Sample Comparative Method in Linguistics Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The comparative method is the most important of the various techniques used to recover linguistic history. It is a method (or a set of procedures) which compares related languages, descendants from a common ancestral language, in order to postulate, to ‘reconstruct,’ the ancestral language. It is commonly considered a major event in the history of ideas; inspired by the success of the comparative method in linguistics, numerous other disciplines in the nineteenth century adopted comparative methods of their own. In this research paper the comparative method is explained and its basic assumptions and limitations are considered.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Comparative Method And Language Families

Language which belong to the same family are said to be genetically related—this means that they derive from a single ancestral language, called a protolanguage. Genetic relationships among languages are talked about in genealogical terms: ‘sister languages,’ ‘daughter languages,’ ‘parent language,’ and ‘language families’ (definitions below). Through linguistic changes, dialects develop in a language, and then as further changes accumulate in time, these dialects become distinct languages, related to one another (‘sister languages’) and descendants (‘daughters’) of the original language (the parent or proto-language). By applying the comparative method to related languages which descend from an original ancestor language, linguists postulate what that proto-language was like—that is, they reconstruct that language. For example, a comparison of English with its relatives, Dutch, German, Danish, Swedish, Icelandic, and so on, reveals what the proto-language, in this case called ‘Proto-Germanic,’ was like. Thus, English is, in effect, a much changed ‘dialect’ of Proto-Germanic, having undergone successive linguistic changes to make it what it is today, a different language from Swedish and German and its other sisters, each of which underwent different changes of their own. Therefore, every proto-language was once a real language regardless of whether it is successfully reconstructed or not, and all languages which have relatives have a history which classifies them in language families.

The aim of the comparative method is to reconstruct as much as possible of the proto-language by comparing its daughter languages (the related descendant languages), and to determine what changes they underwent as they diversified from their common ancestor. The comparative method serves two purposes: to show that languages are related, and to reconstruct as much as possible of the parent language. If reconstruction is successful, it shows that the initial assumption that the languages are related was warranted, and it reveals the nature of the proto-language.

Of course, success is dependent upon the extent to which evidence of the original traits is preserved in the descendant (daughter) languages and upon how astute the linguist is at applying the comparative method to them. For example, by comparing Romance languages (Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, etc.), the linguist reconstructs Proto-Romance; Proto-Romance is equivalent to the spoken language at the time Latin began to split up into its descendants. If successful, what is reconstructed for Proto-Romance by the comparative method should coincide with the ProtoRomance which was actually spoken at the time before it split up into its daughter languages. In this case, since Latin is abundantly documented, it is possible to check to see whether what is reconstructed by the comparative method accurately approximates the spoken Latin that is known from written sources at that time. However, the possibility of checking reconstructions in this way is not available for most language families, for whose proto-languages there are no written records. For example, for ProtoGermanic (from which English, German, Swedish, etc. descend), there are no written records, and this language is known only from comparative reconstruction.

Often attempts to show that languages are genetically related or to reconstruct a proto-language begin with recognition of similarities among the languages being compared. However, similarities among languages can be due to a number of things, for example to borrowing, accident, onomatopoeia, etc., in addition to inheritance from a common ancestor (see Campbell 1998, pp. 311–26). Therefore, to show languages are related or to reconstruct successfully, similarities which are explained by factors other than common inheritance need to be avoided. The comparative method, aided by regular sound correspondences, helps to eliminate these factors.

2. Application Of The Comparative Method

To be able to apply the comparative method, one needs to know some technical terms.

Proto-language. (a) The once spoken ancestral language from which daughter languages descend; (b) the language reconstructed by the comparative method which represents the ancestral language from which the compared languages descend. (To the extent that the reconstruction is accurate and complete, (a) and (b) should match.)

Sister language. Languages which are related to one another by virtue of having descended from the same common ancestor (proto-language) are sisters; that is, languages which belong to the same family are sisters to one another.

Cognate. A word which is related to a word in sister languages by reason of these forms having been inherited by these sister languages from a common word of the proto-language from which the sister languages descend.

Cognate set. The set of words which are related to one another in the sister languages because they are inherited and descend from a single word of the protolanguage.

Sound correspondence. In effect, a set of ‘cognate’ sounds; the sounds found in the related words of cognate sets which correspond among related languages because they descend from a common ancestral sound. (A sound correspondence is assumed to recur in various cognate sets.)

Reflex. The descendant in a daughter language of a sound of the proto is said to be a reflex of that original sound; the original sound of the proto-language is said to be reflected by the sound which descends from it in a daughter language. (Cf. Campbell 1998, p. 112.)

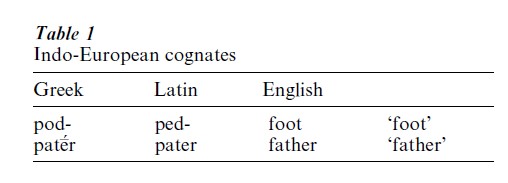

In the application of the comparative method, first potential cognates among related languages (or among languages for which there is reason to suspect relatedness) are sought. It is convenient to begin with cognates from ‘basic vocabulary’ (body parts, close kinship terms, low numbers, common geographical terms), since these tend not to be borrowed from other languages. Ultimately, it is the systematic sound correspondences discovered in the application of the comparative method which demonstrate which are true cognates. Words which are similar due to accident, borrowing, and other non-genetic factors usually do not exhibit the recurring sound correspondences that true cognates do. Some cognates from Greek, Latin, and English (members of the Indo-European family of languages) are illustrated in Table 1.

Next, the sound correspondences are sought. For example, in the cognates of Table 1, the first sound in each of the cognate sets exhibits the sound correspondence

Greek p, Latin p, English f

Since the sound correspondence recurs in these (and many other) cognate sets, it is unlikely that it could come about by sheer accident.

When the sound correspondences have been determined, the next step is to reconstruct the original sound. Linguists postulate what the original sound in the proto-language most likely was based on the phonetic properties of the sounds in the daughter languages as represented in the sound correspondence set. General guidelines help determine the most realistic reconstruction. For one, the known direction of certain sound changes is a valuable clue. For example, many languages have changed p to f, but change in the other direction, f to p, is extremely rare. In this case, it is said that the expected direction is p to f (and not f to p). This being the case, for the sound correspondence of Greek p-, Latin p-, English f-, *p is reconstructed, since a change *p to f, which would be necessary to derive the English reflex of f, is in an expected direction. (Note that the asterisk, as here with *p, symbolizes reconstructed things.) If *f were postulated for the proto-sound from which this sound correspondence descended, it would be necessary to assume the change of *f to p in Greek and Latin, a change which goes against the expected directionality. Therefore, *p is reconstructed in this case, together with the assumption that English underwent the common sound change of *p to f.

Another guideline is the principle of ‘majority wins’: unless there is evidence to the contrary, for the protosound one reconstructs a sound coinciding with the particular sound in the correspondence set which is found in the greatest number of daughter languages. In this example, since p is found in both Greek and Latin, but f is only in English, ‘majority wins’ selects *p for the reconstruction. Common sense is behind this; it is less likely that the same change (here *f to p) would take place independently several times (here in Greek and in Latin) than that a single change would take place only once (*p to f, only in English). The interpretation of the majority, however, can be complicated, requiring caution in the application of ‘majority wins.’

This process of reconstructing sounds for the various correspondence sets is repeated until all the sounds of the proto-language have been reconstructed and the changes in the daughter languages worked out.

When all the proto-sounds have been reconstructed, it is possible to reconstruct words of the protolanguage. For example, in the cognate set Greek pod, Latin ped, English foot ‘foot,’ *p has already been reconstructed as the first sound of this word in the proto-language, based on the p-, p-, fcorrespondence set just considered. For the second sound (o, e, oo), *e is reconstructed on evidence not available in this short example; the correspondences for the vowel are complicated. For the last sound of the word, evidence from other cognate sets shows that the sound correspondence, Greek d, Latin d, English t, recurs and that the best reconstruction for this sound is *t. Putting these reconstructed sounds together, *p for the first sound, *e for the second, and *d for the third, gives the reconstruction *ped ‘foot,’ a word in the protolanguage. In this way the vocabulary of the protolanguage can be recovered.

The reconstruction of a sound, a word, or large portions of a proto-language is, in effect, a hypothesis (actually a set of interconnected hypotheses) concerning what those aspects of the proto-language must have been like. Hypothesized reconstructions can be tested; sometimes they prove wrong; sometimes they must be modified, based on new insights. These insights may involve new interpretations of the data already on hand/or new information that may come to light. The discovery of a previously unknown language may provide new evidence, a different testimony of the historical events which transpired between the protolanguage and its descendants, which can change how parts of the proto-language are viewed. For example, with the discovery and decipherment of Hittite (and other languages of the Anatolian branch of IndoEuropean), the whole picture of Proto-Indo-European phonology changed.

There are numerous general treatments of the comparative method; for some of the clearer accounts, see Anttila (1989), Arlotto (1981), Campbell (1998), Crowley (1997), Hock and Joseph (1996), and Trask (1996).

3. Assumptions And Limitations Of The Comparative Method

There are limitations on what can be recovered of a proto-language via the comparative method. Traditionally, some of these limitations are called ‘assumptions,’ since they are inherent consequences of how the comparative method is structured and how it is applied.

There are four main ‘assumptions.’

(a) The proto-language was uniform, with no dialects or variation.

Clearly this ‘assumption’ is unrealistic, since all known languages have regional or social variation, different styles, and so on. However, it is not so much that the comparative method ‘assumes’ no variation; rather, it is just that there is nothing built into the comparative method which would allow it to address variation directly. This means that what is reconstructed will not recover the once spoken protolanguage in its entirety, that is, with all its variation. Still, rather than stressing what is missing, linguists are happy that the method provides the means for recovering as much of the original language as it does. This assumption of uniformity is a reasonable idealization; it does no more damage to understanding of the proto-language than, say, modern reference grammars do which concentrate on a language’s general structure, typically leaving out consideration of regional, social, and stylistic variation. Moreover, dialectal variation is not always left out, since in some cases scholars do reconstruct dialect differences to the protolanguage based on differences in daughter languages which are not easily reconciled with a single uniform starting point.

Assumptions (b) and (c) are related:

(b) Language splits are sudden.

(c) After the split up of the proto-language, there is no subsequent contact among the related languages.

These assumptions are a consequence of the fact that the comparative method addresses directly only material in the related languages which is inherited from the proto-language and has no means of its own for dealing with borrowings, the results of subsequent contact after diversification into related languages. Borrowing and the effects of language contact are, however, not neglected. Rather, it is necessary to call upon other techniques which are not formally part of the comparative method for dealing with borrowing and the results of language contact. It is true that the comparative method contains no means for addressing whether a language gradually diverged over a long period of time before ultimately distinct but related languages emerged, or whether a sudden division took place with no subsequent contact between the parts of the original language community. Usually, however, reconstruction by the comparative method is reasonably successful, regardless of how slow or sudden the split up of the proto-language may have been.

(d) Sound change is regular.

This assumption is true; it is not a limitation, but an asset, extremely valuable to the application of the comparative method. For example, in the example above, Proto-Indo-European *p regularly changed to f in English in all the words of this kind which formerly contained a *p. Knowing that a given sound in given circumstances changes in a regular fashion permits reconstruction of what the sound was like in the parent language. If a sound could change in arbitrary, unpredictable ways, it would not be possible to determine from a given sound in a daughter language what it may have been in the parent language, and, for a particular sound of the parent language, it would not be possible to determine what its reflexes in its daughter languages would be. If, for example, an original *p of the proto-language could arbitrarily for no predictable reason become f in some words, y in others, k in still others, and so on, then it would not be possible to reconstruct it. In such a situation, comparing, say a p of one language with a p of another related language would be of no avail, if the p in each could have come in unpredictable ways from a number of different proto-sounds.

4. How Realistic Are Reconstructed Proto-Languages?

The success of any given reconstruction depends on the material at hand with which to work, and the ability of the comparative linguist to figure out what happened in the history of the languages being compared. In cases where the daughter languages preserve clear evidence of what the parent language had, a reconstruction can be very successful, matching closely the actual spoken ancestral language from which the compared daughters descend. However, there are many cases in which all the daughter languages lose formerly contrasting sounds and lose grammatical categories through changes of various sorts. It is not possible to recover via the comparative method things in the proto-language if the daughters simply do not preserve evidence of them. In cases where the evidence is severely limited or unclear, reconstruction often results in omissions or mistakes. The comparative linguist makes the best inferences possible, based on the evidence available and on everything known about the nature of human languages and linguistic change. It is necessary to make the most of what is available to work with. Often the results are very good; sometimes they are incomplete, occasionally wrong. In general, the longer in the past the proto-language split up and the more linguistic changes that have taken place in the daughter languages, the more difficult it becomes to reconstruct with full success.

A comparison of reconstructed Proto-Romance with attested Latin provides a telling example. It is possible successfully to recover a great deal of formerly spoken Proto-Romance via the comparative method. However, the modern Romance languages for the most part preserve little of the former noun cases and complex verb inflections which Latin had. Subsequent changes have obscured these aspects of the grammar so much that large parts of Proto-Romance are not reconstructible by the comparative method. On the other hand, a great deal of Proto-Romance is recoverable.

An area of speculation and controversy concerns the outer limits of the comparative method. That is, is there a recognizable time depth beyond which the comparative method ceases to be effective? Some suggest that the comparative method cannot reach beyond the oldest currently reconstructed protolanguages; this cut-off date beyond which the comparative method is assumed not to be able to reach is variously speculated to be 6000, 8000, or 10,000 years. Since there is no reliable means of dating languages splits, these dates are rough guesses. The true issue is not really about dates at all, but rather about how much evidence related languages preserve upon which to base a reliable reconstruction. Typically, languages separated by many millennia have had longer in which to undergo changes, making them more different from one another than languages separated only by a few hundred years. Languages which have undergone many changes conceivably could preserve little of their original vocabulary or grammar; however, at the same time, it is also possible for a language to undergo relatively little change over relatively long periods. Thus, the upper limit of the comparative method is a function of whether accumulated changes have obliterated evidence in related languages, and not directly a matter of how long they have been separated.

Bibliography:

- Anttila R 1989 Introduction to Historical and Comparati e Linguistics, 2nd, rev. edn. Benjamins, Amsterdam

- Arlotto A 1981 Introduction to Historical Linguistics. University Press of America, Washington, DC

- Campbell L 1998 Historical Linguistics. MIT, Cambridge, MA

- Crowley T 1997 An Introduction to Historical Linguistics, 3rd Oxford University Press, Auckland

- Hock H H, Joseph B D 1996 Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship: An Introduction to Historical and Comparative Linguistics. Mouton, Berlin

- Trask R L 1996 Historical Linguistics. Arnold, London