Sample Movement Theory And Constraints In Syntax Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Movement in Syntactic Theory

Movement theory is a ‘trademark’ of Generative Transformational Grammar. In this line of inquiry, certain sentences are generated, not just by combining words or phrases in some appropriate order, but also by moving them from one position to another. Thus the sentences (1)–(3) below are not constructed by directly ‘merging’ the leading items will, what, and John respectively at the sentence-initial position, but by first introducing them in their ‘original’ positions (marked by the underscores) and then moving them to the initial position:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

(1) Will John ___ buy this toy?

(2) What has John put ___ on the table?

(3) John was arrested ____ yesterday.

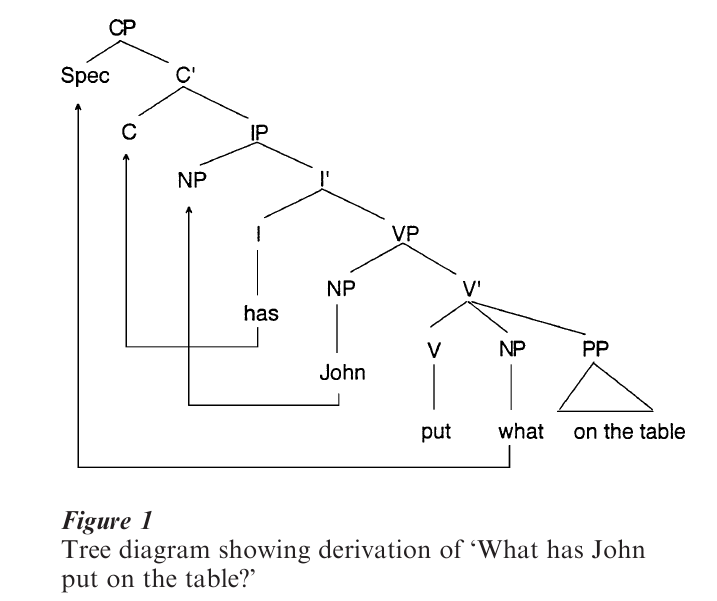

In the Principles and Parameters Theory as implemented in the Government-Binding-Barriers framework (Chomsky 1981, 1986), the computation system of a grammar generates underlying Deep- Structure (DS) representations in accordance with the X´Theory that satisfy the selectional requirements of lexical items, and transformational operations (particularly, movement operations) convert them to Surface-Structure (SS) representations. These SS representations are in turn mapped onto two levels that form the interface between grammar and other cognitive performance systems, PF (Phonetic Form) on the one hand and LF (Logical Form) on the other. Thus, for sentence (2) above, the computation system will carry out movement operations (as indicated by the arrows) that turn its DS to its SS representation:

It is assumed that the mapping SS → PF, and especially SS → LF, also involve critical movement operations.

2. Motivations For Movement

In some cases the postulation of movement can be justified by intuitive observations. The verbs put and arrest are transitive in traditional terms, requiring NP objects following them (compare, for example *John put on the table; *Bill arrested; an asterisk preceding a sentence indicates ungrammaticality). In sentences (2) and (3), no NP object appears in the ‘expected’ postverbal position, despite their grammaticality. This paradox is explained if one says that put does have a postverbal object at DS, though the object is fronted at SS (as depicted in Fig. 1). The postulation of movement thus enables one to preserve generalizations about the predicate-argument structure of verbs and other lexical items that explain grammatical well-formedness.

In other cases, the movement hypothesis has enabled generative syntacticians to unearth interesting phenomena that had escaped introspection in previous descriptions, and gain valuable insight into syntactic structure. For example, it is now widely assumed that, despite their surface similarity, derivation of sentence (4a), but not of (4b), involves movement:

(4) a. Harry seems to be honest.

- Harry tried to be honest.

In particular, in (4a) but not (4b), the subject of the main verb seem originates as the subject of be honest and raises to the higher subject position at SS. Postulating Subject Raising in (4a) but not (4b) explains several differences between seem-type and try-type sentences that surface upon closer examination, including e.g., The shit seems to be about to hit the fan (under the idiomatic interpretation) but *The shit tries to be about to hit the fan, etc. Similarly interesting facts have been explained concerning Mary is likely to lea e vs. Mary is eager to lea e vs. Mary is easy to lea e.

In yet other cases, the existence of movement could not have been detected by intuitive observations of the type one can make concerning sentences (1)–(3). One early rule, proposed by Chomsky (1955) and popularly known as Affix Hopping, concerned tense marking in English finite sentences. The fact is that tense marking seems to ‘migrate’ among auxiliary elements and the main verb: it may occur on a modal (Monica would sing, but *Monica will sang), on a perfective or progressive aspect (Monica has sung, Monica is singing, but *Monica ha e sings, *Monica ha e is singing, etc.), or directly on the main verb (Monica sang). A context free phrase-structure grammar would be hard put to describe this range of sentences in any simple way. Chomsky proposed treating the tense inflectional suffix as an independent syntactic item in DS representation (as a leftmost constituent of the Auxiliary) which, by Affix Hopping, ‘docks’ on whatever first auxiliary or verbal element follows it. Affix Hopping vastly simplifies the grammar of tense-marking, at the same time capturing the observed ‘migration’ (hopping) property insightfully.

The primary argument for movement is that it allows one to simplify grammatical descriptions, capture significant generalizations, and uncover deep insight into the nature of human language as a ‘mirror of the mind.’ Such considerations justify the movement hypothesis not only for more observable cases like sentences (1)–(3) and (4a), but also many surprising or less observable cases. (Some versions of generative syntax incorporate other devices to explain the ‘movement phenomena,’ including Lexical Functional Grammar, head-driven phrase structure grammar, categorical grammar, Dependency Grammar.)

3. Evolution Of Movement Theory

3.1 Early Movement Theory

The early years following Chomsky’s proposal of Affix Hopping saw an entire field of syntax scholars devoted to grammatical description applying the transformational model. New syntactic phenomena were unearthed or became interesting enough theoretically to call for an analysis, and new rules were added to the repertoire of a grammar’s transformational component. In addition to Subject-Auxiliary Inversion, Wh-Movement, Passivization and Subject-Raising illustrated in sentences (1)–(3) and (4a) respectively, and the aforementioned Affix Hopping, other movement rules were also proposed, including Relativization (as shown in sentence (5)), Topicalization (6), ToughMovement (7), Extraposition from NP (8), etc.

(5) This is the person who I have always wanted to meet ___.

(6) This sort of movie, I would never watch ____.

(7) John is tough for us to deal with ____.

(8) A book has just appeared on syntactic theory.

In order to ensure descriptive adequacy, each rule proposed was formulated in such a way as to (a) apply to only the input strings that meet a certain Structural Description (SD), (b) effect precisely the Structural Change (SC) as desired, and (c) only do so under any additional conditions as may be imposed. Thus the Passivization rule of English was defined in terms of the SD of an input structure that contains a postverbal object NP and the instruction for SC that it will (among other things) front the NP to the subject position. Additional conditions are noted for the applicability of the rule, among them the requirements that the main verb be put in the passive participle form, that the movement be carried out to an immediate local subject position, etc. Other rules were defined with similar explicitness and in detail. Because the investigations were carried out in the generative (i.e., formal) approach, linguists working on syntactic phenomena were required to formulate precise hypotheses about the form and functioning of movement transformations they proposed. The explicit (and therefore falsifiable) formulations led to unprecedented expansion of our explicit knowledge of natural language syntax.

3.2 Modularity: From Rules To Principles

While the detailed formulations of movement rules helped ensure observational and descriptive adequacy of proposed grammatical descriptions, linguists realized increasingly that the adequacy was achieved at the cost of explanatory adequacy and conceptual beauty. For one thing, the detailed statement for each movement rule obscured the fact that many movement rules have similar properties. By stipulating these properties repeatedly in the statement of every rule, the theory was highly uneconomical and failed to capture the generality of such properties. In fact, some properties often included in the statement of movement rules are not peculiar to movement, but hold generally of other syntactic phenomena as well. To capture the correct generalizations, then, it was necessary to separate out general properties from the statement of specific rules.

One general property of movement that was repeatedly stipulated in the formulation of each rule is that movement is generally upward, i.e., that it moves elements to a ‘c-commanding’ position. Defined in terms of tree diagrams like Fig. 1, a node α ccommands β iff neither α nor β dominates (contains) the other, and the first branching node dominating α dominates β. In Fig. 1, each instance of movement is upward to a position c-commanding the original position. This ‘upward movement requirement’ should be stated once and for all movement rules, rather than separately for each rule. In fact, Chomsky (1975) noted that this requirement is just a special case of a more general principle that also governs anaphora in natural language. For example, the interpretation of a reflexive pronoun in English requires that it have an antecedent that c-commands it: John criticized himself, but *John’s mother criticized himself (the latter is ungrammatical because the intended antecedent John is not high enough to c-command himself ). To capture this common property between movement and anaphora, Chomsky proposed that, when a category is moved, it leaves a ‘trace’ behind, co-indexed with the moved category (as in Johni was arrested ti yesterday for sentence (3)). The trace, being phonetically empty and having no inherent reference, depends on the moved category as its ‘antecedent,’ much as a reflexive depends on another noun phrase for its reference. The ‘upward movement requirement’ thus reduces to a general requirement governing anaphoric dependency, and may be eliminated from the statement of each movement rule.

Another common property of movement rules is that they operate only locally, as the next section will show. A third general property is that movement seems to operate in a structure-preserving manner, so that a head (e.g., verb) can only move to a head position, an argument NP to an argument position (Aposition), and an operator to an operator position (A -position). (See again Fig. 1, illustrating has undergoing head-movement, John undergoing A-movement, and what undergoing A -movement.) The discovery of these and other general properties finally led linguists to the view that most details formerly attributed to individual rules should be dissociated from them and be ascribed to independent modules of grammar each with general applicability, and that all movement rules can be reduced to one rule of maximal simplicity: Move α, α a category. The result is a highly modular theory of movement: Universal Grammar consists of only one general movement rule, Move α, and a number of independent general principles whose interaction among themselves and with Move α produce a complex array of syntactic phenomena. There is then no Passivization or Relativization as a movement rule per se, these being simply special instances of Move α. This modular view of grammar culminated in the theory of Government and Binding in Chomsky (1981) and subsequent works, and is still the prevalent view of current researchers in generative grammar.

Under this highly modular view of movement, there is little or nothing left to do in the formulation of the movement rule itself. At the same time, increasing attention has shifted to the study of other modules of grammar, in particular the study of general locality constraints on movement, and on the distribution of empty categories created by movement.

4. Constraints on Movement

In generative linguistics, a grammar G of a given language L is a hypothesis about the linguistic phenotype of the speakers of L. Such a hypothesis is descriptively adequate only if it defines all and only the (potential and actual) grammatical sentences of the language. A linguistic theory, a hypothesis of the human linguistic genotype, is likewise adequate only if it defines all and only the possible grammars that are descriptively adequate. In the early stages of generative grammar study, linguists were occupied primarily with providing their grammars with enough descriptive powers to generate all grammatical sentences. In most subsequent developments to date, however, most attention has been directed toward restricting the expressive powers of their grammars. The study of movement constraints was motivated not only on empirical grounds of descriptive and explanatory adequacy, but also because it has proven a very productive probe into the nature of the human language faculty.

4.1 A-Over-A And Ross Constraints

The need for a general, powerful constraint on movement rules was noted quite early by Chomsky (1964), who proposed the A-over-A Principle to exclude movement of a phrase out of a larger phrase of the same type. The importance of movement constraints gained widespread attention with the emergence of Ross (1967), who showed the A-over-A to be inadequate and proposed, in its place, a module of grammar containing a set of ‘island constraints.’ According to Ross, although movement rules may appear to displace constituents over an arbitrary distance (e.g., Whati did Harry say that Maria bought ti?), they must be constrained sharply so as not to extract elements out of certain domains that he called ‘islands.’ The following examples (sentences (9)–(14)) respectively) illustrate Ross’s island constraints (in each case the relevant ‘island’ is marked by square brackets): Coordinate Structure Constraint (CSC), Complex NP Constraint (CNPC), Sentential Subject Condition (SSC). Other familiar constraints include the Subject Condition (SC), the Adjunct Condition (AC), and the Wh-Island Condition (WIC):

(9) * Whati did [Harry buy ti and Maria buy a pencil]? (CSC)

(10) * Whati did Harry talk to [the woman who bought ti]? (CNPC)

(11) * Whati was [that Maria had bought ti] surprising? (SSC)

(12) * Whoi did [a picture to ti] please you? (SC)

(13) ?* Whati did Harry go home [before Maria bought ti]? (AC)

(14) ?* Whati did Harry wonder [who bought ti]? (WIC)

4.2 Subjacency, CED, And The ECP

The Ross-style constraints effectively reduced the power of grammar but, as given, they amounted to a list of environments that form ‘islands’ to the exclusion of those that do not, and thus failed to explain their clustering. Chomsky (1973) proposed subsuming most of Ross’s island constraints under one general Subjacency Condition, which prohibits extraction of a constituent across two or more ‘bounding nodes’ (NP or S). Huang (1982) argued that the SSC/SC and AC reflect a general complement vs. non-complement asymmetry and are best collapsed under one general Conditon on Extraction Domains (CED), which provides that extraction is possible only from ‘properly governed’ domains (i.e., complements). (See also Kayne 1981.) The notion of proper government also plays a crucial role in defining the Empty Category Principle (ECP), which excludes long extraction of a subject or an adjunct, as shown in sentences (15)–(16):

(15) * This is the person whoi John wondered

[whether ti would fix the car].

(16) * This is howi John wondered [whether Bill

would fix the car ti].

The ECP requires that each trace be governed by a lexical head, or extraction must be local (short distance). Long extraction is excluded in sentences (15) and (16) because subjects and adjuncts are not governed by a lexical head.

4.3 Barriers, Economy, And Minimalism

The program of unifying (and thus explaining) movement constraints continued in Chomsky (1986), where a single notion of barrierhood was proposed to tie together these conditions, whereby the theory of bounding (Subjacency and CED) allows movement to cross at most one barrier (at a time), and the theory of government (ECP) requires that a trace not be separated from its governor by any barrier at all. The barriers framework also provided a tool for measuring the degree of (un)grammaticality in incremental terms, capturing the fact that a movement crossing n barriers produces worse results than one that crosses n 1 barriers. The various constraints, defined in terms of barrierhood, then reduce to the notion that grammars select movements that are local, or as local as possible.

The notion of locality led to the idea of minimality and economy. Rizzi (1990) argued that most of the locality constraints can be reduced to the proposal that each movement operation must land at the closest potential landing site. The general success of reducing movement constraints to minimality is an important step that led Chomsky to other considerations of economy (minimality being one type of economy) and to the design of the Minimalist Program, which aims to employ no theoretical apparatus or levels of representation beyond ‘virtual conceptual necessity,’ and only derivations that occur with ‘least effort’ or as a ‘last resort.’ In Chomsky (1995), minimality is incorporated directly into the definition of Attract F, a reformulation of Move α.

Although the early A-over-A Principle proved to be inadequate as a unifying general constraint on movement, the various constraints are unified finally under one notion, this time couched in a general theory of economy.

5. Covert Movement: The Syntax Of LF

In the Principles and Parameters theory, it is assumed that movement may be overt (if it occurs before SS—or Spell-Out), or it may be covert (if it occurs in LF). In the examples we have seen, movement is overt, with phonetically visible effects. It has been assumed widely that certain elements may move covertly as derivations enter LF, producing no phonetic effect. Examples include sentences containing quantifiers such as everyone, some student, most people. Chomsky (1976) argued that quantifiers are located covertly on the (left) periphery of the clause containing them, binding a variable in their surface position. Thus the surface sentence John hates every politician has the predicate– calculus style of representation For e ery x, x a politician, John hates x. May (1977) suggested that this representation may be obtained by an instance of Move α that raises the quantifier leftward, in a style reminiscent of ‘quantifier lowering’ rules proposed by generative semanticists in the early 1970s. Important arguments include generalizations concerning the possibilities of interpreting pronouns as ‘bound variables’ (Higginbotham 1980).

Another sort of covert movement is that of Whphrases in languages in which they occur typically in their ‘original’ positions. Unlike English-type languages, Chinese (and many other languages) leave their question words in situ when forming Whquestions. Thus What did you buy? in English is simply ni mai-le shenme ‘you bought what’ in (Mandarin) Chinese. Note that the Chinese sentence (17) below is ambiguous between a direct and indirect question reading, corresponding to two distinct forms in English, as shown in sentence (18):

(17) ni jide Zhangsan mai-le shenme?

you remember Zhangsan bought what

(18) a. Whati did you remember that John bought ti? (direct question)

- You remembered whati John bought ti. (indirect question)

Despite the overt differences, Huang (1982) argued that the two languages (and all languages) have essentially the same LF representations. In particular, although Wh-phrases do not move overtly in Chinese, they do so covertly in LF. The ambiguity of sentence (17) follows as a result of the fact that shenme ‘what’ may be moved to the subordinate clause below jide ‘remember’ or to the main clause, deriving LF representations not unlike sentences (18a and b). In addition to capturing certain cross-linguistic generalizations, this hypothesis is supported by the fact that interpretation of in-situ Wh-questions is subject to some restrictions that govern overt movement, e.g., the ECP.

As an instance of Move α, LF movement is not limited to A -movement like quantifer-raising or Whmovement. Given the Wh-movement parameter (some languages move Wh-phrases overtly, others do it in LF), proposals exist in the current literature that both A-movement (e.g., object shift) and head-movement (e.g., V-to-I or N-to-D raising) may occur overtly in some languages but covertly in others.

6. Current Issues And Future Prospects

Recent and current works in the Minimalist Program have been guided by the desire to limit theoretical apparatus to a minimum and assume only rules that apply ‘least effort’ and as a ‘last resort.’ The last requirement has led scholars to require that no rule, not excepting Move α, can apply optionally. Each operation must be forced (or ‘triggered’) by grammatical elements that need to be ‘checked off’ or which would otherwise cause a derivation to ‘crash.’ Under the idea of ‘triggering,’ Move α is reformulated in Chomsky (1995) as a general rule of ‘attraction’ by the triggering element (Attract F). Considerations of economy favor the assumption that while overt movement unavoidably involves whole words or phrases, covert movement may simply move features. The overt–covert parameter continues to play an important role in accounting for cross-linguistic variation, now seen as a function of the variation in the nature of the triggers (the ‘attractors’) across languages.

The postulation of movement in syntactic theory has proven a productive probe into the inner workings of the human language faculty. Many discoveries have been made and questions answered since Affix Hopping came into being. The idea of ‘covert movement’ in LF opened up new possibilities and raised new questions. In current Minimalist inquires, ever more emphasis is given to the role of movement, with new consequences that will continue to intrigue future researchers.

Bibliography:

- Chomsky N 1955 The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory. Harvard University and MIT Press, Cambridge, MA; published in part in 1975 by Plenum Press, New York

- Chomsky N 1964 Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Mouton, The Hague, The Netherlands

- Chomsky N 1965 Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Chomsky N 1973 Conditions on transformations. In: Anderson S R, Kiparsky P (eds.) A Festschrift for Morris Halle. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, New York

- Chomsky N 1975 Reflections on Language. Pantheon Books, New York

- Chomsky N 1976 Essays on Form and Interpretation. Elsevier, Amsterdam

- Chomsky N 1981 Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris Publications, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

- Chomsky N 1986 Barriers. MIT Press, Cambridge, The Netherlands, MA

- Chomsky N 1995 The Minimalist Program. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Higginbotham J 1982 Pronouns and bound variables. Linguistic Inquiry 11: 679–708

- Huang C-T J 1982 Logical Relations in Chinese and the Theory of Grammar. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA; published 1998 by Garland Publishing, New York

- Huang C-T J 1994 Logical form. In: Webelhuth Q (ed.) Handbook of Government and Binding Theory and the Minimalist Program. Blackwell, New York

- Kayne R 1981 ECP extensions. Linguistic Inquiry 12: 93–133

- May R C 1977/1990 The Grammar of Quantification. Ph.D. dissertation, Garland, New York

- Rizzi L 1990 Relativized Minimality. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Ross J R 1967 Constraints on variables in syntax. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA; published as Infinite Syntax 1986 by Ablex, Norwood, NJ