Sample Morphological Case In Linguistics Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Case, as traditionally understood, refers to a system of inflection, usually in the form of suffixes, that marks the relation of nouns in a clause. In the Latin sentence Calpurnia Clodiam vıdit ‘Calpurnia saw Clodia’ the fact that Clodia rather than Calpurnia is the one who is seen is signalled by the -m suffix on Clodia, rather than by word order as in English. This -m is a case suffix.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Case, Case Form, And Case Marker

A morphological case system is a system of inflection that marks dependents for the type of relation they bear to their heads. Typically, case marks the relationship of a noun to a verb at the clause level or of a noun to a preposition, postposition, or another noun at the phrase level. Consider the following Turkish sentence:

(1) Ali adam-a elma-lar-ı ver-di

Ali.NOM man-DAT apple-PL–ACC give-PAST.3SG

‘Ali gave the apples to the man.’

The suffix -ı indicates that elmalar is the direct object of the verb vermek ‘to give’ and the suffix -a indicates that Adam is the indirect object. The suffix -ı is said to be an accusative (or objective) case marker and the word form elmaları is said to be in the accusative case. The suffix -ı also indicates that elmalar is specific, since in Turkish only specific direct objects are marked as accusative. The suffix -a is a dative case marker. Ali contrasts with elmaları and adama in that it bears no overt suffix. It is said to be in the nominative case, which is this sentence indicates the subject.

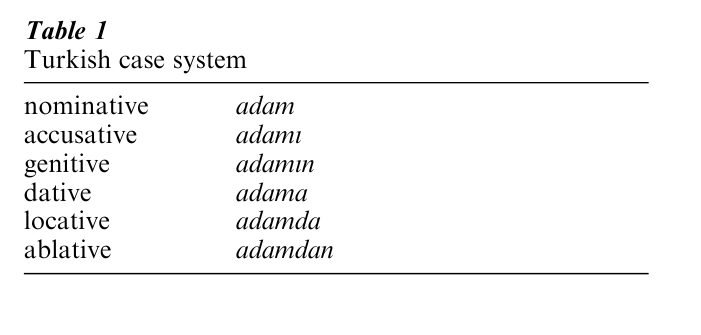

Turkish has a system of six cases as in Table 1. The locative marks location as in Istanbul-da ‘in Istanbul,’ and the ablative indicates ‘from’ or ‘out of’ as in Ankara-dan ‘from Ankara.’ The genitive is used in phrases like adam-ın ev -i ‘the man’s house’ where ın corresponds to ’s in English. The suffix -i on e ‘house’ is a third person possessive form translatable as ‘his,’ ‘her,’ or ‘its’. In Turkish ‘the man’s house’ is literally ‘the man’s, his house’.

The word forms displayed in Table 1 make up a paradigm, that is, they constitute the set of case forms in which the lexeme adam can appear. In Turkish one could say that there is only one paradigm in that a single set of endings is found for all nouns, although these suffixes do undergo some phonologically conditioned changes such as undergoing vowel harmony and the like. The locative, for instance, has the form-da following stems with back vowels and -de following stems with front vowels. A distinction needs to be

made between cases (of which there are six in a system of oppositions), and the case markers or case forms through which the cases are realised. A case marker is an affix and a case form is a complete word. In Turkish the case affixes can be separated from the stem, so it is possible to talk about case markers. In some languages, however, it is not possible to isolate a case suffix, so it is necessary to talk in terms of the various word forms that express the cases of the stem. These are case forms.

2. Case Marking Fused With Number And Gender

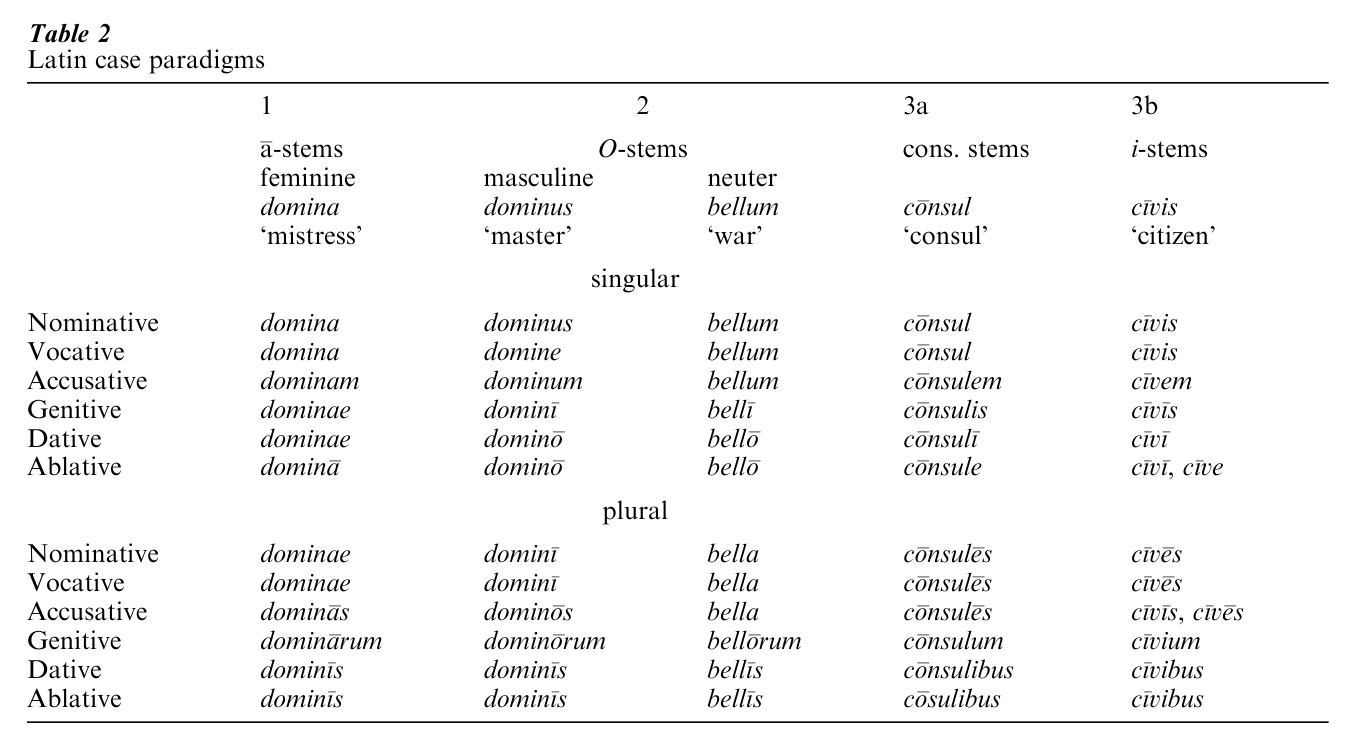

The traditional notion of cases and the associated terminology were developed on the basis of Ancient Greek and Latin where it is not possible to separate number marking from case marking. This means separate paradigms for the two number categories, singular and plural. Moreover, there are different case/number markers for different stem classes. In Latin five such classes are recognised, or five declensions as they are called. The three major declensions are illustrated in Table 2.

In Latin there is also a three-way gender distinction: masculine, feminine, and neuter. With a few exceptions male creatures are masculine and females feminine, but inanimates are scattered over all three genders (though almost all neuter nouns are inanimate). There is a partial association of form and gender in that astems are almost all feminine and o-stems mostly masculine (except for a subclass of neuters represented by bellum in Table 2). This means that there can be fusion of gender, number, and case. The point is illustrated in Table 2 where we have domina ‘mistress (of a household)’ illustrating feminine a-stems and dominus ‘master (of a household),’ which is based on the same root, representing masculine o-stems. As can be seen from Table 2 the word form domina simultaneously represents nominative case, feminine gender, and singular number, dominum represents accusative case, masculine gender, and singular number, and similarly with other word forms.

Where there is more than one paradigm, it frequently happens that distinctions made in one paradigm are syncretized or neutralized in others. In the traditional descriptions a case is established wherever there is a distinction for any single class of nominals. Informally one might consider that a case is a row in a set of paradigms like those in Table 2. Dealing in cases (‘rows’) facilitates the description of the relation of form and function. A particular case can be said to have one or more functions without reference to the details of the forms.

The functions of the cases in Latin, and in Ancient Greek, are important in that they have served as a model for applying case labels in other languages such as Turkish. In Latin the nominative encodes the subject and the accusative the direct object. The dative marks the indirect object of a few three-place verbs such as dare ‘to give’ and the complement of a few two-place verbs including credere ‘to believe,’ nocere ‘to be harmful to,’ and sub enıre ‘to help.’ The genitive is used mainly to mark noun phrases as dependents of nouns, in particular to mark the possessor: consulis equus ‘the consul’s horse.’

The ablative in Latin represents the syncretism or merger of three once-distinct cases: the ablative, the locative, and the instrumental so it is not surprising then to find that it expresses source, location, and instrument.

The vocative is anomalous in that it does not mark the relationship of dependents, but is used as a form of address as in Quo vadis, domine? (whither go.2SG lord. VOC) ‘Where are you going, master?’ However, the vocative belongs with the other cases since its marking belongs to the same system as the unequivocal cases.

Latin uses a system of prepositions in addition to the case system. Some prepositions, including all those expressing destination, such as ad ‘to’ govern the accusative (ad urbem ‘to the city’), while others such as ex ‘out of, from’ govern the ablative (ex urbe ‘from the city’).

3. The Range Of Case Systems

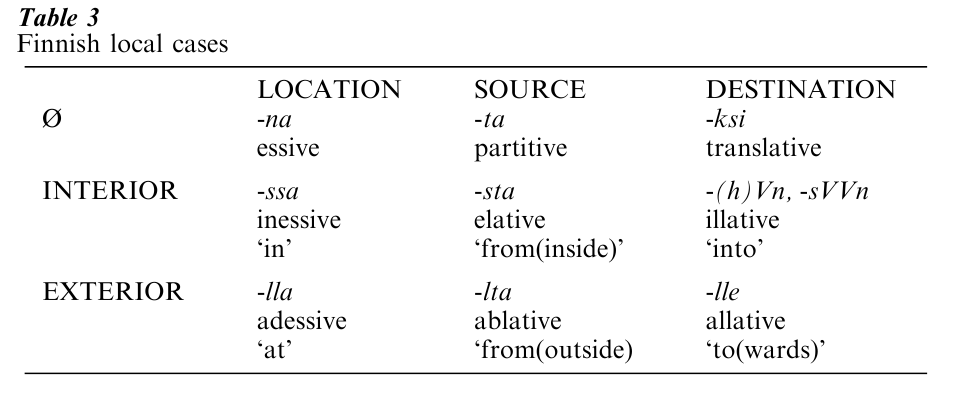

Case systems differ in terms of the number of distinctions they make and range from a minimum of two as in some Iranian languages, which have a nominative and an oblique, to figures like 15 in Finnish (see Table 3).

Case systems also vary in terms of the type of distinction they make in a given domain. While many languages are like Latin in having one case for the subject, namely the nominative, and another case for the direct object (the accusative), some languages including Basque, northeast Caucasian languages, and many Australian languages have one case for the subject of a transitive verb, which is called the ergative, and another case to cover the subject of an intransitive predicate and the direct object. This case is generally morphologically unmarked, that is, there is no form. Some writers call this case the absolutive; others call it the nominative. The following illustration is from the Australian language Kalkatungu where the ergative is realised by the suffix -yu and the absolutive/nominative is unmarked. Note, however, that with the crossreferencing clitics that are attached to the purposive auxiliary a common from represents the subject and a distinct form the object.

(2) Nhutu a=nhurr ingka?

You.NOM PURP = 2PL.SUBJ go

‘Are you mob going?’

(3) Nhutu-yu a=nhurr nuwa puyu?

you-ERG PURP = 2PL.SUBJ see 2DU.NOM

‘Are you mob going to see them two?’

(4) Nhutu a=kutu nuwa puyu-yu

you.NOM PURP = 2PL.OBJ see 2DU–ERG

‘They two want to see you mob.’

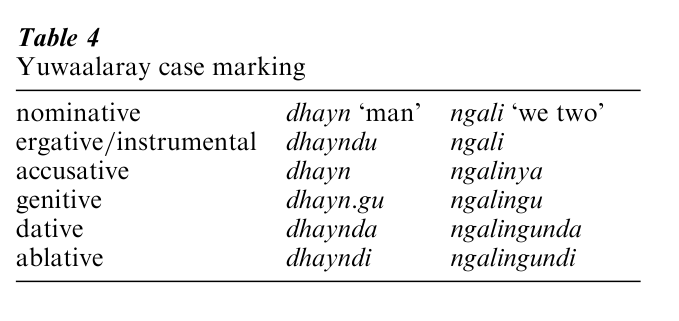

In a number of languages, particularly in Australia, accusative and ergative marking are found in the same language. As pointed out by Silverstein (1976), there tends to be some complementarity with ergative marking confined to nouns and accusative to pronouns or to pronouns plus certain classes of noun such as kinship nouns, personal names or in some instances all human nouns. The following paradigms from another Australian language, Yuwaalaray, show ergative marking with nouns and accusative with pronouns (see Table 4).

Every language has to provide for the expression of a large number of local notions. This can be done via adpositions as with English prepositions such as on, to, o er, and under. Where a number of local notions are expressed via the case system the number of cases naturally rises. In Finnish, for instance, the notions of location, source, and destination can combine with the notions of interior and exterior to produce a set of nine local cases as illustrated in Table 3. Originally there were two systems (location, destination, and source) and (interior, exterior, and neither), but the markers have partially fused. The functions are no longer entirely local either. The partitive is used for the patient if it represents part of a whole or an indefinite quantity, or if the action is incomplete, or if the polarity of the clause is negative. The translative refers to the endpoint of a transformation as in She turned the frog into a prince.

Other cases commonly encountered include the comitative, expressing accompaniment (I went with them) and instrumental expressing the instrument used to carry out an action (She wiped the screen with a cloth).

In the Uralic language a case called abessive is found. It means ‘without’, ‘not having.’ In Finnish, for instance, rahta-tta is (money-AB) ‘moneyless.’ This case is also found in Australia where it is matched by a ‘having’ case sometimes called the proprietive.

4. Classifying Cases

The Greeks made a primary distinction between the nominative and the other cases, collectively called the oblique cases. This makes sense when one considers the nominative was the form used in isolation whereas the other forms generally required a particular syntactic context. In some languages there is a formal distinction between the nominative and the oblique cases inasmuch as there is a special stem for the obliques. This is the situation in many Dravidian and northeast Caucasian languages, for instance. In most languages the nominative bears no marking as in Turkish (Table 1), but consists of the bare stem. Indo–European case languages are unusual in having a marked nominative in most paradigms (Table 2).

Another distinction that is often made is between grammatical (or syntactic) cases and semantic (or concrete) cases. The grammatical cases are traditionally taken to include the nominative and accusative and often the genitive, and should include the dative and the ergative. The basis for the distinction is often not made clear, but if the criterion for classifying a case as grammatical or syntactic is that it expresses a purely syntactic as opposed to semantic relation, then the dative and ergative should certainly be included since the dative encodes the indirect object and the ergative encodes the ‘transitive subject.’

If the distinction between grammatical and semantic cases were to be clearcut, the grammatical cases would encode only purely syntactic relations and the semantic cases would encode only homogeneous semantic relations such as location or source. However, it is common for a syntactic case to encode a semantic relation or role that lies outside of whatever syntactic relation it expresses. In Latin, for instance, the accusative not only expresses the direct object, it also expresses the semantic role of destination as in Vado Romam ‘I am going to Rome.’ On the other hand, there are situations where the so-called semantic cases encode a purely syntactic relation. This commonly occurs with the passive where the demoted subject is often expressed via a semantic case. In Latin the demoted subject is encoded in the ablative as in vısus a consule ‘seen by the consul.’

It is also convenient for the purposes of making certain generalisations to distinguish the cases that encode the complements (including the subject) of typical one-place and two-place transitive verbs. These are the nominative, ergative and accusative, and they are known collectively as the core cases and the others as peripheral cases. There is another set of terms in use, namely direct and oblique. These terms are used in the description of Indo–Aryan languages where the direct case covers subjects and objects.

In some treatments the term local cases is used to cover cases designating notions of place such as location, source, destination or path (Table 3).

5. Exponence

The relation between the verb and its dependents, whether complements or adjuncts, may be expressed by an adposition, either a preposition as in English or a postposition as in Turkish. In languages with morphological case systems there are usually adpositions as well as cases. In Latin, as we have seen, there are prepositions, and in Turkish there are postpositions such as sonra ‘after,’ which governs the ablative: tiyatro-dan sonra (theatre-ABL from) ‘after the theatre.’ In such languages there are essentially two systems: an inner, restricted system of case and an outer, more elaborate system of adpositions. In some languages such as Japanese there is just one system of postpositions, which includes markers for subject, direct object, indirect object, and topic, as well as for local notions such as ‘from.’ In such a language the distinction between case and adposition is essentially neutralized. In the following Japanese example ga marks the subject, ni marks the indirect object, and o marks the direct object.

(5) Sensei ga Tasaku ni hon o yat-ta

teacher SUBJ Tasaku IO book DO give-PAST

‘The teacher gave Tasaku a book.’

Morphological case is almost always realised as a set of suffixes, though there are instances where there is some mutation of the stem or complete suppletion as with the English pronouns: I/me, she/her, we/us, and also he/him and they/’em/them where the -m is an old dative suffix.

Where categories such as number, gender or possessor are marked as well as case and where these categories are not fused, case marking normally follows these other categories as in Turkish : adam-larım-la (man-PL-1SG.POSS–LOC) ‘with my men’ where the number marking and possessor precede the case marking.

Within the noun phrase there are two common distributions for case marking. Either it occurs on all types of nominal or it is occurs on only one word.

In the former type the distribution is traditionally described in terms of dependents showing case concord or agreement with a noun head. In the following example from Ancient Greek bıos is a nominative singular form of a second declension (o-stem) masculine noun, the nominative indicating that bıos is the subject of the predicate. The definite article and the adjective are in the nominative singular masculine form, their concord in case, number and gender indicating that they are dependents of bıos,

(6) Ho aneksetastos bıos

the.NOM.SG unexamined.NOM.SG life.NOM.SG

ou biotos anthropoi

not livable. NOM.SG man.DAT.SG

‘The unexamined life is not livable for man.’

This example also illustrates concord between a predicative adjective (bıotos) and the subject (bıos). While concord of case, number, and gender of predicative adjectives is the norm in Latin and Ancient Greek, in many other languages predicative adjectives display no concord. This is the situation in German where the predicative adjective consists of the bare stem and is distinct from the various case forms.

Case concord within the noun phrase is found in the older Indo–European languages and also in Balto–Finnic, Semitic, in some Australian languages, and elsewhere, but it is a minority system. In some languages such as Hungarian the concord does not extend to the adjective and in the Indo-Aryan languages adjectives exhibit fewer case distinctions than nouns. In the more conservative Germanic languages, including modern German, the adjective shows fewer case marking distinctions where a determiner is pre- sent.

In most languages case concord does not extend to dependents in the genitive case. However, in Georgian a postposed genitive exhibits concord, which results in double case marking: compare davit-is mama-s (David-GEN father-DAT) and mama-s davit-isa-s (fatherDATDavid-GEN–DAT ‘to David’s father’).

Where case marking occurs on only one word in the noun phrase, it is usually on the final word. In many languages, including a vast number in northern Asia and South Asia, the final word is the head noun in the noun phrase. The following example is from the Dravidian language Kannada:

(7) Naanu ellaa maanava janaangavannu

I.NOM all human community.ACC

priitisutteene

love.1SG

‘I love all mankind.’

In some languages the final word in the noun phrase is not always the head. This is the situation in various Australian and Amazonian languages, and in Basque: etxe zaharr-etan (house old-PL.LOC) ‘in old houses.’

6. History

Since bound forms in general derive from free forms, it is not surprising that there is evidence of case markers deriving from nouns and verbs, often via postpositions. For instance, the Hungarian illative (‘into’) case marker -ba as in vilag-ba ‘into the world’ derives from a noun bel ‘innards’ and the allative case marker-tharri in the Australian language Kunggari derives from a verb tharri ‘to become.’

Case marking may also be lost. This is quite striking in Europe, particularly among the Romance languages. The Latin system of noun inflection illustrated in Table 2 has been lost from the Romance languages except for a reduced system retained in Rumanian. The Germanic languages too have lost case distinctions over the last 2 millennia with English and Afrikaans having lost all case marking on nouns, though German still retains a four-case system: nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative. In languages like English and the Romance languages case distinctions have been retained on pronouns. Case marking can fall prey to phonetic attrition and the availability of prepositions and word order as alternative means of making the relevant distinctions must also be a factor in the loss of case.

Bibliography:

- Blake B J 1994 Case. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U K

- Brecht R D, Levine J S (eds.) 1986 Case in Slavic. Slavica Publishers, Columbus, OH

- Comrie B 1986 On delimiting cases. In: Brecht R D, Levine J S (eds.) Case in Slavic. Slavica Publishers, Columbus, OH, pp. 86–105

- Mel’cuk I A 1986 Toward a definition of case. In: Brecht R D, Levine J S (eds.) Case in Slavic. Slavica Publishers, Columbus, OH, pp. 35–85

- Silverstein M 1976 Hierarchy of features and ergativity. In: Dixon R M W (ed.) Grammatical Categories in Australian Languages. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, Humanities Press, New Jersey, pp. 112–71