Sample Grammatical Number Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Number is often taken to be a relatively straightforward category. It is often used as the textbook illustration of an inflectional category, and the situation in languages like English is believed by many to be the normal if not the only one. English makes a semantic distinction, and a formal distinction between, for instance, cat and cats, child and children. In fact the number category reveals many surprises, and the system found in English is a rather extreme one, when seen within the space of possibilities established from a survey of the languages of the world. We shall consider characteristics of the English system in turn, showing some of the ways in which it is typical or atypical. We shall give greatest prominence to the question of number values.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Nominal And Verbal Number

In English number is a nominal category, it involves the distinction between instances such as cat and cats. When it appears on verbs, this is by agreement with a subject noun phrase, as in the children were playing happily. The plural verb still indicates the number of children, and not the number of playing events. There are many languages which have verbal number, that is, where the number of the verb indicates the number of events (see Durie 1986 for examples).

2. Number As An Obligatory Category

Number is an obligatory category in English. If someone says, there’s a isitor waiting to see you, when there are several, this is misleading and inappropriate. In many languages, however, the use of the plural is not obligatory, but is used when it is important to mark number. One example is the Cushitic language Bayso:

- Bayso (Dick Hayward, personal

communications, Corbett and Hayward 1987)

luban foofe

lion.GENERAL watched.1SG

‘I watched lion’ (it could be one, or more than

that)

Another language, from many examples, is the Arawak family language Bare of Venezuela and Brazil (Aikhenvald 1995, pp. 18–19).

3. The Nominals Involved In The Number System

In English the majority of nominals can mark number, from the personal pronouns and nouns denoting persons (like woman) down to those denoting inanimate objects like door, and even to some denoting abstracts like hour. Many languages restrict the number opposition to fewer nominals, namely those which are high in animacy (Smith-Stark 1974). Thus in Slave (an Athapaskan language spoken in parts of the Northwest Territories, British Columbia, and Alberta, Canada) number may be marked on the noun phrase provided the noun denotes a human or a dog (Rice 1989, p. 247).

4. The Semantics Of Number

As long as we stay with innocent examples like English cat and cats, the semantics of number look clear, since cats is appropriate for more than one instance of cat. In fact there are many concealed difficulties: a concise overview of work on number within formal semantics can be found in Link (1998), who shows how the study of plurals relates to different movements in linguistic semantics, and provides a substantial Bibliography:.

If we move from ordinary plurals to consider I vs. we, it becomes clear that here we have an ‘associative’ use of the plural; we is most often used for ‘I and other(s) associated with me.’ At the other end of the Animacy Hierarchy, nouns like coffee have a plural, provided they are recategorized: if coffee denotes a type, or a typical quantity of coffee, then there is an available plural, as in: she always keeps three different coffees, and we’ e ordered two teas and three coffees.

5. Number Values

A striking way in which English is limited in its number system is in terms of the number values. In English we can distinguish only between singular and plural. Many languages have more distinctions, and it is these on which we shall concentrate.

5.1 The Dual

A common system is one in which singular and plural are supplemented by a dual, to refer to two distinct real world entities. Examples are widespread. We will take Central Alaskan Yup’ik, as spoken in the southwestern Alaska (Corbett and Mithun 1996); the number forms are: singular qayaq ‘kayak,’ dual qayak ‘two kayaks,’ and plural qayat ‘three or more kayaks.’ The addition of the dual has an effect on the plural, which is now used for three or more real world entities, and more generally a change in system gives the plural a different meaning.

5.2 The Trial

While the dual refers to two distinct real world entities, the trial is for three, and it occurs in systems with the number values: singular, dual, trial, and plural. This system is found in Larike, a Central Moluccan language spoken on the western tip of Ambon Island, Central Maluku, Indonesia. (Central Moluccan forms part of the Central Malayo–Polynesian subgroup of Austronesian.) This example is from Laidig and Laidig (1990, p. 7):

- Kalu iridu-taeu au-na-wela

if 2.TRIAL-NEG-go 1.SG-IRR-go.home

‘If you three don’t want to go, I’m going home.’

In this language the dual and trial forms can be traced back to the numerals ‘two’ and ‘three,’ and the plural comes historically from ‘four.’ Such developments are fairly common in Austronesian languages. Sometimes the term ‘trial’ is used according to the form of the inflections (derived historically from the numeral three), even when the forms are used currently for small groups including those greater than three (and so are paucals) and sometimes the term is used according to meaning (for genuine trials). The Larike trial is a genuine trial, used for exactly three (Laidig and Laidig 1990, p. 92).

5.3 The Paucal

Paucals are used to refer to a small number of distinct real world entities, somewhat akin to the English quantifier ‘a few’ in meaning. There is no specific upper bound on the use of paucals (their lower bound will vary according to the system in which they are found). Let us return to the Cushitic language Bayso. Besides the general number forms (as in (1), where number is not specified), there are also singular, paucal, and plural. Here is the paucal:

- Bayso (Dick Hayward, personal

communications, Corbett and Hayward 1987)

luban-jaa foofe

lion-PAUCAL watched.1.SG

‘I watched a few lions’

The paucal is used in Bayso for reference to a small number of individuals, from two to about six. (Bayso has this system in nouns but not in pronouns.) The Bayso system is rare; normally the paucal is found together with a dual, so that the number values are singular, dual, paucal, and plural. This widespread system is found, for example, in Yimas, a Lower Sepik language spoken in the Sepik Basin of Papua New Guinea (Foley 1991, p. 216).

5.4 The Largest Systems

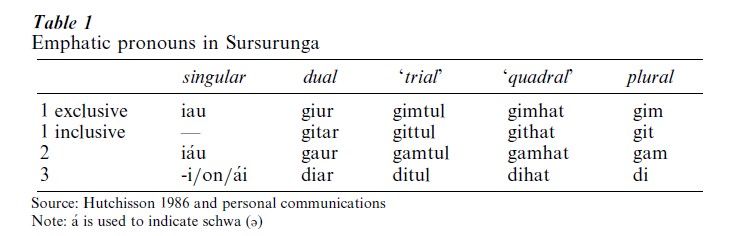

It is worth asking what is the largest system of number values. There are claims in the literature for languages with a quadral, for four distinct real world entities, thus giving a system of five number values. It is established that five number values can indeed be found, but the evidence specifically for a quadral is less clear. All the claims come from within the Austronesian family and the best documented case is Sursurunga (Hutchisson 1986, and personal communications), spoken in southern New Ireland. The forms labeled quadral are restricted to the personal pronouns, but are found with all of them, the first person (inclusive and exclusive), the second, and third (Table 1).

Here is an example of a quadral form in use (we will retain the traditional label ‘quadral,’ until we have justified replacing the term for Sursurunga):

- Sursurunga (Hutchisson 1986 and personal

communications)

gim-hat kawan

1.EXCL-QUADRAL maternal.uncle:nephew

niece

‘we four who are in an uncle-nephew niece

relationship’

The ‘quadral’ has two additional uses. First, in Sursurunga plural pronouns are never used with terms for dyads (kinship pairings like uncle-nephew niece). Here the ‘quadral’ is used, for a minimum of four, and not just for exactly four (Hutchisson 1986, p. 10). Second, in hortatory discourse, the speaker may use the first person inclusive ‘quadral’ in order to suggest joint action including the speaker, even though more than four persons are involved. These two special uses of the ‘quadral’ account for the majority of instances of its use. According to its meaning, the term ‘quadral’ is not appropriate. Rather the forms would be better designated ‘paucal.’

Let us now consider the rest of the system of Sursurunga (data and judgments from Don Hutchisson, personal communications). The dual is used quite strictly for two people. It is also used for the singular when the referent is in a taboo relationship to the speaker. This is a special use; the dual’s main use is as a regular dual. The trial will be used for three. However, it is also used for small groups, typically around three or four, and for nuclear families of any size. It is therefore not strictly a trial, rather it could be labeled a paucal (an appropriate gloss would be ‘a few’). We noted earlier that this is a frequent development for the trial. The ‘quadral,’ as we have just seen, is used primarily in different ways with larger groups, of four or more (an appropriate gloss would be ‘several’). This too would qualify as a paucal; we therefore have two paucals in Sursurunga, a paucal (traditionally ‘trial’) and a greater paucal (traditionally ‘quadral’). The plural, as we would expect, is for numbers of entities larger than what is covered by the greater paucal, however, there is no strict dividing line (certainly not at the number five). Using semantic labels, we might represent the system in Sursurunga as having: singular, dual, paucal, greater paucal, and plural. Sursurunga has a well-documented five-value number category. There are certainly other languages with five number values; we do not have such detailed information as for Sursurunga and there is no certain case of a quadral: it seems that in all cases the highest value other than plural in such systems can be used as a paucal. Besides the split in the paucal, we may also find a split in the plural, with ‘greater plurals’ of different types, as for instance in Mokilese (Harrison 1976). Greater plurals may imply an excessive number or else all possible instances of the referent. They are as yet poorly researched, except in a few languages.

6. Conclusion

Number is indeed a much more complex category than is generally recognized, and the English system, though a common one, is at one extreme of the typological space. We noted that number may be a verbal category as well as a nominal one (but the possibilities are rather more restricted for verbal number). We also saw that number need not be obligatory, that the range of items which distinguish number varies dramatically from language to language, that the semantics of number are affected by the particular item involved, and that the values of the number category can be just two or, in various combinations, up to five. More complex issues, which we have not been able to address here, include various interactions, notably between the forms of marking of number, the particular nominals which distinguish number in a given language, and the systems of number values. For these issues see Corbett (2000).

Bibliography:

- Aikhenvald A 1995 Bare (Languages of the World Materials 100). Lincom Europa, Munich, Germany

- Corbett G G 2000 Number. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Corbett G G, Hayward R J 1987 Gender and number in Bayso. Lingua 73: 1–28

- Corbett G G, Mithun M 1996 Associative forms in a typology of number systems: Evidence from Yup’ik. Journal of Linguistics 32: 1–17

- Durie M 1986 The grammaticization of number as a verbal category. In: Vassiliki N, VanClay M, Niepokuj M, Feder D (eds.) Proc. of the Twelfth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: February 15–17, 1986. University of California, Berkeley, CA, pp. 355–70

- Foley W A 1991 The Yimas Language of New Guinea. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

- Harrison S P, Albert S Y 1976 Mokilese Reference Grammar. University Press of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI

- Hutchisson D 1986 Sursurunga pronouns and the special uses of quadral number. In: Wiesemann U (ed.) Pronominal Systems (Continuum 5). Narr, Tubingen, Germany, pp. 217–55

- Laidig W D, Laidig C J 1990 Larike pronouns: Duals and trials in a Central Moluccan language. Oceanic Linguistics 29: 87–109

- Link G 1998 Ten years of research on plurals—where do we stand? In: Hamm F, Hinrichs E (eds.) Plurality and Quantification. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 19–54

- Rice K 1989 A Grammer of Slave. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin

- Smith-Stark T C 1974 The plurality split. In: La Galy M W, Fox R A, Bruck A (eds.) Papers from the Tenth Regional Meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society, April 19–21, 1974. CLS, Chicago, pp. 657–71