Sample Linguistic Aspects of Conversation Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Conversations are social creations. They are produced one step at a time as people carry out certain joint activities. A joint activity is one in which two or more people have to coordinate with each other to succeed (Clark 1996). These include not only waltzing, playing a piano duet, playing tennis, but gossiping, planning a party, and negotiating a contract. In waltzing, duets, and tennis, people coordinate moment by moment by means of gesture, touch, and other actions; but in gossip, planning, and negotiation, they use speech as well—they converse. What people do and say is not determined beforehand. It emerges as they negotiate their way through these activities.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Conversations reflect the joint activities they co-ordinate. Every joint activity has participants—the people actually taking part, who are distinct from non-participants (bystanders, onlookers, over-hearers)— and so do the conversations that emerge from them. The participants take particular roles, such as doctor and patient, teacher and student, or friend calling and friend called, and the roles constrain what the participants do and say. Every joint activity has public goals—mutually agreed-upon purposes for carrying them out. The overall goal may be to exchange gossip, plan an outing, or negotiate a contract, and these have subgoals. Although some of these goals are set from the start, most get established as the participants go along. The participants also have private goals—to be polite, not to lose face, or to finish quickly, for example—and these, too, constrain what the participants do and say. Finally, people often engage in two or more joint activities at a time—such as gossiping and eating dinner together—so their conversation switches back and forth between them.

Working together in a joint activity takes commitments and actions by all the participants. Joint activities have boundaries—distinct beginnings and ends, and transitions from one part to the next—but these boundaries don’t exist until the participants agree to them. To enter a planning session, for example, two people must agree on (a) what the joint activity is to be, (b) who is to take part, (c) in what roles, (d) at what time and (e) at what place, and (f ) whether or not they are each committed to taking part. They must reach these agreements at each transition point as well. What is remarkable is that people accomplish all this locally, turn by turn (Sacks et al. 1974).

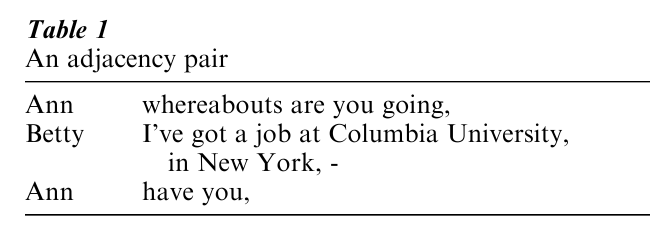

One basic unit of conversation is the adjacency pair (Schegloff and Sacks 1973), as in the spontaneous example shown in Table 1 (all examples are from Svartvik and Quirk 1980).

Adjacency pairs each have two parts, by different speakers, where part 2 is conditionally relevant given part 1. Part 1 is a proposal, and part 2 is expected to be the uptake of that proposal. In Table 1, Ann proposes that Betty tell her whereabouts she is going, and Betty takes up the proposal by saying that she’s got a job at Columbia University. In just two turns, Ann and Betty manage to coordinate on the content, participants, roles, time, place, and commitments of their joint action. They would have failed if Betty had replied ‘What do you mean?’ or ‘You mean me?’ or ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I won’t tell you.’

Adjacency pairs are available for a wide range of joint actions. These include not only requests for

information (as in Ann and Betty’s exchange), but greetings (‘Hi,’ ‘Hi’), farewells (‘Bye,’ ‘Bye’), offers (‘Have some cake,’ ‘Thanks’), orders (‘Sit down,’ ‘Yes, sir’), and apologies (‘Sorry,’ ‘Oh, that’s okay’) (Stenstrom 1994). They are used for even the simplest exchanges of information (‘I’ve got a job … ’ ‘Have you?’).

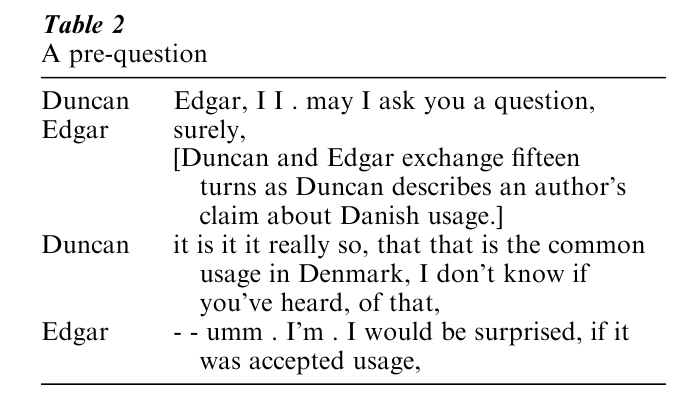

Adjacency pairs take only two turns, but they can be used to project larger sections, as in Table 2 (the disfluencies are in the original).

Duncan’s first turn is a pre-question (Schegloff 1980). With it he proposes to ask Edgar a question, and Edgar agrees. Duncan now has the freedom to take up preliminaries to his question, and it takes the two of them fifteen turns to do that. Only then does he ask his question, and Edgar answers it. Pre-questions project not only the eventual question, but preliminaries to that question.

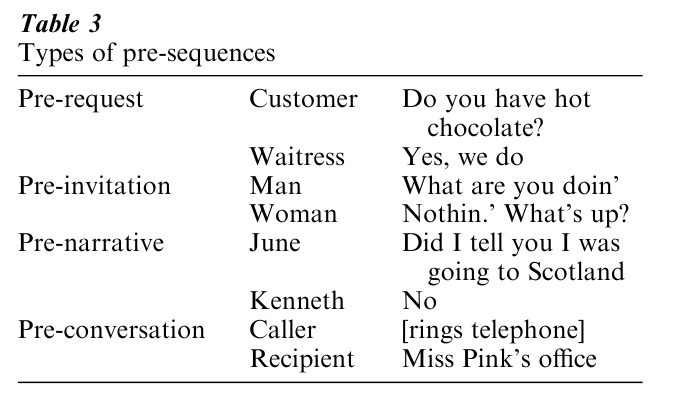

Pre-questions and their responses are one of a large family of so-called pre-sequences. Table 3 gives a few more examples.

Each pre-sequence prepares the way for another joint action. The pre-request sets up a request (‘I’ll have one’); the pre-invitation sets up an invitation (‘Would you like … ’); the pre-narrative sets up a narrative; and the pre-conversation sets up an entire telephone conversation. So pre-sequences are useful in organizing longer sections of conversation.

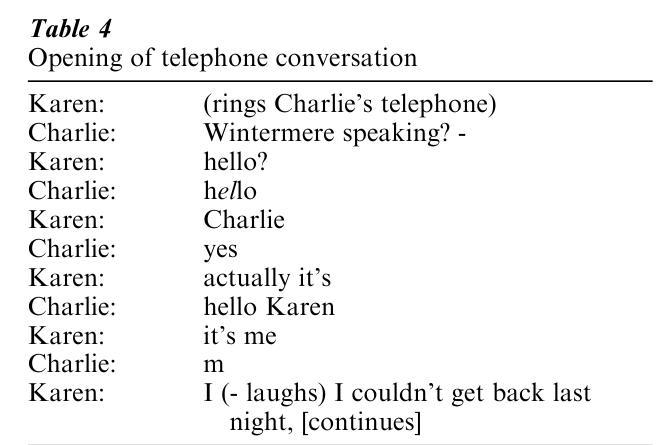

Opening a conversation takes special coordination as two or more people move from not being in a conversation to being in one. Table 4 gives the opening of a telephone conversation between acquaintances.

First, Karen and Charlie coordinate contact through a proposal to have a conversation (the telephone ring) and its uptake (‘Wintermere speaking?’). Next, they mutually establish their identities. Karen tells Charlie that she recognizes him in line 5, but Karen has to say ‘hello?’ ‘Charlie,’ and ‘actually it’s’ before he identifies her in line 8. Only then does Karen introduce the first topic. It took ten turns for them to coordinate on the participants, roles, time, place, and commitment to the conversation.

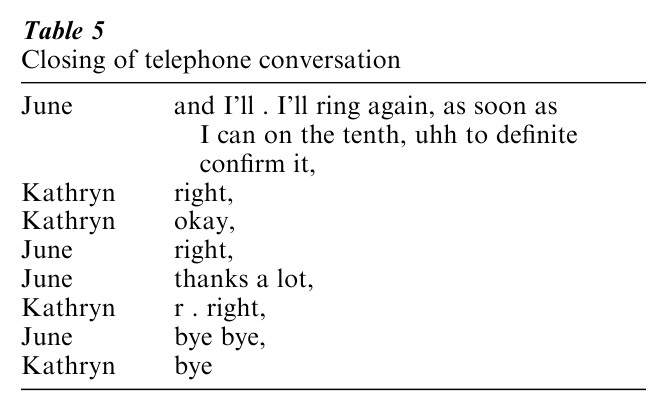

Closing conversations is no easier (Schegloff and Sacks 1973), as illustrated in Table 5 (an ending to a telephone conversation).

Although June and Kathryn finish a topic in lines 1 and 2, they cannot hang up without agreeing to hang up. So in line 3, Kathryn proposes to close the conversation (‘Okay’), and although June could now introduce a new topic in line 4, she agrees to Kathryn’s proposal (‘Right’). That opens up the closing in which the two exchange thanks (‘Thanks a lot’ ‘Right’) and then goodbyes. The two must agree to close the conversation before they can actually close it.

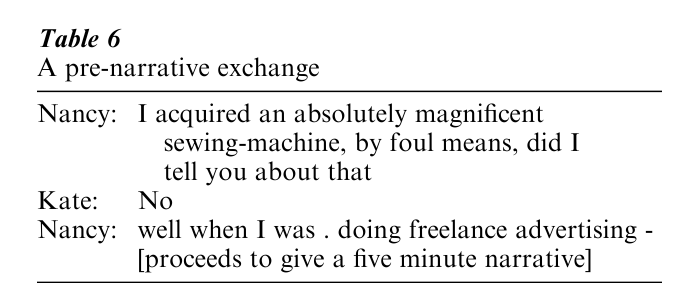

Conversations are opportunistic: The paths people take depend on the opportunities that become avail-able with each agreement. Consider the pre-narrative and its response in Table 6.

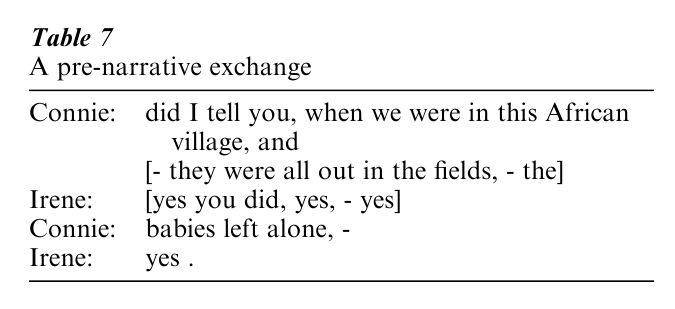

Nancy proposes to tell Kate a story (‘Did I tell you about that’), and Kate accepts (‘No’). But partners can also decline, as in Table 7.

Irene interrupts Connie (the speech in brackets is overlapping) to say that she has heard the story, and the two of them then go down a different path. Nancy and Connie used their pre-narratives to discover how best to proceed and, receiving different replies, took different routes.

People help signal which opportunities they are taking by using discourse markers (Schiffrin 1987). For example, Nancy used ‘well’ to signal that she was introducing a change in perspective as she began her story. Other discourse markers indicate such boundaries as the start of a new topic (e.g., ‘so,’ ‘then,’ ‘speaking of that’), the start of a digression (‘incidentally,’ ‘by the way’), or the return from a digression (‘anyway,’ ‘so’). All of these help in coordinating on what is happening next.

People carry out joint activities against their common ground—their mutual knowledge, mutual beliefs, and mutual assumptions. They infer their common ground from past conversation, joint perceptual experiences, and joint membership in cultural com-munities. When Ann asked Betty ‘Whereabouts are you going?’ she presupposed certain common ground—for example, that Betty has been looking for a university job in America, and that Ann doesn’t know where. Ann also adds to their common ground that she wants to know. Conversations proceed by orderly increments to the participants’ current common ground.

Conversations cannot succeed, therefore, unless the participants ground what they say. To ground what is said is to establish the mutual belief that the addressees have understood the speakers well enough for current purposes (Clark and Schaefer 1989). One technique for grounding is the adjacency pair itself. When Betty said ‘I’ve got a job at Columbia University,’ she displayed to Ann how she had interpreted her question. If Ann hadn’t been satisfied with that interpretation, she could have corrected it, e.g., by replying

‘No, I meant … ’ (Schegloff et al. 1977). In fact, she followed up Betty’s reply with ‘have you,’ displaying to Betty that she accepted her interpretation. Another technique is the back-channel response, acknowledgment, or continuer (Schegloff 1982). In two-party conversations, addressees are expected to add ‘uh huh’ or ‘mhm’ or ‘yeah’ at or near the ends of certain phrases. With these, they assert that they have under-stood the speaker so far and imply that the speaker should continue.

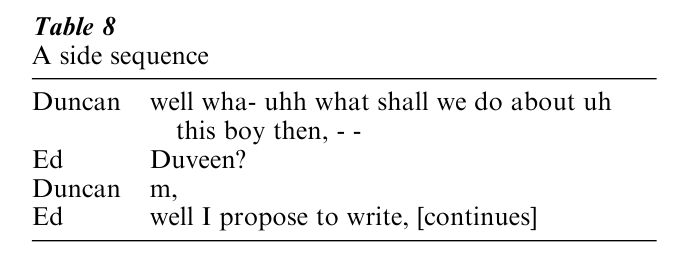

Grounding is sometimes achieved through side sequences (Jefferson 1972), as illustrated in Table 8.

When Ed didn’t understand to whom Duncan was referring as ‘this boy,’ he initiated an embedded adjacency pair, a side sequence, to clear up the problem. Only when he had cleared it up did he answer Duncan’s original question. Side sequences are initiated to clear up not only mishearings and misunderstandings, but also other pre-conditions to taking up the first part (e.g., ‘Why do you want to know?’). Grounding is also accomplished sometimes by overlapping speech. When Irene interrupted Connie’s offer ‘Did I tell you … ’ to say, ‘yes you did, yes, yes,’ she was signaling to Connie that she already understood and Connie didn’t need to go on.

The structure of conversations, in summary, is not determined from the outset. It emerges step by step as people coordinate on each new move in joint activities. People have to coordinate on the content, participants, roles, time, place, and commitment to each joint action, and they do that in a sequence of local, opportunistic agreements. It is these techniques that lead conversations to have the structure they do.

Bibliography:

- Clark H H 1996 Using Language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Clark H H, Schaefer E R 1989 Contributing to discourse. Cognitive Science 13: 259–94

- Jeffeson G 1972 Side sequences. In: Sadrow D (ed.) Studies in Social Interaction. Free Press, New York, pp. 294–338

- Sacks H, Schegloff E A, Jefferson G 1974 A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking in conversation. Language 50: 696–735

- Schegloff E A 1968 Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist 70(4): 1075–95

- Schegloff E A 1979 Identification and recognition in telephone conversational openings. In: Psathas G (ed.) Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology. Irvington, New York, pp. 23–78

- Schegloff E A 1980 Preliminaries to preliminaries: ‘Can I ask you a question?’ Sociological Inquiry 50: 104–52

- Schegloff E A 1982 Discourse as an interactional achievement: Some uses of ‘uh huh’ and other things that come between sentences. In: Tannen D (ed.) Analyzing Discourse: Text and Talk. Georgetown University Roundtable on Languages and Linguistics 1981. Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC, pp. 71–93

- Schegloff E A, Jefferson G, Sacks H 1977 The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language 53: 361–82

- Schegloff E A, Sacks H 1973 Opening up closings. Semiotica 8: 289–327

- Schiffrin D 1987 Discourse Markers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Stenstrom A-B 1994 An Introduction to Spoken Interaction. Longman, London

- Svartvik J, Quirk R (eds.) 1980 A Corpus of English Conversation. Gleerup, Lund, Sweden