Sample Syntactic Constituent Structure Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Although we perceive sentences in natural languages such as English, Chinese, Hopi, etc., as mere sequences of words, as in the division of Example (1) into six words, much if not all of language that is of interest involves structure that goes beyond the segmentation of the speech-stream into words. The grouping of words into phrases is called constituent structure.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

- Old men and women visited Martha.

Constituent structure can be shown to determine the meanings of sentences, for example. Every theory of meaning requires that the account of meaning obeys Frege’s Principle of Compositionality (Frege 1952), which states that the meaning of a complex expression is determined by its parts. In this connection, it is noteworthy that the sentence in (1) above is ambiguous, the ambiguity turning on the question of whether the women are old or not. In other words, the sequence old men and women has two interpretations, which can be represented with two different structures for the sequence. The two structures can be represented as follows:

(2) Old (men and women) visited Martha.

(3) (Old men) and women visited Martha.

In short, the ambiguity in (1) hinges on whether (a) the conjunction and is joining two nouns, the unity of which is modified by the adjective old, or (b) the conjunction and is joining a noun with an adjective-plus-noun sequence. The example shows that one cannot specify the meaning of a sentence such as (1) by simply stringing the meanings of the words together. In this sense, natural languages such as English have a great deal in common with most systems of formal logic, which interpret sentences of logic by means of parentheses, which group the ‘words’ of the logical expression (Allwood et al. 1977). An example shows this for prepositional calculus, the simplest logical language. Beginning logic students are asked to determine the truth of the following expression, simplified here, reflecting different groupings of the logical words:

(4) Not ( p or q) is equivalent to (Not p) or q.

Where p and q reflect simple propositions, which can be either true or false.

If two expressions are logically equivalent, they always have the same truth value. To determine whether or not (4) is true, therefore, one must assign p and q all possible combinations of truth values (both true, both false, p true and q false, or p false and q true), and given the semantic rules for or and not, one sees whether in all four cases, Not ( p or q) has the same truth value as (Not p) or q.

The two sentences do not have the same truth value consistently, indicating that the parentheses, which reflect the grouping of elements, affect the meaning. Natural languages are similar to logical languages, in the sense that the meanings of sentences in both types of language depend on groupings of words—in short, constituent structure. There is a question, however, of whether or not constituent structure in natural language is represented in the same way that it is represented in logic. In logic, when complex sentences are constructed, as in (4), they are constructed in a series of steps, so that Not ( p or q) is built by first disjoining p and q, and then negating the result. The rules of formation are called the syntactic rules, and hence syntax, in both logic and in natural language, is just the principles of sentence formation, as opposed to semantics, which interprets the results of the syntax. In logic, each syntactic rule is followed by a semantic rule. Hence, when the expression p orq is formed, p or q is interpreted. When p orq as a unit is combined with Not, the meaning of Not combines with the meaning of p or q to determine the meaning of the whole expression Not ( p or q). Given that each syntactic rule is followed by a semantic rule, it is unnecessary to actually represent the grouping by means of parentheses in a structure. The process of formation, known as a derivation, is what actually determines the meaning. The parenthesis is simply a way of describing the derivation of this sequence.

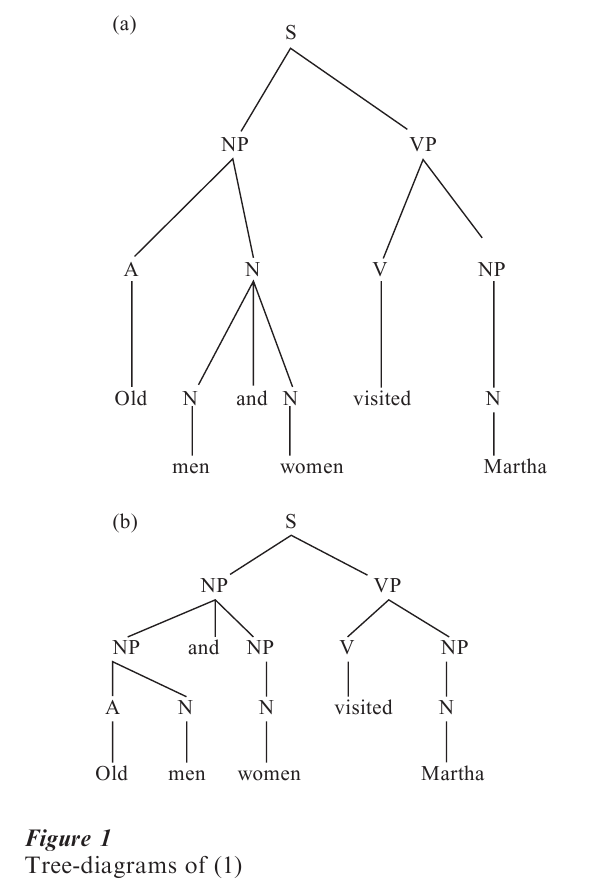

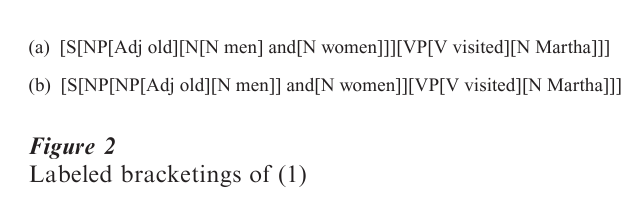

An open question, therefore, is whether constituent structure in natural language needs to be represented in an actual structure, or whether the process of forming sentences is enough to determine meanings of sentences. Most linguists assume that constituent structure must be represented by positing structures for sentences known as phrase-markers, which are usually given as tree diagrams or labeled bracketings. The two tree-diagrams for (1), corresponding to both structures, are given Fig. 1, and they are equivalent to the labeled bracketings in Fig. 2.

A word of explanation is in order. NP stands for n(oun) p(hrase), VP for v(erb) p(hrase), and S for sentence. The diagrams in (7) and (8) are called phrase-markers, which are representations of the structures of sentences.

One piece of evidence for the words of the sentence being grouped has been based on meaning. How-ever, there is evidence from a variety of sources for constituent structure. The approach to linguistics developed in the United States since roughly the 1930s (Bloomfield 1933), known as structuralism, has concentrated on the development of rigorous procedures for isolating and classifying the units of language, such as grammatical categories. The method for classifying words into grammatical categories is based not on meaning but on distribution. A grammatical category (known from traditional grammar as a part of speech) is defined thus:

(5) A grammatical category is a class of elements whose members are mutually substitutable (i.e., interchangeable without loss of acceptability of the result) in a sufficiently wide range of environments.

So the class of, for instance, nouns is the class of elements that can appear in the environments in which nouns can appear, so that, for instance, books, tables, chairs, sincerity, truth, etc., can appear in enough of the same slots in a sentence to the exclusion of other words such as from, at, and, and laugh to justify putting them into a group, and calling this group nouns.

The definition of grammatical category given in (5), however, which partitions the set of single words into classes, also defines sequences of words into members of the same grammatical class as single words. To illustrate, consider the underlined spaces in (6):

(6) (a) _____might interest me.

(b) I talked about_____.

(c) He likes_____.

Just as one can substitute the class of nouns that were exemplified above for one another, so one can substitute, for example big books, the books, the big books, the big books about Nixon for the word books in all of the environments in (8), as well as many others, leading us to conclude, from the definition of grammatical category given in (7), that the italicized sequences in this paragraph are all members of the same grammatical class as the simple noun books. We nevertheless must distinguish between simple members of a grammatical category, such as nouns, and the more developed phrasal instances of these grammatical categories. Hence, we use the term ‘noun phrase’ for the latter, and the simple term ‘noun’ for the former.

The same considerations that were illustrated above for noun phrases lead us to establish the other phrasal categories, such as verb phrases, adjective phrases, and prepositional phrases. There are a variety of processes that operate in grammar, which can move or delete linguistic elements. An example of movement is given in (7), and an example of deletion is given in (8):

(7) (a) Though he may laugh, it won’t matter.

(b) Laugh though he may, it won’t matter.

(8) (a) John laughed, and Bill laughed as well.

(b) John laughed, and Bill did ______as well.

The (b) versions of (9) and (10) exemplify the movement and deletion of laugh. However, sequences of words can undergo these processes:

(9) (a) Though she may finish her homework, it won’t matter.

(b) Finish her homework though she may, it won’t matter.

(10) (a) John finished his homework, and Bill finished his homework as well.

(b) John finished his homework, and Bill did ______as well.

The sequences of elements that undergo such grammatical processes are those sequences we would want to posit as constituents, so the movement process that is exemplified in (11b) is said to move verb phrases, and the deletion process at work in (12b) deletes verb phrases. For a variety of reasons, one would say that a verb phrase is being moved and deleted in (9b) and (10b), respectively, but the verb phrase is one that consists of a simple verb.

There is also evidence from the study of sentence processing in psycholinguistics for constituent structure. In one experimental paradigm (Fodor and Bever 1965), complex sentences (i.e., sentences with various types of subordinate clauses) are recorded, and clicks are superimposed on the recorded sentences by splicing a tape containing the click into a complex sentence. The location of the click was varied with respect to its location in the sentence, occurring from one syllable away from a clause boundary to a number of syllables away. For example, in sentence (11), the click would occur at various points away from the bolded clause boundary:

(11) John told Susan that Sally was hungry.

Experimental subjects always reported the click at the clause boundary, regardless of the click’s objective location. These results indicate a salience of a structural point within the sentence as a whole.

While there is thus a great deal of evidence for constituent structure for languages such as English, there is less evidence from other languages, such as Warlpiri, which exhibit free word order (Hale 1983). Such languages are usually informally termed ‘free word order’ languages, but the term does not denote a totally unified class of languages. Japanese (Saito 1985) and Hindi (Mahajan 1990), for example, allow relatively free word order phrases within simple sentences, but require that phrases occur together. Hence, one finds subjects, objects, and indirect objects occurring in any order relative to one another, but subjects must stay together, as must objects, indirect objects, and indeed any phrasal units. Warlpiri, on the other hand, shows much less cohesion, so that the various parts of what are considered for instance, noun phrases, can be separated from one another by material from outside the noun phrase. The cohesion of noun phrases in Japanese and Hindi provides evidence for constituent structure in these languages, and evidence exists that Japanese has a verb phrase, regardless of the free word order among major constituents (Saito and Hoji 1983). The word-order variation in Japanese and Hindi has been analyzed by Saito and Mahajan, respectively, as arising from movement of the noun phrases from a fixed basic position. It is much more difficult to make this type of analysis for the truly free word order languages such as Warlpiri. Baker (1995, 2000) has some suggestions. Languages with free word order of this sort have extensive case-marking, which would express the grammatical relations of the various noun phrases, so that the case-markers on what would be in English the parts of the noun phrase would signal the semantic units of Warlpiri sentences without making them constituents in the actual syntax.

Putting aside the question of the best treatment of truly free word order languages, we have seen that although a language is usually described as a set of strings (i.e., sequences of words) that is generated by a grammar, the strings are structured into constituents. Chomsky (1957) introduced the distinction between the weak generative capacity of a grammar, which is the set of strings that the grammar generates, and the strong generative capacity of the grammar, which is the set of structures that the grammar generates.

It is paradoxical that we only directly perceive the strings of a language, because most, if not all, of what is interesting about a language is defined in terms of strong generative capacity. We have seen that meaning is determined by structure, a hierarchical notion given by the constituent structure, rather than by linear order of words. Most grammatical operations have been shown crucially to implicate constituent structure, such as movement and deletion operations, as we have seen. Given that constituent structure is not directly perceptible, unlike linear order, it poses severe learnability problems, as pointed out by Pinker (1984), and is usually taken to be innate. This leads to a predicted universality of constituent structure, and this assumption has been used in recent years in work on comparative grammar, such as Pollock’s work on French vs. English verb movement (Pollock 1989). Here Pollock studies the placement of adverbs with respect to verbs in both languages, assumes that the adverb is generated in the same structural position in both languages, and attributes the different positions of the verbs with respect to the adverbs to the scope of a verb-movement rule that applies much more generally in French than in English. Pollock shows that the differences between French and English verbs with respect to their linear order vis-a-vis adverbs correlates with other differences between French and English verbs, suggesting that verbs in the two languages differ in their structural positions.

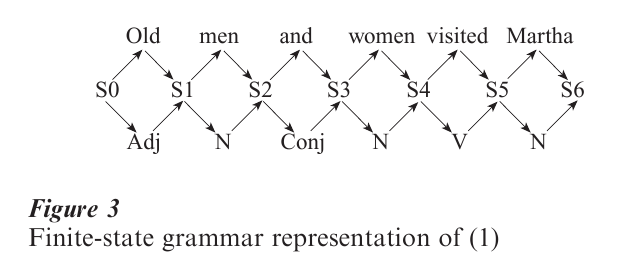

It is also worthwhile to consider an alternative description of English which does not posit constituent structure, a model described in Chomsky (1957) as a finite-state grammar, based on the work of Shannon and Weaver (1963) on information theory. This model views a grammar, in generating a sentence, as a machine which enters successive states when constructing a sentence, and each word that is added to the sentence as it is created puts the grammar into a different state. Each word can be described in terms of its possible continuations, and the machine starts in state S0. A finite state description of, for example, sentence (1) would be as shown in Fig. 3.

The basic idea of a finite-state grammar is that there are a finite number of states because there is a limit on the number of words in a possible sentence. There does not seem to be, in fact, a limit on the length of a sentence in English or any other language that is due to grammar. For example, it is possible for a sequence of adjectives to occur before a noun in English, as in (12):

(12) Tall, beautiful, intelligent, rich, affable people.

Because there is no bound on the number of adjectives that can occur before a noun, an English sentence can be of any length whatever. Finite-state grammars can account for this obstacle to finiteness by allowing certain word-classes to loop back upon themselves. However, while finite-state grammars can account for iteration of words, they cannot account for iteration of phrases, as in (13), as Chomsky (1957) points out:

(13) John thinks that Fred knows that Mary believes that Max pretended that Joe was hungry.

In this case, the potentially infinite length is due to the containment of a sentence, a phrasal unit, within another sentence.

Chomsky’s critique of finite-state grammars appeared shortly after an analogous critique occurred in psychology, in which Karl Lashley (1951) criticized associationism, which viewed behavior as being describable in terms of contiguous responses, so that, for example, going to the refrigerator to get a sandwich would be described, in associationist terms, as putting one step toward the refrigerator door, putting out one’s hand, opening it, grasping the refrigerator door handle, pulling it toward one, etc. Lashley noted that such a view did not take into account the notion of an over-arching plan. Lashley was arguing that thought required constituent structure, and the finite-state grammar could be viewed as the linguistic implementation of associationism.

Bibliography:

- Allwood J S, Andersson L G, Dahl O 1977 Logic in Linguistics. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Baker M C 1995 The Polysynthesis Parameter. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Baker M 2000 The natures of nonconfigurationality. In: Baltin M, Collins C (eds.) The Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Bloomfield L 1933 Language. H. Holt, New York

- Chomsky N 1957 Syntactic Structures. Mouton, The Hague, The Netherlands

- Fodor J A, Bever T G 1965 The psychological reality of linguistic segments. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 4: 414–20

- Frege G 1952 On sense and reference. In: Black M, Geach P (eds.) Translations from the Philosophical Writings of Gottlob Frege. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

- Hale K 1983 Warlpiri and the grammar of nonconfigurational languages. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 1: 5–49

- Lashley K 1951 The problem of serial order in behavior. In: Jeffress L A (ed.) Cerebral Mechanisms in Behavior: The Hixon Symposium. Wiley, New York

- Mahajan A 1990 The A – A-Bar Distinction in Syntax. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA

- Pinker S 1984 Language Learnability and Language Development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Pollock J-Y 1989 Verb movement, universal grammar, and the structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 365–424

- Saito M 1985 Some asymmetries in Japanese syntax and their theoretical implications. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA

- Saito M, Hoji H 1983 Weak crossover and move alpha in Japanese. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 1: 245–59

- Shannon C E, Weaver W 1963 The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, IL