’Urvilles’ classificatory legacy has been provocatively criticized on different grounds, namely that ‘Melanesia’ often designates one term of an invidious comparison with ‘Polynesia.’ Such comparisons, manifestly racist in many nineteenth-century versions, portray Melanesians as economically, politically, and culturally less developed than Polynesians and, by evolutionary extension, people of ‘the West.’ To Western political and economic interests, moreover, Melanesia has historically appeared marginal; Melanesianist anthropologists, for example, never found much support within the post World War II institutional apparatus of area studies. This marginality has rendered Melanesian studies as the exemplar of anthropology’s authoritative discourse on ‘primitives,’ and contributed to the popular perception of Melanesian studies as the anthropological subfield most engaged in the contemporary study of radical (non-Western) Otherness. Such a perception not only turns Melanesian people into exotic vehicles for Western fantasy, but also suppresses the continuing history of colonialism in the region and misrepresents much Melanesianist anthropology, past and especially present.

Melanesian ethnography has played a central role in the history of the larger discipline’s methods and theories. The work of W. H. R. Rivers on the 1898 Cambridge Expedition to the Torres Straits and later trips to Melanesia, and of Bronislaw Malinowski during his World War I era research in the Trobriand Islands, both mark important moments in the development of genealogical inquiry and extended participant observation as characteristic methods of social anthropology. Similarly, the Melanesian ethnography of M. Mead, G. Bateson, R. Fortune, and I. Hogbin, among others, guided anthropological approaches to questions of socialization and emotions, culture and personality, gender relations and sorcery, ritual process and social structure. From 1950 onwards, anthropology drew heavily on Melanesian ethnography— including the first waves of intensive fieldwork in the New Guinea Highlands—for diverse theoretical advances in the areas of cultural ecology, gender and sexuality, and in the study of metaphor, meaning, and knowledge transmission.

3. Gift Commodity

Most prominent among the gate-keeping concepts that make Melanesia a distinctive anthropological place is exchange. Malinowski’s classic description of kula, and Marcel Mauss’s treatment of Malinowski’s ethnography in The Gift, provided the grounds for understanding Melanesian sociality as fluid and contingent, performed through pervasive acts of give and take. In the 1960s, the critique of models of segmentary lineage structure in the New Guinea Highlands further enabled recognition of reciprocity and exchange as the Melanesian equivalents of the principle of descent in Africa. Exchange brings into being the social categories that it perforce defines and mediates: affines and kin, men and women, clans and lineages, friends and trade partners, living descendants and ancestral spirits. The rhythms of Melanesian sociality thus develop out of infrequent large-scale prestations associated with collective identities and male prestige; occasional gifts of net bags from a sister to her brother or of magic from a maternal uncle to his nephew; and everyday exchanges of cooked food between households and betel nut between companions.

Before contact with Westerners, Melanesia was laced by extensive trade networks that connected coastal and inland areas, and linked numerous islands and archipelagoes. These regional networks crossed different ecological zones and organized the specialized production of food, pigs, crafts, and rare objects of wealth such as pearl shells and bird plumes. Wealth objects were in turn often displayed and circulated in sequential chained exchanges, of which the most complex and geographically far-reaching include kula, and the Melpa moka and Enga tee systems of the central New Guinea Highlands. These exchange systems often define a sphere of male-dominated activity that depends on the labor of women, but instances of women circulating women’s wealth in public exchanges do occur throughout Melanesia. During the colonial period, many trade networks atrophied, while other forms of competitive exchange effloresced, incorporating new items of wealth. State-issued money now commonly circulates in exchange alongside indigenous currencies and wealth, especially as part of marriage payments and homicide compensations.

Melanesians sometimes self-consciously contrast their own reciprocal gift-giving with the market transactions of modern Western society; for example, the distinction between kastam (‘custom’) and bisnis (‘business’) occurs in the English-based pidgin-creoles of the region. In related fashion, anthropologists have used an ideal–typical contrast between a gift economy and a commodity economy to describe the social relations of reproduction characteristic of indigenous Melanesia. For Gregory (1982), ‘gift reproduction’ involves the creation of personal qualitative relationships between subjects transacting inalienable objects, including women in marriage; and ‘commodity reproduction’ involves the creation of objective quantitative relationships between the alienable objects that subjects transact. This dichotomy provides a way of talking about situations now common in Melanesia in which the status of an object as gift or commodity changes from one social context to another, and varies from one person’s perspective to another. Such situations occur, for example, when kin-based gift relations become intertwined with the patronage system associated with elected political office or when marriage payments become inflated by cash contributions derived from wage labor and the sale of coffee and copra.

While Gregory’s formulation has been criticized as obscuring the extent to which commodity-like transactions—barter, trade, localized markets—were always a feature of Melanesian social life (and gifts a feature of highly commoditized Western societies), it nonetheless highlights how Melanesians produce crucial social relations out of the movement of persons and things. Anthropologists have thus used the concept of personhood as a complement to the concept of the gift in understanding Melanesian moral relationships; for it is in the context of gift exchange that the agency of persons and the meaning of things appear most clearly as the effects of coordinated intentions. Marilyn Strathern contrasts a Melanesian relational person or dividual with a Western individual. Whereas Western individuals are discrete, distinct from and prior to the social relations that unite them, Melanesian dividuals are composite, the site of the social relations that define them. Similarly, whereas the behavior of individuals is interpreted as the external expression of internal states (e.g., anger, greed, etc.), the behavior of dividuals is interpreted in terms of other people’s responses and reactions. The notion of dividuality makes sense of many Melanesian life-cycle rites that recognize the contributions of various kin to a person’s bodily growth, as well as of mythological preoccupations with the management of ever-labile gender differences.

4. Equality Hierarchy

Melanesian polities have often been characterized as egalitarian relative to the chiefly hierarchies of Polynesia; instances of ascribed leadership and hereditary office, numerous throughout insular Melanesia, have accordingly been regarded as somewhat anomalous, while the categorical distinction between ‘chiefs’ and ‘people of the land’ has served to mark Fiji’s problematic inclusion within Melanesia. Traditional Melanesian political organization has been defined negatively, as not only stateless but also lacking any permanent form capable of defining largescale territorial units. Precolonial warriors, such as those of south-coast New Guinea, distinguished themselves through vigorous practices of raiding, headhunting, and cannibalism that ensured social and cosmological fertility. Local autonomy, armed conflict, and ongoing competition among men for leadership have thus been taken as the hallmarks of traditional Melanesian politics. This definition of precolonial Melanesian polities invokes a sharp contrast with the centralized, bureaucratic, violencemonopolizing states of the West. Yet, at the same time, Melanesian politics, epitomized in the figure of the self-made ‘big man,’ have sometimes been thought to recall values of individualism and entrepreneurship familiar from the West’s own self-image.

Big men typically validate their personally achieved leadership through generous distributions of wealth. They manipulate networks of reciprocal exchange relationships with other men, thus successfully managing the paradox of generating hierarchy—even if only temporarily—out of equality. This paradox is variously expressed within Melanesia. In classic bigman exchange systems, known best from areas of high population density and intensive pig husbandry and horticulture in the New Guinea Highlands (Melpa, Enga, Simbu, Dani), a constant and imbalanced flow of shells, pigs, and money underwrites individual

prestige. Such systems are not found everywhere in Melanesia, however, prompting Godelier (1986) to invent a new personification of power, the ‘great man.’ Great men emerge where public life turns on ritual initiations, where marriage involves the direct exchange of women (‘sister exchange’), and where warfare once similarly prescribed the balanced exchange of homicides. The prestige and status of great men often depends upon their success in keeping especially valued ‘inalienable possessions’ out of general circulation. While this typological innovation has been challenged, political life in the Sepik area and in eastern Melanesia frequently involves transmitting ritual resources (heirlooms, myths, names, and so forth) within a delimited kin grouping such as a clan. In the Mountain Ok area, ancestral relics (bones and skulls) provide the material focus of a secret men’s cult that links contiguous communities and complements clan affairs; in insular Melanesia, forms of voluntary male political association detached from kin groupings are found, such as the public graded societies of northern Vanuatu. Nevertheless, the scope for establishing political relations in precolonial Melanesia was restricted by the instability of big men’s exchange relations, or by the demands placed on high-ranking men to sponsor youthful aspirants, or by the limited extent of the communities or kin groups beyond which ritual resources have no currency.

Whereas Melanesian political relations have been deemed egalitarian by comparison with the West, gender relations have usually been characterized as manifestly inegalitarian. Ethnography of highlands New Guinea in particular suggests that women’s productive labor in gardening and pig husbandry is eclipsed if not wholly appropriated by men who act exclusively as transactors in public exchanges. In areas with once secret and lengthy rites of male initiation, senior men socialized boys into ideologies of dangerous female power and pollution while enforcing strict physical separation of the sexes. Ethnography of insular Melanesia (AN speakers), by contrast, suggests that gender inequality is less severe, tempered by women’s social and genealogical roles as sisters rather than wives, and as both producers and transactors of cosmologically valued wealth items such as finely woven mats. But Margaret Mead’s pioneering work on sex and temperament in the Sepik area, and Knauft’s (1993) review of south-coast New Guinea ethnography suggest the extreme variation possible in gender relations among even geographically proximate societies.

New forms of social inequality and hierarchy have taken shape since the mid-nineteenth century through intensified interactions with foreign traders, missionaries, and government officials. During the colonial period, ‘chiefs’ were often appointed in areas where they had not existed, while indigenously recognized leaders were often able to use their status to monopolize access to the expanding cash economy.

Male labor migration put extra burdens on women who remained at home, their contacts with new ideas and values inhibited. In rural areas today, ‘rich peasants’ have emerged by manipulating customary land tenure—and sometimes using ‘development’ funds of the postcolonial state—to accumulate smallholdings of cash crops; conflicts have arisen over claims to cash crops that women raise on land owned by their husbands. In urban areas, political and economic elites attempt to reproduce their dominant class position through private education and overseas investments as well as cosmopolitan consumption practices.

5. Melanesian Modernities

The legacies of different colonial states (Great Britain, France, Germany, The Netherlands, Australia, and Indonesia) variously condition Melanesian political economies, especially with regard to control of land. In Papua New Guinea, limited land alienation by the crown, an indirect subsidy of contract labor, has preserved a vital resource in the defense against encroaching commodification; but French settlers in New Caledonia and, more recently, Javanese transmigrants in Irian Jaya violently displaced indigenous populations. In Fiji, complicated arrangements for leasing agricultural land, a consequence of British colonial policy, generate tension between Fijian landowners and their largely Indo-Fijian tenants, descendants of indentured plantation workers brought from India in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In addition, uneven capitalist markets and proliferating Christian denominations have added new dimensions to the diversity of Melanesia. Anthropologists readily acknowledge that even in those parts of Melanesia where the presence of foreign agents and institutions has been relatively weak (once a tacit justification for rendering colonial entanglements ethnographically invisible), received cultural orientations have become articulated with globalized elements of Western modernity. In other words, Melanesia is emerging as a key anthropological site for the comparative study of plural or local modernities. Current Melanesianist research, historical as well as ethnographic, extends earlier studies of north-coast New Guinea cargo cults that sought to demonstrate how indigenous cosmologies shaped local interpretations of European material wealth and religious culture. This research highlights the syncretic products of intercultural encounters, noting how Melanesians have appropriated and reinterpreted such notable ideological imports as Christianity, millenarian and otherwise, and democracy. Even the impact of largescale mining and timber projects has been shown to be mediated by highly local understandings of land tenure, kinship, and moral economy. In West Papua and Papua New Guinea, these projects define sites of struggle among transnational corporations, national states, and local stakeholders, often generating destructive environmental consequences (the Ok Tedi and Grasberg gold mines) and massive social dislocation (the civil war on Bougainville).

By the same token, current research emphasizes how the historical encounter with Western agents and institutions often transforms indigenous social practices, including language socialization, thus revaluing the meaning of tradition. For example, the flourishing gift economies of rural villagers are often a corollary of the remittances sent back by wage workers in town, while the ritual initiation of young boys might provide a spectacle for paying tourists from Europe and the USA. Since the 1970s, the emergence of independent nation-states has stimulated attempts to identify national traditions with habits such as betel-nut chewing or artifacts such as net bags, both of which have become much more geographically widespread since colonization. In many of these states, ‘chieftainship’ furnishes the newly traditional terms in which elected political leaders compete for power and resources. In New Caledonia, the assertion of a unifying aboriginal (Kanak) identity and culture has been a feature of collective anticolonial protest.

Contemporary Melanesian societies and cultures are thus defined by a tense double process. On the one hand, they are increasingly drawn into a world system through the spread of commercial mass media; the force of economic reforms mandated by interstate regulatory agencies; and the sometimes tragic exigencies of creating political communities on the global model of the nation-state. On the other hand, they continue to reproduce themselves in distinctive and local ways, organizing processes of historical change in terms of home-grown categories and interests.

Bibliography:

- Douglas B 1998 Across the Great Di ide: Journeys in History and Anthropology. Harwood Academic Publishers, Amsterdam

- Foster R J (ed.) 1995 Nation Making: Emergent Identities in Postcolonial Melanesia. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- Gewertz D B, Errington F K 1999 Emerging Class in Papua New Guinea: The Telling of Difference. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Godelier M 1986 The Making of Great Men: Male Domination and Power Among the New Guinea Baruya [trans. Swyer R]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Gregory C A 1982 Gifts and Commodities. Academic Press, New York

- Jolly M 1994 Women of the Place: Kastom, Colonialism and Gender in Vanuatu. Harwood Academic Publishers, Philadelphia

- Kirch P V 1997 The Lapita Peoples: Ancestors of the Oceanic World. Blackwell, Cambridge, MA

- Knauft B M 1993 South Coast New Guinea Cultures: History, Comparison, Dialectic. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Knauft B M 1999 From Primiti e to Postcolonial in Melanesia and Anthropology. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- Kulick D 1992 Language Shift and Cultural Reproduction: Socialization, Self and Syncretism in a Papua New Guinea Village. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Lederman R 1998 Globalization and the future of culture areas: Melanesianist anthropology in transition. Annual Re iew of Anthropology 27: 427–49

- Pawley A 1981 Melanesian diversity and Polynesian homogeneity: A unified explanation for language. In: J Hollyman, A Pawley (eds.) Studies in Pacific Languages & Cultures in Honour of Bruce Biggs. Linguistic Society of New Zealand, Auckland, NZ, pp. 269–309

- Spriggs M 1997 The Island Melanesians. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Strathern M 1988 The Gender of the Gift: Problems with Women and Problems with Society in Melanesia. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Weiner A B 1992 Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping-While-Gi ing. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA