Sample Morphology In Linguistics Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Introduction

Morphology is the study of word structure, the way words are formed and the way their form interacts with other aspects of grammar such as phonology and syntax. In many languages words assume extremely complex forms, and propositions requiring a complete sentence in English can be expressed as a single word. In other languages there is virtually no morphology, and notions corresponding to ‘plural of’ or ‘past tense of’ are conveyed by separate words. Surveys of the field are found in Carstairs-McCarthy (1992), Matthews (1991), Spencer (1991). Introductions to specific topics can be found in the chapters of Spencer and Zwicky (1998). The summary given here is expanded in Spencer (2000).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

2. The Concept Of ‘Word’

The ordinary term ‘word’ corresponds to several distinct notions. Consider the examples pick, picks, picked, picking. In one sense these are four distinct words, but in another sense they are four forms of a single word or ‘lexeme’ (which we can designate as PICK). The forms pick, picks are themselves ambiguous between verb forms and noun forms. Thus, there is a sense in which picks is one word form but corresponds to two lexemes, the verb PICK and the noun PICK. A more subtle form of ambiguity is illustrated by the lexeme CUT. The form cut has two legitimate grammatical descriptions: ‘base form of CUT’ and ‘past tense of CUT.’ Thus, cut is a single word form of a single lexeme but it represents two distinct ‘grammatical words.’ Finally, consider the expressions again and again. In normal speech these are completely indistinguishable, yet again consists of two words, which can be separated with an adjective: a significant gain. The two expressions can be called a single ‘phonological word.’ Normally, we expect a single word form to correspond to a single phonological word, but this is not the case with a gain. Another particularly dramatic instance of such a mismatch is illustrated by Tom’s a linguist. Here Tom’s is a single phonological word (a single syllable in fact) but corresponds to two distinct words, the noun subject ‘Tom’ and the main verb ‘is.’

3. The Lexeme Concept

The notion of lexeme corresponds to the lexicographer’s notion of ‘lexical entry.’ A lexeme is an abstract concept which unites information about the pronunciation and the meaning of a word, as well as about its grammatical properties. Thus, the lexeme CAT includes a phonological representation (/kat/) and a semantic representation (of whatever it is that ‘cat’ means). In addition, many would include the information that CAT is of syntactic category ‘noun.’ In the lexical representation for the verb CUT we would have to include the idiosyncratic information that its past tense/participle forms are irregular. For the (virtually synonymous) verbs STOP and CEASE the lexical representations have to include the information that both take a clause complement whose verb is in the -ing form (They stopped ceased studying) and that only cease but not stop can take an infinitive form (cf. They ceased to study but not * They stopped to study in the required sense). A lexeme is thus an elaborated sign, a pairing of sound form with meaning (together with other grammatical information).

PICK and WRITE are clearly different lexemes, and each has its set of forms. Consider the words unpick or rewrite. These are not forms of pick, write, rather they are newly derived lexemes, formed by adding un-, re to the beginning of the base form of the original verb. This adds some component of meaning to the old lexeme. The creation of new, complex lexemes by morphological devices such as this is derivational morphology. The formation of distinct forms of a single lexeme is inflectional morphology. This is a traditional and useful distinction, though one which can be very difficult to draw in practice, even in a language with relatively little morphology like English.

Derivational morphology often changes the part of speech of a word, so that we can create nouns from verbs (drive—driver), verbs from nouns ( flea—deflea), adjectives from nouns (dirt—dirty), and so on. It is often said that inflection cannot change the part of speech, but this is misleading. Thus, verbs often have participle forms and these behave very much like adjectives, serving to modify nouns, and in many languages agreeing with the noun just like any other adjective (English examples would be forms in -ing or -ed as hot running water, freshly picked apples). However, participles are generally regarded as forms of the verb, because they are not seen as creating a new lexeme. However, this is where the traditional distinction becomes difficult to draw, because of equivocation in traditional grammar over the meaning of inflected forms. For instance, it is generally said that picked means ‘past tense of PICK.’ But if that were true, picked would have a different meaning from picks, which means ‘present tense of PICK (with 3rd singular subject).’ But now it looks as though inflected word forms undergo a shift of meaning, which should make them into new lexemes.

The solution is to say that inflected forms do not convey meanings directly, but rather are associated with (abstract) features, such as [TENSE: Past] or [NUMBER: Plural]. These features are then interpreted semantically in various (sometimes complex and indirect) ways. Derivational processes, on the other hand, can be regarded as signs, adding their meaning to that of the base lexeme. This is not uncontroversial, however, and some linguists would argue that derivational meanings are every bit as indirect as inflectional meanings, and they would therefore not distinguish inflection from derivation.

For a given language, then, it may be useful to distinguish the inflectional functions (features) from the derivational meanings, though in practice the distinction is not always easy to draw. In many languages alternations such as drive—driver are extremely regular, to an extent that they might best be thought of as inflectional. On the other hand, in some languages only a handful of nouns have a plural form (Mandarin Chinese is an example), and this would suggest that plurals in such languages are cases of derivational morphology rather than inflection. Some argue that we must therefore distinguish two types of inflection, one which is purely featural (‘contextual inflection’), such as agreement inflections, and one which is given a direct semantic interpretation (‘inherent inflection’), such as plural or past tense inflections. However, it remains very difficult to distinguish inherent inflection from derivation.

4. Morphological Form

Words in English are frequently complex, consisting of identifiable units. One case is that of the compound word, such as snowball, blackbird, pickpocket. These consist of two or more words combined. However, they are not the same as syntactically formed phrases. This is clear from comparing the compound word blackbird with the phrase black bird. The stress in the compound falls normally on the first element, BLACKbird, while in the phrase it falls on the second, black BIRD. It is often the case that the meaning of the compound cannot be predicted solely from the meaning of the component words. Thus, a black bird has to be black (even if it’s a swan), but a blackbird could be brown, and a raven is not the same as a blackbird. Snowball and blackbird are kinds of ball and bird respectively. The words ball, bird are said to be the head of the compound (endocentric compounding). However, a compound such as pickpocket is not a kind of pocket and such a compound is not therefore headed (exocentric compounding). Compounding is very productive in English and it is possible to create new compounds in speech. Thus, a book describing the history of tea drinking could be described as the tea book. Compounding is also recursive, meaning that the process can feed itself. Thus, the author of the tea book would be the tea book author.

Languages differ in the compounds they permit. English has many compounds of the form train driver in which train appears to be the object of the verb drive in driver (so-called synthetic compounds). However, it is not normally possible to simply compound a noun with a verb: * Tom train-drives. However, just such a process, where the object is ‘incorporated’ into the verb, is very common in languages outside the Indo-European group.

French has very few compounds of the type snowball or blackbird but has a great many which resemble pickpocket. Pickpocket is clearly related to the phrase ‘to pick pockets’ and French also has a great many other fixed expressions which seem to derive from syntactic phrases, as in le va-et-vient, literally ‘the comes-and-goes,’ ‘comings and goings.’ This use of ‘frozen’ bits of syntax is a major way of forming new lexemes in a great many languages.

Compound words are intriguing in that they behave like a single word syntactically even though they are composed of more than one word (both in the sense of lexeme and word form). In many cases they can be difficult to distinguish from phrases or idioms. Other types of complex word are more obviously single word forms. Thus, picks, picked, picking clearly contain a base part or root followed by a suffix. Likewise, we can segment words such as re-write, un-happy, pre-war into a prefix and root. Affixation of this sort is the commonest device for conveying inflection and derivation. In addition to prefixes and suffixes, we sometimes find that simultaneous prefixation and suffixation convey a single grammatical meaning (circumfixation), as with the German past participle ge-…-t: In many languages an affix can appear inside the root rather than at its edge. Thus, in Tagalog, a verb root beginning with a vowel takes a prefix umin one of its inflected forms aral ‘teach’ um-aral. However, when the verb begins with a consonant the prefix appears as an infix, breaking up the integrity of the root: sulat ‘write’ s-um-ulat, gradwet ‘graduate’ gr-umadwet. Another, very common, process is that of reduplication. In many languages a grammatical meaning is signalled by repeating the word, as in Indonesian anak ‘child’ anak-anak ‘children,’ siapa ‘who,’ siapa-siapa ‘whoever.’ In other cases only part of the root is repeated, as in Tagalog sulat ‘write’ susulat ‘will write.’

The lexemes sing and song are related but by change of the root vowel (ablaut) rather than affixation. Moreover, the verb has past tense and past participle forms sang, sung with yet different vowels. In Semitic languages such as Arabic and Hebrew it is very common for inflected words to be formed by changing all the root vowels. In the plural of leaf, knife we see an alternation f ~ v: leaves, knives. In many languages alternations in the final or initial consonant are common and can be used without any affixation to signal grammatical meanings or functions (consonant mutation). The Celtic languages provide well-known examples of this, and other examples of changes in the sound shape being used to convey inflectional or derivational functions can be found in handbooks such as Spencer (1991).

5. The Morpheme Concept

The plural ending in dogs is pronounced /z/ , in cats it is /s/, while in horses it is /z/ (where the symbol /c/ represents the schwa, or reduced vowel; see Phonology). The difference in pronunciation is due to the final sounds of the roots dog, cat, and horse. Despite this difference it is clear that in one sense we are dealing with just one (abstract) suffix with three variant pronunciations. The variation is conditioned solely by the phonology of the root to which the suffix attaches and is a predictable consequence of English grammar. The abstract single plural ending is known as a morpheme, -z, and the three variants /z/ , /s / , /z/ are called allomorphs of that morpheme. Variation of this sort is referred to as allomorphy.

A long tradition holds that the plural morpheme is a sign consisting of a pronunciation (or rather a set of three pronunciations) and the meaning ‘plural.’ Thus, the meaning of cats is computed by combining the meaning of cat with that of ‘plural.’ Under this view, -z is a sign, a pairing of form ( /z, s,/ /z/ ) with meaning (‘plural’), and this effectively gives the morpheme the same status as a lexeme. Theories which rest on this assumption will be called ‘morphemic.’

There are three sets of problems with such a view, all of which feature deviations from the agglutinative process of adding signs together. One is that the form of a morpheme is often difficult to pin down. Thus, to obtain the past tense and past participle of sing we have to change the root vowel, sang, sung, but a vowel change is a process or a relationship between forms rather than a form itself. Even where it seems possible to isolate an affix there may be complications. Thus, in written we have an ending /n/ corresponding to the meaning ‘past participle’ (as in taken), but we also change the root vowel (cf. write /rait/ , written /ritn/). Which is ‘the’ past participle morpheme?

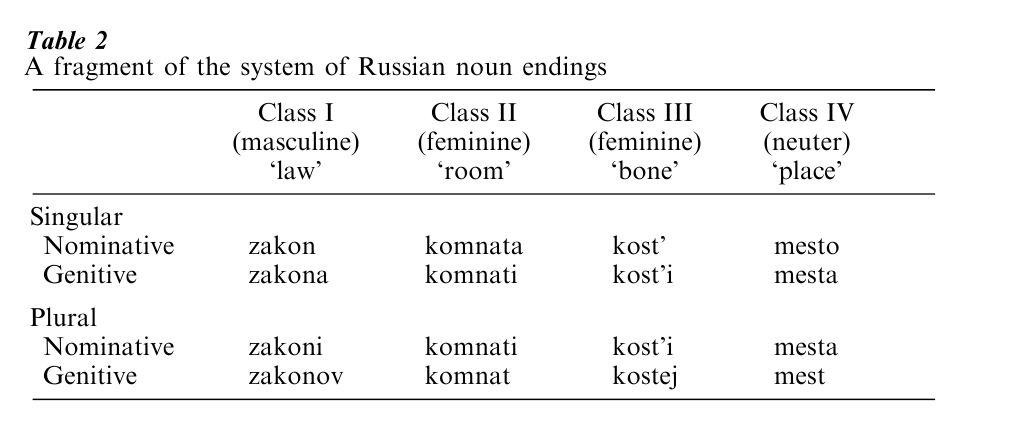

Another problem is that in complex morphological systems the overall meaning is often signalled by the relationships between word forms in the whole paradigm rather than in the meanings of individual morphemes. Russian nouns have six case forms and two numbers, singular and plural, with the case and number being signalled by various endings. The word komnata means ‘a room’ (nominative singular case, which we can think of as the basic form), while komnati is the genitive singular case meaning ‘of a room.’ By coincidence, komnati is also the nominative plural case, ‘rooms.’ However, for this class of nouns (but not others) the genitive plural ‘of rooms’ is komnat, in which there is no ending, just the bare root. This means we have to countenance a null or zero morpheme, which has no pronunciation at all, just a meaning ‘genitive plural (for the komnata class).’

More careful consideration shows that null morphemes must be very widespread. Thus, if we are to take seriously the idea that the complete meaning of a word form is given by its component morphemes then we should conclude that the singular cat must have a zero singular ending (otherwise, how would we know that the word denoted a single cat?) For very complex languages in which a word might potentially be furnished with a dozen or more affixes we regularly encounter such zero morphemes. This is suspicious, because there are no reliably recorded cases of zero lexemes (i.e., true lexemes whose basic phonological form is null).

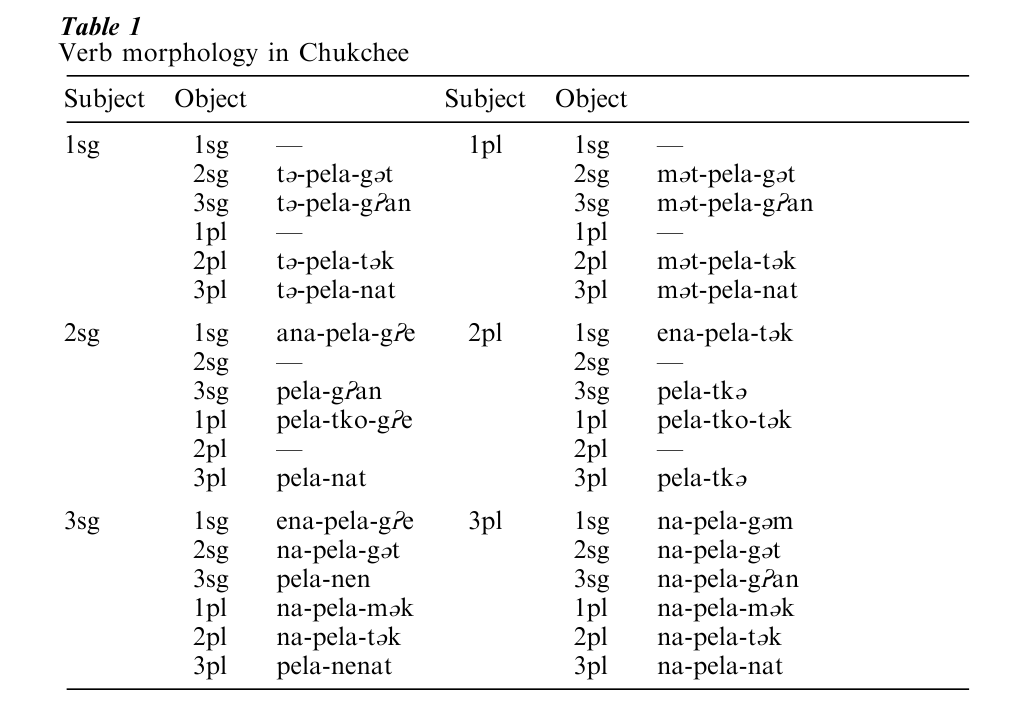

A variant of this second problem is encountered in morphologically complex languages. A typical instance can be seen in the verb morphology of Chukchee (spoken in NE Siberia). Verbs agree with both subject and object for person and number, as shown in the paradigm (Table 1) (the symbol is the glottal stop).

The forms t -pela-g an ‘I left him,’ m t-pela-g an, ‘we left him,’ pela-g an ‘you (sg.) left him,’ na-pela- g an ‘they left him’ show that the suffix -g an means ‘him,’ and the prefixes t -, m t and na denote subjects, 1sg, 1pl and 3pl respectively, with 2sg remaining unmarked. Thus far the system seems very regular (agglutinative). However, the form for ‘he left him’ is pela-nen with -nen for the expected -g an ending. Thus, -nen signals not just ‘3sg object’ but also ‘3sg subject.’ For 3pl objects (‘left them’) we have the forms t -pela-nat ‘I left them,’ m t-pela-nat ‘we left them,’ pela-nat ‘you (sg.) he left them,’ na-pela-nat ‘they left them,’ showing that -nat means ‘them.’ But again the 3sg subject form has a different suffix: pelanenat ‘he left them.’ Thus, -nenat means both 3sg subject and 3pl object. The forms pela-tk introduces further deviations from agglutination. When we consider the other five tense forms and the imperative and conditional paradigms we often find that the subject/object endings display additional differences. This shows that those endings simultaneously signal information (in part) about the tense and mood of the verb, as well as the person/number of the subject and object. Complexities such as these are the rule rather than the exception with morphologically rich languages, even those often vaunted as highly regular or agglutinating such as Turkish or Hungarian.

A further complication arises from the forms enapela-g e ‘you (sg.)/he left me,’ ena-pela-t k ‘you (pl.) left me’ and pela-tko-g e ‘you (sg.) left us,’ pela-tko-t k ‘you (pl.) left us.’ The suffixes here are not in fact normal realizations of the first person object (these are -g m and m k for singular and plural respectively as seen in the forms na-, pela-g m, na-pela-m k ‘they left me/us’). Rather, these endings are borrowed from intransitive verbs. It turns out that these forms are identical to forms of two special voice forms, the antipassive, in which a transitive verb is conjugated as though it were intransitive. The two antipassives are signalled by the prefix enaand the suffix -tko. As an antipassive form ena-pela-g e would mean something like ‘you/he were engaged in the process of leaving (someone/something or other).’ However, the form has been co-opted for use as a transitive verb form in a systematic fashion. It is quite common in morpho- logically complex languages for one part of a paradigm to be ‘borrowed’ by another part, supplanting the forms one might otherwise expect (syncretism). It is particularly difficult to describe syncretism using the morpheme concept, because we would have to provide affixes such as ena-, -tko with artificial ‘meanings’ such as ‘first person object,’ when in fact their use is entirely different. It is simply impossible to state the Chukchee syncretism in morphemic terms, and thus it is impossible to state the essential generalization in a morphemic theory.

Complications such as these have encouraged many morphologists to abandon the morpheme concept, at least for inflection, and adopt the lexeme concept. Inflectional paradigms are treated as the result applying sets of rules or principles which state the way a given form is related to other forms. Thus, each word form is associated with the set of features which characterize its position in the paradigm of forms. In the very simple case of English nouns we say that there is a feature [NUMBER] with the values [NUMBER: Singular], [NUMBER: Plural]. The feature [NUMBER:Plural] triggers the -z affixation process (or the man-to-men alternation or whatever). We say then that the -z affix realizes, or is an exponent of, that feature. There is no sign ‘plural’ which is combined with the sign for ‘dog.’ To handle the Chukchee case we write a battery of rules which are triggered by morphological features such as [Subject = 3sg, Object = 3pl]. These then add the various affixes according to the principle that the most specific rule applies first. Thus, there is a rule governing 3sg Subject/3pl Object which states ‘add -nenat,’ and this is more specific than the general (default) rule governing 3pl Object which says ‘add -nat.’ Similarly, in English the plural form for words such as man is specified in lexical entries for those words, and this specification overrides the default, Theories which reject the morpheme concept in this way will be called ‘realizational’ theories.

Rules systems such as these can easily handle many of the problems posed by zero morphemes. Thus, to represent the fact that the word form dog ‘means’ dog- in-the-singular, we just assume a general default rule for English which states ‘for any noun the value of [NUMBER] is [NUMBER: Singular].’ This default rule will always be more general than even the regular plural rule, and so it will only apply to those noun word forms which are not marked [NUMBER: Plural]. Thus, we can readily specify the feature value of singular ‘dog’ without resort to suspicious null entities. Likewise, syncretisms can be handled by special ‘rules of referral’ which would state that the Chukchee second person subject–first person object forms are ‘referred’ to the corresponding parts of the enaantipassive paradigm.

6. Productivity And Regularity

There are various suffixes in English which create deadjectival property nominalizations, that is, nouns derived from adjectives meaning ‘property of being Adjecti e,’ including: -th (warmth, strength), -ity (readability, curiosity, piety), -ness (goodness). These differ in important respects. The -th suffix is no longer used to form new words; the -ity suffix is restricted essentially to words derived from Latin, while the -ness suffix is used for all those words which do not take suffixes such as -th or -ity. In some cases, -ness is more or less acceptable even with words which by rights should take a different ending (thus warmness, piousness are relatively acceptable). In addition, -th and -ity may induce irregular phonological changes in the stem (strong → strength; curious → curiosity), while this is never true of -ness.

It would appear that -ness is the productive suffix in the sense that there is some guarantee that it can be used for new words, whereas this guarantee is lacking in the case of -th, -ity. Thus, if a speaker uses (or coins) a new adjective, say, nerdy, then-ness will be the suffix used to create the nominalization: nerdiness. However, it turns out to be very difficult to pin down a watertight notion of productivity, largely because it is very unclear how to measure it. The productivity of an affix or morphological operation depends on the number of bases to which it could attach. Thus, there is a suffix l et in Chukchee which attaches to nouns such as ‘dog’ or ‘boat’ and means ‘to travel by means of Noun.’ Within the limitations imposed by this meaning the suffix appears to be completely productive even though it only gives rise to a limited number of lexemes. In other cases it is not even quite clear what constitutes a base. Thus, a -th suffix (distinct from the nominalizing -th) attaches to numerals greater than ‘three’ to form ordinals: fifth, nineteenth. But how many such bases are there? Does ‘four thousand three hundred and nineteen’ constitute a base distinct from ‘nineteen’? A further interesting complexity is illustrated by -ity. This suffix regularly attaches to adjectives which themselves have been formed from a verb by the suffix -able ‘such that can be Verb-ed,’ e.g., washable. For this class of adjectives, -ity suffixation seems to be almost totally productive, a situation sometimes known as ‘relative productivity.’

We may also ask what constitutes the data over which such calculations should be based. For some (written) languages there are very large grammatically analyzed corpora of several million words which allow us to determine how often a particular affix is used. One measure of productivity based on such corpora (developed by Harald Baayen 1991) calculates an index based on the number of new words in the corpus with that affix which only occur once in the entire corpus (‘hapax legomenon’). The idea is that a word of such rarity is almost certain to have been created newly by the writer/speaker, so the more such unique words we find with a given affix, the more it would seem that the affix is being used productively. In practice this method provides a useful measure, though it is dependent on the size of the corpus (a small corpus or one which was not sufficiently representative would give misleading results). However, counting words in a corpus is not an ideal procedure because it only indirectly tells us about the grammatical systems which speakers use. Indeed, it is perfectly possible that some morphological operations show different degrees of productivity for different speakers.

Recent psycholinguistic evidence bears on this problem in interesting ways. Subjects can be asked to perform a variety of psycholinguistic tasks on morphologically complex words, such as distinguishing real words from nonsense words as quickly as possible. In some cases the subjects’ responses are dependent on the frequency of the target word, on how many other words are similar to it (e.g., how many words rhyme with it) and so on. Such words tend to be those with unproductive, irregular morphology, such as sang, written. In the case of regular words (such as walked ), the response pattern is relatively independent of such factors. Some psycholinguists argue that this points to a dual mechanism for processing complex words (see Pinker 1991). The irregular formations are simply stored in memory, which renders them susceptible to the phenomena known to affect the operation of memory, such as frequency of occurrence and analogy with similar forms. The regular formations are created by linguistic (symbolic) rule systems, which are independent of such memory factors. This is a controversial approach to morphology, but it furnishes a different way of looking at the problem of productivity, namely, in terms of regularity, as determined by linguistic analysis and confirmed (or sometimes disconfirmed!) by psycholinguistic testing.

In a realizational model ‘productivity’ is to be equated with ‘regularity.’ Thus, the -ness suffix is productive precisely because it is the default affix for de-adjectival property nominalizations. This default realization can be overridden by more specific lexical representations such as that for warmth. However, realizational theories also make use of the notion of the ‘nested default.’ For adjectives ending in -able the default nominal suffix is -ity, not -ness. This is a more specific principle than -ness suffixation because it is restricted to -able adjectives, but it is not (necessarily) a fact which has to be stated for all -able adjectives individually. Thus, in principle it can be stated as a linguistic rule, like -ness affixation, but of a more restricted kind. A currently open question, which is the subject of ongoing psycholinguistic research, is whether such ‘specific’ or ‘nested defaults’ are treated as regular morphology like -ness affixation or as irregularities which are simply memorized on a case by case basis, like -th.

7. Evidence For A Distinct Morphology Component

An important theoretical question in general linguistics is the existence of separate modules of the language faculty with their own properties. Minimally, it would seem that there have to be two modules, a sound module interfacing with speech production and comprehension, and a meaning module interfacing with the conceptual system. Chomsky’s (1995) Minimalist Programme explores the idea that only these two interfaces are of significance for the architecture of the language faculty and that the ‘computational system’ is limited to syntax. However, it is apparent that there are principles of organization governing words which are independent of syntax. One clear case is the existence of inflectional classes.

In addition to inflecting for case number, Russian nouns must belong to one of three genders, masculine, feminine, or neuter (gender is defined in terms of the syntactic phenomenon of agreement, see Syntax). The endings which a noun takes depend on the lexically specified inflectional class (declension) to which it belongs. A fragment of the system is given in Table 2.

Inflectional class and gender class are related but are not identical. Ignoring lexically specified exceptions in some of the classes, we can predict the default gender for each class, as shown in Table 2. However, both Class II and Class III contain feminine nouns, which means that it is not possible to predict inflectional class from gender specification (in general, both inflectional class and gender class are arbitrary properties of a lexical item).

The point about these examples is that Russian nouns are organized according to inflectional classes independently of phonology, syntax, or semantics. They are an instance of what Aronoff (1994) calls ‘morphology-by-itself.’ It is an important question whether such purely morphological classes are learnt, organized, and processed according to specifically linguistic principles, distinct from the principles governing other cognitive capacities. If this proves to be the case, then we will have an important deviation from Chomsky’s ‘Minimalist’ framework, in that such organization is not determined by the requirements of the interface with sound and meaning. On the other hand, if inflectional class organization can be shown to obey principles of associative memory, like irregular past tenses in English then it may be that there is no specifically linguistic morphological module.

Bibliography:

- Aronoff M 1994 Morphology By Itself. MIT, Cambridge, MA

- Baayen R H 1991 Quantitative aspects of morphological productivity. In: Booij G, van Marle J (eds.) Yearbook of Morphology 1991. Kluwer Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 109–49

- Carstairs-McCarthy A 1992 Current Morphology. Routledge, London

- Chomsky N 1995 The Minimalist Program. MIT, Cambridge, MA

- Matthews P 1991 Morphology, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Pinker S 1991 Rules of language. Science 253: 530–5

- Spencer A 1991 Morphological Theory. Blackwell, Oxford

- Spencer A 2000 Morphology. In: Aronoff M, Rees-Miller J (eds.) Handbook of Linguistics. Blackwell, Oxford

- Spencer A, Zwicky A (eds.) 1998 Handbook of Morphology. Blackwell, Oxford.