Sample Language And Poetic Structure Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Language is the material out of which poetry is made. Language itself is, of course, a complex phenomenon, involving both a characteristic structure, consisting of a grammar and a lexicon, and characteristic uses, such as communication and expression. All of these elements play a role in poetic structure. This research paper, however, will focus mainly on grammar, and its relationship to such characteristic aspects of poetic structure as meter, rhyme and alliteration, and syntactic parallelism. These define the core forms of versification found across the world’s languages, and create poetic effects even when they are not used regularly enough to constitute versification. In recent decades, they have been the subject of striking new directions of research, as a result of new directions of research in grammar.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Grammar And Verse

Versification by definition imposes formal constraints on language beyond those to which it conforms intrinsically. To describe those constraints for any given verse form is a surprisingly challenging intellectual problem, because individual lines within a form are all different from one another, often artfully so for expressive purposes. It is thus a problem, as Jakobson (1981a) influentially put it, of abstracting the invariant ‘verse design’ away from the variation embodied in all the ‘verse instances.’ Even for those verse forms, especially in written traditions, for which some constraints have been articulated, the problem remains a challenging one, in that poets’ actual practice may not necessarily match the articulated constraints: some lines which appear to violate them may nonetheless be included in compositions in the form, at the same time that some which appear to conform to them may nonetheless never be used. Such mismatches suggest that the articulated constraints may not constitute a complete and true description of what a poet instinctively knows about a form.

Construing the problem of describing a verse form as making explicit the unconscious as well as conscious knowledge a poet has of what defines the form makes it, as Halle and Keyser (1972) point out, analogous to the problem of describing grammar itself. In Chomsky’s (1965) influential formulation, grammar is the knowledge a fluent speaker of a language has, partly consciously and partly unconsciously, of what would or would not be well-formed instances of the language. In phonology, for example, the subsystem of grammar dealing with sound structure, an English speaker knows not only that the combination of sounds in ‘brick’ is an actual word and that in ‘blick’ is not, but also that ‘blick’ is a possible word, whereas ‘*bnick’ is not only not an actual word but also not a possible word; the ‘*’ indicates its illformedness. Similarly in syntax, an English speaker knows that a sentence like ‘The cat stretched sleepily’ is a possible sentence of English while ‘*Sleepily cat stretched the’ is not. To describe the grammar of a language is to make the constraints which constitute such knowledge fully explicit. The research program within linguistics which adopts that goal is ‘generative linguistics,’ and its analog for verse is sometimes termed ‘generative poetics.’

Describing a verse form involves grammar in substantive aspects as well. Although meter, rhyme and alliteration, and syntactic parallelism are often de- scribed metaphorically as contributing music to poetry, the entities which define them—particular configurations of syllables and stress, vowels and consonants, noun phrases and verb phrases—are, of course, quite specific to grammar. This means that as research into grammar has sought to discover the fundamental entities and/organizational principles of grammars, new formal structures have become available to serve in descriptions of verse forms, sometimes leading to striking new insights into familiar forms. By the same token, research into verse forms has some- times suggested or supported hypothesized entities or principles of grammar.

In this regard, two ideas which have shaped grammatical research have been particularly significant for research into versification. One is the assumption, going back to de Saussure (1983) and carried on in generative grammar, that grammar is at some level purely formal: phonology is not reducible to sound, and syntax is not reducible to meaning. The entities of grammar defining verse forms may thus sometimes prove to be surprisingly abstract.

The other is the conceptualization of the grammar of any particular language as one instance of a common phenomenon of human language. Although this idea also has a long history, including notably for poetics the interest in it taken by Jakobson and his circle, it was given a particularly galvanizing formulation in Chomsky’s (1965) suggestion that the most basic formal properties of grammars might be essentially similar across all languages because they are innately determined. This hypothesis of ‘universal grammar’ motivates the relevance of wide-ranging cross-linguistic phenomena to the formalization of any single language’s grammar. For versification, this means that evidence for particular ways of analyzing the structures figuring in a verse form may come from languages unrelated to that of the verse in question.

The observation that the goals and vocabulary of the description of verse are similar to those of the description of grammar invites the deeper question of whether there can be a theory of versification, as there are theories of grammar, and, if so, what specific relationship of versification to grammar such a theory might posit. After all, there are differences as well as similarities: we can usually tell in an instant whether language is verse or not. Again it was Jakobson (1962–81a) who influentially suggested that it is specifically the sequencing of entities which are in some way equivalent in the language which constitutes poetic effects. Interpreting this in light of the formal and universalist understanding of grammar characteristic of generative theories, Kiparsky (1981b, 1987) ventured one of the first testable theories of versification, hypothesizing that verse forms might be constituted by repetition of exactly those phonological and syntactic structures to which the constraints which constitute grammars universally make reference.

One of the simplest observations in support of this idea is that each of the major forms of versification corresponds to a major subsystem of grammar. Let us turn then to some specific recent examples of descriptive and theoretical claims following this line of inquiry, and then consider some of its consequences and limitations.

2. Meter

The phonology of every language involves two distinct though interrelated subsystems, one dealing with rhythm, such as the quantitative grouping of sounds into stressed and unstressed syllables, and the other dealing with what is technically termed ‘melody,’ referring not only to tones, but also to the qualitative characteristics of segments, such as what makes a ‘p’ different from a ‘b.’ Verse forms which impose constraints on rhythmic structure beyond those given by the phonology are meters.

The dominant meter of the modern English poetic tradition, the iambic pentameter, affords a well-developed example of how changes in the goals and substance of grammatical description have wrought changes in the conceptualization of a familiar verse form. Traditionally, the iambic pentameter has been described as having a basic form of five feet, each consisting of an unstressed syllable (x) followed by a stressed one (/ ):

(a) x/ x/ x/ x/ x/

While many lines, such as (bi), have exactly that rhythmic structure, many others, such as (b) (ii)–(iii), do not:

(b) (i) So long as men can breathe and eyes can see (Shakespeare, Sonnets 18, 13)

(ii) Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger’s jaws, (19, 3)

(iii) For how do I hold thee but by thy granting, (87, 5)

Such variations have traditionally been attributed to the possibility of substituting different kinds of feet with different patterns of syllables and stress, such as trochees (/x), spondees ( // ), phyrrics (xx), or anapests (xx/ ), so long as any sense of the basic form doesn’t get lost. But as Halle and Keyser (1972), building on Jespersen (1933), point out, unless it makes explicit under what conditions the basic form would indeed get lost, such a description fails to capture what the poet knows that leads to acceptance of some variations as metrical, but avoidance of other imaginable ones as unmetrical. The construct in (c), for example, sounds like prose, not verse, and in fact has a rhythmic structure not found in any lines in Shakespeare’s sonnets:

(c) *Imaginable lines are avoided.

Yet it can be analyzed into basic and substituted feet just as the lines in (b) (ii)–(iii) can; nothing in that description of the iambic pentameter captures its fundamental difference of unmetricality.

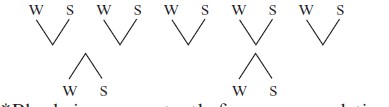

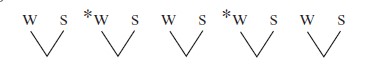

Much research has gone into the question of how the iambic pentameter can be modeled so as to in fact represent this knowledge. Most fundamentally, Halle and Keyser (1972) suggest that the meter needs to be distinguished from the actual rhythmic structure of the line, and formalized in two components: an abstract rhythmic template, composed of weak (W) and strong (S) metrical positions, and simple constraints on how certain aspects of the rhythmic structure of the line can be mapped into the template.

Observing that lines such as those in (d), which are rhythmically similar to those of (b) (ii)–(iii) but have polysyllabic words where (b) (ii)–(iii) have mono-syllables, do not appear in Shakespeare’s sonnets, Kiparsky (1977) proposes specifically the template and constraints in (e), informally restated:

(d) (i) *Pluck immense teeth from enraged tigers’ jaws

(ii) *For how do I prosper but by the granting

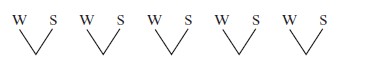

(e) (i) ws ws ws wsws

(ii) Each metrical position corresponds to a syllable.

No weak metrical position corresponds to a syllable which is strong relative to another syllable in the same word.

This proposal is shaped in substantive ways by a model of linguistic rhythm itself as essentially relative, with elements at successive levels grouped into constituents in which one element is strong and any others weak (Liberman and Prince 1977), such that a polysyllabic word involves a relationship of relative strength between syllables that a monosyllabic word does not. Thus, lines like (b) (ii) can be mapped into the template in (e) (i) in accordance with the constraints in

(e) (ii), while (d) (i), let alone (c), cannot:

s w

(f ) (i) Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger’s jaws,

(ii) *Pluck immense teeth from enraged tiger’s jaws

The cross-linguistic study of rhythmic systems within Liberman and Prince’s model has led to the discovery of a rich range of abstract structures, with surprising consequences for the description of many other aspects of metrical structure as well. For example, the familiar possibility of ‘feminine endings,’ the inclusion of an extra unstressed syllable at the end of a line as in (b) (iii), proves to have an analog in the grammar of rhythm, in that in many languages final syllables are regularly ‘extrametrical,’ or outside the basic groupings which define stress patterns (Hayes 1995). And the possibility in some iambic meter of ‘trisyllabic substitution,’ or inclusion of extra unstressed syllables within a line as in (g), has been attributed to the role of a particular linguistic grouping of syllables called a ‘phonological foot,’ which in many languages takes the form of either a single stressed syllable, like ‘sea’ or ‘-ract,’ or two syllables of which the first is stressed and light, like ‘cata-’ (Hayes 1995, Hanson and Kiparsky 1996).

(g) In cataract after cataract to the sea (Tennyson,‘OEnone,’ 9)

This possibility has in turn illuminated the structure of other English meters which were previously obscure, such as Hopkins’ ‘Sprung Rhythm’ (Kiparsky 1989), as well as meters of entirely unrelated traditions, such as Finnish. In fact, the universal theory of grammatical rhythm is so well-developed at this point that it has been possible to propose a universal theory of meter based on it (Hanson and Kiparsky 1996), though its cross-linguistic explanatory value remains largely still to be explored.

A template and constraints as in (e) are, of course, only the most basic elements of a metrical description. Even for English iambic pentameter, there are systematic exceptions to the constraints of (eii), as well as additional strictures that they do not capture, and the details are different for every poet and genre; as Kiparsky (1977) observes, describing an individual poet’s practice within a metrical tradition is analogous to describing dialects within a language. While formalizing these complexities has likewise made progress by drawing on insights into grammatical structure, many open questions remain. For example, knowledge of a meter clearly includes recognition not only of the limits of well-formedness, but also of specific effects of metrical complexity and simplicity that can be created within those limits. How is that knowledge expressed in models like that in (e)? Is even knowledge of well- formedness best modeled through identification of a limit, or of gradient distance from a prototype (Youmans 1989)? Interestingly, while such questions pose challenges for metrical description, they do not necessarily challenge the theoretical assumption of the close relationship of meter to grammatical rhythm; rather, parallel questions have been posed about modelling grammar itself.

3. Alliteration And Rhyme

The family of poetic effects which includes alliteration and rhyme is often referred to as ‘sound patterning.’ The term is somewhat unsatisfactory, however, since it is not clear why these forms have any better claim to be described as ‘sound’ than meter does, at the same time that sound is not really what any such forms involve, so much as phonological structure. Since the structure they involve is specifically melodic, a more appropriate collective term for them might be ‘poetic melody,’ parallel to ‘poetic meter.’

Again it was Jakobson (1963) who, in an influential analysis of Germanic alliteration, showed how explicit characterization of such forms as repetitions can lead to discoveries about their relationships to grammar. In Old English verse, for example, syllables in certain positions must alliterate, meaning they begin either with the same consonants, as in (h) (i); or with any vowels, as in (h) (ii):

(h) i. Da middangeard moncynnes Weard

‘then middle earth mankind’s Guardian’

- ece Drihten æfter teode

‘eternal Lord afterwards made’

Jakobson observes that no characterization of alliteration in terms of identities of sounds can generalize across this differential treatment of consonants and vowels, and instead relates it to syllable structure. Segments which precede the most sonorous element in each syllable, typically though not always the vowel, constitute an ‘onset’: in ‘rate,’ for example, it would be the [r], or in ‘trait’ the [tr]. Modifying Jakobson’s own analysis somewhat, Kiparsky (1970, 1981) points out that if , in ‘ate’ there is simply no onset, or an empty one, then alliteration can be characterized simply as requiring structural identity of corresponding syllables up through the first segment in the onset. Moreover, onset structure explains another peculiarity of Germanic alliteration, in that exceptionally for the clusters [sp, st, sk], the second segments must also be the same. As Jakobson noted, there is evidence that the [s] in these configurations is outside the core onset structure, or ‘extrasyllabic’ (compare the fact that in modern English, onsets normally contain no more than two segments, but initial [s] in an onset like that of ‘straight’ is excepted); thus, the second segment in the cluster really is the first in the onset, and its required identity follows. This explicit account of the locus of Germanic alliteration stands as a model for the analysis of other melodic forms: while rhyme, for example, in all its various forms like full rhyme, slant rhyme or assonance are all assumed to be formalizable, and in ways that similarily draw on grammatical structure, the details of poets’ actual practice have seldom been fully worked out in conjunction with explict theories of syllable structure.

Another way in which poetic melody draws on grammatical structure involves the explicit characterization of ways in which sounds can be similar.

In language, segments are often pronounced systematically differently depending on their phonological context. Modelling such knowledge has typically relied on two key assumptions. First, segments are not monolithic, but composed of distinctive features. Second, individual lexical items have an ‘underlying structure’ which may be distinct from their ‘surface structure’ which determines pronounciation, because phonological processes may alter some features in some contexts (Chomsky and Halle 1968). Poetic melody exploits this kind of knowledge in a variety of ways. First, as Zwicky (1976) suggests for the rhymes of English rock lyrics, a form may simply require corresponding sounds to differ by no more than one feature: in made and babe, for example, [d] and [b] differ only in their place of articulation feature, and in made and late, [d] and [t] differ only in their feature of voicing, or vibration of the vocal cords. Second, Kiparsky (1970) suggests that poets’ practice is sometimes based on underlying rather than surface forms. For example, Malone (1987) notes that Irish has a grammatical process which nasalizes voiced stops ([b, d, g]) in certain contexts, which explains why poets allow a word like bo ‘cow’ to alliterate with mban ‘white (gen.pl.)’: the initial sound of the latter is underlyingly [b], though the nasalization process makes it different on the surface Third, poetic forms sometimes require identity of some features but not others, a phenomenon also found in Irish. Irish rhymes require that segments in corresponding positions belong to the same class of consonants; for example, one such class is the voiced stops [b,d,g], such that ec ‘death’ (in which the ‘c’ spells [g]) can rhyme with bet ‘misdeed’ (in which the ‘t’ spells [d]). That this class is targeted by the nasalization process which gives mban makes it a particularly clear instance of what Kiparsky hypothesized to be the general case in verse forms, of the equivalences that define them being the same equivalences which figure in grammar.

Collectively, the foregoing ideas and the cross- linguistic studies which support them suggest that melodic forms support a good deal of variety across verse instances in the same way that metrical forms do, but formalizing their verse designs has generally received less attention. In English, for example, Zwicky’s (1976) study has inspired many interesting observations of variation in the high art rhyme tradition as well, but few studies have worked out explicit models of the possible complexities and their limits in the practice of individual poets, let alone characterized them as variations on an overall tradition. A particularly interesting theoretical impetus to such studies has recently come, however, from cross- linguistic studies of reduplication, systematic processes in which all or part of the beginnings or ends of words are copied to derive new words or forms of words, as illustrated in (i):

(i) i. Gothic past tense: haitan ‘call’ hai-hait ‘called’

slepan ‘sleep’ sai-slep ‘slept’

- Chamorro inten dankolo ‘big’ dankolo-lo

sives: ‘really big’

bunita ‘pretty’ bunita-ta ‘very pretty’

As Kiparsky (1973) points out, melodic verse forms often involve the same kinds of grammatical analyses that reduplication does; thus, as the intricate variety of reduplication systems has begun to be studied, universal theories of poetic melody analogous to those advanced for meter have begun to be possible for the first time (Holtman 1994, Yip 1999).

4. Syntactic Parallelism

Finally, in many languages it is not phonology, or at least not phonology alone, which defines verse forms, but morphology and syntax, through requirements of parallel structures from line to line. One of the most influential traditions of this kind is that of ancient Hebrew poetry, exemplified by the passage in (j), together with a translation of it by Jakobson (1981b):

(j) ittı mill banon kallah

with me from Lebanon bride

ittı mill banon tabo ı

with me from Lebanon come!

tasurı mero s amanah

depart from the peak of Amanah,

meros snır whermon

from the peak of Senir and Hermon,

mimm onot arayot

from the lairs of lions

mehar rey n merım

from the mountains of leopards!

(‘Song of Solo mon’ 4:8)

Here again, making explicit what the evident repetition consists of raises interesting grammatical questions. The fifth and sixth lines transparently have a common morphological and syntactic structure: the individual words differ, but the grammatical classes of their component parts and resulting wholes are identical: prepositions, plural nouns, etc. But the structures of the third and fourth lines appear to differ in that there is a verb, tasurı ‘depart’ in the third which is absent from the fourth, and a conjoined noun in the fourth, w hermon ‘and Hermon,’ which is absent from the third. From the point of view of syntax, however, a noun phrase consisting of a single noun can be identical to one consisting of conjoined nouns: in English, for example, a preposition which requires a noun phrase object will be indifferent to the internal structure of the noun phrase, so that [[from]P [Mary]NP]] and [[from]P [[Mary]NP and [John]NP ]NP] are structurally identical at the level of their [P NP] structure. Similarly, in certain constructions involving parallelism in language itself, a verb which is absent in the surface structure may be understood to be present underlyingly, under identity with a verb in a conjoined clause: in [[Mary [ate]V fish]S and [John [ ]V meat]s], the syntactic well-formedness of the second clause requires the assumption that the unpronounced verb is present at some level of analysis. Even in the first two lines, as Jakobson (1966) points out, the vocative kallah ‘bride’ and the imperative tabo/i ‘come’ share a function of direct address, which may entail further syntactic similarities. Thus, even parallelism which appears to be principally semantic may involve identical syntax at an abstract level. The forms of syntactic parallelism across languages—Finnish, Chinese, Galician, for example—are as diverse as the languages themselves, but all merit further study from a syntactic point of view.

5. Conclusion

Versification represents, of course, only one of many ways in which language contributes to poetic structure. For every subsystem of grammar of which some elements define a verse form, other elements remain free to create poetic effects of other kinds: phrasal rhythms (Cureton 1992); syntactic suspensions (Austin 1984). And even the most traditional elements of verse are not necessarily used pervasively as verse forms, but sometimes only fragmentarily, or in traditional terminology ‘ornamentally’ rather than ‘structurally.’ In Shakespeare’s sonnets, for example, alliteration and syntactic parallelism come and go within a form versified by meter and rhyme, in a manner which is not fundamentally different from the way meter and rhyme come and go in poems of Eliot which are not versified at all. And not just the grammar but also the lexicon can be the source of significant patterns of repetition. But even as only a limiting case, discoveries of the nature of the relationship of versification to grammar provide remarkable evidence of how forms which seem the height of artifice may in fact be rooted in ways of perceiving which, if the hypothesis of universal grammar is correct, operate as naturally as vision or hearing (Fodor 1983). Such discoveries have consequences for poetic effects of all kinds, whether traditional or innovative, pervasive or fragmentary, natural or genuinely artificial.

Perhaps more strikingly, the focus on versification here has not touched on such fundamental functions of language as communication or expression, which are particularly complex and interesting in the case of poetry. To some extent, this reflects the observation that communication is not unique to language: it has been argued by Sperber and Wilson (1986), for example, that in ordinary language, the phonological and syntactic parsing of a sentence makes only a minimal contribution to what it actually communicates, which in fact depends on an open-ended, context-dependent process of general reasoning which unlike the structural analysis of grammar is common to how information of all kinds is interpreted. At the same time, however there is at least one way in which versification invites its own kind of reasoning: as Wimsatt (1954) notes, the repetitions which consititute versification consistently invite the question of how whatever is designated by similar forms might themselves be alike. In this way, as Jakobson (1956) suggests, there is a metaphorical way of thinking inherent in poetic structure, which is not only a matter of its meaning, but also of its form.

Bibliography:

- Austin T 1984 Language Crafted. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN

- Chomsky N 1965 Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Cureton R 1992 Rhythmic Phrasing in English Verse. Longman, London

- Fabb N 1997 Linguistics and Literature. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Fodor J 1983 Modularity of Mind. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Halle M, Keyser S J 1972 The iambic pentameter. In: Wimsatt W K (ed.) Versification: major language types. Modern Language Association, New York

- Hanson K, Kiparsky P 1996 A parametric theory of poetic meter. Language 72: 287–335

- Hanson K, Kiparsky P 1997 The nature of verse and its consequences for the mixed form. In: Reichl K, Harris J (eds.) Prosimetrum: cross-cultural perspectives on narrative in verse and prose. D. S. Brewer, Cambridge, UK

- Hayes B 1995 Metrical Stress Theory. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Holtman A 1994 A constraint-based approach to rhyme.Linguistics in the Netherlands 1994: 49–60

- Jakobson R 1971 Two aspects of language and two types of aphasic disturbances. In: Rudy S (ed.) Roman Jakobson: Selected Writings II. Mouton, The Hague, The Netherlands 239–59

- Jakobson R 1979 On the so-called vowel alliteration in Germanic verse. In: Rudy S (ed.) Roman Jakobson: Selected Writings V. Mouton, The Hague, The Netherlands 189–97

- Jakobson R 1981a Linguistics and poetics. In: Rudy S (ed.) Roman Jakobson: Selected Writings III. Mouton, The Hague, The Netherlands 19–51

- Jakobson R 1981b Grammatical parallelism and its Russian facet. In: Rudy S (ed.) Robin Jackobson: Selected Writings III. Mouton, The Hague, The Netherlands 98–135

- Jespersen O 1993 In: Jespersen, O Linguistica. Levin and Munksgaard, Copenhagen

- Kiparsky P 1970 Metrics and morphophonemics in the Kale ala. In: Freeman D C (ed.) Linguistics and Literary Style. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York 165–81

- Kiparsky P 1977 The rhythmic structure of English verse. Linguistic Inquiry 8: 189–247

- Kiparsky P 1981 The role of linguistics in a theory of poetry. In: Freeman D C (ed.) Essays in Modern Stylistics. Methuen, London 9–23

- Kiparsky P 1987 On theory and interpretation. In: Fabb N, Attridge D, Durant A, MacCabe C (eds.) The Linguistics of Writing. Methuen, New York 185–98

- Kiparsky P 1989 Sprung rhythm. In: Kiparsky P, Youmans G (eds.) Phonetics and Phonology, Vol. 1: Rhythm and Meter. Academic Press, San Diego, CA

- Liberman M, Prince A 1977 On stress and linguistic rhythm. Linguistic Inquiry 8: 249–336

- Malone J 1987 Muted euphony and consonant matching in Irish verse. General LinguisticsI 27: 133–43

- Saussure F 1983 Course in General Linguistics. Duckworth, London

- Sperber D, Wilson D 1986 Relevance. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Wimsatt W K 1954 One relation of rhyme to reason. In: Wimsatt W K (ed.) The Verbal Icon. Kentucky University Press, Lexington, KY

- Youmans G Milton’s meter. In: Kiparsky P, Youmans G (eds.) Phonetics and Phonology, Vol. 1: Rhythm and Meter. Academic Press, San Diego, CA

- Zwicky A 1976 Well, this rock and roll has got to stop. Junior’s head is hard as a rock. Chicago Linguistic Society 12: 676–97