Sample Language And Social Class Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Linguists have known for some time that differences in language are tied to social class. Ross (1954) suggested that certain lexical and phonological differences in English could be classified as U (upper class) or non-U (lower class), e.g., serviette (non-U) vs. table-napkin (U), one of the best known of all linguistic class-indicators of England at the time.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Similarly, in the United States, some surveys of regional dialect recognized the importance of social status in geographical variation, and distinguished three categories of subjects based on the fieldworker’s classification: Type I—little formal education, little reading and restricted social contacts; Type II—better formal education (usually high school) and/or wider reading and social contacts; and Type III—superior education (usually college), cultured background, wide reading and/or extensive social contacts. These types correspond roughly to social status.

Until the 1960s, however, most studies of variability were concerned primarily with regional variation or dialectology, following a tradition established in the nineteenth century. These studies concentrated their efforts on documenting the rural dialects which it was believed would soon disappear. Only during the latter half of the twentieth century would the concern for status-based differences in language become a primary rather than a secondary focus, when sociolinguists turned their attention to the language of cities, where an increasing proportion of the world’s population lives in modern times. The rise of urbanization is connected with an increase in social stratification reflected in linguistic variation.

1. Beginnings Of Sociolinguistics

Research focusing on social dialects is sometimes referred to as social dialectology, and occupies a central place in quantitative sociolinguistic research on urban speech varieties, beginning with William Labov’s (1966) work in New York City. He was the first to introduce a systematic methodology for investigating social dialects and the first large-scale sociolinguistic survey of an urban community. Unlike previous dialectological studies, which generally chose one person (usually an older male) as representative of a particular area, this survey was based on tape-recorded interviews with 103 people who had been chosen by random sample as being representative of the various social classes, ages, ethnic groups, etc., to be found in New York City. This approach solved the problem of how any one person’s speech could be thought of as representing a large urban area.

Previous investigations had concluded that the speech of New Yorkers appeared to vary in a random and unpredictable manner. Sometimes they pronounced the names Ian and Ann alike and sometimes they pronounced post-vocalic /r/ (i.e., r following a vowel) in words such as car, while at other times they did not. This fluctuation was termed ‘free variation’ because there did not seem to be any explanation for it. Labov’s study and subsequent ones modeled after it, however, showed that when such free variation in the speech of and between individuals was viewed against the background of the community as a whole, it was not free, but rather conditioned by social factors such as social class, age, sex, and style in predictable ways. Thus, while idiolects (or the speech of individuals) considered in isolation might seem random, the speech community as a whole behaved regularly. Using these methods, one could predict that a person of a particular social class, age, sex, etc., would pronounce post-vocalic /r/ a certain percent of the time in certain situations.

Through the introduction of these new methods for investigating social dialects by correlating sociolinguistic variables with social factors, sociolinguists have been able to build up a comprehensive picture of social dialect differentiation in the United States and Britain in particular, and other places, where these studies have since been replicated.

2. Methods

In order to demonstrate a regular relationship between social and linguistic factors, we have to be able to measure them in a reliable way. Of the principal social dimensions sociolinguists have been concerned with (e.g., social class, age, sex, style, and network), social class has probably been the most researched. Patterns of social class differentiation are often assumed to be fundamental and other so-called sociolinguistic patterns of variation, e.g., stylistic and gender variation, are regarded as derivative of them (Labov 1972).

Many sociolinguistic studies have followed the generally accepted sociological practice of relying on indicators of social status, such as education, occupation, income, etc., grouped individuals into social classes on the basis of these factors, and then looked to see how certain linguistic features were used by each group. The method used in New York City to study the linguistic features was to select items which could be easily quantified; in particular, phonological variables such as post-vocalic /r/, which was either present or sent. This was one of the first features to be studied in detail by sociolinguists.

3. Results

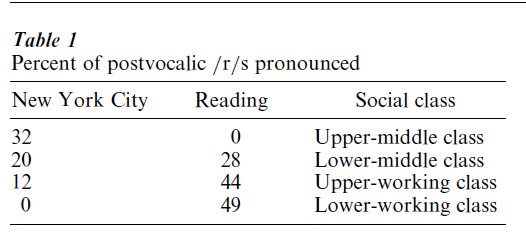

Varieties of English can be divided into two groups with respect to their treatment of this variable: those that are r-pronouncing (rhotic) and those that are not r-pronouncing (non-rhotic). Today in Britain, accents that have lost postvocalic /r/ as a result of linguistic change generally have more prestige than those, like Scottish English, that preserve it. In many parts of the United States the reverse is true, although this has not always been the case. Table 1 compares the pro- nounciation of postvocalic /r/ in New York City with that of Reading, England. The results show that in New York City the lower one’s social status, as measured in terms of factors such as occupation, education, and income, the fewer postvocalic /r/ s one uses, while in Reading the reverse is true. Like many features investigated by sociolinguists, the pronounciation of postvocalic /r/ shows a geographically as well as socially significant distribution.

Just as the diffusion of linguistic features may be halted by natural geographical barriers, it may also be impeded by social class stratification. Similarly, the boundaries between social dialects tend for the most part not to be absolute. The pattern of variation for postvocalic /r/ shows ‘fine stratification’ or continuous variation along a linguistic dimension (in this case a phonetic one) as well as an extralinguistic one (in this case social class). The indices go up or down in relation to social class, and there are no sharp breaks between groups. A major finding of urban sociolinguistic work is that differences among social dialects are quantitative and not qualitative.

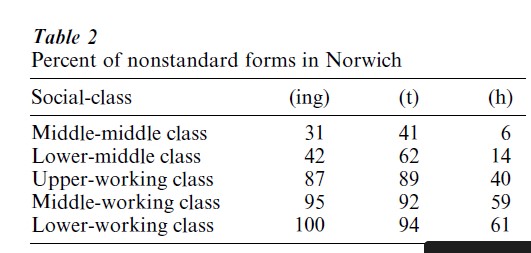

There are many other variables in English which show similar sociolinguistically significant distributions, such as those studied by Trudgill (1974) in Norwich in an urban dialect study modeled after the New York research. Table 2 shows the results for (ing), (t) and (h). The numbers show the percentage of nonstandard forms used by different class groups. The variable (ing) refers to alternation between alveolar /n/ and a velar nasal /c/ in words with -ing endings such as reading, singing, etc. The lower a person’s social status, the more likely he/she is to use a higher percentage of alveolar rather than velar nasal endings. This is often referred to popularly as ‘dropping one’s g’s,’ and is a well-known marker of social status over most of the English-speaking world.

The variable (h) refers to alternation between h and lack of /h/ in words beginning with /h/ such as heart, hand, etc. Unlike received pronunciation (RP), most urban accents in England do not have initial /h/ or are variable in their usage of it. For these speakers who ‘drop their h’s,’ art and heart are pronounced the same. Again, the lower a person’s social status, the more likely he she is to drop h’s. Speakers in the north of England, Scotland and Ireland retain /h/, as do speakers of American English. The variable (t) refers to the use of glottal stops instead of /t/, as in words such as bottle, which are sometimes stereotypically spelled as bot’le to represent the glottalized pronounciation of the medial /t/ . Most speakers of English glottalize final t in words such as pat, and no social significance is attached to it. In many urban dialects of British English, however, glottal stops are more widely used, particularly by younger working class speakers in London, Glasgow, etc.

By comparing the results for the use of glottal stops in Norwich with those for (ing) and (h), some interesting conclusions can be drawn about the way language and social class are related in this English city. Looking first at frequency, even the middle class in Norwich uses glottal stops very frequently, i.e., almost 50 percent of the time, but this isn’t true of (h). There is of course no reason to assume that every instance of variation in language will correlate with social structure in the same way or to the same extent. Most sociolinguistic variables have a complicated history. Some variables will serve to stratify the population more finely than others; and some cases of variation do not seem to correlate with any external variables, e.g. the variation between i and ε in the first vowel of economic is probably one such instance. Phonological variables tend to show fine stratification and there is more socially significant variation in the pronunciation of English vowels than in consonants.

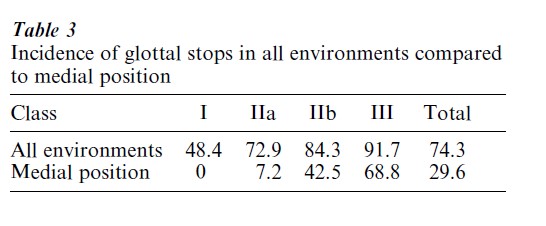

In the case of glottal stop usage, what is socially significant is how frequently a person uses glottal stops in particular linguistic and social contexts. The use of glottal stops is particularly socially stigmatized in medial position, e.g., bottle, butter. A hierarchy of linguistic environments can be set up which seems to apply to all speakers. Glottal stops are more likely to occur in the following environments.

Most frequent

Word final +consonant e.g., that cat

Before syllabic nasal e.g., button

Word final +vowel e.g., that apple

Before syllabic /l/ e.g., bottle

Least frequent

Word medially e.g., butter

Although all speakers are affected by the same internal constraints in the same way, they apply at different frequency levels, depending on social class member- ship and other external factors. Table 3 shows the incidence of glottal stops in relation to social class in Glasgow for all environments compared with that occurring only in medial position (Macaulay 1977). Class I is the highest and contains professional people, while Class III is the lowest and contains unskilled workers. The results show that glottal stops are the norm for this community (74.3 percent), if we look at all the environments. Even the highest social class uses glottal stops nearly half the time, and the lowest class, almost all the time. However, if we look at medial position, the highest social class uses no glottal stops in this environment, while the lowest class uses 68.8 percent.

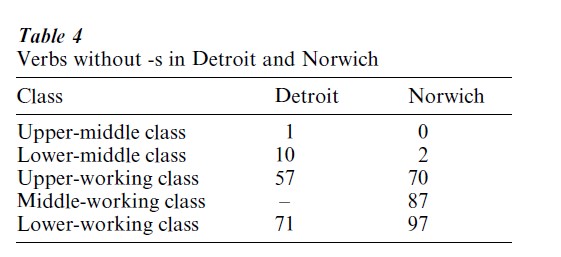

Although grammatical variables have been less frequently studied than phonological ones, they have tended to show sharp stratification; that is, they display a large social barrier between the middle class and the working class. Table 4 shows the results of a study of a grammatical variable in Detroit (Wolfram 1974) and Norwich (Trudgill 1974). The variable concerns the use of nonstandard third person singular present tense verb forms without -s, e.g., he go. Only working class speakers use these forms with any great frequency and this is more so in Norwich than in Detroit. The gap between the middle and working class norms is also greater in Norwich than in Detroit, reflecting the greater social mobility of the American social system. There are also other varieties of British English, e.g., in parts of the north, south-west and south Wales, where the present tense paradigm is regularized in the opposite direction and all persons of the verb takes -s, i.e., I goes, you goes, he goes, etc.

4. Social Class Differentiation In Relation To Other Sociolinguistic Patterns

The intersection of social and stylistic continua is one of the most important findings of quantitative sociolinguistics: namely, if a feature occurs more frequently in working class speech, then it will occur more frequently in the informal speech of all speakers. There are also strong correlations between patterns of social stratification and gender, with a number of now classic findings emerging repeatedly. One of these sociolinguistic patterns is that women, regardless of other social characteristics such as class, age, etc., tend to use more standard forms than men.

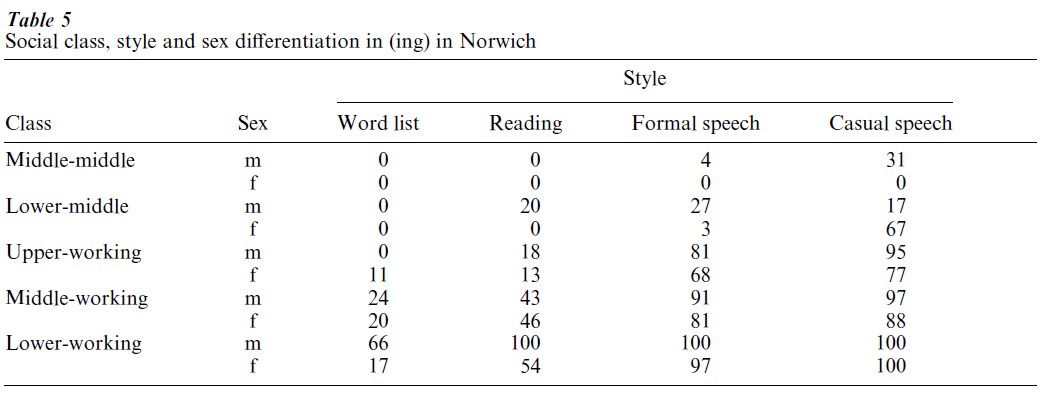

Table 5 shows the results of Trudgill’s (1974) study in Norwich of the variable (ing), i.e., alternation between alveolar /n/ and a velar nasal /c/ in words with -ing endings such as reading, singing, etc. in relation to the variables of social class, style, and sex. The scores represent the percent of nonstandard forms used by men and women in each social group in four contextual styles, i.e., when reading a word list, reading a short text, formal speech, and casual speech.

Generally speaking, the use of nonstandard forms increases the less formal the style and the lower one’s social status, with men’s scores higher than women’s. Although each class has different average scores in each style, all groups style-shift in the same direction in their formal speech style; that is, in the direction of the standard language. This similar behavior can be taken as an indication of membership in a speech community sharing norms for social evaluation of the relative prestige of variables. All groups recognize the overt greater prestige of standard speech and shift towards it in more formal styles.

Summing up these sociolinguistic patterns involving social class, gender, and style, sociolinguists would reply to the question of who is likely to speak most nonstandardly in a community: working-class men speaking in casual conversation. Conversely, middleclass women speaking in more formal conversation are closest to the standard. In Table 5, for instance, we can see that middle-middle-class women in word-list style never use the nonstandard form, while lower working-class men use it all of the time. Note, however, that the differences between men and women are not equal throughout the social hierarchy. For this variable they are greatest in the lower middle and upper working class. Such patterns reveal basic linguistic fault lines in a community, and are indicative of the uneven spread of the standard and its associated prescriptive ideology in a speech community. Similar results have been found in other places, such as Sweden and the Netherlands.

5. Social Class Differentiation And Language Change

Because variability is a prerequisite for change, synchronic variation may represent a stage in long-term change. By examining the way in which variation is embedded into the social structure of a community, we can chart the spread of innovations just as dialect geographers mapped variation and change through geographical space.

Sociolinguists have distinguished between ‘change from above’ and ‘change from below’ to refer to the differing points of departure for the diffusion of linguistic innovations through the social hierarchy. Change from above is conscious change originating in more formal styles and in the upper end of the social hierarchy, and change from below is below the level of conscious awareness originating in the lower end of the social hierarchy. Gender is critical here too. Women, particularly in the lower middle class, lead in the introduction of new standard forms of many of the phonological variables studied in the United States, the UK and other industrialized societies such as Sweden, while men tend to lead in instances of change from below.

Where hypercorrection occurs, as with post-vocalic /r/ in New York City, the lower middle class shows the most radical style shifting, exceeding even the highest group in their use of the standard forms in the most formal style. The behavior of the lower middle class is governed by their recognition of an exterior standard of correctness and their insecurity about their own speech. They see the use of postvocalic /r/ as a prestige marker of the highest social group. In their attempt to adopt the norm of this group, they manifest their aspirations of upward social mobility, but they overshoot the mark. The clearest cases of hypercorrection occur when a feature is undergoing change in response to social pressure from above, i.e., a prestige norm used by the upper class. In New York City the new /r/ pronouncing norm is being imported into previously non-rhotic areas of the eastern United States. Hypercorrection by the lower middle class accelerates the introduction of this new norm. The variable (ing), on the other hand, has been a stable marker of social and stylistic variation for a very long time, and does not appear to be involved in change and hence does not display hypercorrection.

Bibliography:

- Chambers J K 1995 Sociolinguistic Theory. Linguistic Variation and its Social Significance. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Labov W 1966 The Social Stratification of English in New York City. Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, DC

- Labov W 1972 Sociolinguistic Patterns. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA

- Macaulay R K S 1977 Language, Social Class, and Education. A Glasgow Study. University of Edinburgh Press, Edinburgh, UK

- Ross A S C 1954 Linguistic class indicators in present-day English. Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 16: 171–85

- Trudgill P 1974 The Social Differentiation of English in Norwich. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Wolfram W 1974 A Sociolinguistic Description of Detroit Negro Speech. Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, DC