Sample Theory Of Principles And Parameters Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

In generative syntax principles and parameters are two related concepts introduced to capture both invariance of language and cross-linguistic variation. Principles express universal constraints on language; parameters define the space of cross-linguistic variation.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Background: The Problem Of Language Acquisition

The goal of generative linguistics is that of developing a model of linguistic knowledge (Chomsky 1981a, 1981b, 1986), i.e., to describe the cognitive system at the basis of the language capacity.

1.1 Knowledge Of Language

Linguistic knowledge is represented as a system of constraints, a grammar, which defines all and only the possible sentences of the language (Emonds 1980, Ross 1967, Perlmutter 1971). An adequate grammar of a specific language must not generate ungrammatical sentences, i.e., sentences which are not acceptable to the native speakers of that language. For instance, the grammar of English will generate (1a) and must not generate (1b).

(1a) John always eats chocolate.

(1b) *John eats always chocolate.

1.2 Language Acquisition

The generative linguist also poses the question of language acquisition. Linguistic knowledge is acquired fast and at an early age. This leads to the hypothesis that the system underlying it must be relatively simple. The speed and ease of language acquisition is all the more striking because it is achieved on the basis of an input which is deficient in several respects:

(a) The linguistic input is not homogeneous but varies from one learner to the other.

(b) The input contains ungrammatical material (performance errors, hesitations).

(c) The child acquires linguistic knowledge which he or she cannot infer solely on the basis of the input.

The following illustration of this so-called ‘negative evidence’ problem is from White (1989). In each sentence, the subordinating conjunction that may be omitted.

(2) I think (that) John will leave.

(3) Who do you think (that) John will invite?

(4) The woman (that) you met last week is my sister.

If data such as (2)–(4) constitute the input for the acquisition process, the child will be entitled to infer generalization (5).

(5) The subordinating conjunction that may be omitted in English.

However, the subordinating conjunction that cannot always be omitted in English (6, 7), and, conversely, there are sentences in which that is ungrammatical (8). (6a) That Mary should be invited is surprising.

(6b) *Mary should be invited is surprising.

(7a) She could not get over the fact that Mary was invited.

(7b) *She could not get over the fact Mary was invited.

(8a) *Who did you say that got there first?

(8b) Who did you say got there first?

How does the native speaker acquire the knowledge that (6b), (7b), and (8a) are not acceptable English sentences, while (6a), (7a), and (8b) are acceptable? All the sentences in (6), (7), and (8), including (6b), (7b), and (8a), are compatible with (5). Being ungrammatical, (6b), (7b), and (8a) are not available in the input. The input contains sentences such as (6a), (7a), and (8b), which are all compatible with (5). For the native speaker to infer that (6b), (7b), and (8a) are incompatible with English grammar, and that (5) is thus an incorrect generalization, the input would have to contain negative evidence, i.e., the information that (6b), (7b) and, (8a) are ungrammatical. Such negative evidence is not available in the input: the non- occurrence of example such as (6b), (7b), and (8a) in the input is not sufficient to establish their ungrammaticality. A pattern may be absent from the input because it is ungrammatical (e.g., (1b)), but it may also be absent because it is stylistically marked.

The deficiency of the input leads to the hypothesis that language acquisition is not based simply on exposure.

2. Universal Grammar: Principles And Parameters

The hypothesis was formulated that a theory of language acquisition must assume a genetically-determined language acquisition device, which mediates between the data in the input and the grammar of the language which the child is to attain. In the Principles and Parameters Theory (Chomsky 1981a, 1981b, 1986) abstract universal principles which underlie different linguistic patters are factored out and attributed to Universal Grammar (UG), the innate language faculty. UG guides language acquisition by constraining the possible grammars which can be formulated on the basis of the input. Two types of UG principles are distinguished: invariant principles (see Sect. 3) and parameterized principles (see Sect. 4).

Invariant principles are rigidly fixed and hold universally. For instance, the Empty Category Principle constrains omission of constituents in a sentence. Hence, the application of generalization (5), inferred from the input, is constrained by the Empty Category Principle. Other invariant principles are those which impose constraints on syntactic structure (see Sect. 3), and the (still controversial) principle that all syntactic variation is driven by morphological variation (see Sect. 5).

Other principles of UG are not fully fixed cross-linguistically; their interaction with the input will be at the basis of cross-linguistic variation. The variable components of UG are referred to as ‘parameters.’ Parameters are binary: each parameter offers a choice between two options or parameter-settings. Depending on the parameter-setting, a language will or will not display the corresponding syntactic property. For example, the pro-drop parameter determines whether a subject pronoun may be omitted in a given language or not (Sect. 4.1), the verb-movement parameter determines if a verb can be separated from its direct object (Sect. 4.2).

The principles and parameters theory thus captures cross-linguistic invariance (in terms of the universal constraints), and cross-linguistic variation (in terms of the language-specific parameter-settings). The theory reduces acquisition of syntax to parameter-setting on the basis of the linguistic input, the so-called ‘triggering experience.’

3. Invariant Principles: Phrase Structure Is Endocentric And Binary Branching

According to one invariant principle of grammar, syntactic structure is characterized by two properties:

(a) structure is endocentric: a syntactic unit or a constituent is organized around a head; and

(b) constituents are always formed by combining two units.

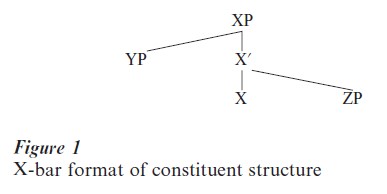

Based on (a) and (b), all constituents have the binary branching format represented in Fig. 1, where XP is the constituent, X is its head. The head X combines with another constituent, here ZP. ZP is itself built according to the X-bar format. The unit formed by X and ZP (X ) combines with the constituent YP to form XP. The format in Fig. 1 is taken to be universal. Cross-linguistic variation in sentence patterns is determined either by the option of omitting certain constituents (cf. Sect. 4.1) or by moving them (cf. Sect. 4.2).

4. Parameters

4.1 The Pro-Drop Parameter

In terms of the X-bar format in Fig. 1 the sentence is conceived of as a constituent whose head is the inflection of the verb (I).

The pro-drop parameter (see Fig. 2) determines the variation between languages like Italian, in which the subject pronoun can be omitted, and those like English, in which it cannot be omitted (Jaeggli and Safir 1986, Rizzi 1986).

(9a) Parla inglese. (Italian)

(9b) *Speaks English.

The pro-drop parameter is formulated in terms of the relative richness of the verbal inflection. The inflectional paradigm of the Italian is rich: it has a distinct form for each person number combination (parlo, parli, parla, parliamo, parlate, parlano, ‘speak,’ present tense). English inflection is poor, with minimal variation (speak, speaks). Rich inflection sets the pro- drop parameter positively, allowing the language in question to omit subject pronouns.

The concept of parameter should not be taken to mean that each aspect of cross-linguistic variation is related to a distinct parameter. A parameter underlies a cluster of properties. For instance, it is generally held that the pro-drop also underlies the contrasts in (10)–(12). As shown by (10), Italian weather verbs such as rain cannot have a subject, while English weather verbs must have a subject. While (11) shows that the subject may follow the verb in Italian, an option unavailable in English. Questioning the subject of a subordinate sentence in Italian (12a) is compatible with the presence of the conjunction che, while the English analogue in (12b) is unacceptable; (12b) is rendered grammatical by omitting that (cf. (8b)).

(10a) Piove./*Esso piove.

(10b) *Is raining. It is raining.

(11a) Arriva Gianni.

(11b) *Arrives John.

(12a) Chi credi che abbia telefonato?

(12b) *Who do you believe that has phoned?

4.2 Verb Movement

The distribution of verbs in the clause provides a second illustration for the interaction between verb morphology and syntactic variation. In English (13a), the inflected verb eats immediately precedes the direct object chocolate. The verb follows the adverb often. In French (13b), the finite verb is separated from its direct object du chocolat and it precedes the adverb souvent.

(13a) John often eats chocolate.

(13b) Jean mange souvent du chocolat. (French)

*John eats often chocolate.

The verb and its direct object form a semantic unit. While the English verb in (13a) remains adjacent to its object, the French verb mange in (13b) is separated from the object. Based on the structure in Fig. 2 it is proposed that French (13b) involves leftward verbmovement from the position V to the inflectional head (I).

The contrast between Icelandic and Danish in (14) is the same as that between English and French in (13). The Danish verb remains adjacent to its object; the Icelandic verb is separated from its object by the adverb oft.

(14a) at Johan often spiser tomater. (Danish) that John often eats tomatoes.

(14b) a Jon bor ar oft tomata. (Icelandic) *that John eats often tomatoes.

Verb-movement, as displayed by French (13b) and by Icelandic (14b), is also related to the inflectional paradigm of the verb (Pollock 1989, Holmberg and Platzack 1995). French and Icelandic have a relatively rich inflection, whereas English and Danish have impoverished inflection. In languages with rich inflection, the verb can move away from its direct object.

The kind of paradigm which allows verb movement is related but not identical to the kind of paradigm which triggers a positive setting of the pro-drop parameter as discussed in Sect. 4.1. Verb-movement to the inflectional head requires fewer distinct forms in the paradigm than pronoun omission (cf. Vikner 1997, pp. 192ff .). Verb-movement is possible in languages like French or Icelandic which do not allow the subject pronoun to be omitted.

5. Parameters And Language Acquisition

The parameter determining verb-movement can be set by the language learner on the basis of inflectional information. However, the inflection is not the only positive evidence that the language learner gets in order to set the parameter. Word-order patterns in the input (i.e., the sequence verb–adverb or adverb–verb) also provide robust positive evidence allowing the learner to determine the parameter-setting. Thus, two types of evidence are available to the language learner for fixing the parameter: syntactic evidence (wordorder) and morphological evidence (inflection).

5.1 Morphology And The Setting Of Parameters

Both parameters of cross-linguistic variation discussed so far are related to inflection. The question arises whether all parameters can be stated in terms of inflectional variation. One area of cross-linguistic variation whose definition remains subject to controversy concerns the contrast between so-called VO languages such as English, in which the verb precedes its direct object, and OV languages such as Dutch and German, in which the direct object precedes the verb:

(15a) I think that John knows this house.

(15b) Ik denk dat Jan dit huis kent. (Dutch)

*I think that Jan this house knows.

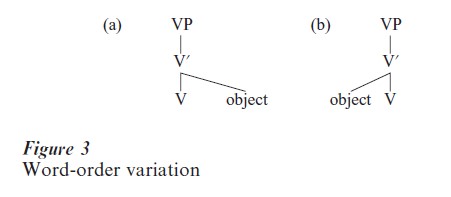

According to the more traditional approach, the variation in (15) is due to a parametric variation in the underlying structure of these languages. In this view, the universal principles of structure (Fig 1) only determine hierarchical relations, leaving the linear order of the constituents to be determined parametrically. Thus the structure of the VP would come out as Fig. 3a for English and as Fig. 3b for Dutch.

The universal base approach, on the other hand, assumes that structure determines linearization and that the verb always precedes the object; (Fig. 3b) is not a possible base structure. In this view, the OV order of Dutch (15b) is derived by a leftward movement of the object. Those adopting the universal base approach define the trigger of the leftward movement of the object in Dutch (15b) in terms of a morphological property of the object. Since the Dutch object does not, at first sight, display any visible properties to distinguish it from its English counterpart, it is proposed that morphological variation need not correspond to an overt manifestation; morphological properties at the basis of cross-linguistic variation may also be abstract.

5.2 Diachronic Change And The Trigger For Parameter (Re-)Setting

Two types of overt evidence in the input allow the learner to formulate his her grammar: syntactic evidence (the observed word-order sequence verb– adverb–direct object vs. adverb–verb–direct object, the observed omission of the subject) and morphological evidence (the verbal inflection). The question arises whether either of these two kinds of evidence is primary in parameter setting.

Inflectional endings in a language get weakened and disappear in the course of time. As a result, the morphological evidence for a given parameter-setting disappears. The development of English suggests that the loss of inflectional morphology led to the loss of leftward verb movement (cf. Roberts 1993, Pollock 1989). Changes in the inflection have led to a re-setting of a parameter. Apparently, when the morphological evidence gets lost the syntactic evidence alone is insufficient for triggering the relevant parameter-setting (see Vikner 1997, pp. 205ff. on Scandinavian). The loss of the morphological trigger for a particular word-order does not necessarily lead to an abrupt change in the word-order patterns of the language. A syntactic trigger (i.e., the word-order pattern itself) can maintain the old system for some time, leading to gradual, rather than abrupt change.

Bibliography:

- Chomsky N 1981a Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

- Chomsky N 1981b Principles and parameters in syntactic theory. In: Hornstein N, Lightfoot D (eds.) Explanations in Linguistics. Longman, London, pp. 123–46

- Chomsky N 1986 Knowledge of Language. Praeger, New York

- Emonds J 1980 Word-order in generative grammar. Journal of Linguistic Research 1: 33–54

- Haegeman L (ed.) 1997 The New Comparative Syntax. Addison, Wesley, Longman, London

- Holmberg A, Platzack C 1995 The Role of Inflection in Scandinavian Syntax. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Jaeggli O, Safir S 1986 The Null Subject Parameter. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

- Lightfoot D 1991 How to Set Parameters. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Perlmutter P 1971 Deep and Surface Structure Constraints in Syntax. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

- Pollock J-Y 1989 Verb movement, universal grammar and the structure of IP. LI 20: 365–424

- Rizzi L 1986 Null objects in Italian and the theory of pro. LI 17: 501–57

- Roberts I 1993 Verbs in Diachronic Syntax. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

- Ross, J R 1967 Constraints on variables in syntax. Ph.D. thesis, MIT

- Vikner S 1997 V-to-I movement and inflection for person in all tenses. In: Haegeman L (ed.) The New Comparati e Syntax. Addison, Wesley, Longman, London, pp. 189–213

- White L 1989 Universal Grammar and Second Language Acquisition. John Benjamins, Amsterdam